Update on the “Eight Young Leftists” persecuted by Guangzhou police last winter, analysis of their case, and translation of Huang Liping’s open letter.

—

On November 15th of last year, police from the Xiaoguwei Subdistrict of Guangzhou stormed into a reading group at the Guangdong University of Technology, seizing six of its participants. Two of them, Zhang Yunfan and Ye Jianke, were held at the Panyu District Detention Center for a month as suspects for the crime of “gathering crowds to disrupt social order” (聚众扰乱社会秩序罪), along with two other people involved in the reading group, who were later seized at their residences: Zheng Yongming (on December 5th) and Sun Tingting (on December 8th). After prominent intellectuals circulated a petition, all four detainees were released on bail awaiting trial. Four other members of the reading group (Huang Liping, Xu Zhongliang, Han Peng and Gu Jiayue) went into hiding when their names appeared on a police wanted list. Still other participants were repeatedly harassed by police and university authorities, and some of the students involved had their scholarships revoked.

In January, we published translations of open letters by three of these “Eight Young Leftists” (左翼八青年),[1] as they became known in the campaign supporting them in mainland China and Hong Kong: Zhang Yunfan, Sun Tingting and Zheng Yongming. International news media picked up the story, and the campaign spread to other languages. Eventually the police seemed to have given up on the case, but the situation was not clear, so we hesitated to follow up. Then, a couple weeks ago, one of our readers sent us a translation of another open letter—the one by Huang Liping, published below. We take this opportunity to also update readers about what has happened since January and attempt an explanation of its significance. Most of what follows is drawn from the Eight’s own account of events through mid-March, published on the website “Epoch Pioneer” (时代先锋). They use their real names on the website, so discussing this openly seems consistent with their intentions.

Our impression is that the Eight Young Leftists—like the Feminist Five—are now using the media attention in response to their arrests both as insurance against future persecution and as a springboard for publicizing their political views and activities. Once again, the state’s machinations seem to have backfired.[2]

Last Winter’s Events

Throughout multiple interrogations and statements mentioned in the Eight’s open letters, the police seem to have focused the case on their suspicion that the reading group was receiving funds from abroad, which would have violated China’s new foreign NGO law, and they seem to have essentially dropped the case when it finally became clear that no evidence existed to support this claim. As Zheng noted in his letter:

If there really were “foreign powers” or “overseas labor unions” backing us somehow, the Xiaoguwei police would have already raised a big stink about this, and I would probably have never been released. In fact, the police repeatedly asked me questions about money—“who gave you money?”—but they quickly discovered that the reading group’s expenses amounted to only a few hundred yuan for printing. I’m quite poor, and no amount of searching could uncover any evidence to support the allegation that I received financial support from anyone.

Perhaps this is why the police originally charged them with “illegal business operations” (非法经营罪) and then changed it to “gathering crowds to disrupt social order” when no evidence of money was immediately forthcoming. The latter charge has become the default excuse whenever police want to hold basically any kind of suspected dissident[3] in detention long enough to find evidence with which to build a case, at which point the police then change the charge to suit the evidence. According to the Eight’s account from three months later, the police never managed to come up with evidence of anything other than the completely legal activities to which they had admitted from the start: the reading group’s discussion of sensitive topics such as recent labor struggles and the 1989 (“Tian’anmen” or “June 4th”) Movement, and the participants’ organization of “cultural” activities with university workers, such as dancing in the plaza with campus cleaning staff.

After a month at the detention center, the first two detainees (Zhang and Ye) were transferred to monitored residences and put under house arrest (指定居所监视居住), Zhang being “locked up in a secret location.” On December 21, the petition initiated by prominent intellectuals[4] (the Eight’s account highlights Qian Liqun, Kong Qingdong and Yu Jianrong[5] among the many who initially signed) was published online. Despite the petition and the platforms hosting it being repeatedly removed or blocked by China’s internet police, it was widely reposted with more signatures added. By January, the petition had accumulated over four hundred signatures, mostly from academics who risked endangering their careers. Apparently the petition mentioned only Zhang Yunfan because his case was the only one known to the public at that point.

On December 26th, the first English report on the case appeared in international media. Although Zhang and Ye had been sentenced to six months under house arrest, they were released after only fourteen days, likely in response to the petition and media coverage. On January 4th, Zheng Yongming and Sun Tingting were also released from the detention center on bail awaiting trial.

On January 15th-17th, Zhang, Sun and Zheng each published their open letters revealing that the case involved more than just Zhang. Sun’s letter in particular detailed the extent to which the state violated its own regulations along with the basic dignity of the “suspects.” These and subsequent letters by the other five also clarified their political motivations and refusal to surrender, their courage reinforced as they learned of the petition, the media coverage and Zhang’s initial open letter.

Three days later, two of the four young leftists in hiding published their own open letters: Huang Liping (translated below) and Xu Zhongliang. The same day, a group of elderly Maoists in Xi’an organized a street demonstration where they displayed banners reading “Resist the Panyu police arrest and repression of young people and students studying and promoting Marxism-Leninism-Maoism,” signed “The Masses of Shaanxi.”[6]

January 20th protest supporting the Eight in Xi’an

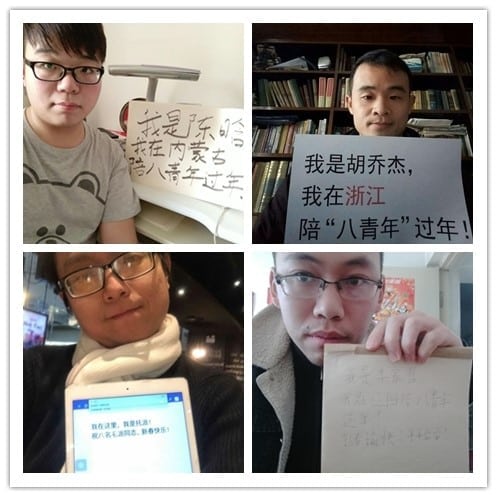

The next day, a sixth open letter was published (by Han Peng, another of those in hiding), and the broad-left network Left 21 organized demonstrations in Hong Kong, initiating their own petition. An international photo campaign was also launched, in which public figures took pictures of themselves with signs supporting the Eight.

On January 22nd, Zhang Yunfan appeared in Beijing at a public memorial service for Han Xiya (1923-2018), where Zhang read a poem he had written in honor of this “old revolutionary and labor leader.”

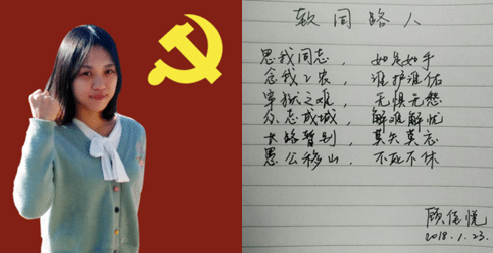

The following day, a seventh open letter was published by Gu Jiayue, the last of the four in hiding.

Gu and her poem, “Dear Fellow Travelers”

The same day, Guangzhou police traveled out of their jurisdiction to Sun Tingting’s parents’ home in Jiangsu, where she was recovering from her traumatic experience in the detention center. The police told her she had to go and check in at the local police station every morning at ten o’clock until her trial.

On the 24th, the Guangzhou police again traveled out of their jurisdiction to Beijing, where they interrogated Zhang for two hours. The same day, another Chinese petition appeared, this one signed by thirty-six “prominent left-wing figures” proposing the formation of a “Concern Group for the Eight Youth” (八青年关注团), and recommending that the Eight meet with the Ministry of Public Security (MPS) in Beijing and “explain the situation.” By February 6th, nearly 1500 people had signed the petition, and the Concern Group presented it to the MPS along with other materials relevant to the case.

“Join the Concern Group for the Eight Youth, stand up for justice!”

The next day, Ye Jianke published his open letter, the last of the eight. There he recounts that during his detention the police had asked him to “work for the government” and warned that, in the future, he had to inform them any time he planned to do anything related to “studying Marxism or Mao Zedong Thought.”

On January 29th and the following days, three students from Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine (Ji Chaochao, Hu Jianxin and Jin Shuai) were emboldened by the Eight and their supporters to speak out about their own experience the previous summer: Nanjing police had similarly stormed into the reading group of their left-wing student group Zhiyuanshe (致远社 — “Reaching Beyond”). In this case, the police had physically assaulting them during an all-night interrogation and threatened them with expulsion from the university.

In early February, nine police (six local and three from Guangzhou) went to the home of Xu Zhongliang’s parents in Henan, threatening grave consequences if their son did not immediately turn himself in. Three days later, a representative from the Concern Group visited Xu’s parents to comfort them and convey that their son had widespread support. A week later, three other supporters managed to “break through local police roadblocks” (突破当地警方阻碍) and visit Xu’s parents, offering them solace in the upcoming Chinese New Year without their son.[7]

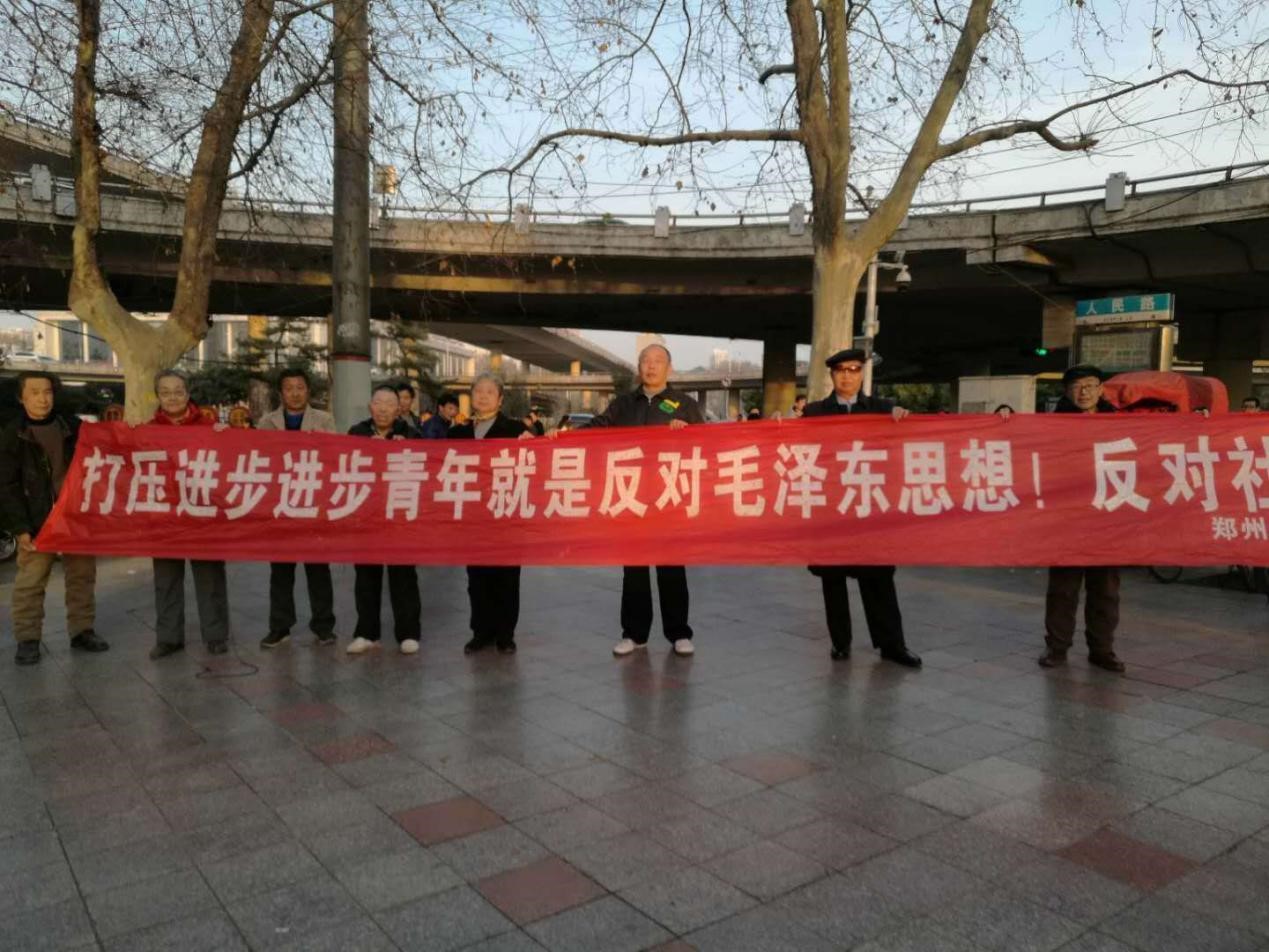

Meanwhile in Zhengzhou, a “Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Group” (毛泽东思想宣传队) held a demonstration supporting the Eight on February 3rd. Police showed up, confiscated their banners and said that, in the future, it was prohibited to display banners, make speeches or “record videos for uploading to the internet.” Nevertheless, the group returned, “braving the cold winds of China’s Central Plain” to hold further demonstrations on the 11th, 19th and 24th, and again on March 14th, each time being shooed away by the police but not arrested.[8] Throughout February, similar but smaller demonstrations also took place in several other cities, such as Lanzhou.

“To suppress progressive young people is to oppose Mao Zedong Thought!” — from one of the protests in Zhengzhou

“Big character posters” from the protests in Zhengzhou

On February 5th, Sun Tingting posted a message on Weibo seeking legal counsel, and soon two lawyers volunteered to represent the Eight. A few days later, the Concern Group launched a fundraiser to help cover the following costs: (1) living expenses of the Eight and their families, since many of them were unable to work during this time; (2) living expenses of the students whose scholarships had been revoked; and (3) “fees for legal procedures they may face in the future.” By the end of the month, nearly 500 individuals and groups had donated a total of 266,676 yuan.[9]

In mid-February, the Epoch Pioneer website launched a call to “accompany the Eight Youth through the New Year,” and readers submitted poems, voice recordings and photos of themselves with messages of encouragement. On Chinese New Year’s Day, Zhang, Sun and Zheng published videos of themselves thanking everyone for their support, and the four still in hiding somehow managed to have their written greetings published without revealing their whereabouts.

New Year’s greetings supporting the Eight

Two weeks later, Sun published a statement titled “Please Stop Harassing My Family,” revealing that the police in her Jiangsu township had continued to threaten her parents. They said that if she did not go and check in at the station within three days, Sun would be “locked up for life.” The letter defiantly replied that she was in Beijing, “so come and get me!”

On March 3rd, Zheng published a statement with the same title, revealing that while he had been looking for work in Beijing, Guangzhou police had seized his brother in the middle of the night, taken him into the station and threatened him.

All Eight of the young leftists finally made their first public appearance together on March 13th, when several prominent figures from the Concern Group (including Yang Tie, Wang Zhaohui and the famous writer Huang Jisu[10]) “turned them in” to the MPS along with another stack of materials related to the case. An MPS official confirmed that the four suspects who had been in hiding were no longer on a wanted list, and promised to ensure that the Guangzhou police would conclude the case “in accordance with the law.”

As for the other four, it seems they will remain registered as “suspects” until a year has passed since the days of their arrests, at which point the charges will officially be dropped if the police cannot find sufficient evidence to present a case against them in court. (This is also what ended up happening with the Feminist Five in 2016.)

Making Sense of It All

Our guess regarding the original impetus for the arrests is that the local police had hoped to obtain some political credit and assumed that this reading group would be an easy target. They knew the national leadership was rewarding local forces that somehow contributed to its mission of raising the party-state’s “governing capacity” (执政能力) in the face of economic slowdown—a growing threat to the CCP’s legitimacy. This mission includes ridding the social sphere of any impure ideological elements, especially those that could somehow be linked to “foreign powers” (境外势力) and independent organizations promoting “rights defense” (维权) for segments of the population excluded from “the Chinese dream.”

University students have long been a special focus of state anxiety, considering the prominent role they’ve played in broader, sometimes subversive movements throughout modern Chinese history. The Eight’s attempt to establish bonds between students and campus workers, even in such an innocuous form as dancing together in the plaza, seems especially likely to have raised “red flags” in the eyes of both university authorities and the Xiaoguwei police, since the only recent industrial dispute in which Chinese students have gotten directly involved just happened to take place in the same subdistrict three years prior: the sanitation workers’ strike of 2014.

It also seems likely the police knew that their Nanjing counterparts had gotten away with a similar sting operation last summer and probably been rewarded in some way, even though it did not progress to the level of a court case. (And who knows how many similar cases have gone unreported?) A crucial difference, however, was that Zhang Yunfan had connections inside China’s generally patriotic but not unprincipled network of “public intellectuals.” Because of this, news was able to spread and generate enough bad press about such blatant hypocrisy that someone at the MPS decided they had to put an end to it. Not the first time for Guangzhou police to tread in their own shit.

Activities since February

So instead of scaring the Eight into trading their “socialist values” for mainstream lifestyles centered on making money, reproducing their labor-power and minding their own business, these harrowing experiences of state persecution actually ended up adding fuel to the young Maoists’ will to fight for a better world, now galvanized by the knowledge that others are willing to stand up for them. In addition to continuing to publish writings about sensitive issues under their individual names, they have also started to use the collective label “Eight Youth” as a sort of brand to direct attention towards the struggles of others. In late March, for example, they travelled to Shanghai to support a sanitation workers’ strike. They wrote a detailed report and published it under their collective name, explaining:

We are the “Eight Young Leftists” (左翼“八青年”) who were arrested and forced into hiding. Our charges have not yet been dropped and our families are often harassed [by the police], but no matter how many tribulations lie ahead, we will never give up “giving voice to the class without a voice.” When the sanitation workers went on strike, we immediately traveled to Changning in Shanghai to bear witness to their struggle for survival.

Photo from the Eight’s visit to the sanitation workers’ strike in Shanghai

Earlier that month, three days after the Eight appeared together at the MPS, an environmental activist named Lei Ping[11] was arrested in Maoming, Guangdong for “spreading rumors and disrupting public order” in her efforts to expose a case of industrial water pollution. The Eight published collective greetings highlighting the commonality of their cases, saying:

Your early release from detention was due not to the good graces of the police, but to actions of solidarity by those who fight for justice…. More and more social incidents like this demonstrate that it is only by combining all of our forces and fighting together that we can achieve a just society.[12]

The first use of this collective label to support other victims of state persecution was Gu Jiayue’s letter to the prominent left-feminist “Datu” (Zheng Churan)[13] in response to the Women’s Day deletion of the Weibo and WeChat accounts for Feminist Voices (女权之声)—probably the most popular feminist platform in China, with 180,000 followers on Weibo. Although Gu signed this letter individually, she titled it “Dear Datu, the Leftist Youth Stand Shoulder to Shoulder With You,” opening it with the Eight’s collective relationship to Datu:

Not long ago, when we young Maoists were locked up or on the run, the feminist Datu resolutely lent the strength of her name to the petition. Today I’m finally able to say something on her behalf…. In this cold winter of idealism, all oppressors prosper and all the oppressed share the same blood. Our criminal charges were similar: “foreign powers,” “detained as criminal suspects,” “sabotaging China’s stability and harmony”! … We do have our differences from feminists such as Datu, but when dark clouds press down upon us and no one else dares to speak up, it makes no sense to be narrow-minded and debate about details.

Meanwhile, individuals from the group have continued to publish theoretical and historical texts, along with reports on international affairs and recent struggles in China they’ve investigated offline. These include several reports on a long-term labor dispute at a battery company whose factories they’ve visited in multiple cities, and interviews with a group of construction workers from Hunan who’ve been petitioning the Shenzhen Government for nine years, seeking to obtain treatment for silicosis they contracted on the job there.[14]

In short, state repression has not succeeded to silence the Eight Young Leftists – if anything, it has backfired, strengthening their will to fight and, more importantly, expanding and exercising networks of solidarity among young people and old who hold multiple political perspectives but share a common hostility to the status quo.[15] We can only hope that such activists’ commitment to militant investigations and “seeking truth from facts” will eventually direct their energy away from the dead religions of 20th century developmental regimes and toward a communist movement adequate to the specific capitalist conditions now in existence.

Below we publish our reader’s translation of Huang Liping’s open letter, penned while he was still hiding from the pigs in January.

“Let the People Themselves Decide Whether I’m Guilty”

by Huang Liping, January 20, 2018

Translated by Richard Chen

Huang Liping

I am one of the four young people who are in hiding because of the Zhang Yunfan reading group incident.

After graduation, I lived and worked in [Guangzhou’s] university district. Once, when I was jogging at the Guangdong University of Technology (GDUT), I met a group of middle-aged women (阿姨) dancing together with students in the plaza.

They reminded me of my mother – women workers at the bottom rungs of society.

They were from the countryside. Their work [as campus general staff] was hard, and they made meager wages.

It’s really that simple: I started dancing with them, playing games with them, and doing as much as I could to help them.

They lived packed in tiny rooms, more than ten people together in each. Some of those rooms even had couples living together in them. These women would have eagerly assimilated into society, but nobody even notices their existence. They joke that even the stray cats on campus are noticed more than they are. They’ve worked on campus many years now, but some of them have never even taken the subway.

For the sake of their children, they live this harsh life. Seeing them was like seeing my mother again, and the hard life she lived every day and night.

My mother worked in a sweatshop for many years. Whenever she dragged her dried-out, exhausted body back to the village, all she could remember was the name of the factory, and that the factory was in Guangdong. She did not even know that the brilliant, glamorous Shenzhen she saw on television was where she worked.

Every year, she would bring all of her savings and my new clothes home, pick me up, secretly wipe away her tears and say:

You must study hard. Don’t be like me, without any learning. I get pushed around at work, I’m always tired and I never earn enough, and everybody looks down on me…

The way she said these words is the same way these other women speak.

I’m sure you can understand why it is that I drifted in with them and wanted to help them. The other volunteers and I gradually grew to know each other and began to feel like we had the same goals.

The “fat boy” over there dancing with them was Zhang Yunfan, who was later imprisoned for forty-four days. The girl who was enthusiastically trying to maintain the rhythm was Gu Jiayue, who is now also in hiding.

I can say that they have been the best young people I’ve met in my life. I’m sure the women at GDUT would also say that they are wonderful people. One of them said:

This is the first time I’ve been dancing in my life. Normally only the families of professors get to dance, and you have to pay. You are wonderful students. You don’t think we’re stupid, and you patiently teach us.

If my mother had met such young people in the factory, even if her life was hard, she could have been a little happier!

If my father had met such young people, when he was doing construction work on tunnels, maybe he wouldn’t have had to leave work and go on strike.

So these women are like my mother, and Zhang Yunfan and the rest are like my brothers and sisters. As the old Maoist saying goes, the depth of your intimacy is decided by your class!

I regret that, because of conflicts with my work, I did not participate in the reading group. But if I could turn back time, I would have gone for sure!

Just because of intimidation from the Xiaoguwei police, I am not going to disown these women and my connections with these other students, or deny that I am a leftist, or that I believe in Mao Zedong!

Why were my mother and those women working at GDUT condemned to a life of hardship?

Some people say that they don’t work enough, and that you have to endure hardship in order to advance in society. Others say that’s just the way life is.

The people who say these things are either stupid or evil.

I was instinctively disgusted with the people who said these things, but had no way to refute them until I went to college. There, in the classes of my teacher Zeng Peng, I first found the key to understanding the world.

Marx’s Capital explained to me the meaning of surplus-value and exploitation. It explained to me why you can never become rich by selling your labor-power, and how capital devours the youth of all those who work.

And the Selected Works of Mao Zedong explained to me that the people are the motive force of history, that we should become the masters of our own house and fight for our own interests.

I have never worshipped Mao Zedong. It is reality and the conditions of the workers that forced me to believe.

It is because of discussing the miserable situation of working people and their struggle to defend their interests, and because of propagating Marxism and Mao Zedong Thought, that the reading group was labelled an “anti-CCP, anti-society organization,” and that Zhang Yunfan was detained.

What is ridiculous about this is that the police say not only that the reading group was subversive, but that dancing in the plaza had “ulterior motives.” But if the police say this was a “political activity” and that we were “organizing workers to defend their rights” – well, isn’t that an admission by the state that the workers’ rights had already been violated in the first place?

And now just because I helped organize these dances, I too have become a suspect of “secretly plotting the defense of rights” (密谋维权). With charges like that, of course I went into hiding!

Not only do the Xiaoguwei police not help the workers to defend their rights, but the moment they smell anything that actually seems like “defending worker’s rights,” they hunt it down and try to destroy it!

When I learned of the experiences of Zhang Yunfan and others over the past month, I became so angry, I couldn’t bear it anymore! Especially what happened to Sun Tingting, that would make anybody furious! It is completely clear that she, a woman who cares about the public welfare, who makes a meager salary, who, just because of her association with the reading group, had her door broken down by the Panyu Police, was dragged away by force and subjected to criminal detention, based on completely fabricated charges!

Xiaoguwei police, how can you claim to be “the People’s Police, Serving the People” with a straight face?

Well, since you are hunting me down, then I will announce to the world:

If believing in Mao Zedong Thought is “extreme ideology,” then yes, I have an “extreme ideology”!

If organizing campus workers to dance in the plaza is “disrupting social order,” then yes, I am indeed “disrupting social order”!

Let the people themselves decide whether I’m guilty!

I don’t care how long you imprison me or how you treat me. What is this little incident, compared to what the revolutionaries of the 20th century endured?

Chop off my head, I don’t care,

You’ll never slay the ideals I bear.

Even if you kill Xia Minghan[16] today,

The masses will still follow his way!

Whether it’s my past, present or future, I don’t believe that I am wrong. No matter how many police you have, how many charges you bring, or how many internet posts you censor, you will never blind the eyes of the people.

As Mao said, the Chinese people are not afraid of ghosts!

我是否有罪,人民自有公论

黄理平

我叫黄理平,是张云帆读书会事件中被网上追逃的四名青年之一。

毕业后,我在大学城工作生活,一次跑步到广工,遇见一群阿姨和学生在跳广场舞。

她们很像我的妈妈——显而易见的底层劳动妇女。

显而易见的来自农村、工作辛苦、工资微薄。

就这么简单,我开始和她们一起跳舞,做游戏,力所能及为她们服务。

她们常常十几个人挤在一个狭小的宿舍,有的宿舍甚至还住了好几对夫妻;

她们渴望融入这个学校,但是从来没有人意识到她们的存在,她们常常自嘲校园里的流浪猫都比她们的存在感高。

她们在广工工作好多年了,有的人却还从来没有坐过地铁。

她们为了孩子过得好点,自己过着苦行僧般的生活——我好像看到了我的妈妈,看到了她艰难的日日夜夜。

妈妈在血汗工厂工作多年,当她拖着被榨干的身体回到村里的时候,却只知道她的厂名,只知道厂子在广东。

她不知道电视上那个光鲜亮丽的深圳,就是自己工作的地方。

每年,她都会带着所有的收入和我的新衣服回家,抱起我偷偷抹眼泪:

“要好好读书啊,别像我一样,没文化,打工被人欺负,又累又挣不到钱,还被人看不起……”

——说话语气和这些广工的阿姨一模一样。

你一定能理解,为什么我漂泊在外,却仍旧执着地想为她们做事。我和服务她们的志愿者慢慢熟悉起来,感觉志同道合,相见恨晚。

那个扭着胖胖身子的男生,就是被监禁四十四天的张云帆;而那个很努力喊节拍的女生,就是同样被网上追逃的顾佳悦。

至今为止,我仍旧认为他们是最好的青年。我相信,那些广东工业大学的后勤阿姨,也一定会认为他们是最好最好的青年。

有个壮族阿姨腼腆地说:“我这辈子还是第一次跳舞,平常学校都是老师的家属在跳,要收钱,你们这些学生真好,不嫌我们笨,一遍一遍地教我们。”

如果妈妈在厂里的时候,能够遇到这样的青年,就算辛苦,也能够过得开心一点吧!

如果爸爸在修隧道的时候,能够遇到这样的青年,也不会为了讨回血汗钱,集体爬上隧道门洞吧?

所以,这些阿姨就像我的妈妈,张云帆他们就像我的兄弟姐妹——这也许就是老话说的,亲不亲阶级分吧!

很遗憾,由于工作时间冲突,我并没有参加过广工的读书会。

如果时间可以倒流,我会一定会参加的!

我才不会因为小谷围派出所的威慑,就和这些阿姨、这些青年撇清关系,就否认自己是左派,是毛泽东思想的信仰者!

我的妈妈,广东工业大学的后勤阿姨,为什么注定一生艰辛?

有人说,她们还不够努力。吃得苦中苦,方为人上人。

还有人说,这就是命。

——能说出这种话的人,不是蠢就是坏。

我本能地反感这些说辞,却又无力反驳。直到进入大学,在左鹏老师的一节公开课上,我才第一次找到认识世界的钥匙。

《资本论》告诉我,有剩余价值,有剥削,出卖劳动力不可能致富,资本会吞噬一切劳动者的青春;

《毛泽东选集》告诉我,人民是创造历史的动力,人民应该当家作主,捍卫自己的权利!

我从来没有毫无理由地崇拜毛泽东。是现实,是劳动人民的处境,让我不得不信。

而正是因为讨论劳动人民的悲惨境遇和维护权利的抗争,宣传马克思主义毛泽东思想,读书会就被定为“反党反社会”,张云帆也被拘留了。

最滑稽的是,警方不仅将读书会视如洪水猛兽;还觉得广场舞“别有用心”:组织阿姨跳舞是不是有“政治目的”,是不是密谋给工人维权?——这么说,警方也知道工人的合法权益被侵犯啦!

而我,作为广场舞积极分子,自然是“密谋维权”的嫌疑人。

当然要被网上追逃!

小谷围派出所不仅不帮助人民维护合法权益,反而一嗅到“维权”的气味就穷追不舍,欲置之于死地!

得知张云帆等青年一个多月来的遭遇,我更是怒不可遏!

特别是孙婷婷的遭遇,简直人神共愤!朗朗乾坤,昭昭日月,一个热心于公益事业,领着微薄薪水的女孩子,仅仅因为和读书会成员有所接触,竟然被番禺警方破门而入强行带走,然后“随便安个什么罪”“干脆”刑事拘留!

小谷围派出所,你们怎么对得起“人民警察为人民”?!

既然你们正在追逃我,那我在此大声宣布:

如果信仰毛泽东思想是“思想极端”,那我就是“思想极端”;

如果组织后勤阿姨跳广场舞是“扰乱社会秩序”,那我确实是“扰乱社会秩序”;

我是否真的有罪,人民群众自有公论。

至于我会被关多久,受到怎样的对待,都是无所谓的。这点事跟上世纪的理想主义者们比起来算什么呢?“砍头不要紧,只要主义真;杀了夏明翰,还有后来人!”

我过去、现在、将来,都不会觉得自己有错。

无论你小谷围抓多少人,定什么罪,删多少贴,都无法蒙住人民群众的眼睛!

毛主席说过:中国人民从来是不怕鬼、不信邪的!

2018年1月20日

Notes

[1] Some texts from the campaign drop the “Leftist” and just say “Eight Young People” (八青年), an anecdotal explanation being that at least one of the eight does not identify as a leftist. We decided to continue using “Leftist” in order to highlight the specific political nature of this case, in contrast with the much more widely publicized cases of state persecution against “liberals” (自由派)—usually categorized by themselves and others in China as “right-wing,” mainly because they take capitalism for granted as part of their various programs for liberal democracy, regardless of whether the liberals are more “neoliberal,” “social democratic” or “conservative.” (For more on the various political orientations active in China today, see the forthcoming second issue of the Chuang journal.) New Bloom’s article on these arrests makes the common mistake of conflating contemporary Chinese Maoism with nationalism (and thus assuming that Zhang Yunfan is a nationalist), overlooking the major divide between nationalist and internationalist Maoists, with the latter (known as “left-wing Maoists”) often siding with Trotskyists, for example, against “right-wing Maoists” and others in debates over issues such as China’s foreign policy.

[2] In addition to this and the Feminist Five case, a similar sort of backfiring seems to have occurred in response to the crackdown on labor NGOs in December 2015. We have met several mainland labor activists who first became interested in labor, and in at least one case Marxism (after a background in a liberal “civil society” student group), because of the campaign to support the activists arrested at that time. For a detailed analysis of the crackdown and its significance, see “Making Sense of the 2015 Crackdown on Labor NGOs in China” by Shannon Lee.

[3] One major exception is when the suspected dissidents are Muslim, in which case they are now usually charged with “terrorism.” (This too is addressed in the forthcoming second issue of the Chuang journal.)

[4] We follow the Chinese terminology in using the somewhat archaic category “intellectuals” because some of these figures are not academics but independent writers, for example. Some of them identify as “public intellectuals” (公共知识分子) because they hope to serve the public good by influencing state policy or participating in social movements, in addition to purely academic work.

[5] It is worth noting that it was not only leftist intellectuals who signed or even perhaps co-authored the petition. Yu Jianrong, for example, has long been widely categorized as a liberal (not sure how he identifies himself), although his research focuses on the collective actions and organization of “disadvantaged groups” such as ruralites fighting land grabs.

[6] At the same event, the protestors also condemned the demolition of a Mao statue in Luoning, Henan taking place at that time alongside the construction of Christian churches – a cause célèbre among many Maoists, giving rise to protests in multiple provinces.

[7] It is unclear whether the son came home to spend the New Year holiday with his parents. If so, he would have probably needed to sneak by the aforementioned police roadblocks.

[8] Our impression is that the police no longer consider these elderly Maoists a serious threat because of their growing age and dwindling numbers, so they simply confiscate their banners and send them home but never arrest anyone. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, however, such protests were linked to the massive movement of state enterprise workers fighting layoffs, with demonstrations regularly featuring tens of thousands of workers occupying factories and sometimes even kidnapping officials or throwing them from buildings. At that time, even small demonstrations in the park (calling for Mao’s birthday to be recognized as a national holiday, for example) were sometimes met with charges of “inciting the subversion of state power.” See “On December 24, 2004, Maoists in China Get Three Year Prison Sentences for Leafleting,” Monthly Review (2005).

[9] “关于社会各界人士给“广州读书会八青年”捐款情况的说明”.

[10] Huang Jisu is probably most well known authoring a play about Che Guevara and organizing events related to it in the late 1990s and early 2000s – a key moment in the emergence of the post-1989 left. See “Che Guevara: Notes On The Play, Its Production, and Reception” by Huang Jisu (translated by Xie Fang), in Debating the Socialist Legacy and Capitalist Globalization in China (edited by Xueping Zhong and Ban Wang), New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

[11] Lei Ping was already known to the public as “firefly girl” because of her previous appearance on national television exposing the firefly industry’s harmful effects on the species and the environment.

[12] While this may sound trite, this statement seems significant not only as an interesting use of the “Eight Youth” label, but also as the first case we know of Chinese leftists, or of activists primarily focused on labor struggles, expressing support for such environmental activists who face criminal charges, let alone asserting that their goals can be achieved only by “combining forces.”

[13] See our translation of Datu’s article “Should Wives Be Shared or Rationed?”

[14] A few texts from this silicosis case have been translated into English and published here.

[15] This is not to say that the arrests and even the campaign to support the Eight have not also functioned to increase the level of fear in Chinese society about the risks of participating in any sort of activism, or even small group discussions of sensitive topics. That has also been an effect of the 2015 crackdown on labor NGOs and the arrests of the Feminist Five, for example, even while the campaigns in response also encouraged and politicized some supporters. Overall we might say that the result has been polarizing, with some people becoming less likely to take risks and others becoming emboldened or even radicalized. It is unlikely the local police considered either of such results, instead merely hoping to benefit their careers by implementing national policy, without a clear understanding of how the specific method of implementation might backfire. Only in the case of the 2015 crackdown on labor NGOs was there evidence of central support for the arrests and effort to use them to spread fear: a series of reports in national news media slandering the prime suspect Zeng Feiyang and portraying the crackdown in a positive light. The arrest of the Feminist Five was coordinated among police departments in multiple provinces, so it may have been centrally initiated, but after the campaign to support the prisoners exploded into an international media spectacle and even became a diplomatic issue, central authorities seem to have backed off – perhaps a reason the case was dropped rather than going to court as planned. The persecution of the Eight, however, seems to have been locally initiated and at no point actively supported by central authorities.

[16] Xia Minghan (1900-1928) was an early leader of the CCP who was betrayed to the Kuomintang and executed. He wrote this poem while awaiting his execution.