This post is the third in a series of monthly summaries of highlights from Chinese-language news and social media, offering some analysis of economic trends and the changing character of class struggle in China. Through these posts, we hope to give English readers a broader sample of the discussions taking place across the linguistic and digital divide. In addition, we recommend a few recent English-language publications at the end. (If you notice mistakes or any important story that we missed, please contact as chuangcn@riseup.net and we can add it to next month’s post.)

Highlights from Chinese News and Social Media, February 2022

A Few Protests against the Russian Invasion of Ukraine Slip Past the Censors

As we write, Chinese government has yet to take a formal position on the conflict. The foreign ministry just announced that China and Russia are not “allies” but merely “strategic partners,” and state television aired a long interview with a Chinese student in Kyiv, who was allowed to express support for her Ukrainian friends. Meanwhile, social media platforms have been taking more active precautions by censoring multiple articles critical of the invasion or sympathetic with its victims in Ukraine. Below is a Twitter thread archiving such pieces as they’re censored:

And another with photos of one lonely protestor in a mainland city:

As we prepare to publish, we’ve just received a letter from a group of readers in China who wish to express their solidarity with the people of Ukraine and anti-war protestors in Russia, along with enmity for the ruling classes of all countries—a letter they feel cannot be published on mainland platforms. The letter may now be read here.

Fury & Repression Surrounding the Chained Woman of Xuzhou

News, independent investigation and state repression surrounding “the chained woman of Xuzhou” has sparked a wide-ranging discussion and a series of ongoing grassroots actions on- and off-line throughout China that threatened to overshadow the Olympics. Some observers feel this has become the most important moment in post-socialist Chinese feminism to date, drawing in a much wider section of the population than #MeToo or the events surrounding the Feminist Five from 2015 to 2019, with the chained woman becoming a symbol for women’s oppression more generally, and the role of the state and the market in modern forms of patriarchy. We hope to address this separately in future writings, but for now we direct readers to a few details:

Over the course of five statements (通报) released by the state, journalists and netizens have posed countless questions about discrepancies among the statements: What is the chained woman’s real name? Was she subject to human trafficking? Was she really the Lisu woman identified by local governments? Why did she lose most of her teeth? What is the government trying to cover up with these contradictory statements? Even after the latest announcement addressed some of these questions, doubts remain widespread, as in this example pointing out the logical inconsistency within almost every official conclusion.

Some observers have tried to take action in real life. Two women known by their Weibo usernames Wuyi and Quanquan—neither being journalists, and both apparently unconnected to existing feminist or other activist networks—went to Feng County (in Xuzhou Prefecture, Jiangsu Province) where the chained woman lived, hoping to meet her and offer support. They tried to visit her in the mental hospital where she was being held, but were turned away, even when one of them said she was sick and needed to see a doctor herself. The hospital took the flowers they had brought for the woman, which later appeared by the woman’s bed in a Central Chinese Television report, which repeated the official line and did not mention the visitors:

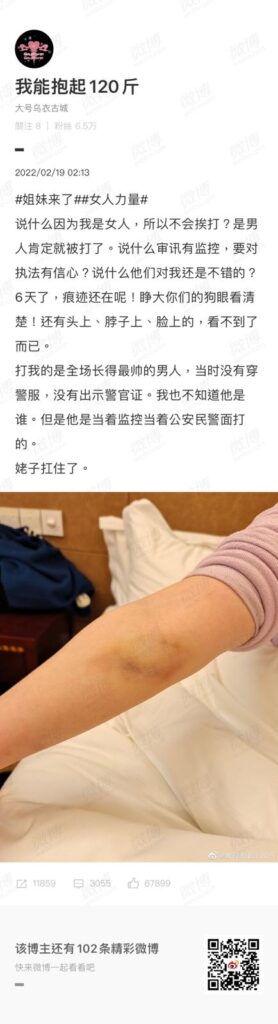

Outside the hospital, a man approached Wuyi and used force to take her phone away, and when she went to the police station to report this, she was placed under criminal detention as a suspect of the crime “picking quarrels” (the default charge for all kinds of activists and “unstable elements” in China). Quanquan was separately detained with the same charge, and both were held and questioned for several days before being released. Wuyi told the police that she would write down everything that happened and publish it as a book, to which they responded, “Just make sure it has a happy ending.” She posted a few pages of details on Weibo before the platform blocked her from further posts. The posts are archived here. Below is a screenshot of bruising from Wuyi’s handling by the police.

Meanwhile, the village in Feng County where the chained woman lived had been barred from entry in the name of pandemic quarantine, and journalists were turned away even after submitting all the requested documents. (This post’s header image above is a photo one of these journalists took at the entrance to the village where he was turned away, from here.)

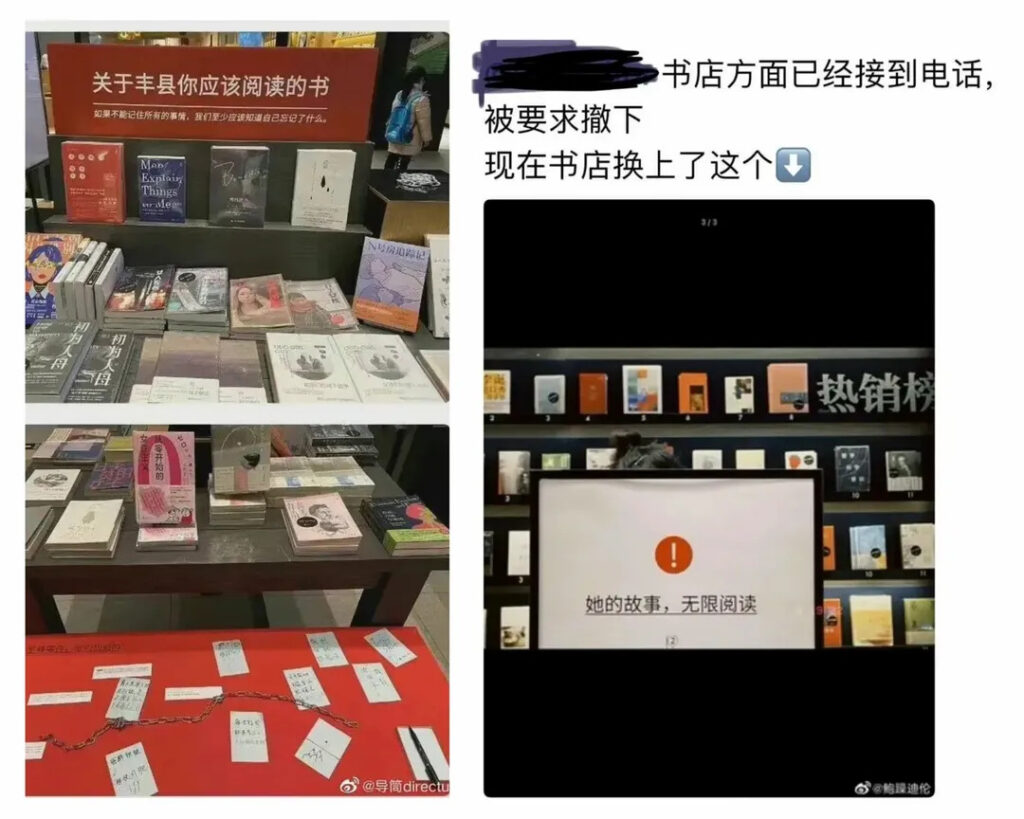

Elsewhere, bookshops throughout China set up displays about feminism and human trafficking, with signs such as “Books You Should Read about Feng County.” Police made them take down any reference to the chained woman, so instead some shops put up the symbol used on WeChat when a page is censored.

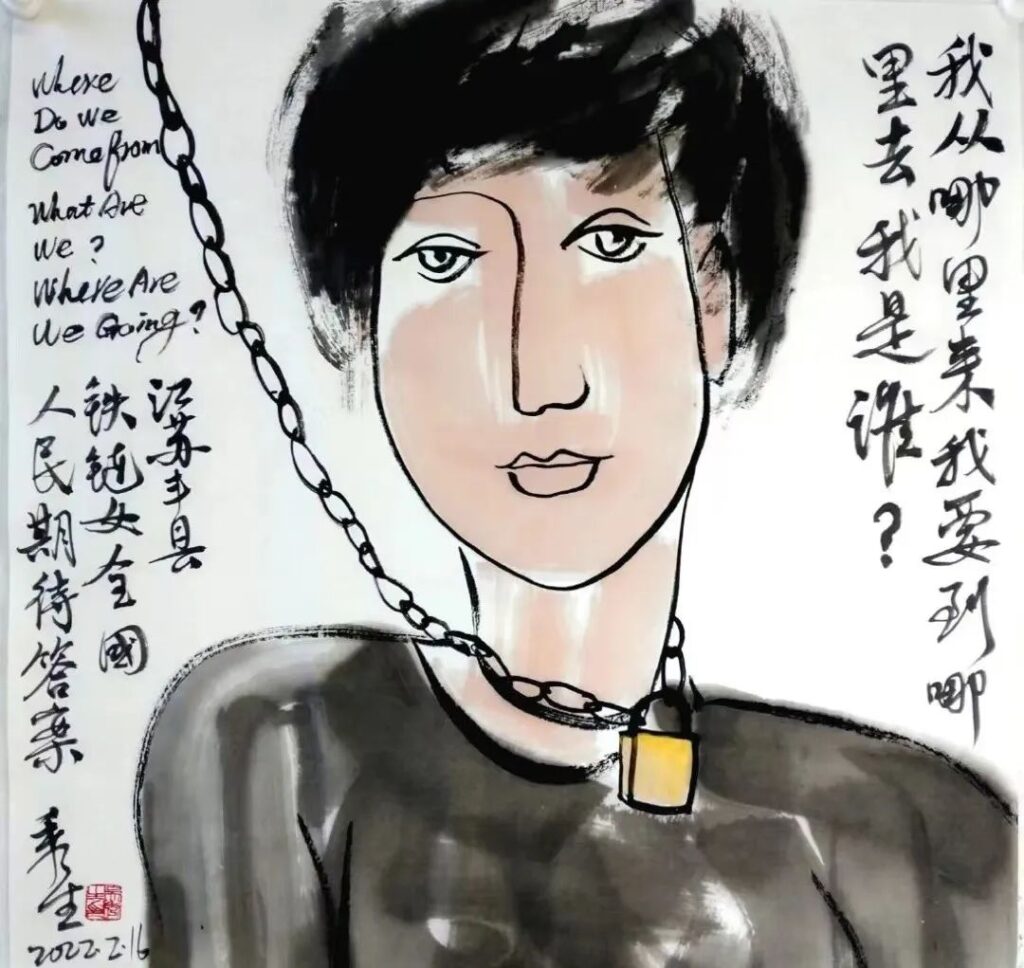

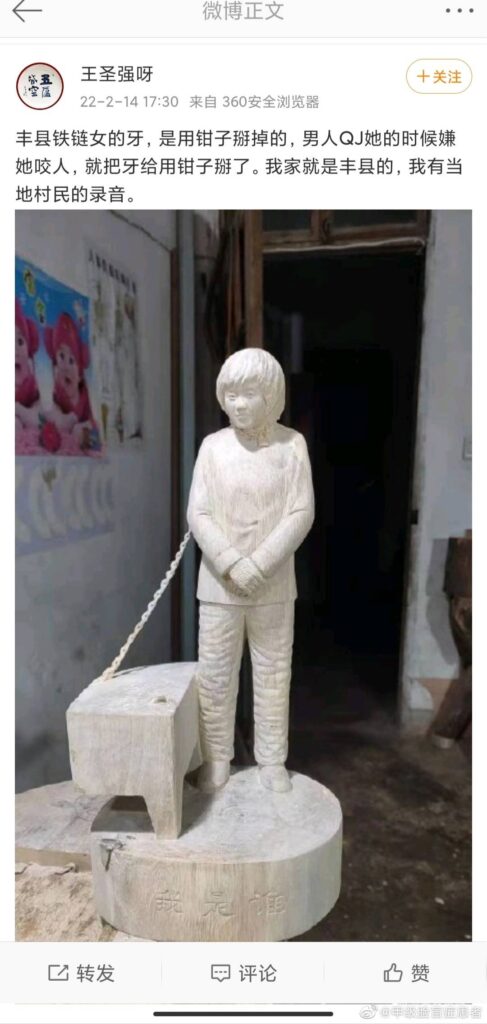

Artwork about the chained woman has also been circulating online, but so far we have not heard of any public exhibitions.

Women have been spotted on public transit wearing locks on their necks and shirts with messages such as “Continue following the Feng County, Xuzhou Incident, don’t give up!”

After keywords related to the chained woman were blocked on social media, people began disguising posts with titles such as “Is Eileen Gu Beautiful or Ugly?,” and memes have circulated with old photos of the Olympic gold medalist modeling a Tiffany necklace with lock pendant above captions such as “Thanks to Eileen Gu for speaking out about the chained woman of Xuzhou!” (Gu has not yet commented on human trafficking or capitalist patriarchy, to our knowledge.)

One ad hoc group called the Concern Group for the Woman of Feng County (丰县女子关注组) has proposed a list of demands and actions, but so far the actions have been limited to changing profile pictures to purple background and asking the Chinese state to crack down on human trafficking—despite many observers pointing out that the state has demonstrated complicity in this and other incidents at multiple levels, including in the letter of the law (whose maximum sentence for human trafficking is only three years, in the rare cases where such widespread incidents are taken to court). Instead, we suggest learning from the collective direct action of feminists in Mexico and Poland over the past few years, for example.

For more info and updates, follow the Concern Group’s page on Matters (Chinese only), CDT’s Chinese and English tags on the Xuzhou woman and human trafficking, the Wikipedia pages on the incident, and our Twitter thread.

A Young Bilibili Censor’s Death from Overwork

On February 4th, just after the Chinese New Year, a 25-year-old Bilibili employee who served as a team lead in AI-facilitated “content moderation”—a euphemism for censorship—died suddenly. Before his death, he was on 12-hours shifts, worked overtime regularly, and wasn’t allowed to take any days off for the New Year (despite official holidays for Spring Festival lasts 7 days). After this was reported on February 7th, Bilibili was quick to respond on the 8th , promising to hire more employees and decrease everyone’s workload.

Bilibili went to great lengths to try to suppress the news, for example attempting to bribe the Weibo user that had posted the exposé in exchange for taking it down. Bilibili didn’t attend the victim’s funeral after his parents informed the HR. His dual role as both a victim and a facilitator of oppression (as a censor) did not go unnoticed. As one commentator observed, his death ironically caused his former colleagues to work overtime in order to cover up the news.

In fact, online censorship creates a huge demand for workforce despite widespread application of algorithms. Usually a moderator like this could earn as low as 5,000 yuan (791 USD) per month working for Bilibili, and they have to take regular overnight shifts. Nevertheless, companies must always prioritize the imperative of profit as they develop—in the first three quarters Bilibili recorded a negative profit of 4.71 billion yuan (0.75 billion USD)—and human resources are just another cost they need to minimize.

A Young ByteDance Worker’s Death from Overwork

Later this month, on February 21st in Beijing, a 28-year-old ByteDance employee died suddenly. The news was shared by his 2-month pregnant wife. She explained that she was looking for a way to return the apartment to the developer, because she wouldn’t be able to pay the 30-year 21000¥/month mortgage for their apartment on her own, and that she would go back to her small hometown to raise her kid when this is over. The late employee’s chat history showed that before his death, he was “staying up every night, pulling an all-nighter every week” due to his work. The news was widely discussed on social media.

“Upon seeing the news, my parents solemnly asked me not to stay up too much, to assign less importance to work and money. Safety first, health first, etc. There is a hint of feeling fortunate in their tone, since they probably think their son isn’t involuting [as in engaging in involution] as hard, because their son isn’t in a big company. Although the pay isn’t great, at least he wouldn’t lose his life because of it. I didn’t have the heart to tell them that the industry I’m in pays less than ByteDance and requires harder work. And when employees suddenly die [from overwork], we don’t get as much attention as ByteDance.”

“Everyone is blaming the high real estate price on real estate sales companies. But who takes the lion’s share in a land sale? Sudden death from 996, everyone’s blaming it on capitalists’ exploitation, but who passed labor laws and refuse to enforce them? The story of the 8 kids in Fengxian, every official announcement contradicts the one prior. You think it’s because the rank-and-file is fucked, actually the higher-ups are also fucked. It’s only that the common people can’t see it because of their high ranks.” This post was deleted within 15 minutes of posting.

Yet Another Lockdown in Shenzhen

A sudden lockdown on the Shiyan subdistrict of Shenzhen showed that China’s nationwide, but highly localized, state power networks are still ready to spring into action anywhere, at any time, paralyzing the movement of people and goods at the drop of a hat. The city-wide lockdown of the city of Xi’an, covered in last month’s news round-up here, scared many across China, and other efforts at smaller-level lockdowns even led to isolated but impressive protests.

This month, while there were no signs of protests, the Shiyan lockdown showed that the local cellular state apparatus did show it could come out in force, anywhere and at anytime. In the early hours of Thursday, February 3rd, Bao’an district authorities ordered major roadways and intersections in Shiyan subdistrict to be shut down. The Shiyan subdistrict (街道) of Shenzhen’s Bao’an district is home to more than 300,000 people, in a city of 13 million. Images and video were shared on social media of hundreds of “health workers” in white hazmat suits gathering on the streets in formation, some posing for pictures. Lockdown measures were eventually lifted and by February 20th normal road traffic was restored in Shiyan.

China’s “micro-lockdowns” are due to continue, and for every confirmed case, it’s likely that there’s an apartment block or residential community under strict lockdown, involving hundreds of people. And of course, for each confirmed case and lockdown, there’s the ever-present possibility that lockdowns could spread to cover larger communities like Shiyan, that local state organs will mobilize, drawing hundreds or even thousands of actors into the control campaign.

For example, at the time of this publication, there are 47 officially locked down areas under “closed management” in Shenzhen, which has 180 cases of covid. The closed areas cover more than 100 different apartment buildings and office blocks, according to official platforms tracking virus control measures.1

Cantonese Not Ridiculed in This Year’s Spring Festival Gala

Conventionally, the Spring Festival Gala hosted by Central China Television is designed from the perspective China’s only official language of China: Mandarin. Other languages such as Cantonese are deemed as marginal “dialects” that often become the object of derision. But this year things went a bit differently: Cantonese was a major theme in a skit, and it was treated with less satire.

Still, not everyone felt comfortable with the way CCTV dealt with Cantonese this time. One poster on Zhihu (知乎, Chinese equivalent of Quora), commented that this skit reused some jokes from 1987 and was horrible about inventing phonological concepts. A commentary on Initium argued that this was proof that entertainers from Hong Kong and Taiwan were subject to different goals than in the 1990s, and that this was an “elegy of our time”.

While the political intention behind this skit (all parts of the gala must be examined closely by censors before going live) is clear as crystal – to push for further cooperation among Guangdong, Hong Kong and Macao within the “Greater Bay Area” by treating Cantonese in a less hostile manner, since it is the primary language in this area – the examples above show that this can be read in more ways than one.

After the tumult of the 2019 movement and continuing repression under the National Security Law, the Chinese state may also be trying to throw out a few bones of good will, such as complimenting Hong Kongers on their language and claiming it will still have a place after complete unification with the PRC. On the other hand, Hong Kong’s administration has become more economically reliant on the mainland (see our “Divided God”). Right now it seems unrealistic to replace Hong Kong any time soon, so “mutualism” may remain intact. Language is just a small part of this huge web.

The Debt Crisis behind Another Gala Skit

Another skit in this year’s gala was about a family’s debt crisis. The mainland Marxist platform Turbulent Current (激流网) sharply points out (in its article 小品《还不还》的背后,是严重的债务危机) that the plot is a reflection on commercial debt between individuals, and this is among a broader context of late market economy: stagnancies in various industries, general downfall of salaries, and a zeal for speculation. Ironically, such crisis reached its end simply by the counter-party’s moral motivation, and the primary means of struggle was mocked and discouraged. In the end, they write, this skit and the whole gala obscured the fact that this crisis cannot be overcome without fundamentally restructuring the socialist relations of production, rather than merely depending on moral suasion.”

Fans as Overseers of Olympic Mascot Production

Although reports about workers’ death from overwork emerged, people seemed not to care as long as those workers continued producing what people love – or in this case, what people see as a potential source for speculation. Bing Dwen Dwen (冰墩墩), mascot of the Beijing Winter Olympics, enjoyed an excessive demand compared to a limited supply, so much that people were said to pay some thousand yuan for it while the official price was just less than 200 yuan. This is partly because people were dying to find available means of financial gains, considering how the domestic stock market and real estate investment stay anemic.

According to a report, almost 900,000 viewers watched a livestream of five workers making plush toys of this mascot in a factory. It was around 8 o’clock at night, the workers worked nonstop, and the audience kept commenting “go, go, go!” or “work on that sewing machine until you collapse,” some complaining there weren’t enough workers on the job.

No one can tell the real starting point for this circulation, as the comment section of this article shows. Why so much frenzy for this single toy? Was it because Bing Dwen Dwen is so cute, or because it’s so ugly? Why would people believe such speculation could be dealt with by the state, but not survivors of human trafficking such as the chained woman of Xuzhou?

Meanwhile, Olympics Winner Eileen Gu Became A Proud, Patriotic Celebrity

Chinese-American gold medalist of freestyle skiing and fashion model—these are what come to mind when Eileen Gu is mentioned, so a little info about her background may be helpful. Her mother was the chair of an IT company in 1998, and her grandmother was a cadre in Ministry of Transport before retirement: a standard configuration for a bureaucratic family in China, with both political and business connections. In 2000 the mother went to San Francisco and worked in an investment company, and three years later Eileen was born. Since childhood Eileen had started skiing, and she could travel back to China in her summer vacations. In 2020 she was admitted to Stanford University.

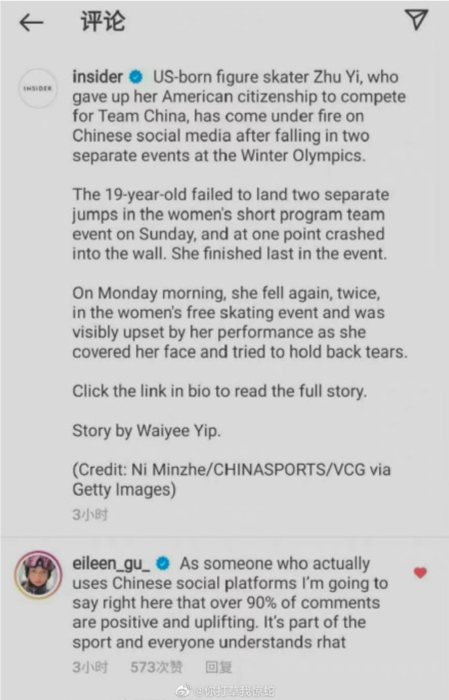

With such a successful background it is no wonder she could pick her own life or say anything as she likes, and so she does. In her Instagram post a comment asked about internet freedom (since Instagram is banned in China), and she answered “anyone can download a vpn its literally free”—apparently (or consciously) unaware that using a VPN to get around the Great Firewall and access banned websites is a criminal offense. In another news post about Chinese fans criticizing a skater, she asserted that 90% of comments on Chinese social media were positive—true in a way, considering posts such as screenshots of her comment about VPNs had already been censored on Chinese social media.

But the stark difference between her and the chained woman is vaster than a question of women having different experiences under different backgrounds. In 2021 the average of national disposable income was 35,128 yuan, about 5,560 US dollars. Most people in China simply live in a completely different universe than Gu, such as the two office workers who recently died of overwork (see above). They could not afford to live in San Francisco and travel between the US and China every year throughout their childhoods, and if they were lucky enough to find a white-collar job when they grew up, they could not enjoy a daily ten-hour sleep advocated by Gu as her “secret weapon.” Official propaganda like People’s Daily could praise Gu as “Glory of China” as they like, but that has nothing to do with people’s real living conditions.

New English Publications

The People’s Map of Global China

“The People’s Map of Global China tracks China’s complex and rapidly changing international activities by engaging an equally global civil society. Using an interactive, open access, and online ‘map’ format, we collaborate with nongovernmental organisations, journalists, trade unions, academics, and the public at large to provide updated and updatable information on various dimensions of Global China in their localities. The Map consists of profiles of countries and projects, sortable by project parameters, Chinese companies and banks involved, and their social, political, and environmental impacts. This bottom-up, collaborative initiative seeks to provide a platform for the articulation of local voices often marginalised by political and business elites. It is our hope that the information collected by this networked global civil society will be a useful resource for policymaking, research, and international advocacy.” (Made in China, February 4)

Dispatches from HKCTU

“An archival translation series of meditations on repression and labor organizing by HKCTU members” (Lausan, January 1)

Reorienting Hong Kong’s Resistance: Leftism, Decoloniality, and Internationalism

“new co-edited anthology on Hong Kong’s cultures of resistance from Palgrave. The essays bring together radical activist voices with local and diasporic leftist analyses of Hong Kong’s socio-political condition in a global context.” (Lausan, February 3)

For Uyghur torchbearer, China’s Olympic flame has gone dark

“In the years since he took part in the Olympic torch relay and later attended the Games as a representative of his home region of Xinjiang, in western China, Beijing has imposed harsh policies on the Muslim Uyghurs, splitting apart Yalqun’s own family.” (AP, February 3)

‘A bed of nails’: China’s #MeToo accusers crushed by burden of proof and counterclaims

“Two Chinese women who claimed they were violated by powerful men were then sued by their alleged assailants for defamation. Activist says Beijing’s crackdown on feminists in recent years, coupled with male-dominated power, may push more women to fight back against oppression.” (SCMP, February 2)

Chinese Fans Demand Equal Pay for Women’s Soccer Team After Win

“China’s historic win at the 2022 AFC Women’s Asian Cup final on Sunday has prompted campaigns calling for equal pay in sports at home. A 2018 report showed fewer than 20% of female soccer players earned over 10,000 yuan ($1,570) per month.” (Sixths Tone, Feburary 7)

‘Ascension’ and the Chinese Dream, with Jessica Kingdon and Kira Simon-Kennedy

“Andy talks with the director (Jessica Kingdon) and producer (Kira Simon-Kennedy) of the new film Ascension, a documentary about working life in contemporary China…. The film features scenes of quotidian working life in a period when the government has begun to promote the “Chinese Dream,” spanning textile and sex doll factories to etiquette school and social media influencers all the way to luxurious water parks and tropical vacation resorts. Together, these scenes raise provocative questions about China’s blindingly rapid development, the uneven pace of upward mobility, and whether China is an exotic outlier or a recognizably modern society, comparable with life in the US and other societies worldwide.” (Time to Say Goodbye, February 1)

Also see: Letting Sleeping Dogs Lie, Or How I Found My Family in China

Filmmaker Jessica Kingdon for Talkhouse, December 2021

Previous Monthly News Highlights

Drinking Algae, Folding Beijing, Fighting Lockdowns: News Highlights, January 2022

Fake Capital, Persecuted Speculators & Exploited Enterprises: News Highlights, December 2021

Notes

- For detailed accounts and analysis of how the covid-19 pandemic has been experienced by ordinary people in China and responded to by the state there, see our 2021 book Social Contagion and Other Material on Microbiological Class War in China.