Below is our translation of an article by Canyu (惭语 “Shameful Words”). The author is a communist from mainland China who works with the cross-border network of internationalist activists whose collective piece “Against Pinkwashing: Sinophone Queers and Feminists for Palestine” we published in March. According to the author, this piece was written out of political concern, and they are not a professional researcher. Instead, Canyu hopes the article will contribute to the development of sympathy among “the Chinese pan-dissent community” for the conditions and struggles of both Palestinians and Uyghurs, and that it will also help to short-circuit the political frameworks of pro-Western Chinese liberals, on the one hand, and anti-Western Chinese nationalists, on the other, who normally position themselves in one “camp” against another when it comes to discussions of these two oppressed groups. Like the earlier piece produced by their collective, Canyu’s article offers valuable insights into a strong desire among Chinese comrades to extend the critique of Israel’s horrific war on Gaza to the PRC’s subjugation of Turkic Muslims. In this case, the author focuses on the way that both colonial states have controlled the labor of the colonized. We present this text as a way to better understand and support internationalist currents emerging from the Chinese left, and as a contribution to the ongoing wave of global resistance to the genocide in Gaza.

In the spirit of comradely critique, we offer a few clarifications in this preface. First, while we support the sentiment of emphasizing commonalities between specific instances of oppression under the rule of capital, in this case the differences are also striking: The author’s focus on labor makes more sense for the PRC, whose colonial policies seem to have been partly organized around the goal of transforming Turkic Muslims into a disciplined workforce cut off from any cultural continuity with their histories of resistance. Israel, by contrast has shown less interest in the labor potential of Palestinians, particularly in Gaza. Palestinians experience some of the highest unemployment rates in the world, which have hovered around 50 percent in Gaza for many years, and around 15 percent in the West Bank—where reliance on Palestinian labor has historically been more central to the colonial project. After October 7th, the 4th quarter 2023 unemployment rates in Gaza jumped to an unprecedented 75%. By contrast, unemployment in Xinjiang is relatively low, and increases in unemployment are used as a pretext for proactively shipping off ethnic minority populations across the country in jobs programs. While Canyu’s comparison makes more sense for the West Bank, Israel’s treatment of Gaza would be better understood as an extreme example of the “surplus population”: the portion of the proletariat rendered unnecessary for capitalist needs, thereby becoming not an object of potential exploitation, but merely a problem to be managed—whether through abandonment, incarceration or murder.1

Secondly, while the article emphasizes China’s use of re-education camps, or what the state has infamously called “vocational training facilities,” these sites have largely been converted or shut down since 2019, as the state shifted strategies in its latest policy permutation. This is not to say that the situation has improved for Turkic Muslims. Many of the “training facilities” were merely converted into ordinary prisons. For those inmates who were released rather than formally becoming prisoners, the state has continued a policy of labor transfer under the guise of poverty alleviation campaigns, relocating Uyghur labor to factories across the country.2 Meanwhile, the PRC recently moved to “normalize counterterrorism,” a shift that will likely further institutionalize the subjugated position of Turkic Muslims in Chinese society. There is currently no Israeli equivalent to the “training facilities” that became so notorious in Xinjiang. Instead, the Israeli state sees itself faced with a massive, unemployed, war-ravaged population often portrayed as sub-human, and has never posed any strategy for incorporating this population into its national workforce. Instead, it is currently planning to place Gazans in cordoned off “bubbles” while it continues its military campaign in other parts of the Strip.

In addition, while the author mentions Israel-China security relations in passing, here we would like to highlight that China and Israel have a long history of cooperation on “counterterrorism,” directed at Palestinians, Uyghurs, and the broader population. For example, China publicly sought out Israeli counterterrorism experts at the height of its crackdown in 2014. Similarly, China has invested billions of dollars in Israel’s high-tech sector and has served as the country’s second largest trading partner in recent years (behind the United States). To this day, China’s Hikvision cameras aid in the mass surveillance of Palestinians and others in Israeli society.

We’d also like to note that this article exemplifies a growing concern with the plight of Palestine in China, which appears to be more widespread than it has been in decades—despite the state’s strategic ambiguity on the issue and repression of any domestic activities that could be interpreted as “protest.” Semi-public film screenings and discussions have been organized among young activists in several cities over the past few months, and beyond that narrow milieu, recent weeks have even seen small-scale political actions by high school students. These students used brief media appearances during their post-exam celebrations to call for Palestine’s liberation. While such calls at first seem to be not so distant from China’s nominally pro-Palestinian position, the actions themselves were not welcomed by the state, perhaps because they risked drawing too much attention toward China’s empty posturing on this issue, while it has long maintained cozy relations with Israel. Some of these posts were deleted from social media, and a video of one incident shows students being taken off-camera by police. The demonstrations, as well as the piece below, illustrate why expanding the discussion of Palestinian oppression is in direct conflict with the Chinese state’s own interests.3

Finally, we’d like to emphasize that this article is one of only a handful of Chinese texts we’ve seen attempting to link the plight of Palestinians to that of Uyghurs (along with “Against Pinkwashing” and two of the sources cited below), and it’s the first non-academic piece we’ve seen that draws on extensive research using a broad variety of Chinese and English sources. It digs deep into the history of colonialism, land tenure, and labor conditions in both regions—attempting to clarify the facts and provide a Marxist theorization for young Chinese readers who have only recently begun to learn about these issues. We therefore consider it a milestone in the development of 21st century Chinese internationalism.

From Palestine to “Xinjiang”:

Forced Labor and Capitalist rule

Canyu4

Since October 7th of last year, many analyses have pointed out that Israel and China have borrowed “counter-terrorism” tactics and surveillance techniques from each other in the context of genocide and settler colonization, but there has been little discussion of the similarities between the two in terms of forced labor and the rule of capital. Indeed, the forced labor of Palestinians is little known in the Chinese-speaking world or internationally. For a long time, Israel and the West, led by Europe and the United States, have used hasbara5 and neoliberal discourses to hide their colonial plunder of Palestine, while today China and Russia are also whitewashing their own imperialist practices by aligning themselves with authoritarian governments and projecting an image of leading resistance to Western hegemony. In this way, “choosing sides” has become the norm. Many liberals call for Uyghur human rights but support Israel’s genocide, while “little pinks” (小粉红 i.e. young cyber-nationalists) and “tankies”6 clamor for the liberation of Palestine but dismiss the labor camps in “Xinjiang” as a hoax concocted by US imperialism. While they seem to have very different political stances, both have fallen into the trap of the new Cold War narrative created together by the two capitalist blocs of liberal and illiberal “democracy.”7 Thus, discerning the relationship between capital and forced labor/settler colonization is particularly important at the present time. With a little comparison, we can see that the structures of oppression for Palestinians and Uyghurs are extremely similar: state-initiated and capital-driven. This article will analyze the structural similarities and differences between forced labor and capital exploitation of Palestinians and Uyghurs from a left-wing perspective. The author hopes to dispel the myth of campism and call for inter-racial/-ethnic/-national proletarian solidarity against the oppression of colonization, capital and totalitarianism.

Forced labor in concentration camps/prisons

Research by Palestinian historian Salman Abu Sitta found that as early as 1948-1955, the Zionists established at least 22 concentration camps alongside the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians, imprisoning some 7,000 Palestinians.8 Sitta notes that the Zionists wanted to establish a Jewish-ruled regime, and therefore initially viewed Palestinian civilians as a burden, planning to remove them from their homes but not to imprison them. However, Israel’s declaration of statehood caused widespread discontent in neighboring Arab countries such as Syria. These countries sent troops into Palestinian territory to fight Israel. At that point, Israel began to build concentration camps for holding prisoners of war. On the other hand, there was an urgent need to fill the labor gap as tens of thousands of Jews were drafted into the army. So along with the POWs, Israel also began to intentionally hold large numbers of Palestinian civilians as “POWs” (there were not many Palestinian POWs held by Israel before then) and forcibly requisition them for the colonial economy. In the camps, Palestinian prisoners were forced to work as domestic servants and laborers on wetland reclamation projects. In addition to public service, Palestinian prisoners were even forced to participate in military labor against their own people—transporting the wreckage of destroyed Palestinian homes, collecting and transporting the looted belongings of their compatriots, digging trenches, and burying the dead. Ironically, the Jews inaugurated these camps only three years after Germany closed the camps where Jews were held; the people who operated these camps also happened to include Jews who had been imprisoned by the Nazis.

In addition to the concentration camps, Israeli prisons have been a bloody site of forced labor for Palestinian political prisoners. According to a report by the Addameer Association, from 1967 to 1972, Palestinian prisoners held by Israel were forced to produce military equipment such as tanks for Israel—naturally used in the repression and massacre of Palestinians—and “hired” to build prisons for their own people.9 According to Ralph Schoenman, author of The Hidden History of Zionism, politicized prison labor is forced labor that “disturbs the lives of the prisoners” and is designed to “maximize physical and psychological stress.”10 During forced labor, Palestinian prisoners were subjected to dehumanizing abuse and torture. Refusal to work was punished by the withholding of cash vouchers, of time off from work, and of books and newspapers, along with punishment by isolation and beatings. The average wage for this labor was a mere $0.05 per hour (equivalent to 0.3-0.4 Chinese yuan).

The Addameer report also notes that although Palestinian prisoners forced Israel to abolish the explicit forced labor system in prisons through a hunger strike in 1972, compulsory work continued in another, more insidious form—the prison canteen system. At first, some basic food and supplies for Palestinian prisoners were provided free of charge by the International Red Cross. In the 1970s, however, this was replaced by the canteen system. As the quantity and variety of basic provisions (hasbaka) decreased and the quality of meals declined, Palestinian prisoners were forced to rely on the commissary and to perform “voluntary” work in exchange for canteen credits to purchase necessities. This exploitation of Palestinian prisoners’ labor was gradually phased out after 1980, but the commissary system continues to this day, with economic exploitation being transferred from the prisoners to their families: those outside the prison need to earn money in order to fund expenses of those on the inside.

In “Xinjiang”, as early as the Mao era there were “reform-through-labor (laogai) camps (劳改营)—the predecessors of today’s “re-education camps” (再教育营). The former differed in that they were not intended for ethnic minorities only, but for dissidents of all ethnic groups. It is undeniable, however, that the real reason ethnic minorities were subjected to such camps in minority areas had more to do with their quest for national self-determination/independence than a challenge to the CCP’s bureaucratic socialist line in a general sense—this is what distinguished the minority camps from those targeting Han Chinese populations. Mongolian scholar Yang Haiying points out that during the Anti-Rightist campaign, a large number of Uyghur cadres were labeled as “rejecting the Han and sabotaging national solidarity” because of their “historical pursuit of ‘national self-determination’”.11 According to official CCP records, 1,612 people were classified as “rightist local nationalists” in “Xinjiang” at the time.12 Although there is little information available about whether all of these individuals were subjected to forced labor along the lines of “re-education-through-labor”, this seems likely considering the criteria used to sentence Hamuti Yaoludaxifu (an official who had been labeled as a “rightist”) to be “sent down for training through labor (laodong duanlian)” (下放劳动锻炼).13 Similar sentences were assigned during the Cultural Revolution. For example, Söyüngül Chanisheff, a Tatar Muslim from “Xinjiang,” was sentenced to three years of “reform through labor” (laogai) for her involvement in the formation of the East Turkestan People’s Revolutionary Party in the late 1960s.14 Although the system of “re-education through labor” (laojiao 劳教) was officially abolished in 2013 after nearly 56 years, forced labor has not ceased, either in “Xinjiang” or in China proper (内地).15 In contrast with the forced labor system in China proper, however, the one in “Xinjiang” has always been characterized by (internal) colonialism.

After 2014, the system of forced labor in “Xinjiang” began to be highly “ethnicized” (民族化) and evolve into a system of re-education camps in conjunction with the narrative of the “People’s War on Terror”.16 According to statistics, at least 1.5 million Turkic Muslims were imprisoned in re-education camps [as of 2019].17 In parallel with the construction of re-education camps was the development of the textile and garment industry in “Xinjiang,” which accelerated in 2014 to attract industrial transfer from the eastern seaboard and was expected to provide one million jobs.18 With the expansion of “re-education camps” in 2017-2018, the government renamed them “vocational skills education and training centers”, and has been using them as a local economic vehicle for subsidizing companies from China proper to open factories in “Xinjiang.”19 These affiliated factories were built in or near the re-education camps, becoming an extension of the camp system. Many Uyghurs have been transferred directly to the factories after completing their “re-education” period. In 2018, 100,000 detainees were transferred to industrial parks in the Kashgar region alone.20 However, the move from re-education camps to affiliated factories does not mean freedom, but rather harsh exploitation. According to the anthropologist Darren Byler, who interviewed one of the detainees transferred to a factory, her “internship” salary was only 600 yuan per month (one third of the national minimum wage), with various deductions, and she was not allowed to leave the factory, being kept under constant surveillance. In her words, “It was like slavery.”21

Forced labor outside of concentration camps/prisons

Forced labor exists outside of the prisons/camps as well, whether for Palestinians or for Uyghurs. Many of the victims come from the most vulnerable segment of society: nongmin (农民)—ruralites, “peasants”, or people from rural areas.22 In Employing the Enemy: The Story of Palestinian Labourers on Israeli Settlements, Matthew Vickery points out that there are many rural Palestinians living in the “Seam Zone”23 of the West Bank who, due to Israel’s gradual expropriation of their farmland, as well as restrictions on movement and a clampdown on the local economy, end up having to migrate to Israeli settlements to work in the bottom tier of the labor market. These jobs are often as construction workers, agricultural laborers, or salesclerks: overworked, earning less than the minimum wage, required to work unpaid overtime, and lacking social security. Palestinian women workers are in an even more difficult situation than their male counterparts, with even lower wages, more reproductive labor, and often facing sexual harassment by their Israeli employers. Although Palestinian migrant workers are not directly coerced like their incarcerated counterparts, Vickery describes this seemingly “voluntary choice” of exploitation as a more insidious form of “state-instigated forced labor”—because there is no other choice.

In “Xinjiang” since the “Reform and Opening” [a set of state policies launched in 1978, corresponding to a key phase of China’s capitalist transition], the structure of exploitation of rural Uyghurs has been extremely similar. For Uyghurs from rural areas, land dispossession brought about by marketization and urbanization has greatly exacerbated their extreme poverty. Combined with factors such as differences of language, culture and religious practices, serious ethnic discrimination, and restrictions on free movement, in order to make a living, most rural Uyghurs have had to migrate, whether “spontaneously” within “Xinjiang” (as agrarian laborers or to enter low-end non-agricultural industries) or through the government’s mandatory “transfer of labor”. In either case, they have had to face extreme exploitation and oppression involving ethnic discrimination, social segregation, harsh treatment, lack of security, and loss of rights. They have thus similarly become victims of “state-instigated forced labor”. In this section, I compare rural Palestinians in the West Bank since the Israeli occupation with Uyghur ruralites since the Reform and Opening, presenting the structural similarities and differences in the forced labor they have been subjected to outside the camps.

I. Appropriation and Dispossession of Indigenous Land

Forced labor has often been accompanied by the dispossession of indigenous people’s land. This is fatal for rural populations, as land had been the means of production on which their livelihood depended.

In the case of rural Palestinians in the Seam Zone, Vickery uses the example of a village called Al-Walaja to expose in detail how the Israeli colonizers have been encroaching on their land step by step.24 After the Palestinian Nakba (“Disaster”) in 1948, when the villagers were forced to flee their homes, at first they thought the war would be over soon, so they moved to a place nearby the village in order to continue farming their land. After the Six Day War in 1967,25 however, Israel quickly annexed the West Bank. It established outposts, houses for settlers, and a network of roads connecting Israel to the West Bank running through and around the village. Then, in 2002, after the Second Intifada, Israel’s border wall enclosed the village within “Area C” under direct Israeli control. Even the residents’ newly built villages and recently cultivated farmland were incorporated into Israel’s nature reserves under the pretext of “land conservation”. As a result, Palestinian villagers were completely deprived of their arable land and their traditional means of livelihood. In addition, Israel provided incentives for businesses and factories to open in the Jewish settlements. When this was coupled with the restrictions imposed by Israel (discussed in the next section), rural Palestinians were eventually forced to accept jobs working on the settlements for the colonizers. While accepting such jobs is considered illegal by the Palestinian Authority, and some of their better-off compatriots regard the workers as colonial lackeys, many of the workers themselves have also expressed disgust about having to stoop this low.

In comparison, Han occupation and dispossession of indigenous land in “Xinjiang” has been accomplished through both (para-)military occupation and capital enclosure. As early as 1954, the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, a Han-dominated paramilitary entity, was established. The Corps was initially based primarily in Dzungaria [the northern half of Xinjiang], where it reclaimed land and seized water while accepting large numbers of Han settlers.26 For this reason, Uyghur scholar Ilham Tohti has compared the Corps directly to the Israeli settlements in Palestine.27 According to statistics, between 1954 and 1966, the Corps expanded the region’s land under cultivation from 80,000 hectares to 810,000, and the Corp’s population grew from 180,000 to 1,490,000.28 After the Reform and Opening, bureaucratic capitalism replaced bureaucratic socialism29, and the “Household Responsibility System” [where villages were required to divide collectively-owned farmland and allot its use-rights to households] (土地承包制) was introduced to “Xinjiang”. In addition, the central government launched its “Western Development” (西部开发) policy [in phases throughout the 2000s], which vigorously developed “black and white” industries in the region: oil and cotton. With the improvement of the transportation network, many Han were encouraged by the policy to bring money from China proper to the south of “Xinjiang” to rent (承包) large tracts of land and bring it under cultivation, mainly for growing cotton. According to Han scholar Li Xiaoxia, although rural Uyghurs also farmed, they either did not have the funds to rent and reclaim land on such a large scale, or were unable to do so because of the burdensome corvée (义务工) system [i.e. mandatory labor for the local state on public works projects, known by Uyghurs as] hashar.30 By contrast, Han ruralites can be exempted from corvée by paying money, and Han contractors (承包商) can even bribe village cadres to obtain the right to use land (土地承包权).31 In addition, under the bureaucratic system32 of “the five unifieds” (五个统一) [in the early 2000s, during the agrarian phase of Xinjiang’s capitalist transition], local governments exploited smallholding farmers through the designation of planting varieties, low purchasing prices, and various taxes and fees, which greatly reduced the farmers’ agricultural income.33 In the face of such exploitation, rural Uyghurs have tended to become more vulnerable. All of the above have made it difficult for Uyghur ruralites, who lack capital, technology, and social resources, to compete with Han farmers. Eventually, many of them had to contract out their land (at least partially).34 This has led to a large concentration of “Southern Xinjiang’s” land into the hands of local officials and Han contractors. In addition to capital enclosure, as urbanization has progressed in the region, local governments have also expropriated large amounts of land from rural Uyghurs in suburban villages.35 Whatever the specific mechanisms may have been, the expropriation of land has further proletarianized rural Uyghurs who had already been poor to begin with, reducing them to “surplus labor-power from the agrarian and pastoral areas” (农牧区剩余劳动力).

Meanwhile, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the CCP became increasingly wary of “separatism” in “Xinjiang”. Against this backdrop, the large number of unemployed Uyghurs was seen as a destabilizing factor, and employment was urgently needed to stabilize the political situation. In addition, the fast-growing cotton industry in “Xinjiang” and the coastal industries in eastern China also required large numbers of cheap laborers. These factors led the Chinese government to begin a massive transfer of Uyghur “surplus labor-power from agrarian and pastoral areas” to sweatshops in China proper and to cotton factories in “Xinjiang” in the name of “poverty alleviation”. While this program was presented as mitigating the employment problem of ethnic minorities and delivering cheap labor to Han capital, it also served to consolidate the economic colonization of “Xinjiang” by seizing energy and controlling the workforce—thus killing three birds with one stone through the collusion of government and business (官商勾结). The program has been described by Uyghur researcher Nyrola Elimä as a “slave trade.”36 In addition to those Uyghurs whose labor-power is exported by force, others voluntarily look for jobs away from their hometowns. Whether forced or voluntary, however, both face the same highly exploitative employment environment, with the difference being that the former have also been subjected to a certain degree of coercion (even before the advent of the new type of re-education camps). In fact, not all migrant workers (including those who are forcibly transferred) are landless, and landlessness is not a prerequisite for (forced) transfer. But the importance of land cannot be ignored. For those who have land, on the one hand, the government will threaten to confiscate their land to force them to accept the transfer; on the other hand, it is often difficult for them to continue to make a living through traditional farming with a small amount of land under the threat of Han capital. This kind of land dispossession continues to this day, becoming more and more forceful and violent, and more and more intense.37

II. Blocking All Paths of Life

Vickery further dissects that forced labor is not enough to deprive the means of production (land). In order for the colonized to be at the mercy of the colonial power, the latter must also isolate the former from better job opportunities and make them subject only to the dictates of colonial capital. This segregation has both physical and economic dimensions.

(1) Physically, the Imposition of Limits upon the Free Movement of Indigenous Labor-Power

The Israeli colonizers divided the West Bank into Areas A, B and C, with 60 percent of the latter area being directly administered by Israel. Each area consisted of small and large fragmented enclaves that were disconnected from each other. In addition, Israel had built the separation wall and established numerous roadblocks, outposts and checkpoints. This process of land grabbing and fragmentation of indigenous lands and the imposition of apartheid is also known as the “Bantustanization” of Palestine.38 Combined with the fact that many roads are restricted to Israelis and are often closed abruptly by Israel, the cost of transportation for Palestinians from Area C to work in cities in Areas A and B is much higher than in settlements. As Vickery notes: “A talented carpenter in the south of Hebron Hills [in Area C] may fit the bill for a job at a lumberyard in Ramallah, only 26 miles away, but with Israeli restrictions on movement, checkpoints, and the road system, the journey to get there would take hours.”39 Moreover, body searches are often accompanied by humiliation and violence, and personal safety is threatened when conflict erupts. These factors make it difficult for Palestinian farmers in the Seam Zone to work in the cities, and they are forced to look to the settlements for work.

In “Xinjiang”, Uyghur farmers are also restricted in their migration. Uyghur economist Ilham Tohti has analyzed that “the special geographic environment, characterized by closed, isolated oases,” makes it difficult for Uyghurs to move from their main habitat, the remote and underdeveloped rural areas of “Southern Xinjiang,” to the highly industrialized Han settlement known as the “Economic Belt on the Northern Slope of the Tianshan Range” (天山北坡经济带).40 Uyghur scholar Abduweli Yimiti also points out that the long distances, high costs, and poorly constructed roads in the countryside make it harder for rural Uyghurs to migrate to China proper for work than it is for their Han counterparts. In addition to natural geographic factors, there are also social factors such as language barriers, cultural and religious differences, and ethnic discrimination.41 Therefore, although a few Uyghurs with “richer social experience and more social connections” (社会经验较丰富、社会关系较多) have gone out to do business after the mid-1980s and have succeeded in doing so (mainly by opening restaurants and trading), most of the surplus laborers in the Uyghur countryside can only move within “Xinjiang” to work as agricultural laborers, or to work in neighboring towns or large cities, such as Urumqi.42 According to 2001 statistics, there were approximately 1.8 million surplus laborers in the rural areas of “Xinjiang” (about 44% of the local rural labor force), but only 20,000 of them went out to work (only 1% of the rural surplus labor force), and 99% of the transferred laborers worked within “Xinjiang.” This can also be seen in the fact that 99% of the transferred labor force is employed within the “border”.43 This is also evidenced by Wang Lixiong’s account of his 2003 visit to “Xinjiang”: “[Xinjiang’s] Han youth can at least go to China proper to work, while the local ethnic youth can only stay at home. They can only stay at home.”44

After the July 5 incident of 2009, the high-pressure stabilization policy has made it even more difficult to monitor and restrict the movement of Uyghurs: checkpoints on the streets are equally dense; identity cards are linked to ethnicity; permission from the local police is required to travel outside of “Xinjiang”; it is difficult to stay in a hotel or rent a room in China proper; residence registration forms are in Chinese only; it is extremely difficult to obtain a passport, and so on.45 These obstacles make it even more difficult for rural Uyghurs to move around, further exacerbating their unemployment.

(2) Economically, the Strangulation of Independent Indigenous Economies and the Racial/Ethnic Segregation of the Labor Market

In addition to physically restricting the movement of rural Palestinians, Israel uses the building permit system to limit their possibilities for self-development. In Area C (the area of the Seam Zone), Palestinians need Israeli approval to build anything—even a small chicken farm. In reality, the likelihood of obtaining permission is negligible. In 2023, Palestinian applications for building in Area C were rejected at a rate of 95%, while settler applications were overwhelmingly approved.46 Even if one takes the risk of building a small workshop privately, it will be demolished if discovered by the Israelis. As Mohammed, a villager from Alwalaga who works in the settlement, says: “If I had a chance to start my own business, build a project, I would do it. But this is Area [the area of the West Bank under complete Israeli military control]. I can’t create anything.” In addition to restricting the self-development of the original inhabitants, Israel has, through various means, imposed a total economic stranglehold on the areas under the jurisdiction of the Palestinian Authority (Areas A and B.) After the Paris Accords of 1994, the Israeli currency, the shekel, became the main currency of exchange in the West Bank; Israel has full control over the import and export of Palestinian goods; and even the Palestinian Authority’s tax revenues are collected under Israel’s responsibility. This all-encompassing stranglehold has made it difficult for the Palestinian urban economy to grow healthily, and the labor market naturally has seen supply far outstrip demand. As a result, the high unemployment rate has discouraged Palestinian farmers from moving to the cities.

In the rural areas of “Xinjiang”, as mentioned earlier, not only to Uyghur farmers lack any control or competitiveness in agricultural production, they even have to give away their land. In the energy sector, the enormous power and lucrative profits from local oil and gas development are even more firmly held in the hands of the Han bureaucracy, and the Uyghurs are not allowed to get their hands on any of it. According to statistics, the “West-East Gas Pipeline” project alone provides the “Xinjiang” government with more than one billion yuan in tax revenues each year.47 If these resources were autonomously developed by Uyghur farmers and workers in a democratic manner, they might be able to solve their employment problems more efficiently and develop their economy more equally, and at the same time avoid the environmental damage caused by over-exploitation by Han capitalists, and would not have to “rely” on so-called ” poverty alleviation” projects or gather in low-income sectors. In addition, the Uyghur bourgeoisie, which could have provided some impetus to the development of [an independent Uyghur] “ethnic economy” (民族经济) and job opportunities for compatriots, has been subjected to a long history of repression: many entrepreneurs have either been arrested, as in the case of Rebiya Kadeer, or have had their property confiscated.48 Moderate intellectuals such as Tohti have been heavily silenced and even imprisoned. As a result, Uyghurs’ attempts to develop an independent economy have become a fool’s errand.

The most crucial aspect is the strict division of the labor market according to race/ethnicity. In the case of Israeli colonizers, this division was accomplished through the work permit system. In order to work legally in Israel or in Israeli settlements, Palestinian workers must first obtain a work permit approved by Israel. The work permit system also limits Palestinian workers to agriculture, construction and services. Most of these industries have poor working conditions and low pay, making it difficult to recruit Israeli Jews. Meanwhile, the management of businesses is dominated by settlers. The situation in “Xinjiang” is strikingly similar. Despite the fact that Chinese law stipulates that ethnic minorities should enjoy fair employment rights, almost every industry advertises “Han only” (and Uyghurs earn less than Han workers even if they are in the same industry).49 This is true for the government, the Corps, state-owned enterprises, and private companies. High-tech, industrial, and energy industries exclude Uyghurs. This leaves Uyghurs traveling from the south to the big cities in the north the single option of looking for work in low-paying sectors such as services and restaurants. It should be emphasized that this ethnic segregation in the labor market has nothing to do with educational attainment. Instead, employment discrimination has led Uyghurs to believe that going to school is useless. According to Tohti, only 15 percent of Uyghur university graduates are employed. In order to find employment, many university students have to work in factories or start small businesses (such as street stalls).50

The same is true in Palestine. Palestine has nearly the highest literacy rate in the world, yet more than half of its university graduates are unemployed.51 And in “Xinjiang”, the doors to upward mobility are closed and ethnic unemployment is high. This has even pushed many Uyghurs into crime. For example, after the 1980s, many Uyghur children were abducted and sold by their peers to become thieves in China proper, and a large number of Uyghurs went to Yunnan to sell drugs.52 This phenomenon, in turn, made the uninformed Han in China proper resentful of Uyghurs, deepening misunderstandings and ethnic conflicts.

It can be seen that the colonial ruling class segregated the labor market by race/ethnicity, whether by means of the work permit system or employment discrimination. As Vickery argues, the labor market was divided by race/ethnicity into a primary labor market and a secondary labor market: the primary labor market (high-income industries and high-level jobs) was reserved for the colonizers (Jewish/Han settlers), and the secondary labor market (low-income industries and bottom-level jobs) was reserved for the colonized (Palestinians/Uyghurs).[53] This is why Tohti says that the urban-rural dichotomy in China proper is equivalent to the Han-Uyghur dichotomy in “Xinjiang.”

In a nutshell, whether it is Israel or the CCP, the colonial ruling class, by depriving the indigenous people of their land and blocking all ways out, has proletarianized the colonized ethnic group53 and ultimately forced it to be “voluntarily” slaughtered by colonial capital. In this extreme case, even without direct coercion from the state apparatus, the colonized people have no choice but to survive. Thus, rural Palestinians and Uyghurs essentially share the same conditions of being forced to work. The intensification of ethnic tensions caused by prolonged settler colonization and ethnic segregation has led Uyghur and Han scholars to compare “Xinjiang” to Palestine and South Africa.54

Division and Conquest to Break Resistance

Forced labor and economic subjugation have not only provided a constant source of fuel for colonial capital accumulation, but have also divided the colonized and undermined collective resistance. In both Palestine and “Xinjiang,” the large population of unemployed people constitute what Marx called an “industrial reserve army” — a reservoir of cheap labor-power. In the case of Israel, this reservoir includes not only unemployed Palestinians, but also migrant workers from other countries. In order to earn a living and support their families, indigenous proletarians had to enter the secondary labor market planned by the colonizers essentially as serfs or slaves, even though it was highly exploitative. Once employed, they joined the active labor force in opposition to the industrial reserve army, in constant fear of losing their jobs. Both they and the capitalists knew that there were many unemployed people who desperately needed the job. Thus, on the one hand, colonial capitalists are free to rip off the employed indigenous workers, while on the other hand, the workers are forced to accept the rip-off for fear of being replaced. In this way, the confrontation between the colonizers/bourgeoisie and the colonized/proletariat is transformed into a confrontation between the active labor force and the industrial reserve army — that is, a confrontation within the colonized proletariat. Under these circumstances, any resistance, whether from the workers themselves or their fellow Palestinians/Uyghurs, will make it difficult for them to keep their jobs.

For example, Palestinian workers in Gaza and the West Bank who have tried to unionize or sue their employers have been at high risk of losing their jobs, and have even been blacklisted from ever working in Israel again. And the collective punishment of ethnic resistance is most evident in today’s genocidal war. Thousands of Palestinian workers have been forcibly repatriated to Gaza since the war broke out on October 7th of last year. Up to 200,000 Palestinian construction workers have been barred from traveling to work in settlements in the West Bank.55 Even Palestinians who remain in Gaza and non-settlement portions of the West Bank to work have not been spared: some 400,000 Palestinians have lost their jobs as a result of the war.56 In addition, Israel has withheld up to $78 million of monthly tax revenues from the Palestinian Authority, making it impossible to pay public employees..57 In the face of labor shortages created by collective punishment, Israel makes up for them through the importation of migrant workers from other countries. According to statistics, [last year] 10,000 Indian workers [were expected to] come to Israel to fill labor gaps in the Israeli construction industry.58 The reason why Indian workers are willing to take the risk of going to Israel is precisely because of the current severe employment crisis in India. In fact, since the first Palestinian Intifada, Israel has been importing migrant workers from other countries, including China, to replace Palestinian construction workers — with no guarantees of basic rights.59 All of this is done to protect Israel’s “national security” and to prevent Palestinian workers from taking advantage of Israel’s dependence on their labor to form an effective movement against apartheid — as black workers once did in South Africa.

This collective punishment of resistance also applies to Uyghur workers. According to Mehmet Emin Hazret, after the 1997 “Yining Incident” of February 5th in 1997, a large number of factories and enterprises in Ghulja (so-called “Yining”) “closed down” and sacked many Uyghur workers on the grounds of “bankruptcy,” “lack of demand,” and so on. At the same time, however, most of these factories (or factory plots) were sold to Han settlers, and Han workers ended up with better conditions than their Uyghur counterparts. In the case of the Construction Bureau of Ili Prefecture, for example, “there were more than 1,000 employees, 90 percent of whom were Uyghurs. The Uyghur employees’ jobs were eliminated through the process of privatization after the incident. The owner who contracted the enterprise brought more than 10,000 Han workers from China proper in order to complete the projects that he had taken over from corrupt officials. These workers now work in Ghulja and the surrounding areas. None of the Uyghurs, who were willing to take even the worst jobs to support their families, have been hired back.”60 The reasons for the dismissal of the Uyghur workers and the recruitment of Han workers to replace them can be easily imagined.

On the other hand, the polarization of the Uyghur proletariat is brutally hidden in the re-education camps and their satellite factories. As Byler reveals, while there is severe repression in both places, conditions in the satellite factories are relatively better (e.g., there is less security surveillance, and workers still have some degree of freedom of movement). Uyghur workers in the factories have thus become active labor army.61 The large number of detainees in the re-education camps serve as a reserve labor army. Thus, factory workers needed to prove that they were industrial workers who had “truly completed their re-education” through absolute obedience. For both capitalists and workers knew that “any complaints, any slowdown in production, could result in their [the workers’] replacement with other detainees.”62

One might wonder if there is a possibility of interracial/-ethnic class struggle since Jewish/Han workers and Palestinian/Uyghur workers are all oppressed by the same ruling class. But experience tells us this would be very difficult. Historically, British and Irish workers, and white and black workers in the US and South Africa, have been in hostile camps. This is because the bourgeoisie not only divides the colonially racialized/ethnicized proletariat from within, but also divides the proletariat of the colonizing and colonized “races”/ethnic groups. There is a “you versus me” precisely because the exploitation of the “you” favors the “me”.

In the West Bank, for example, nearly two-thirds of Israeli settlers (overwhelmingly Jewish) come to “improve their quality of life” via low housing prices and high subsidies.63 According to statistics, the average house price in Tel Aviv in 2013 was $600,000, while the average house price in Ariel (the 4th largest settlement city in the West Bank) was less than half of that!64 Due to the low housing prices in West Bank settlements, even many Israeli Palestinians have come to buy homes here.65 Teachers who come to work in the settlements also receive a 20% salary increase, and government subsidies cover 80% of housing rent and 75% of travel expenses.66 The same is true in “Xinjiang”. For example, the government subsidizes businesses to encourage their entry into the region. In recent years, the Corps has also encouraged Han proletarians to relocate to “Xinjiang” by providing new immigrants with housing, jobs, and land.67 These policies are often aimed at college graduates looking for jobs, migrant workers, the unemployed, and laborers who have been lifted out of poverty — “surplus labor-power” excluded from the competitive national/urban labor market.68 (Here it should be noted that the largest influx of Han settlers into “Xinjiang” in the first three decades of the CCP’s rule was not organized by the Corps, but consisted of over 2 million people who were fleeing the [Great Leap] Famine [1959-1961].69)

Add to this the fact that the racially/ethnically segregated labor market was already favorable to Jewish/Han workers. It can be seen that both Israeli and Han settlers, for the most part, were promised upward mobility and relatively favorable economic conditions by the colonial system. In their article “Xinjiang, Capital, and Ethnic Oppression,” Yu Zhou also compares Han settlers in the region to W.E.B. Du Bois’s White Americans. Yu Zhou acutely pointed out that in addition to economic benefits, Han immigrants also received “spiritual rewards” from ethnic oppression: social respect.70 Similarly, even the lowest stratum of Jewish Israeli enjoys “the civil and human rights, the land, the home, the social benefits of which the Palestinians are denied.”71 Under racial/ethnic segregation, racial/ethnic identity itself is a great privilege. Personal morality aside, why would proletarian settlers reject a system that has all the advantages and none of the disadvantages for them? It’s as hard as asking the privileged cis straight male to oppose the patriarchy. No wonder the Israeli socialists Moshe Machover and Akiva Orr say that it is material reality that prevents proletarian class solidarity between Palestinians and Jewish Israelis.73 Nor was this an isolated case. According to a 2011 opinion poll by UighurBiz, “The vast majority of Han interviewees support a hardline policy toward Uyghurs. 89.4 percent of the Han interviewees in Xinjiang wanted to maintain and strengthen Han dominance at all levels. 82.3 percent of the Han with hukou [household registration] based in Xinjiang supported the continuation of exclusive control.” Data is the best evidence.74

In a more sinister type of social division, the colonial ruling class also cooperates with some of the colonized people, making partial concessions and incorporating them as agents to discipline their compatriots. The most notorious example is the Palestinian Authority, a puppet regime that helps Israel suppress the Palestinian people. Also, Palestinian middlemen in the labor market are part of the system of oppression. Vickery points out that Palestinian workers in the West Bank rely heavily on intermediaries of the same ethnicity in order to obtain work permits. These intermediaries are mostly Hebrew-speaking Palestinians from higher social strata. They are well-connected and able to better communicate with Israeli employers. However, instead of fighting for the legal rights of Palestinian workers, they often become accomplices of Israeli capitalists in their quest for profit, helping them to leverage legal loopholes, and exploiting and even abusing their fellow workers. In “Xinjiang”, the Han ruling class has also integrated some ethnic minorities into the state apparatus. For example, in re-education camps there are Uyghur and Kazakh guards who watch over their compatriots. According to Uyghur activists Tahir Imin and Dilxat Raxit, such individuals can be broadly categorized into three groups: (1) “typical degenerate ethnic traitors”; (2) those who have no choice but to do so for their own safety and that of their families; and (3) those who are unable to find good jobs.75 They were all promised some reward by the colonial rulers: either means of subsistence or personal freedom. But in any case, they were victims of inhuman forced labor, perpetual “two-faced people” (两面人)76—and it seems likely that this is where much of the so-called “degeneration” comes from.

Concluding Remarks

Decades of Palestinian and Uyghur suffering have taught us the isomorphism (同构性) of oppression. While the dictatorship of the CCP is vile, the incompetence and hypocrisy of bourgeois democracy is also evident in Israel, which is also guilty of genocide, as well as in its Western imperialist allies, who provide it with a protective umbrella of arms and money. At a time when Palestinians and Uyghurs are suffering genocide together, and when black prisoners are being subjected to forced labor in American prisons,77 we must understand that there is no meaningful difference between Chinese dictatorship capitalism and liberal democratic capitalism. Not to mention that international law is a sham on the issue of Israel and Palestine, and the double standards of human rights are disgusting: even the freedoms of speech and protest, most basic in liberal democracies, are severely eroded, and the already limited bourgeois democracy is reduced to a police state. The root cause of this similarity in oppression is none other than isomorphic capitalism.

Thus, the overthrow of dictatorships and the achievement of national/ethnic self-determination are essential, but not sufficient, for anti-colonial politics. In colonies where the interests of capitalists and settlers are intertwined, the colonized “race”/ethnic group is almost universally proletarianized. Even after decolonization is completed, the indigenous people still have to deal with foreign capital, which is always on the prowl. With the globalization of capital, it is difficult to develop an indigenous economy without opening up markets. Therefore, even after the abolition of apartheid and the advent of bourgeois democracy, the existing or new indigenous/ethnic bourgeoisie will inevitably embrace foreign capital and continue to exploit their proletarian compatriots — just as in the United States and South Africa today. In other words, even if military occupation and settler colonization are eliminated, capital will be able to reorganize itself and carry out economic colonization. At that time, capital may not be “Chinese” or “Israeli”, but it will always be capitalist. Therefore, we must recognize the material reality of a racially/ethnically divided proletariat and uproot the capitalist system that reproduces colonial structures. At the same time, we must avoid repeating the mistakes of the CCP’s phony institutions of “national autonomy” and build a genuine socialist democracy based on the principle of genuine national/ethnic self-determination. Only then can we put an end to racial/ethnic oppression and achieve freedom and equality, leading to the liberation of all.

- See “Misery and Debt: On the Logic and of Surplus Populations and Surplus Capital”, Endnotes 2 (2010); Chinese translation forthcoming in 既非先知也非孤儿:《尾注》选译.

- Even the notoriously pro-Western Christian fundamentalist Adrian Zenz admits such a shift has taken place in this article/report written for state-backed US propaganda outlet Radio Free Asia.

- For more interesting insights into the global actions for Gaza, also see the recent interviews by Endnotes and Megaphone with participants in the US university encampments, which were also discussed at some of these events in China.

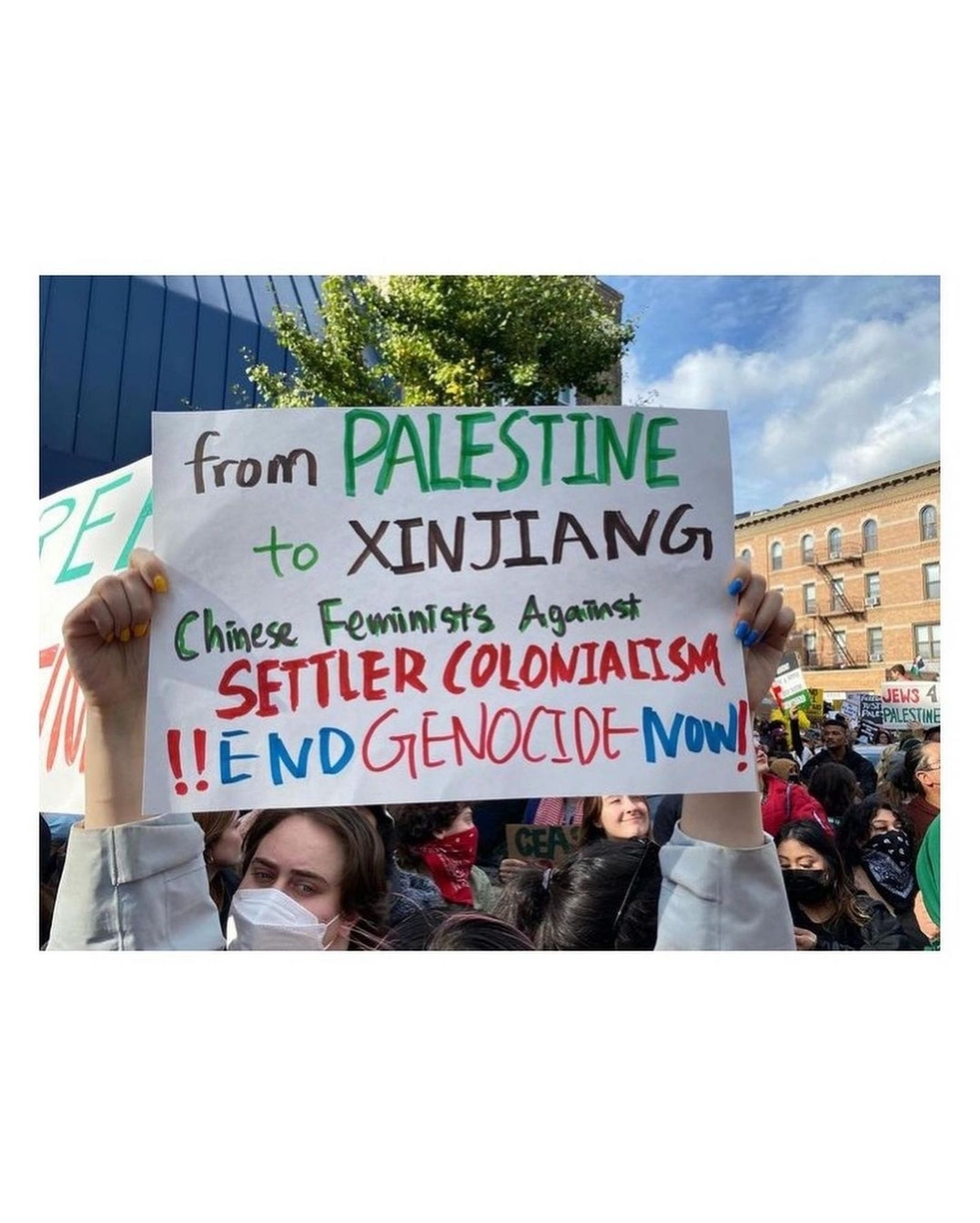

- This article was originally published on Matters (May 22, 2024) as 从巴勒斯坦到“新疆”: 强迫劳动和资本统治. Note that the author puts “Xinjiang” in scare quotes to indicate the colonial imposition of this name (originally by the Manchu-ruled Qing state in the 19th century), in contrast with local Turkic designations such as “East Turkestan.” Header image from Uyghur Truth Project. Please note that our use of this beautiful image does not imply endorsement of any form of nationalism. As Canyu’s final paragraph suggests, the working class has no nation, and the liberation of humankind from the rule of capital could only come about through our cross-border alliance against all states — which are merely “a committee for managing the common affairs of the bourgeoisie as a whole.” –Translators.

- Hasbara refers to the grand outreach used by Israel to control public opinion and whitewash itself.

- The term “tankie” usually refers to Western leftists (e.g., Stalinists, Maoists) who support authoritarian regimes in self-styled “socialist countries”. These people tend to believe that the Western powers (especially the United States) are the only imperialist forces (and therefore any anti-Western stance is justified), while ignoring the imperialist practices of non-Western countries (e.g., China, Russia) and the oppression of their own people. {Translators’ note: The term “tankie” was originally coined by dissident Marxists in the UK to criticize those who continued to support the USSR after its use of tanks to suppress the 1956 uprising in Hungary. It is therefore somewhat ironic that the term has now become associated with support for even regimes such as the PRC that have explicitly rejected such historical “socialist” experiments as “leftist errors,” embraced the global market as part of an “initial phase of socialist construction” expected to last hundreds of years before anything resembling communist transition could be considered again, invited private capitalists into the party as “entrepreneurial workers,” and asserted a material position central the planetary system of capitalist production. For clarification, see our FAQs “Is China a Socialist Country?” and “Is China a Capitalist Country?”}

- There is also small faction of Chinese liberals who support both Palestinians and Uyghurs, whom I would categorize as “left-leaning liberals” (左倾自由派 or 自由左翼, as some of them self-identify), as opposed to the right-leaning majority of Chinese liberals. Based on my personal interactions and observations, left-leaning liberals can be roughly divided into three overlapping groups: (a) “elites” who are already familiar with the history of Palestine, or who are otherwise more educated, enabling them to access information in English to grasp both sides of the story; (b) grassroots activists with less access to this information, but who remain highly alert to and critical of all forms of oppression based on their belief in universal human rights; and (c) feminist and queer left-leaning liberals with an awareness of the intersectionality of gender, race, class, etc. Although left-leaning liberals consistently criticize the genocide of Palestinians and Uyghurs from a humanistic perspective, they typically do not adopt a Marxian viewpoint of class struggle, and they often pay less attention to the capitalist and imperialist forces behind colonizations, as well as the overall history of the Global North’s exploitation and oppression of Global South. Regardless, almost all Chinese liberals do not trust Chinese domestic media (which only partially reports about the situation of Palestinians and completely censors the issues of Uyghurs), considering it all to be state propaganda. Instead, they heavily rely on mainstream Western media or independent liberal Chinese media, which makes it difficult for them to critically reflect on their pro-Western positions. Since some Chinese liberals, whom I consider to have a firm stance on the principles of human rights, are still misguided by Zionist propaganda due to their lack of access to more comprehensive information, I use the broader term “liberals” to label this set of groups as a whole, rather than specifying “right-leaning liberals.”

- Yazan al-Saadi “On Israel’s Little-known Concentration and Labor Camps in 1948-1955“, 2014.

- Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association, “The Economic Exploitation of Palestinian Prisoners“, 2016.

- Ralph Schoenman, The Hidden History of Zionism, 1988.

- Yang Haiying (杨海英), ‘The Cultural Revolution of the Uyghurs’ (维吾尔人的文革), Southern Mongolian Comment on Current Affairs (南蒙古时事评论), May 2020.

- According to Jun Kumakura’s (熊仓润) book Xinjiang: Seventy Years of CCP Domination (新疆: 被中共支配的七十年), most of these Uyghur cadres were “pro-Soviet elements” who had defected to the CCP from the former East Turkestan Republic. Resenting the centralized rule of the Han, their aspirations for national self-determination were often influenced by the Soviet Union’s federalism, according to which model they hoped to establish an autonomous republic of Uyghuristan within the PRC, with foreign affairs and the military under the authority of the central government, but with an army made up of local ethnic groups. In fact, before the founding of the CCP, it had supported the “Three Districts Revolution” (三区革命) against Guomindang (KMT) rule, and had written letters in support of the East Turkestan Independence Movement. Even after the CCP seized power in 1949, the “Three Districts Revolution” was recognized as part of the democratic revolution in the CCP’s historical narrative. The former commitment made it only natural, and not radical, for Uyghur cadres to make these claims during the period of Sino-Soviet friendship. Hamuti Yaoludaxifu (哈木提·尧鲁达西甫), discussed below, also noted that “Xinjiang could build socialism without the Han.” This suggests that these Uyghur cadres were not opposed to socialism or communism, but rather to Han rule, whether it be that of the CCP or the KMT. {Translators: We have been unable to find the romanized Uyghur spelling of Hamuti Yaoludaxifu, so have used the romanized Chinese spelling. The “Three Districts Revolution” was the Chinese term for the 1944 Ili Rebellion, led by pro-USSR Uyghurs against the Republic of China, which established the Second Eastern Turkestan Republic until it collapsed in 1947, with the Three Districts remaining independent until they were folded into the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region under the newly established PRC in 1949-1950. The “Three Districts” referred to Ili, Tarbagatay and Altay. See James Millward, Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang (London: Hurst, 2021), pages 211-230.}

- “CCP Committee of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Approves Dismissal of Rightist Hamuti Yaoludaxifu from the Party” (中共新疆维吾尔自治区委员会批准开除右派分子哈木提尧鲁达西甫的党籍), 1959, Banned Historical Archives (和谐历史档案馆).

- A party named East Turkestan People’s Revolutionary Party (东突人民革命党) was established in 1946 and dissolved in 1948. In 1967, a new party was formed under the same name. For details see Qurban Niyaz, “I Lived My Life as I’d Said I Would, I Have no Regrets’: Former Xinjiang Independence Activist” (RFA, 2020), and “China/Uighurs (1949-present)”.

- According to the Foundation for the Study of Reform through Labor (劳改研究基金会), between 40 and 50 million Chinese are subjected to forced labor. Outside of “Xinjiang”, Han Chinese and Taiwanese political prisoners are also subjected to forced labor. For example, in recent years, political prisoners such as Guo Feixiong, Li Mingzhe (Taiwan), Cheng Yuan, and Ou Biaofeng have all been subjected to forced labor in prison. {Translators: The laogai (reform-through-labor) system has not been officially abolished and is still used for certain types of political prisoners. The term translated here as “re-education camp” (再教育营) was apparently not an official term, but was used colloquially for the “re-education-through-labor” (laojiao 劳教) system that existed from the 1950s until its formal abolition in 2013 as a sentence for minor criminal offenses. Since then, convicts with similar charges have been sentenced to either regular prisons (监狱), psychiatric hospitals, or addiction rehabilitation facilities, all of which have been known to require inmates to work. This is especially true for ordinary prisons, which function similarly to prisons in other countries (including those in Israel/Palestine mentioned above), requiring prisoners to earn wages (far below minimum wage) in order to purchase necessities through the commissary. In contrast with some of those countries, however, the prisoners seem to have less choice over whether to participate (being exempted only for health reasons), and the goods produced are sold directly on the market. One friend we interviewed, who was sentenced to three years in prison from 2019 to 2022 (for selling marijuana), was required to work in a prison factory producing tents for commercial use. He noted ironically, however, that the conditions and hours were not as bad as those of conventional factories outside the prison.}

- Translators: It appears to be only in Xinjiang (and not even in Tibet) that, after the formal abolition of the laojiao (“re-education through labor”) system in 2013, a new type of labor camp emerged in 2014 under the name “transformation through education centers” (教育转化中心), until they were renamed “vocational skill education and training centers” (职业技能教育培训中心) in 2017. This new type of camp was focused on a specific type of indoctrination against “religious extremism”, in addition to both the traditional requirement to perform labor and arguably a new component of actual “vocational training” with both technical and ideological components, aiming to transform potentially dissident Turkic Muslim “peasants” into compliant industrial workers.

- Reuters, “1.5 million Muslims could be detained in China’s Xinjiang – academic“, 2019. {Translators: Note that 1.5 million has been the maximum estimate (about one out of every six Turkic Muslims in the region), deduced from “satellite images, public spending on detention facilities and witness accounts of overcrowded facilities and missing family members”, which even the quoted source Adrian Zenz acknowledged to be “speculative.” Our caveat here is meant not to minimize the atrocities, but merely to strive for factual transparency, and to expand the scope of analysis beyond labor camps as such. As noted in our preface, the PRC’s strategy against Turkic Muslims seems to have shifted since this 2019 high point of detention in “vocational training facilities” toward transferring detainees into ordinary prisons or releasing them back into society, and then compelling compliance with state policies and the production of surplus-value in other ways—including relocation to ordinary factories in Xinjiang and China proper.}

- Xinjiang Daily (新疆日报) “Xinjiang Accelerates Textile and Garment Industry Development in the Next 10 Years” (未来10年新疆加快推进纺织服装产业发展), 2014.

- See Darren Byler, In The Camps: China’s High-Tech Penal Colony (Columbia Global Reports, 2021); Chinese version available for free on Chuangcn.org/books.

- Government Information Public Platform of Kashgar (喀什政府信息公开平台), “Announcement on the Issuance of the Implementation Program of Employment Training for Disadvantaged Groups in the Kashgar Region” (关于印发《喀什地区困难群体就业培训工作实施方案》的通知), 2018.

- Byler {page 113 of English book, 116 of Chinese PDF}.

- Translators: See “Gleaning the Welfare Fields: Rural Struggles in China since 1959” in Chuang 1 (2015) for our analysis of the category nongmin and its changing material referent during China’s capitalist transition. We are less familiar with the situation in Palestine, but in translating this Chinese term, we stick with “ruralites” or simply “rural Palestinians/Uyghurs” since it could be applied to anyone born and based in the countryside, despite their degree of proletarianization or dependence on money obtained from sources other than farming their own land for use or sale. (“Peasant” and “farmer” both imply a greater degree of independence from such income. “Rural resident” implies actually living in their villages most of the time, which is not the case for most young Chinese ruralites or the Palestinians who lost their land and were forced to work on the settlements—although it did seem to be the condition of many Gazans until last fall.)

- The “Seam Zone” refers to the small buffer zone between Israel’s 1949 ceasefire line and the physical border wall, which is part of Area C of the Israeli-controlled West Bank. According to United Nations figures, approximately 50,000 Palestinians lived there in 2006.

- Matthew Vickery, Employing the Enemy: The Story of Palestinian Labourers on Israeli Settlements (London: Zed Books, 2017)

- The Six-Day War refers to the conflict from June 5th to 10th, 1967, between Israel and a coalition of Arab states centered on Egypt, Syria and Jordan. Israel quickly defeated the Arab coalition in just six days, capturing Palestine’s West Bank, Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, and Syria’s the Golan Heights. The war displaced hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, led to land dispossession and fragmentation, and exacerbated the plight of the Palestinians, with repercussions continuing to this day.

- Laura T. Murphy, Nyrola Elimä, and David Tobin, “Until Nothing is Left: China’s Settler Corporation and its Human Rights Violations in the Uyghur Region—A report on the Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps” (Sheffield Hallam University: Helena Kennedy Centre for International Justice, 2022).

- Ilham Tohti, “Present-Day Ethnic Problems in Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region: Overview and Recommendations” (当前新疆民族问题的现状及建议) {written in 2011, published after Tohti’s arrest in 2014, English translation published on China Change in 2015, where the Chinese is also available.}

- Zhu Peimin (朱培民) and Wang Baoying (王宝英), History of the CCP’s Rule in Xinjiang (中国共产党治理新疆史), 当代中国出版社, 2015.

- Translators: “Bureaucratic capitalism” and “bureaucratic socialism” are categories that we associate with Trotskyist attempts to theorize the USSR and China during the era of state-planned economy. These differ from our own analysis in “Sorghum and Steel” (Chuang journal, issue 1) where we propose the term “socialist developmental regime” to describe China’s unstable “non-mode of production” from 1956 to the 1970s. In “Red Dust” (Chuang 2) we then analyze the transition from this regime to the capitalist mode of production in the 1970s-1990s, noting that the latter mode is fundamentally the same throughout the world—regardless of the political institutions or other national conditions that might make it appear “bureaucratic” or otherwise distinctive on the surface. (This is consistent with Canyu’s discussion of “isomorphic capitalism” at the end of this article.) For a more accessible synopsis, see our FAQs, including “Is China a Socialist Country?”

- Translators: According to Li Xiaoxia’s book cited in the next note, “After the household responsibility system was implemented, collective production was replaced by household production, and villagers worked on their own land individually, with Han and Uyghur villagers working together only when they were doing compulsory labor [i.e. corvée] and in large-scale farmland and water conservancy construction. Later on, however, residents of Han villages have been replacing compulsory labor with money, and Han villagers in mixed villages often do the same. Since the number of Han villagers is relatively small, most of them have the ability to substitute money for compulsory labor, and many Han villagers wish to have more time to make their own production arrangements. This form of substitution for compulsory labor has gradually become an institutional arrangement. According to a survey conducted in 2005 in Gedakul village, Bixibag township, Kuqa county, there were 13 Han households in the village. The village no longer required Han villagers to perform compulsory labor, but rather required them to pay a certain amount of cash based on the amount of land they had contracted.” Li Xiaoxia (李晓霞), Han People in the Rural South of Xinjiang (新疆南部乡村汉人), 社会科学文献出版社 (2015), p. 395. (Thanks to Canyu for pointing this out.)

- Li Xiaoxia (李晓霞), Han People in the Rural South of Xinjiang (新疆南部乡村汉人), 社会科学文献出版社, 2015.

- Translators: The Chinese term used here (官僚计划经济) literally means “bureaucratic planned economy,” but we changed it to “system” because the state-planned economy for China as a whole had already been completely replaced by market mechanisms by this time (the early 2000s), even if the capitalist transition was not yet complete in the agricultural sector until the 2010s. Apparently in Xinjiang, this transition involved a particularly high degree of planning by local governments. In response to our query, the author explains: “What I’m suggesting by this term is that the local governments played a pivotal role in planning what Uyghur farmers to plant in the early 2000s, rather than allowing them to decide themselves. As Tursun {cited in the next note} described it, “After the reform and opening up, the land contracting system was implemented in the rural areas of our country, and the farmers have been operating independently, regulated only by the market economy. In Yeyik Township, however, I learned that while each household had long been allocated at least 15 mu of land, the farmers there were still not able to operate independently. There, the planned economic system still existed, and the whole of agricultural production was still carried out according to the instructions of government agencies.” From my understanding, though the bureaucratic factor might be diminished by market force later, as you elaborated in the footnote, the collusion of governments and enterprises persists.”

- According to Uyghur scholar Baihetiyar Tursun [based on a 2001 survey], the “five unifieds” referred to unified cultivation, unified sowing, unified management, unified irrigation and unified harvesting. His description fully captures [that era’s methods of] agrarian exploitation: “seeds, fertilizers, plastic sheeting, pesticides and so on had to be purchased by the township government and then sold to the farmers at a price determined by the township; the farmers were not allowed to purchase them on their own. If farmers did not have money, they could get a loan from the township credit union (乡信用社). After the summer harvest, the amount that remained after deducting the interest on loans and other expenses was the farmers’ actual income. A village cadre in Yeyik Township (叶亦克乡) gave me this calculation: If a farmer grew 10 mu [0.6 hectares] of wheat, he could earn 4,500-5,000 yuan according to the local harvest standard and grain sales price. But that year’s expenses for plowing, sowing, water, fertilizer, management fees, land tax, village and township funds, and the public welfare fund (公益金) would could about 4,000 yuan. After deducting these expenses, the farmer’s actual income was only 500 to 1,000 yuan.” Baihetiyar Tursun (拜合提亚尔·吐尔逊), “Problems, Countermeasures, and Significance of Socioeconomic Development in Southern Xinjiang: A Field Survey from the South of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (新疆南疆地区社会经济发展面临的问题、对策及其意义 ———新疆维吾尔自治区南疆地区实地调查), Northwest Minorities Research (西北民族研究) 2003(2): 77. {Translators: We inserted additions such as “the agrarian phase of Xinjiang’s capitalist transition” to clarify that these “bureaucratic” mechanisms predominated during an earlier period, which helped create the current structure of agrarian capitalism in Xinjiang—roughly corresponding to the transition in China proper. (As examined in “Red Dust”, China’s capitalist transition as a whole was completed by the early 2000s, but as we will explore in Issue 3, the agrarian transition was not completed until about ten years later.) For example, Tursun’s 2001 survey emphasizes smallholders’ payment of taxes and fees to local government as a key form of exploitation, but such payments were abolished throughout China by 2005. Historically, such expropriation functioned partly to help concentrate farmland into the hands of emerging agricultural enterprises (including some owned by a minority of local farmers, others by non-local firms, and in Xinjiang by the Han settlers discussed here), and to push most ruralites off the land into labor migration—as they could no longer afford the taxes and fees required to use their land. Now, the direct exploiters consist mainly of such (private or state-owned) enterprises operating through a variety of arrangements: former peasants working as laborers on commercial farms that rent land from the village; local smallholders still farming their own land but now under contracts with agricultural firms, etc. (For an overview, see ‘The capitalist transformation of rural China: Evidence from “Agrarian Change in Contemporary China”’, Chuang blog 2015.) On the particular forms through which this transition took place in Xinjiang, see Darren Byler, Terror Capitalism: Uyghur Dispossession and Masculinity in a Chinese City (Duke University Press, 2022), including the passage quoted in the next footnote (which also cites the above passage from Tursun). For a case study of farmland use-right transfers in Kashgar, see Alessandra Cappelletti, Socio-Economic Development in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region: Disparities and Power Struggles in China’s North-West (Palgrave Macmillan, 2020), pages 231-267.}

- Byler, Terror Capitalism. {For example: ‘All these public and private economic interventions produced a new kind of Uyghur farmer. One of the primary goals of the “Open up the Northwest” (Ch: xibei kaifa) state development campaign that began in the 1990s was to increase the production of commodity goods—such as rapeseed, tomatoes, cotton, and other commodity crops—on an industrial scale. …Within just a few short years, many Uyghur farmers were forced to sign debt-inducing contracts that did not meet their basic living expenses or their seed and farming equipment expenses. … As a result, by the early 2000s, in many counties in the Uyghur homeland of Southern Xinjiang, the rights to a high percentage of arable land were owned by a few powerful individuals within local party institutions. For example, according to a number of farmers I interviewed, in a county near Turpan a single individual owned rights to an estimated 60 percent of all available farming land. … Many Uyghur farmers, or their children, were forced to look for work elsewhere either as migrant agricultural workers or as small-scale traders and hired hands in local towns or, at times, the big city of Ürümchi.’ (Pages 107-108)}.

- Li Xiaoxia (李晓霞), “The Process of Rapid Urbanization and the Transformation of Ethnic Residence Patterns in Xinjiang” (新疆快速城市化过程与民族居住格局变迁), Peking University: Department of Sociology (2012), archived on Xinjiang Victims Database.

- Quoted in “The Hostile Environment for Uyghur Workers Uncovered” by Natalia Motorina, Juozapas Bagdonas, Kristiana Nitisa and Mauritza Klingspor, published on Byline Times in August 2021.

- In the 2016 report “Without land, there is no life: Chinese state suppression of Uyghur environmental activism”, the Uyghur Human Rights Project documented cases of land expropriated between 2008 and 2015 and then redistributed or sold to Han settlers. In these cases, compensation was rarely, if ever, paid, and resistance often resulted in police violence or jail time. With the emergence of the new type of re-education camps since the report was written, resistance must have become even more difficult.

- In addition to Vickery, Leila Farsakh, a Palestinian political economist, has detailed this phenomenon in “Palestinian Labor Flows to the Israeli Economy: A Finished Story?” Journal of Palestine Studies 32(1) Autumn 2002.

- Vickery 2017.

- Tohti, “Present-Day Ethnic Problems in Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region.”

- Abduwali Himit (阿布都外力·依米提), “An Analysis of Factors Influencing Labor Migration of Rural Ethnic Minorities and Measures —— with the Example of Uighur Floating Population” (制约少数民族农村劳动力流动因素的分析及其对策), 2007.

- Hanikez Turak (哈尼克孜·吐拉克), “Research on the Survival and Adaptation of Uyghur Migrant Workers in Chinese Cities Outside of Xinjiang: A Case Study of Wuhan” (维吾尔族农民工内地城市生存与适应研究——以武汉市维吾尔族农民工为例), Ethnic Sociological Research Bulletin (民族社会学研究通讯) issue 137, 2013. Also see Byler, Terror Capitalism.

- Himit, “An Analysis of Factors.”

- Wang Lixiong (王力雄), My West China, Your East Turkestan (我的西域,你的东土) {Locus 大塊文化, 2007, available online here}.

- Sam Tynen, “Triple dispossession in northwestern China” {in Xinjiang Year Zero, ANU Press} 2022.

- PeaceNow “The Civil Administration acknowledges extreme discrimination in building permits and law enforcement between Palestinians and settlers“, 2023.

- Xinhua (新华社), “Looking Back at the Eleventh Five-Year Plan, Looking Forward to the Twelfth Five-Year Plan: The West-East Gas Pipeline Project Benefits Both the West and the East” (回眸十一五 展望十二五:西气东输工程惠及西东), 2011.

- Wall Street Journal (Chinese version 华尔街日报), “Once a Bridge of Friendship, Now a Prisoner: The Changing Fate of a Uyghur Merchant” (昔日友好桥梁,今朝阶下之囚——维吾尔族商人的命运转折), 2021; Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Under the Gavel: Evidence of Uyghur-owned Property Seized and Sold Online“, 2021.

- Uyghur Human Rights Project, “Discrimination, Mistreatment and Coercion: Severe Labor Rights Abuses Faced by Uyghurs in China and East Turkestan” (2017).

- Ibid.

- Al-Jazeera, “How Israel has destroyed Gaza’s schools and universities” (2024); The Times of Israel, “Over half of Palestinian college graduates are unemployed, report finds” (2018).

- Phoenix Weekly (凤凰周刊), “I Don’t Want to Be a Thief: A Survey of the Livelihood of Uyghur Street Children in China Outside of Xinjiang” (我不想当小偷——内地维族流浪儿生存调查), 2014; M.Azat, “The Expanding Uyghur Cemetery in Ruili, Yunnan” (正在扩大的云南瑞丽维吾尔人墓地), 2009 {translated from a Uyghur text into Chinese}.

- Vickery, 2017.

- Both Wang Lixiong and Tohti have compared ‘Xinjiang’ to Palestine.

- Reuters “Israel sends thousands of cross-border Palestinian workers back to Gaza“, 2023; The Jerusalem Post “Loss of Palestinian workers at Israeli building sites leaves hole on both sides“, 2024.

- The Guardian “Almost 400,000 Palestinians have lost jobs due to war, report says“, 2023.

- The Times of Israel “PA: Israel held $78 million from monthly tax revenues collected on Ramallah’s behalf“, 2023.

- Business Standard “10,000 Indian workers to reach Israel soon in batches starting next week” 2023.

- The China Project “The Chinese migrant workers who power Israeli construction“, 2020.

- Mehmet Emin Hazret (买买提明·艾孜来提), “The Cost of Unemployment for the Uyghurs of Ili on the Most Fertile Land” (最富饶的土地上的伊犁维吾尔人的下岗代价), {2005, translated from Uyghur into Chinese in} 2009.

- The workers include ‘released’ individuals transferred from re-education camps, as well as ‘surplus rural labor-power’ who had not been detained.

- Byler, In the Camps.

- Israel Policy Forum “West Bank Settlements“; Vox “What are settlements, and why are they such a big deal?” (2023).