In the first issue of our journal, we introduced the 2010 movement to protect East Lake (东湖) in Wuhan as one of China’s only recent cases we’d heard of where urbanites had attempted to articulate a rural land conflict into a broader struggle, which some of the participants understood as anti-capitalist.1 Then in our 2021 book, we translated an interview with members of a collective that had, in some senses, emerged from that movement. Over the past two years we’ve continued to communicate with them and their friends in our research on internationalist left currents in early 21st century China. We’ve learned that the East Lake movement and the Désirée / “Our Home” Autonomous Youth Lab (“我们家”青年自治实验室, 2008-2016)2 that helped give rise to it both played major roles in influencing subsequent developments among China’s anti-authoritarian left in particular, and overlapping activist currents more broadly. As part of our exploration of these trends, then, we’ve decided to present this collection of documents about East Lake, including two newly translated texts and several samples of artwork from the movement, along with related texts previously published here on our blog and elsewhere.3

Future blog posts and a possible book will deal more specifically with Désirée and the ongoing “autonomous spaces” phenomenon partly inspired by it, along with other experiments, struggles and debates that have been redefining China’s small and beleaguered but sometimes vibrant internationalist left over the past two decades.

For convenience in navigating this post, we’ve added links to each section below:

The Battle for East Lake in Wuhan (2010)

The East Lake Art Project: An Overview (new translation, original from 2014)

Mai Dian and Zijie Respond to Mr. Po’s Questions (new translation, original from 2012)

Sample Artwork from the “East Lake for Everyone” Events (new captions, images from 2010-2014)

我们家 : Desiree Social Center : A Liberated Space in Wuhan (2010)

The Battle for East Lake in Wuhan

Slightly modified from the original published on China Study Group in April 2010

Hundreds of Wuhan citizens are fighting to save the city’s East Lake Ecological Tourist Scenic Area (东湖生态旅游风景区) from plans to fill in part of the lake and develop the area commercially.

Villagers and fishery workers evicted by the development have been negotiating with the local government for compensation since December, in the face of physical assault by hired thugs. And last week hundreds of urban residents and students planned a protest march, but this was canceled after police visited the homes of organizers, students were warned against participating by school authorities, and at least one organizer had his internet cut off. Representatives of the development company and the local government held a press conference denying that any part of the lake would be filled and claiming that the development would not hurt the area’s ecosystem, and information to the contrary has been removed from websites. But critics of the plan want to continue the fight and are presently preparing protest activities including a petition and postcards to be sent to the central government, artistic performances, a campaign to pitch tents and camp out at the development site, and a newsletter and internet forum to enable public discussion of the issue.

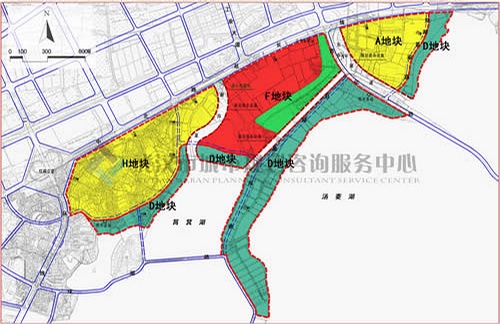

On March 25, the Guangzhou-based newspaper Time Weekly (时代周报) published a report called “An Investigation into OCT’s Development of East Lake in Wuhan” (武汉华侨城开发东湖调查), which disclosed information leaked by government officials disgruntled with corruption in the development proceedings. According to the report, in December 2009 the local government signed a long-term lease with the state-owned real estate development company OCT (Overseas Chinese Town) for 190 hectares (3,167 mu), including 27 hectares (450 mu) of the lake itself, to the tune of 4.3 billion yuan (630 million US dollars) – the most lucrative lease of the year for rapidly-expanding Wuhan. (Land in China cannot be sold and so is leased, usually for 70 years at a time.) This transaction was illegal since much of the leased area falls within the nationally-protected East Lake Scenic Area, and the local government did not obtain permission to develop the land from the central government. Moreover the entire process of negotiation and planning was conducted behind closed doors over several months’ time, without outside appraisal of possible ecological or social consequences. OCT’s plan includes an amusement park (Happy Valley) and upscale shopping areas, hotels and condominiums.

Two villages and a fishery have already been evicted and demolished, starting immediately after the lease was signed last December, and a third village is in the process of eviction. Villagers and fishery workers claim that part of the compensation promised by OCT has been pocketed by government officials, and when they petitioned the government about this they were assaulted by hired thugs. Most of these petitioners have backed down, but about 50 families in the third village are still holding out. All of this went largely unnoticed by Wuhan’s urban population and the news media for three months.

When Time Weekly published its report on March 25, within two hours of its online publication over a thousand comments had been posted about it, according to the author’s blog. The chief concern among online critics of the plan was the possible ecological consequences, since water pollution and algae outbreaks have been increasing rapidly throughout China in recent years, rendering half of China’s population and two-thirds of China’s rural population unable to access safe drinking water, according to some reports. In 2007 an algae outbreak (attributed largely to synthetic fertilizers) in Tai lake on China’s east coast rendered the water undrinkable by two million people in Wuxi. In Wuhan, critics of the East Lake development plan also point to the plight of another local lake, Tangxun. On the 1-to-5 scale of water quality, Tangxun went from 1 to 4 within a decade of development, and experts estimate that even the most concerted effort to reverse the lake’s pollution would take at least another decade just to restore it to level 3.

In addition to concerns about the quality of water for consumption, critics also highlight East Lake’s value as Wuhan’s only body of water safe for swimming now that Tangxun and other lakes have been polluted. One critic ironically points out that only six years ago an environmental expert warned Tangxun might become as polluted as East Lake, whereas now Tangxun has become so toxic that East Lake seems good in comparison!

Finally, critics are concerned about gentrification, as the development plan would transform the lake and its environs from a peaceful, clean place where anyone can enjoy the natural world for free (or a small entrance fee for some of the parks) to an expensive, noisy and artificial resort for the rich. In this sense some commentators emphasize that the effort to protect East Lake differs from recent comparable protests in China since its goal is not to protect private property or relocate environmental pollution farther away from the city, but to prevent public property from privatization.

Critics of the development plan formed an internet group on QQ (China’s most popular social networking service), which soon reached the maximum 100 members per group allowed by QQ and spilled over into several more groups. According to one group manager, although the group was set so that new members must await approval before joining the group, she noticed several new members mysteriously appeared in the group without going through the approval process, and she suspects they were police. Through group discussion the idea emerged of “going for a stroll” (散步), that is, staging a protest march without banners and, when questioned, claiming everyone was “just going for a stroll.” This tactic has been used successfully several times since 2007, when thousands of Xiamen citizens took to the streets against plans to build a chemical plant in the city. (In the Xiamen case most of the mobilization was done via cellular telephone text messaging, but some other protest attempts have been thwarted by police control over the phone networks, and this may be one reason QQ was used in Wuhan.) But last Thursday and Friday police visited the homes of people from the QQ groups and convinced them not to join the protest planned for Saturday. Student counselors (辅导员) at several universities in Wuhan were told, “According to higher authorities, due to the ‘East Lake incident,’ some students are organizing collective marches, creating many unstable factors. In order to strengthen the safe and stable functioning of the school, please strengthen your monitoring of the campus, pay close attention to the students’ tendencies, if you encounter activities such as collective marches, it is imperative to immediately notify the student affairs office.” In the end only a few people showed up for the demonstration, so they decided to call it off.

Internet discussion about the development plan seems to have declined, and organizers blame this partly on a combination of fear of reprisal and state control over the media, with information contrary to OCT’s press statement being removed from the internet. Some activists are trying to remedy this situation by making a newsletter explaining the situation and postcards petitioning the central government, which they plan to distribute by hand throughout the city. In preparation they are conducting research to strengthen their case, including interviews with the evicted East Lake residents and environmental experts. Other activists plan to pitch tents and camp out at the development site, while still others are preparing artistic performances to raise awareness about the issue.4

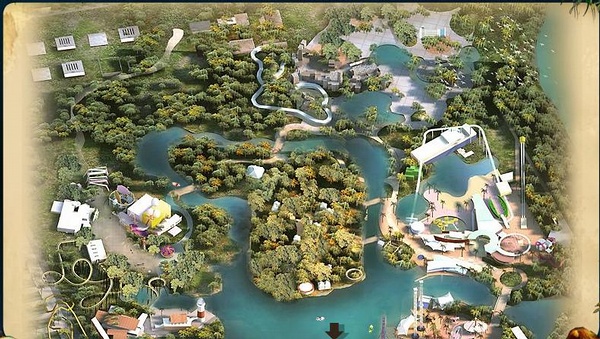

Sketches of what East Lake will look like after redevelopment

The East Lake Art Project: An Overview

Translated from the Chinese original posted on Douban in 2014

The full name of the East Lake Art Project is “East Lake for Everyone” (每个人的东湖). Launched by the Wuhan architect Li Juchuan together with the artist Li Yu in June 2010, the project originated in a “social incident.”

In March of that year, Wuhan residents learned from media reports that the Shenzhen-based [state-owned enterprise] Overseas Chinese Town Group (OCT) had obtained 3,167 mu [190 hectares] of land within and adjacent to Wuhan’s East Lake Scenic Area, where the company planned to build two large-scale theme parks (Happy Valley and a water park), two upscale residential complexes and two resort hotels.[i] Since this development would enclose a large portion of the lake and its shoreline, possibly filling in part of the lake, the plan’s disclosure set off an uproar among the city’s residents. OCT quickly released a statement claiming that the reports were false, saying “The plan’s allocation of land does not encroach upon the surface of East Lake at all,” that it would “not alter an inch of East Lake’s shoreline, nor occupy an inch of the lake’s surface,” and that “there is no plan whatsoever to build hotels in the place of fishponds.”[ii] After this, no further exposés emerged, and the only subsequent reports were positive ones from local Wuhan outlets. Although the blueprints that OCT released through these outlets included large, suspicious blank spots,[iii] and residents who visited the construction sites discovered that the lake was actually being filled in (although work had stopped for the moment), most people believed OCT’s statement. At that time, due to control from multiple angles, it became impossible for any debate about the development to continue.[iv]

Facing this situation, Li Juchuan and Li Yu decided to launch this art project titled “East Lake for Everyone,” hoping that art could be used to open up space for discussion, and to create an opportunity for people concerned about the lake’s future to articulate their voices and express their objections to the development plan. The project was open to everyone, with the two organizers openly recruiting participants online. All the participants were encouraged to visit East Lake and create their own related works of art there, and then to share information about them on a website set up for this purpose. They could choose any time within a designated period, and any location on or alongside the lake. Ultimately, the project lasted two months (from June 25 to August 25, 2010), during which 53 individuals and groups signed up and produced 59 works. The participants came from various walks of life, including artists, architects, designers, punks, musicians, theater workers, poets, academics, computer programmers, self-employed people, unemployed people, teachers, and students. The art sites covered every part of East Lake that could be reached without having to pay an entrance fee.

Late one night during the project, however, on August 5th, the OCT development officially broke ground, including large-scale filling of the lake, with 200 mu of the lake’s surface north of Shaojidou and some of the fishponds from the former East Lake Fish Farm quickly being filled in. One year later, a Happy Valley amusement park appeared atop that section of the lake, followed by a stretch of highrises and luxury condominiums along the shoreline.

In early 2012, as the grand opening of Happy Valley approached, advertisements for OCT’s residential properties began to appear prominently in all kinds of public places throughout Wuhan, and all the newspapers, TV programs and radio broadcasts became dominated by them as well. Whereas two years prior the company had attempted to conceal its true intentions, now OCT bombastically publicized the advantages of its properties’ location, flaunting the amount of shoreline they had occupied. The company’s website, which had denied categorically that a high-end hotel would be built, now shamelessly displayed a 3D map of the “ecological resort platinum five-star hotel” occupying the space that had been left blank in the blueprints OCT had released two years before.[v]

Li Juchuan, Li Yu and others (including Wu Wei, Mai Dian, Gong Jian, Zijie and Yangcai) decided to relaunch the art project on the same day as the grand opening of Happy Valley (April 29, 2012), with this second round titled “Fuck Your Happy Valley.” Participants were encouraged to come create their artworks in the vicinity of the theme park. Whereas the first round’s announcements had avoided directly naming their targets (since those names and related terms had been designated by the authorities as “sensitive keywords”), this time the organizers became more explicit in their wording, resulting immediately in harassment by OCT[vi] and the event’s Douban page being shut down. But the event proceeded as planned, with 33 individuals and groups producing 40 works of art. As before, participants included people from various walks of life, and most of the artworks were created next to Happy Valley, including the square outside the entrance.

In July 2014, a third round took place under the title “Everyone Come and Make Public Art”—ironically referencing real estate companies’ adoption of the term “public art” to appear edgy as they sought to acquire land resources. This round lasted over a month, involving 34 individuals and groups who produced 39 works of art. Around the same time, [a nearby social center called] the Désirée Autonomous Youth Lab hosted 18 related lectures and discussions. The organizers and other participants began to discuss whether this project targeting specific objects, sparked by specific events, should instead become a longer-term project addressing broader issues such as the processes of urbanization today.

Mai Dian and Zijie Respond to Mr. Po’s Questions

Translated from the Chinese original archived on the East Lake Art Project website in 20125

Mr. Po: With regards to the matter of the company OCT (Overseas Chinese Town) filling in the lake, you were the first people to express concern about it and to get involved by investigating and interviewing people, even getting into trouble over it. Could you share some insights on the matter with us? What is happening with the lake area being filled in and what is your understanding of the situation experienced by the villagers living around the lake? Are there any issues in the lake reclamation project that are worthy of particular attention?

Mai Dian: I’m not the first person to get involved and investigate the matter. The first people to research the development project were journalists. We found out that the lake was being filled in because a journalist from Time Weekly, Tao Haiying, wrote a report titled “An Investigation into OCT’s Development of East Lake in Wuhan: 450 Mu [27 hectares]to Be Filled, Fears of Environmental Degradation” (Time Weekly, 25 March 2010). The report described how a company under SASAC (State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council) control not only robbed the “municipal construction” company belonging to the Wuhan government of the “use-rights” to the land, but also took over the “property title” (as the journalist phrased it). Another party was mentioned in the report, the “people who lost their land,” namely the peasants and fishery workers living beside the lake. They were being forced to abandon the land they lived and worked on, so these residents and workers felt that the compensation they received was “unfair.” Aside from the “fears of environmental degradation” in the title of the article, there was barely any mention of how the redevelopment project would affect water quality and the natural landscape in and around East Lake.

The news report triggered objections by a large number of Wuhan residents. To a certain degree these were mostly concerned about environmental degradation. When the latter was referred to in the main body of the article, the wording “filling in the lake” was used, and perhaps it was anticipated that this would fixate public opinion on this specific aspect. The questions of whether the area around the lake should actually be redeveloped and who was benefiting from the project were both of secondary concern. This can perhaps explain the rapid dissolution of dissent. Once OCT’s subsidiary Wuhan Industrial (the developer) published its so-called “refutation of rumors” in the media, their main focus was on arguing the point of whether the water surface they were filling in really belonged to East Lake. After consistently referring to it as “the fishpond” and never as “the lake,” a lot of the dissent quieted down. Besides these word games, of course, the police were promptly deployed to various locations, including local residents’ homes and the universities via the student counseling (fudaoyuan) system, employing surveillance and threats in order to prevent people from expressing their opinions or taking any kind of action. Not to mention the media. Under these circumstances, a few people [i.e. we] went to the villages and fisheries to see for themselves what was going on.

What [we] discovered was that this case was similar to many other conflicts over land. First, the developer had obtained the land near the lake via a nominal “land deal” and started developing it. The people who thereby lost the [collective but effectively state-owned] land [whose use-rights they had previously been entitled to], namely the local villagers and fishery workers, were made to accept compensation and move away. This “deal” was worked out in a top-down and secretive manner, and the allocation of rent, etc., was skimmed off by individuals and offices at every level of the power structure, so by the time it got down to the villagers and fishery workers, the amount of compensation they received was unreasonable. In order to make them accept it, then, violent forces comprised of people from the government (civil servants, police, urban management personnel, etc.), village “strongmen” (a popular term for villagers with connections to the government who are accustomed to employing violence), and security guards the developer had “hired” were used to evict the original inhabitants from the land.

With regards to the wording “forced demolition,” it should be pointed out that this violence did not take place merely during the time when houses were actually being demolished, but in fact started when the village elections were sabotaged (usually through collaboration between the government and the village strongmen). According to villagers, in the past they would vote for villager representatives (one for every ten households) according to the Village Committee Elections Law on “democratic self-government,” and the representatives would negotiate how to manage the village’s collective property together, now the “strongmen” force other villagers to vote for them using violent means right in front of the supervisor cadres sent down from the government. This is how, when it came time to distribute the land rent, the strongmen-led village committee monopolized the right to determine how distribution would work, and the villagers were forced to accept it.

Actually, “filling in the lake” is just another form of land-grabbing, and there is already enough intense criticism of that practice. Something that became apparent to those intervening from outside—whether they be investigators or activists, etc.—who took up an environmentalist perspective on this piece of land and wanted to protect it from violent redevelopment, “filling in the lake” (let’s set aside for now the bickering with managers of “state capital” over whether it’s actually the lake itself or a separate “pond”) revealed itself to be a real issue that could not be stopped in the face of a combination of state violence and the inability to criticize the conversion of the function that the land was being used for. In fact, with regards to the filling in of East Lake, a common understanding became established among all those connected to it, whether through property rights or use rights: The problem was seen not as redevelopment in and of itself, but merely the unfair distribution of benefits among people with prior land-use rights as those rights were being transferred [to the developers]. Regardless of the starting point for those intervening from outside, what those losing their land expected from them was to expose the violence and corruption, and in this way help them to achieve a more equitable redistribution of land rents.

Despite all the intense criticism of state monopolization, violence, corruption, strongman politics, “free market mechanisms,” censorship, etc., which all took place throughout this process, the criticism never amounted to a collective force, or even “public pressure” that would make the government act prudently. The government, capital and even violence had free reign, and the Happy Valley amusement park and the luxury condos, hotels and shopping areas around the lake are already being built. Now that all of this seems to have become a fait accompli, the “happy” landscape is cacophonous. What so many have cautioned and urged is that we need a new “language,” but how can we find a language among so many variations of “lake filling”? I think all these suggestions have one common feature. No matter whether they are focused on “conservation,” a “more equitable redistribution,” or other aspects, what does “lake filling” mean anyway? Beyond the change in land status, beyond the corruption and violence of power, it is still necessary to look through all of this to an implicit commonality that operates simultaneously between the land itself, the dispossessed, and the so-called “people intervening from outside” (“the people” as owners of public space). A new mechanism of production, for example.

In this sense, the people intervening from outside (maybe we should call them “activists”) get stuck within the limits of the “lake filling” perspective, unless we dig into the seemingly simple but actually complex issue of property rights that is being covered up by it. First of all, under the “national ownership” and “collective ownership” systems of land ownership mandated by the state,6 the only time the dispossessed are approaching the “ownership” of land is in the process of leaving it: The land is controlled by a privileged strata (who plunder it through taxes and have full decision-making power over its use), but when its status and function are being modified, the dispossessed gain a limited right to dispose of it personally. Only with the capitalization of land and its parceling out, the dispossessed’s theoretically collective ownership finally achieves a degree of reality. But through the transformation of their status as “citizens” (with the change from an agricultural hukou[household registration] to a non-agricultural one) and their welfare mechanisms (access to the Minimum Living Standard Guarantee, pensions, basic medical insurance, etc.), and with the villages turning into joint-stock companies, etc., the dispossessed are integrated into what the state calls the “transition” of its economic model of social development. Therefore, the “filling in of the lake” is connected to the national transformation of mechanisms for economic management. The transformation of functions linked to the change of ownership—namely, [fostering] “creativity,” the channeling of people’s attention toward their physical bodies, and “greening” [superficial beautification through landscaping]—is, of course, aimed at satisfying the elite’s desires for a better environment, etc., but broader sections of society have also begun to identify with this [ideology]. So one of the more interesting questions that emerged from our investigation was: What kind of “alternative” or “substitutive” critique was possible, in contrast with this kind of identification?

Zijie: We conducted an on-sight inspection of the northwest corner of East Lake where it was being filled in, and we interviewed experts from the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Hydrobiology [located on the shore of East Lake]; local villagers, fishers and others who lived near the lake; students and urban residents of Wuhan; lawyers; the East Lake Scenic Area Management Committee (in that order), etc. The answers to the question of whether the lake should or shouldn’t be filled in were naturally negative, but parallel to that there were lots of disagreements concerning people’s visions of economic development for the area surrounding the lake. The villagers themselves are a complex group, and what we found the most discouraging was our inability to communicate with those villagers most affected by the filling of the lake. [Common responses that we got were] “I don’t understand what you’ve written,” or that they felt “completely helpless” about the whole thing. Most villagers chose to play it safe in a bid to increase the amount of economic compensation they might get, while their common aspirations were held hostage by the strongmen. [They felt that] the land was not really theirs. Internally, “the weak” within village politics held themselves back in comparison to “the strong,” who allied themselves with external capital and the government in applying pressure and the promise of small benefits [if they complied]. This made it hard for activists, as another external entity, to make common cause with the disempowered villagers. As Mai Dian put it, we failed to find a point of entry fast enough concerning the complex issues involved: environmental conservation, the interests of the majority vs. the minority, the supremacy of capital, strongman politics. In other words, we ultimately found ourselves powerless when it came to concrete actions of resistance on-site.

Mr. Po: Can you tell us something about the Thirty-Meter Memorial Wall artwork that you did with Wu Yun and Zijie? How did Wuhan Municipality’s “Regulations on the Management of the East Lake Scenic Area” and the “Guidelines for the Management of Lakes” come to feature in it?

Mai Dian: The Thirty-Meter Memorial Wall attempted to illustrate the figurative and, to a certain extent, actual “flexibility” of the changing physical borders of what’s termed “public space.” “Public space” was originally a way to get involved in this issue through means best described as juridical, because, according to the ordinances, East Lake was defined as a “public space.” As we all know, however, this is a paradoxical concept in China. In a sense, the whole “realm” (率土之滨) belongs to the entire population, collectively—it is common. On the other hand, these “commons” are governed by so-called “representatives of the advanced forces of production.” In the case of East Lake, this is a de facto public space, precisely as the keyword “free access” (免费接近) is defined in the East Lake Art Project’s initial call for action: It’s a location where the public can enter and move around without having to pay. But these “commons” can easily be taken away, just as easily as the administrative regulations can provide it. So we can see how meaningless it is to talk about laws in China. But here “law” can be made into a point of reference, since it allows us to see more clearly the persistent negation (within the national sphere) of laws managed by the executive powers of the state. So in a time of so-called “public crisis”—and the Chinese government’s public relations department, which has already absorbed this concept, handles any “public opinion” as a crisis—the best way to deal with crisis is by making a performance out of “law.” […]

In order to “protect the lake as one would protect the one’s own eyes,” a new “iron law” was officially floated: a provision called “Wuhan Municipal Lake Regulations and Management Guidelines” prohibited development within a 30-meter green belt. According to experts from the Institute of Hydrobiology, a buffer zone should be at least 100 to 200 meters wide. These mere 30 meters were granted only after residents had begun protesting against the development project. Although nominally this was meant to limit development, in truth it was to apply false eyelashes after plucking out the real ones, since nothing was left apart from the naked eyes. “Public space” was now limited to 30 meters around the lake, and this was the baseline (even though there was also the 300 meter controlled area) of what was “collective.” The media fanfare about the mayor’s “iron determination, iron discipline and iron handling” in addressing the situation was really just a way of making administrative officials appear to adhere strictly to the legal yardstick at first, before later backing off and letting developers take most of the land.

It’s not that we want to argue over whether this number is scientific, but that when it came to fixing the number, the “entire population” was finally barred from participating in decisions about the use of land that was supposed to be their own, in an institutional sense. Power can change “public space” on a whim, and practical consequences of this are settled via disputes over numbers. When you add this to the developer’s reputation for “green landscapes,” the redevelopment of this land came to seem a matter of course. Perhaps for a lot of people, it seemed as if “the environment was being improved,” as we heard some of them say in interviews. But what this behavior erased, along with other behaviors that have been criticized, was precisely the various problems implicated behind the scenes in the process of constructing this spectacle (景观). According to the definition of “public space” in terms of speech, these problems should be discussed publicly. Of course this wasn’t possible, nor did it even become possible. Put simply, this was why at the time we thought of using the remains of this wall beside the lake as a kind of memorial.

Zijie: The East Lake Fishery, formerly within the East Lake Scenic Area, is a former state unit that was mainly responsible for replenishing fish stocks and fishing production in the lake area until the late 1980s, when the fish stocks were able to suppress the bloom of algae in the lake. After OCT bought the site and a large area of land to the north, it was rumored that a five-star hotel would be built on the site of the original production unit. This was later “debunked” with the claim that a public green space was to be built there rather than the hotel itself, and the “Wuhan Municipal Guidelines for Managing the Restoration of Lakes” stated that no development would be allowed within 30 meters of the shoreline along the lake. But the reality is that the lake’s natural shoreline is far from clear. There’s an extremely long and uneven buffer zone between the lake and the places where people live, consisting in some places of wetlands, farmland and ponds, which are a habitat for wildlife and vegetation. Mai Dian already talked about public space, so let me add something about ecology. We found this broken wall in the fishery, which was probably a remnant of the fishery workers’ dormitory, just over thirty meters long, and perpendicular to the shoreline, dividing the fishery into two parts, north and south. You can use this wall to see how the so-called 30 meters cannot be made into a point from where the development of public areas begins. Now, the OCT’s hotel has appeared on the planning map again, and the line divided by this wall may become a park in the south, and a five-star hotel in the north.

The project’s insistence on its opposition is particularly evident when we view it in the context of a tension between the confiscation of land and the eviction of its inhabitants, on the one hand, and the participants’ active withdrawal in order to intervene in the eviction and maintain that intervention, on the other.

Mr. Po: As initiators and participants, what do you think of the “East Lake for Everyone” art project? From its the first round in 2010 to the second round this year, how have your views, understanding and thinking about the project and the whole matter of the lake changed?

Mai Dian: I need to point out that the “East Lake for Everyone” project was actually started by the two artists Li Juchuan and Li Yu, and I was not an initiator but only a participant. I only became an “initiator” the second time around when I joined other participants with an increased degree of concern about the matter.

With regards to joining the action, under conditions where public opinion is being stymied on all sides, the art project found an important propaganda channel. This was the obvious goal that Li Juchuan and Li Yu had. I’m an outsider to art; it’s something I know very little about. What attracted me more to the project was the way it brought participants together. At the time, among those making the inquiry, a kind of “affinity group” (亲密团体) approach to action was beginning to be stressed. That is to say, among those making the investigation there was no need for any status mechanism, the emphasis instead being placed on informal alliances among individuals with similar minority perspectives, etc. As it happened, the idea of an “art project” seemed to accord with this. It was different from other art projects in the sense that it was less of an organization and more of a platform with different viewpoints converging on this basis and each individual preserving their own independence—in both their creations and their perspectives—while releasing their artworks on this platform. The project had no curator, just initiators. Generally speaking, initiators are rarely able to avoid the mechanical tendency to become “opinion leaders,” but the initiators of this project Li Juchuan and Li Yu not only rejected the “leadership” of curatorship, they even more strongly rejected “directorship”—which is a more pernicious form of power and influence regularly employed by intellectuals and professional artists. Consequentially, aside from the fact that initiators of the project get more opportunities to talk and thus talk more—for example, you are at this moment inviting me to comment on the project—this art form is still fairly anarchistic, and participants have ample ground to express their opinions in their own ways.

This anarchistic platform appears to be formalistic and unable to take effective action in the face of events—for example, by stopping the lake’s redevelopment. But if we take a closer look at the reactions it provoked, we can see a more crucial point, such as the transformation of the productive mechanism we came across in the second question. The reason why the government doesn’t pay a lot of attention to art projects is, firstly, because they don’t attract great numbers of people and, secondly, because art is seen as a part of the “creative economy.” When the function of this piece of land changed, it nominally shifted towards the creative economy. In fact, the art project did receive attention from the art world and the “theoretical” milieu. Li Juchuan was even contacted by the company OCT: its Wuhan branch got in touch with him via personal friends and even extended, in a somewhat threatening way, a tentative invitation for the Art Project to collaborate with them in the future. The offer was obviously insincere, but it could become real if one cooperated. Within art circles, the project was of course seen as a form of rejuvenation. Just look who is closest to the shoreline: Of the new features next to the 30-meter greenbelt, the OCT Contemporary Art Terminal (OCAT) and the “creative district” (创意街区) are the closest, even closer than the lakeview houses. One of the key points the state-led “economic transition” is focused on—and which is quite fashionable in China—is that artistic dissidents can also be turned into “forces of production,” and that the accumulation of capital increasingly depends upon the “autonomy” of producers.

At a time when dissident art has in many places become the vanguard of gentrification, the more distinctive feature of “East Lake for Everyone’s” oppositional stance has been its refusal of, or at least a more cautious attitude toward, invitations sent out by institutions such as OCAT. It appears, in retrospect, as a form of dissenting opinion, that refuses to be institutionalized and enter the system of circulation. And although it is unable to completely isolate itself from this system, it maintains a role of an active “exit” (离开). The project’s insistence on its opposition is particularly evident when we view it in the context of a tension between the confiscation of land and the eviction of its inhabitants, on the one hand, and the participants’ active withdrawal in order to intervene in the eviction and maintain that intervention, on the other. This tension is inadvertently lost in a tendency toward “commonization” (共同化)—the peasants, the fishery workers, and the participants in the art project are all more or less involved in a process of institutionalization: Each individual is oriented toward a dispersed, autonomous condition; toward becoming a so-called “individual-capitalist” (个体-资本者). In the redevelopment of East Lake, together with the new policies and trends of joint-stock villages and “villagers’ autonomy,” such features are becoming more and more obvious. “East Lake for Everyone” can be understood, at least out of context, as a kind of critical distance similar to that achieved by reverse architecture: “By prolonging the process in time… architects postpone its inescapable fate, creating a gap through which we gain a brief critical distance from the reigning view of architecture and the building activity that blinds us to the erasure of the environment.” (On “Reverse Architecture,” quoted in “9119 Cyril Street,” Architecture Bulletin, edited by Li Juchuan and Hu Heng, October 2001.)

Zijie: During the first round of the East Lake Art Project, I think it was because people encountered multiple obstacles to expressing their views that they decided to look for a different outlet [the second time around]. Even after the second time, I still think the project is verging on a sense of powerlessness. (Is this local after all?) But this doesn’t necessarily mean that it hasn’t had any impact—in carrying out refusal and continuity.

Sample Artwork from the “East Lake for Everyone” Events

East Lake for Everyone (Round 1), 2010

59 artworks by 53 individuals & groups

Thirty-Meter Memorial Wall 三十米纪念墙

As discussed in the interview above, local student Wu Yun 乌云, illustrator Zijie 子杰, and musician/ odd-jobber Mai Dian 麦巅7 discovered the remains of a wall from an old state-owned fishery workers’ dormitory, mysteriously left behind when the rest of the complex was demolished. They measured its distance from the lake and found it to be 33.7 meters, possibly revealing the origin of the official rule that a greenbelt of 30 meters must be preserved to protect the lake, in contrast with the 100-meter buffer zone recommended by ecologists—in any case disregarded when it came to granting OCT permission to build right on the lake’s surface. The artists took advantage of this coincidence to decorate the wall with signs reading “No development permitted within 30 meters of the shoreline – from the Wuhan Government’s Regulations on the Management of Lakes.” They also conducted an archaeological analysis of the “remains of life” from the dormitory found in the wall and surrounding rubble, and they charted the 30-meter line on Google Maps.

For Free 免费的XX8

Theater worker Wu Meng 吴梦 organized this piece of interactive “social theater,” on a portion of East Lake that was still open to the public and frequented by locals, together with members of Desiree and two left-leaning theater collectives: Shanghai-based Grass Stage (草台班) and Wuhan-based Rivers & Lakes (江湖戏班). These included Mai Dian (featured in the video below on guitar), Zijie (who helped with filming), Grass Stage founder Zhao Chuan, and Grass Stage member / Marxist scholar Christopher Connery,9 among many others. Below is a video of excerpts from the performance with English subtitles.

Bluestar Photographic Records of East Lake 东湖影像记录活动

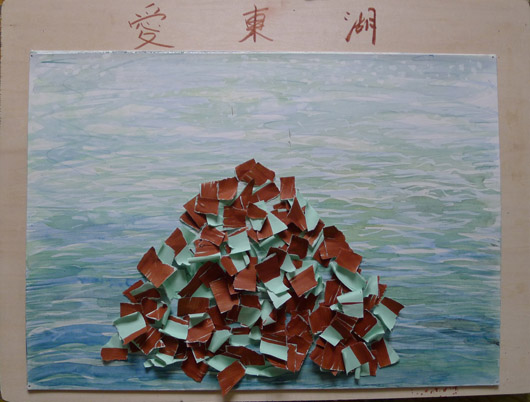

Local college student Xiaotie 小铁 (then member of Désirée, now head of the Beijing LGBT Center) organized a group to take photos and videos of people strolling by the lake, recording their statements about the lake and thoughts about the development project. These were then broadcast on Weibo (China’s equivalent to Twitter) and compiled into a map of the lake. (The map’s caption below reads “Can’t Wuhan’s 8,312,600 residents defend the integrity of East Lake”? The red patch indicates the portion of the lake’s surface scheduled to be filled in for development.) The name “Bluestar” and its logo were created for this purpose, with the idea that everyone could become a star by defending the lake against redevelopment so its water could remain blue.

Hot Dry Schizophrenia 精神病人对时代的反诊断

Swiss artist and Désirée resident Yovski organized an event at the space, sharing his paintings themed around “a so-called mental patient’s counter-diagnosis of a so-called pragmatic era.” While the paintings were mainly autobiographical, the discussion about them linked their “counter-diagnosis” to the critique of capitalist rationality behind the destruction of East Lake.

Fuck Your Happy Valley (Round 2), 2012

40 artworks by 33 individuals & groups

Fuck Your Happy Valley, Where Are My 200 Mu? 去你的欢乐谷 找我的两百亩

Local musician Wu Wei 吴维 (singer of the punk band SMZB)10 hung a megaphone on a parking sign equipped with a surveillance box at the former entrance to the fishery where 200 mu, or 12 hectares, of the lake’s surface had been filled in to build the Happy Valley amusement park—now blocked by a billboard advertising the park. For ten hours, the megaphone played a recording of his voice shouting, “I’m looking for 200 mu! 200 mu, where are you?” The sign Wu holds in the photo below reads “Fuck your Happy Valley, gimme my 200 mu!”

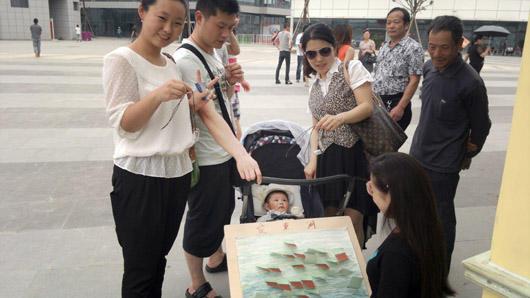

Unconveyable Wishes 送不出的祝福

Local student Zeng Li 曾莉 prepared an “East Lake Appreciation” board with strips of paper (colored blue and brown to represent the water and the land) for people to write out their wishes, and sixty tiny bottles to contain them. She then went to the entrance of Happy Valley to distribute them to people lined up buy tickets, explaining the background about OCT and the development’s environmental impact. At first she had managed to convince the security guards to let her do this on the grounds that she wasn’t disturbing the peace, but after she had given out ten bottles, a man who wouldn’t identify himself came, called her into an office for questioning, and finally had the guards kick her out without an explanation. She took the remaining strips of paper and crumpled them into the shape of a tomb to mourn the death of “the bond between the land and the water.”

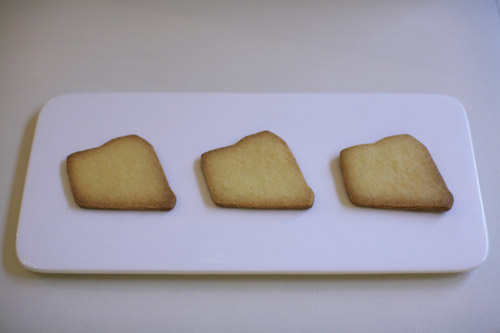

Happy Valley Cookies欢乐谷饼干

Local Wuhan artist Zhan Rui 詹蕤 and office worker Yao Lei 姚蕾 made fifty cookies in the shape of the 200 mu (12 hectares) of the lake that OCT had filled in to build a Happy Valley amusement park and then distributed them to people standing in line. (This occurred a few days before Zeng Li’s wishing bottles, which may explain why he was not kicked out but she was.)

Shoreline 2009.1.22 湖岸线

Zijie and Li Lu 李珞 (a filmmaker originally from Wuhan) spray-painted blue markers indicating where the shoreline used to be, approximately every hundred meters along the perimeter of the filled in area.

Everyone Come and Make Public Art (Round 3), 2014

39 works by 34 individuals & groups

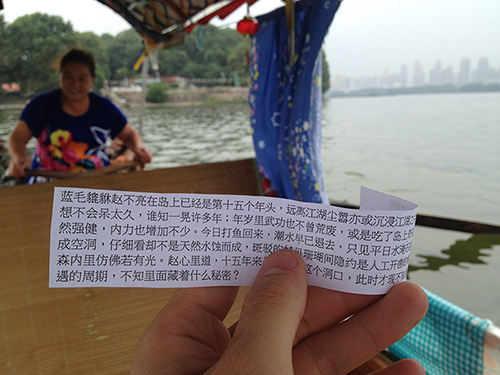

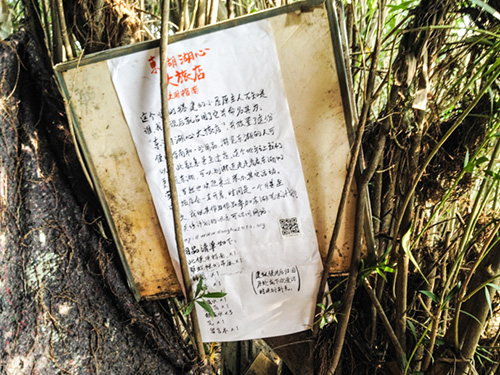

A Misty Record of East Lake 东湖飘渺录

Zijie and friends organized a live-action role play game involving a scavenger hunt around East Lake, inviting players to “piece together, connect with one another, and fill in” the lake “with their imaginations manifested through space.” The first item on the list was a copy of Sober Living for the Revolution: Hardcore Punk, Straight Edge, and Radical Politics, with the next clue inside: a poem transcribed from the wall of a temple.

One stop along with way was the “Lake Heart Hotel”—a hammock with a stool, a mosquito net and other essentials, along with a letter explaining that anyone could stay in the hotel for free to observe how the lake and its surroundings were changing, and to organize activities.

East Lake Station 东湖站

Artist Ge Yulu 葛宇路 (infamous for staring back at surveillance cameras and installing a street sign bearing his name) moved the sign for a bus stop in Beijing called “East Lake” to the middle of the lake in Wuhan. (He explained that the sign had seemed to be in the wrong place, as there was no body of water called East Lake in Beijing.)

Tribute 贡品

Artist Yao Wei 姚薇 (originally from Wuhan) filmed her family making a raft out of old tires, and then her father floating on the lake with a chicken while playing “My Ancestral Land” on the erhu (two-stringed fiddle), with continuing lakeside construction in the background. Still from the video below:

我们家 : Desiree Social Center : A Liberated Space in Wuhan

From Black Rim #1, 2010

Last December I had the chance to travel to Wuhan with some other members of the Beijing Anarchist Study Group. Wuhan, which is known as the birthplace of Chinese punk, spawned a small network of anarcho-leaning youths with a strong desire for autonomy and free expression. This is the same scene that produced the magazine Chaos, which is probably the first anarchist publication to come out of mainland China in fifty years. Chaos carried articles on the situationists, green anarchy, and ran translations of Kropotkin, all alongside reports from domestic and international punk scenes. Though now defunct, it’s final issue was a complete translation of Crimethinc’s Fighting for our Lives. It ambitiously tackled political issues, which is all the more impressive considering the repressive national context. The fact that the magazine wasn’t suppressed (though it was printed illegally) is a sign of a thawing of anarchism in China, which has laid dormant since the Communist takeover.

MD, who edited Chaos, is now in the process of cultivating a social center in the countryside just outside of Wuhan. Together with some friends he found a large house with cheap rent right next to a hog farm. In Chinese they call it 我们家, which means “our house”, or Desiree Social Center, in English. MD had extended an invitation to us in Beijing so that we could come see what was happening and how we could help. We gave some talks on topics like Chinese leftism, D.I.Y., anarchist theory, and the Zapatistas. These were all decent but what was really needed was a frank discussion on logistics and desire. We eventually got around to why the social center was formed.

MD explained that the Desiree Social Center was created in response to the general oppression of youth in Chinese society. Young Chinese people are forced into a schooling system that burdens them with intense competition. The Chinese school system instructs students that in order to get a good job and have a fulfilling life, the only option is to forfeit one’s childhood to test preparations and grueling study regimens. Yet, the portion of students who make it into one of the country’s colleges is incredibly small. Not only the educational system, but also the traditional notions of patriarchy and filial piety constrict young people in China. In fact, MD sees these forms of familial oppression as the root problems in Chinese society.

The people in Wuhan got into punk rock because it was a way for them to move beyond the confines of family and society. In the beginning, the Wuhan scene had all the best elements of the punk ethos: freedom, equality, transgressive communication, and ruthless anti-commercialism. As it got older, the scene got staler, until it is now a parody of its former rebelliousness. Now all the bands just want to make it big. The social center, on the other hand, is an attempt to reconnect to the roots of their rebelliousness, to organize resistance, and to create a space with meaning.

The center still struggles with its daily operations, as WF, one of the people who lives there, pointed out. Nobody involved in the center has ever tried something like this before. They get no money from operating the space; they don’t sell anything. The center is out in the countryside and the distance from the city gives some people reservations about going out there for events at night. This isn’t to mention the freezing cold of a winter without heat and the scorching heat of Wuhan’s summers. In some appreciable ways, they’re making it happen in the face of a lot of adversity.

Further Reading

“The Alternative Education of a Chinese Punk” (our translation of a 2009 autobiographical essay by Mai Dian, with more background to the founding of Desiree)

“This society is creating angry youth: memoir of a punk in Wuhan” (our translation of a 2014 autobiographical essay by Pengpeng from The Drifters, for context on Wuhan punk scene)

“An Interview with Wu Wei” (by Shayan Momin, 2014)

(Un)Locked: Memories of Wuhan (2021 issue of Scale, edited by Clément Renaud and Dino Ge Zhang)

反抗地产资本的“跳东湖”,为何成为了地方消费文化符号?[How did ‘Jumping into East Lake’ in protest against real estate capital become a symbol of local consumer culture?] (2021 article from independent left platform Companion / Hxotnongd 同时)

抵抗的未来:写给“每个人的东湖” [The Future of Resistance: On “East Lake for Everyone”] (a Situationist-influenced review by Fen Lei from 2013)

諸眾: 東亞藝術佔領行動 [Multitude: Art and Occupation Actions in East Asia] (2015 book by高俊宏 with a chapter on Desiree, from 遠足文化)

Notes from Chinese Original

[i] 姚海鹰《武汉华侨城东湖开发调查》,载《时代周报》2010年3月29日(3月24日提前出版)B01财富版。可见姚海鹰博客:http://yaohaiying315.blog.sohu.com/146900373.html(2015年7月7日访问)。

[ii] 华侨城集团声明,见 http://news.dichan.sina.com.cn/2010/04/02/142047.html;其他相关发言,见http://news.dichan.sina.com.cn/wh/2010/04/02/142013.html(2015年7月7日访问)。

[iii] 2010年5月华侨城集团在媒体上公布的规划平面图及项目情况介绍,见

http://www.cnhubei.com/ctdsb/ctdsbsgk/ctdsb01/201005/t1138794.shtml(2015年7月7日访问)。

[iv] 李巨川《“每个人的东湖”艺术计划访谈》,《美术文献》2010年第5期(总67期),见:http://donghu2010.org/?p=117 ,或 http://www.douban.com/group/topic/17408285/ 。以及《麦巅和子杰答泼先生问》,载泼先生编《东湖行动》(2014),见:http://www.douban.com/group/topic/38924531/ 或 http://donghu2010.org/?p=154 。

[v] This referred to what was displayed on the company’s website as in April 2012. Since then it has changed the wording to simply “platinum five-star hotel,” and the large 3D has been replaced by a less dramatic image: http://www.octwuhan.com/.

[vi]《李巨川答泼先生问》,载泼先生编《东湖行动》(2014),见:http://www.douban.com/group/topic/38783280/ ,或 http://donghu2010.org/?p=156 。

Editorial Notes

- In that article (Gleaning the Welfare Fields: Rural Struggles in China since 1959), we noted that “Urban participants in this movement (including at least one self-described anarchist of rural background) said that they approached some of the 50 rural households still resisting only to discover that their goals were incompatible: whereas the urbanites wanted to prevent the development project and keep the lake as it was, the ruralites wanted an increase in compensation. They were not even willing to consider the option of keeping their land and houses. Most had jobs in the city and, even if some used part of their land to supplement their incomes by farming for household use, they valued this less than the money they hoped to obtain in return for giving up their land.” The analysis concluded that this case demonstrated “the difficulty of linking such localistic and narrowly-defined struggles with broader movements that might take on a potentially anti-capitalist orientation.” The materials presented in this blog post seem to confirm this analysis, overall, but they also point to a more complex and nuanced picture of the movement. Setting aside the questions of rural conditions and political potentials explored in that article, our main goal in presenting these materials now is instead to provide a more detailed window into events that have influenced ongoing developments within China’s internationalist left.

- This autonomous space (a house in a rural village next to East Lake) was originally named “Our Home” Autonomous Youth Center (“我们家”青年自治中心) in 2008, then re-named Désirée Autonomous Youth Lab (“我们家”青年自治实验室) in 2009. The Chinese name changed only the “Center” to “Lab,” to reflect that its members aimed for the space to function not as a center of anything (in a hierarchical sense), but instead as a place for experimentation with new social relations, or forms of life. The main part of the Chinese name continued to be Womenjia, meaning “Our Home,” but Désirée was adopted in English to honor a friend by that name.

- This post is also timely given that mainland media collectives influenced by the East Lake movement have recently published a number of articles and translations related to anarchism, “disaster communism” and environmental struggles in other countries, such as this one about the movement to defend the Atlanta Forest against Cop City.

- This article was based on interviews with participants along with the following sources (mostly down now):

http://www.douban.com/people/desireeyac/notes

- Originally from a pamphlet titled East Lake Action 东湖行动 compiled by “Mr. Po’s mutual aid project”

- On China’s changing systems of collective and state land ownership and household use-rights, see “Gleaning the Welfare Fields” (from Chuang #1, 2016) and Feng Deng, “Land development right and collective ownership in China” in Post-Communist Economies, 25:2 (2013).

- For background, see Mai Dian’s 2009 autobiographical essay “Alternative Education of a Chinese Punk,” and listen to tracks from the 2006-2014 hardcore band Criminal Minds (犯罪想法), where he played guitar.

- “For Free” is the English title given to this piece by the artist. The Chinese title means “free unknown,” using “X” in the mathematical sense of a variable, indicated colloquially in Chinese as “XX.”

- In “World Factory,” Connery’s article on Grass Stage’s play by that title, he writes: “The Huaqiao company” (i.e. OCT, in whose Shenzhen theater the play was performed in 2014) “had been behind a development on East Lake in Wuhan to which a broad spectrum of Wuhan activists—students, faculty, artists, plus key members of the Wuhan anarcho-punk community—had organised a popular opposition movement. I was close to many of them and had participated in some of their activities. I told Zhao Chuan I could not in good conscience participate in an activity that Huaqiao sponsored. It was a painful exchange, but I agreed to go to Shenzhen anyway and to speak at a forum, provided I could mention why I was not on stage (it is still a matter of debate whether or not it was my criticism of the Huaqiao company that resulted in the artistic director’s dismissal shortly thereafter).”

- In a 2014 interview, Wu Wei said of the initial 2010 mobilization to defend East Lake, “At one point, we were planning a demonstration for about two weeks. I think it was going to be on a Saturday. When I showed up at the bar to work the day before our demonstration, the phone rang. It was the cops. They said they wanted to meet up with me to chat about something. I didn’t want to draw any attention to this bar so I told them I’d meet up with them somewhere else: a coffee shop in Guanggu. I ran over there and there were two cops waiting at the entrance of the café. They took me to their car. One cop sat in front and the other sat in the back with me. The cop in the back started interrogating me about our plans—when we were planning to go, who was involved, all kinds of shit. I’d answer vaguely or feign ignorance, but the cop in front knew the answers to all the questions —he had copies of my emails and transcripts of my private chat sessions with people who were planning protests and demonstrations. They wanted to verify the information they already had. They even had my text messages!” Also see this review of SMZB’s 2020 album Once Upon a Time in the East, with several music videos.