We are pleased to share this translation of an interview with Khun Heinn, a participant in the ongoing Spring Revolution and co-founder of the Progressive Muslim Youth Association (PMYA). The interview was conducted by a member of the transnational Sinophone Palestine Solidarity Action Network (PSAN) last month, during a meeting in Thailand, then collated, translated into Chinese and published with an introduction on the PSAN Substack.1

Khun Heinn is a Muslim from Yangon currently living in exile in Thailand. Burma2 is home to multiple Muslim communities from several different ethnic groups, but all have been designated by political authorities (including not only the junta but also the liberal National League for Democracy) from the majority Buddhist Bamar as kalar (a racial slur meaning “people from the West”), thus not deserving of rights within Burma’s federal community. Khun Heinn identifies politically as “libertarian communist,” but the PMYA is more broadly left and predominantly social democrat, with a mission of building bridges between the Burmese revolution and the Palestinian struggle, as explained in the interview.

The PSAN describes itself as “a group of Sinophone activists organizing across multiple continents. We are working on educating our communities on Palestinian resistance and the global solidarity movement, as well as calling attention to China’s complicity in Israel’s occupation, apartheid, and war crimes against Palestinian people.” Their other writings and activities can be found on their Substack and Instagram.

For more stories about the experiences of Burmese revolutionaries and Muslims living in Thailand, see “Dispatches from Mae Sot” in the forthcoming inaugural issue of Heatwave magazine. For background on the persecution of Muslims in Burma, see “Three Theses on the Crisis in Rakhine,” and on the 2021 coup and subsequent revolution, “Until the End of the World” and “Unhappy is the Land That Needs Heroes,” all by Geoffrey Rathgeb Aung. For more English translations of Chinese texts on Palestine, see “Against Pinkwashing” and “Palestine and Xinjiang under Capitalist Rule.”

PSAN’s Introduction

It has been over four years since the military coup in Burma on February 1, 2021. Were it not for the devastating earthquake that recently struck, Burma would have been all but forgotten by the international community. Yet, throughout these four years, resistance has never ceased. The non-violent “Civil Disobedience Movement” was brutally suppressed by the military shortly after the coup—protesters were arrested, tortured, and killed. Subsequently, some responded to the call of the National Unity Government (NUG) in exile by fleeing into the jungles to form the People’s Defense Force (PDF), joining forces with ethnic armed organizations (EAOs) in guerrilla warfare. Others fled to other countries, Thailand being the first stop for many of them.

Over the past few decades, Muslims from Burma have migrated to the Thai border town of Mae Sot, contributing to the formation of a transnational Muslim trading network—one that also includes Thai and Pakistani Muslims. Later, several waves of anti-Muslim riots and systematic persecution within Burma have driven many other Muslim migrants across the border.

Mae Sot [official population 50,000, but with an estimated 100,000 migrants from Burma] thus hosts a large Muslim population [estimated 5 to 10 percent of the total] whose lingua franca is Burmese. Muslim-owned shops are everywhere, and it’s not strange to see people on the streets wearing keffiyehs there, despite the town’s distance from major cities. Many in this long-established Muslim community are passionate about the Palestine cause but remain largely indifferent to Burma’s revolution, seeing it as a conflict between the military regime and the Bamar majority—irrelevant to their lives. Since the 2021 coup, Mae Sot has also become a haven for those involved in the resistance movement who have been blacklisted by the military and can no longer leave the country legally. Among them are Muslim revolutionaries, some of whom occasionally manage to find work at Muslim-run trading companies in the area.

After the outbreak of the Gaza war in October 2023, I witnessed how the distant issue of Palestine mirrored the complex ethnic ecology of Burma. The exiled communities quickly descended into anxiety and division. Muslim revolutionaries reported that they were seeing Islamophobic sentiments resurface among exiled Bamar revolutionaries within their own circles. After the 2021 coup, many Bamar dissidents had expressed remorse toward the Rohingya, regretting their previous silence during the oppression of the most persecuted Muslim group in Burma. But now, to the dismay of Muslim revolutionaries, some Bamar comrades had started echoing Israeli narratives, accusing Muslims of being terrorists. Disillusionment spread among many Muslim revolutionaries: they began to believe that the expressions of regret by Bamar dissidents after the coup were merely performances for the international stage. The revolution, they said, remained Bamar-centric. Another layer of mistrust took root: perhaps Burma’s ethno-nationalist politics had only been temporarily patched over by the coup and the revolution. Would Islamophobia and Bamar chauvinism resurface in a post-revolutionary Burma?

The earthquake on March 28, 2025, came at a time when USAID had been cut off by the Trump administration. For Burma, already fragile from civil war, this was yet another blow. More than 8.5 million people were affected by the earthquake, joining over 3 million who had already been displaced. At the same time, around 20 million people—roughly one-third of the country’s population—had already been already living below the poverty line even before the disaster. It was thus a truly devastating catastrophe. Any potentially positive role in disaster relief had been precluded by the atrophy of the state’s emergency management agencies under the military’s war against its own people.

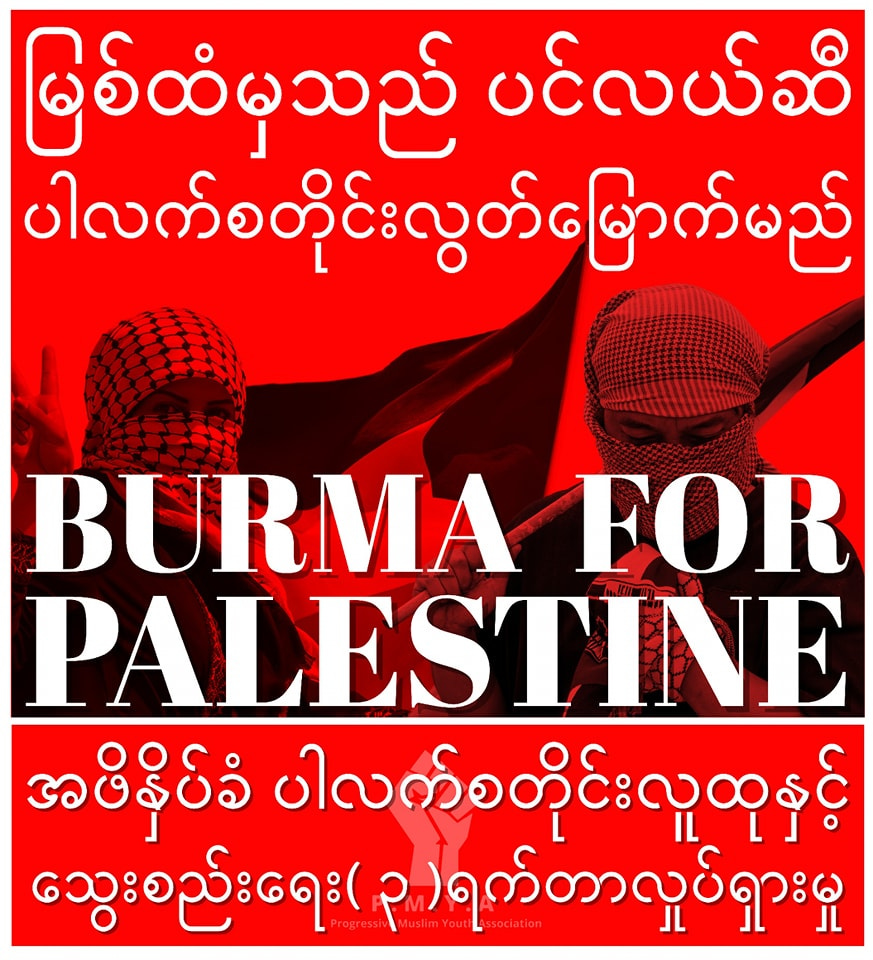

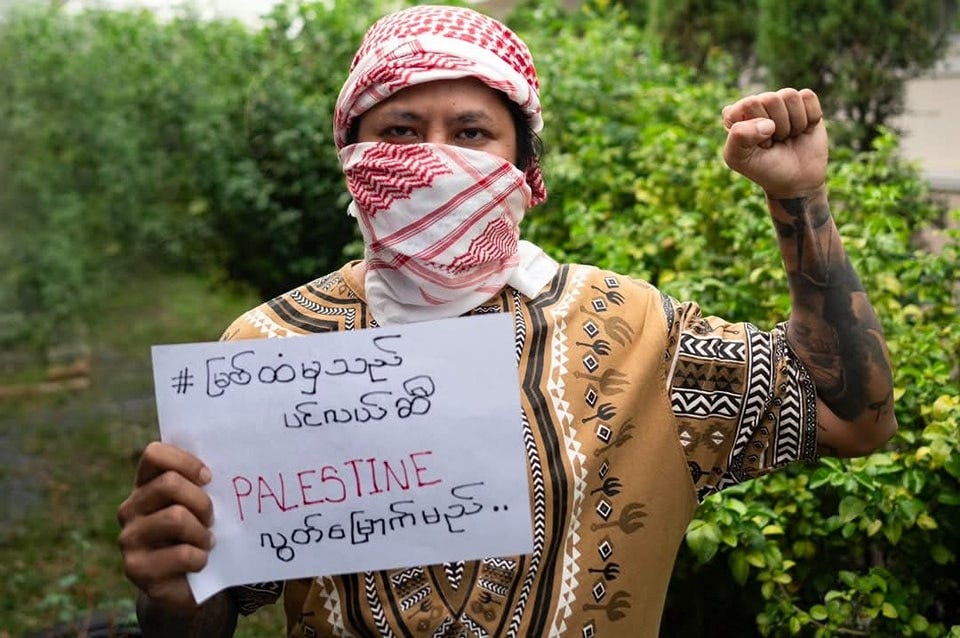

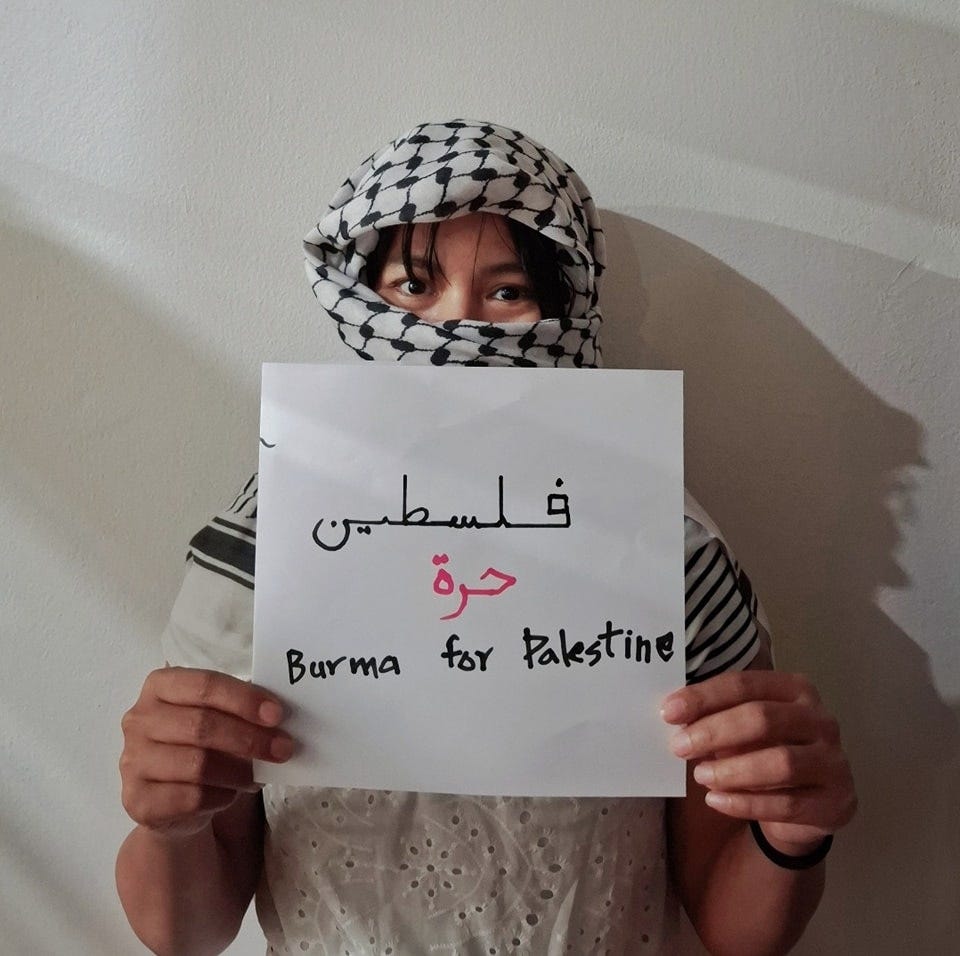

On the other side of the world, Israel’s genocide in Gaza continued unabated. Two weeks after the “3/28 Earthquake,” the leftist Burmese Muslim organization Progressive Muslim Youth Association (PMYA) launched an action titled “Burma for Palestine.” The campaign attempted to link the suffering of the Burmese people with that of the Palestinians, reminding Burmese citizens not to forget: Gaza has been enduring a disaster of earthquake-level destruction every day for over a year and a half—but unlike Burma’s natural disaster, Gaza’s catastrophe is artificial.

In March 2025, I interviewed Khun Heinn, a Burmese Muslim exile in Thailand and member of PMYA. I asked him to speak about the social ecology of Burmese Muslims, their place in the revolution, and why the issue of Palestine holds such profound significance for their struggle.

Interview

PSAN: After October 7, 2023, Palestine became a divisive issue within Burma’s revolutionary circles. In this context, how does your organization respond to these layers of tension?

Khun Heinn: Yes, they call us kalar and we’ve never truly been accepted by Burmese society. After the coup, some of them suddenly began to repent—apologizing for standing with Aung San Suu Kyi and the military during the Rohingya genocide [which peaked in 2017]. But after October 7, their true colours reappeared. Some started saying “Muslims are terrorists” again. So yes, this has certainly become a divisive issue within the revolution. For us, October 7 felt like a return to 2017—all the anti-Muslim hatred came flooding in. This is the result of a lifetime of brainwashing under military rule and Western governments’ agenda on Muslims. Even though many of them now oppose the military, that deep-rooted Islamophobia is still there.

When I was a child, there was a military-issued weekly magazine called World Affairs. It was full of stories painting Muslims as terrorists—talking about suicide bombings, car bombs, and all that. These narratives were actually imported from the U.S., lifted wholesale from the post-9/11 “War on Terror” discourse. The Burmese military is known for being anti-Western, yet they fully adopted Islamophobic counterterrorism rhetoric from the U.S.

nAfter the 2021 coup, many Bamar dissidents apologised, but we’ve never held expectations for the Bamar-dominated mainstream society. Without structural solutions, these apologies are just performances for the international stage. ‘We don’t believe reconciliation can happen like that.

For us, the struggle is more complex than what Bamar revolutionaries have been facing after the coup. We’re up against the military, yes—but also against the oppression from mainstream chauvinist organisations in different ways, like political ways. People said, what’s most important now is that we are in a time of war. We must organize and fight, yes, but we must also end other forms of oppression as well.

PSAN: But how can the Muslim community in Burma be convinced that this revolution is also THEIR revolution?

Khun Heinn: Yes, that’s very difficult. Muslims in Burma have always been called kalar, and many of us feel like guests in a foreign land, as the military’s propaganda describes us. It’s rare for us to feel that this is our land—something we must reclaim from the military. Even during the NLD (National League for Democracy) government, Burma remained dominated by the chauvinism of the Bamar and other nationalities. Muslims were still oppressed. Some of my friends were even imprisoned for speaking out during Aung San Suu Kyi’s time in power. However, democracy is still far better than military rule—at least people didn’t just disappear in the middle of the night without a trace.

I think the first step is to let people understand that the collective suffering of Muslims is largely caused by this military regime. Before the 2021 coup, the Bamar majority wasn’t nearly as hostile to the military. Now, they’re the most active in resisting it. We need to seize this valuable moment, fight alongside the Bamars, and demolish the narratives of the military.

At the same time, we all know that this isn’t enough. In the vision of the new Burma, there is no place for Muslims according to the political agreements and conditions. For example, under the 1982 Myanmar Citizenship Law—we call it “the Nazi Law”—there are no governmental representatives for Muslims, other religious minorities, or ethnic minorities without territory in the NUG (National Unity Government). The proposed federal system doesn’t include the political participation of minorities without territories or armed power.

So, while we must fight with others against the military, we must also fight for ourselves within the revolution. The former demands we take up arms; the latter is a battle of political discourse—to assert our demands and claim our political rights. For us, the road to revolution is long.

PSAN: Many people don’t realize how diverse Muslim communities are in Burma. When people think of Muslims in Burma, their first reaction is usually “Rohingya.” Can you tell us more about the practices and involvement of Muslim communities in the revolution?

Khun Heinn: I have a good example for this: I am one of the founders of the Muslims of Myanmar Multi-ethnic Consultative Committee (MMMCC). It’s a coalition of different Muslim organizations trying to represent Muslims from different ethnic groups, including Rohingya, within the imagined framework of a democratic federal Burma after the revolution. Even though we are all Muslims, there are still many different needs based on where you come from and which ethnic group you belong to, but the Bamar majority treats us all the same way.

We ask ourselves: how can we, as Muslims, live within that system? You know, it’s extremely difficult to be Muslim in Burma, no matter which region or state you live in. For another example, there are Rohingya in Rakhine State, but there are also many Chinese (Yunnanese) Muslims in Mandalay, South Asian Muslims, Bamar Muslims, and Muslims from other ethnic groups spread throughout Lower Burma. The 1982 Citizenship Law and other forms of structural violence have long excluded Muslims from the identity of being “Burmese”.

Muslims in Burma are incredibly diverse, but the dominant society doesn’t care what your background is—if you’re Muslim, you have to face structural discrimination. That’s why we’re building this cross-ethnic Muslim coalition, inviting all kinds of Muslim organizations to be part of this consultative mechanism. We also need to craft a more inclusive political identity—one that can hold space for all Muslim communities.

I also belong to an organisation called the Progressive Muslim Youth Association (PMYA). After the coup, I founded PMYA together with a group of young Muslim comrades. As part of the resistance against the military junta, we wanted to bring the issue of Muslim rights to the table. In addition to the PMYA and the MMMCC, I work with a media platform called Intifada.

In the PMYA and Intifada, we emphasize the word “progressive”—organizing Muslims to challenge patriarchal and conservative values from within. Our media is called “Intifada” to highlight the importance of the Palestinian struggle and the resilience of Muslims from Burma. We aim to connect the struggle of Muslims in Burma with that of Palestinians—and even with the broader struggles of Muslim communities worldwide.

PSAN: Why is the issue of Palestine particularly important to you?

Khun Heinn: Because imperialism and ruling classes wear different faces in different contexts, but they are deeply connected. In the context of Burma, we local Muslims are the Palestinians.

In Burma, the mainstream view is that if you support Palestine, you’re supporting Hamas. They think intifada equals Hamas violence. There’s very little understanding of the political and historical context of the Palestinian liberation movement. But politically, I prefer to position ourselves with the the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP)—the progressive, leftist branch of the movement. Since October 2023, we have been trying to study and understand the Palestinian movement more deeply. At its core, it’s a struggle against territorial occupation.

For many Muslims in Burma, the brutal bombings of Gaza and the genocide of Palestinians by Israel are clearly visible. The role of the United States is also obvious. So many in the mainstream Muslim community support the Hamas-led resistance. Their solidarity with Palestinians is built on that support for Hamas. But this also contributes to a growing conservatism within Burma’s Muslim community. For example, driven by anti-U.S. and anti-imperialist sentiment, some even express support for the Taliban. That is the thing that we have to try to change.

That’s why PMYA is doing internal work within Muslim communities by introducing leftist factions of the Palestinian resistance and their ideas. We’re trying to shift the dominant view within Muslim communities. Their perspectives on the Palestinian liberation movement are deeply connected to their lived experience as Muslims in Burma—including how they practice their religion.

To us, if the junta is just simply overthrown, Muslims will remain marginalized, and Muslim communities will continue to live under conservative and patriarchal norms, while some other ethnic groups remain deeply nationalist. If we can’t change the old ideas, then what has actually changed after the revolution? It may look different on the surface, but in essence, nothing will have changed except the specific group of people running the state. So, even though we’re in over the fourth year of the post-coup revolution, we feel like the real revolution hasn’t even begun.

After October 7, we issued statements and took many steps to intervene in the discourse—not just toward Muslim communities, but toward the broader society throughout Burma. We consistently raise the issue of the West’s oppressive role in Palestine, and we argue that our revolution cannot rely on the West, especially not the United States. They are absolutely not trustworthy allies.

PSAN: The Spring Revolution has indeed been “favoured” by the Western establishment to some extent. The NUG has consistently received support from the United States, which also seems to be the Western country that has taken in the most Burmese exiles since the coup. Many international NGOs working on Burma issues are also funded by USAID. In this sense, it’s very difficult for Burmese revolutionaries to take a stance on Palestine that goes against that of the U.S.

Khun Heinn: Our positions are never influenced by the stances of any establishment. For example, we have always spoken openly and critically about the NUG, about Western imperialism, and about China.

PSAN: The USAID cutoff is having huge consequences on Southeast Asia, especially Burma-related issues. Can you share your thoughts on it and how it is affecting war-torn Burma and the revolution?

Khun Heinn: Education and healthcare for displaced populations have been central to the impact of the recent USAID funding cuts. Following the coup, many students involved in the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) withdrew from the formal education system. In response, several remote learning platforms emerged to support these CDM students in continuing their education and to provide employment for CDM teachers. Some of these initiatives had been receiving funding from USAID. Compared to central Burma, the cutoff has had more significant consequences for refugees along the borders, further straining access to essential services.

For the Burmese exiled to Thailand after the coup, the situations of different organizations are different. Some rely on applying for funding from international organizations to sustain their operations, while others depend on donations from the Burmese diaspora, which is a form of grassroots mutual aid. Our organization operates through this grassroots mutual aid model to raise funds, and most of our work is also unpaid activism.

Also, for the exiled groups on the Indian-Burma border, USAID was never able to reach the NGOs and CSOs (civil society organizations) there.

PSAN: Before the USAID funding cutoff, some of my Burmese comrades used to say that the revolution has been corrupted by international NGOs. How do you see it?

Khun Heinn: I would like to use a quote from Thomas Sankara (first

President of Burkina Faso, a Marxist and Pan-Africanist revolutionary), “He who feeds you controls you.” You know, all the groups have to write proposals to fit into their agendas and to write a report for each activity for the donor. It has become pretty much a donor-driving project, which means it’s not for the community, but for the donor.

“We don’t have our own territory, so federalism has never been our solution. …

This kind of federalism could actually give rise to stronger forms of ethno-nationalism than we have today.”

PSAN: In my observations over the past two years of the revolution, it seems that among all the groups involved, Muslims are the most radical and politically imaginative. Most other groups cling to the unfinished dream of federalism, with ethnic minorities having their own semi-autonomous states. Some Bamar revolutionaries have even proposed forming a “Bamar State” in Lower Burma. But this is a form of ethnic purification that simply reproduces the logic of the nation-state. In reality, the central lowlands of Burma have long been home to a mix of different ethnic groups. Even many upland regions, like Shan State, are highly mixed. If we imagine the future of Burma through this purist lens, we can easily foresee that in places like Rakhine State, where the Rakhine people will gain more power, the Rohingya—who lack a state of their own—will face even greater oppression. In fact, as the Arakan Army gains ground in Rakhine, the nightmare is already returning for the Rohingya. Yet in my interactions with revolutionaries, most Bamars simply buy the narrative of NUG’s federal vision. Only the Muslims seem unconvinced. Because Muslims have long lived dispersed across the country and are made up of various ethnic backgrounds, federalism has never truly been a solution for you. And under that premise, I’ve seen new political imaginaries and practices emerging. Can you tell us more specifically about them?

Khun Heinn: Yes, the dominant post-revolution vision right now is democratic federalism. But federalism shouldn’t become another form of boundary-making. We don’t have our own territory, so federalism has never been our solution. That’s why we’re looking for alternatives—not based on territorial boundaries, but on cultural autonomy.

This kind of federalism could actually give rise to stronger forms of ethno-nationalism than we have today. That would eliminate our ability to do organizing work across federal boundaries. We wouldn’t be able to unite under a common banner. But our struggles are interconnected, and we need to stand together.

Within the context of the Spring Revolution, Muslims are an oppressed group. We can’t assume the revolution will bring us meaningful change, so we must be more radical than others. And Muslim women—who are even more oppressed among Muslims—tend to be even more radical.

We’re now promoting a new political concept: “non-territorial autonomy.” This concept is crucial to us. Compared to many other minority ethnic groups, we don’t have a territorial base from which to exercise autonomy. The strategy of the Rohingya has been to assert that they are the indigenous people of Rakhine State.3 But most Muslims in Burma are scattered throughout the country. So how do we imagine collective political rights in a post-revolution society? We must go beyond the limitations of territorial boundaries.

This idea of non-territorial autonomy is still very new, and it hasn’t become widespread yet. But we believe it has broader applications. For instance, the Chinese community in Burma is also dispersed and has long been denied recognition as a distinct ethnic group. Or take the case of Karen, Mon, or Shan people who were born and raised in Yangon rather than in their traditional homelands. Their ethnic identity is detached from where they live. They, too, need an alternative political framework—one that doesn’t force them into becoming “Bamar.”

Under this framework of non-territorial autonomy, we’re not trying to set up our own governmental institutions. Muslims living in different regions would still fall under their local administrative jurisdictions. But what we demand is collective rights, including proportional political representation within those local governments. We also want our own welfare system across the country—education, healthcare, and so on. In mainstream society, the needs of Muslims in these areas are constantly overlooked. And considering that Muslims have lived under long-term structural inequality, having even been stripped of basic citizenship rights, we must demand equity, not just equality. That means we, as a marginalized and historically dispossessed minority, should be given specific consideration in how resources and opportunities are distributed.

I was born and raised in Yangon among Bamars. My face told me that my ancestors migrated from South Asia. But I do care about my life on this land, the land I was born in, the land my parents and grandparents were born in. I drink Indian tea after the Burmese mohinga [the “national dish” consisting of fish soup with rice noodles] in the mornings. This is how I grew up. I am a partisan against the junta, so this revolution is my revolution, too.

Notes

- Header image: August 2021 March in Yangon (including the PMYA and other left groups) on the anniversary of the Rohingya genocide, calling for the rights of ethnic minorities, while also demonstrating solidarity with the Palestinian struggle. Credit: Ko Htet.

- “Khun Heinn” (a pseudonym) prefers to use the English term “Burma” instead of “Myanmar” because of the latter’s association with the ruling military regime since its official adoption in 1989, so we have followed suit. Other Burmese leftists prefer “Myanmar” despite this association because “Burma” (also preferred by the liberal National League for Democracy) is linked more closely to the Bamar majority (also known as “Burmans,” comprising about 69% of the population), as well as to British colonialism. Both terms are identical in Burmese, the different English spellings representing literary vs. colloquial pronunciations, and both derive from the Bamar term for their own ethnic group.

- Before the Rohingya genocide, mainstream Burmese society had never heard the term “Rohingya.” They referred to them as “Bengalis,” implying they were illegal immigrants from Bangladesh. The term “Rohingya,” meaning “people of Rakhine,” is a political self-claim to identity and recognition since a long time ago. (Note by PSAN.)