Around the world, previously invisible delivery personnel have achieved a new prominence in popular consciousness as “frontline workers” throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. As the emergency has highlighted both the importance and the dangers of delivery work, strikes over working conditions have occurred alongside public displays of appreciation. In China, the sector had already become a focal point of unrest several years ago, as both capital and labor flowed from the declining factory sector into services in general and the minimally regulated new e-commerce platforms in particular. While lockdowns in the early part of this year limited in-person organizing, the past few months have seen a revival of labor actions combined with a flurry of media exposés about the industry. Express parcel couriers seized upon the lead-up to the November 11th shopping holiday, “Single’s Day,” with protests, slowdowns and mass resignations reported in multiple cities over the past weeks. And two months ago, one of China’s most widely read magazines, Renwu (人物, “People”), published a long-form inquiry into the horrors of food delivery work, based on six months of research. The report has been widely reposted and viewed 3.16 million times via the original link on Weibo alone, sparking a series of related articles. Below is our translation, prefaced by a summary and brief commentary. In the coming weeks we will publish an original text analyzing what these nightmarish trends in “platform capitalism” reveal about China’s economy as whole within its global context.1

The report, titled “Delivery Riders, Trapped in the System” (外卖骑手,困在系统里) and collectively authored by a team of unnamed journalists at Renwu, was published on September 8th, 2020. The monthly magazine Renwu was founded in 1980 under the People’s Daily Press and is now run by the state-owned People’s Publishing House, which mainly publishes political books. In March, Renwu ran an interview with Ai Fen, one of the first doctors to share information about the COVID-19 outbreak despite warnings from her hospital to remain silent. The interview was deleted within hours but was shared widely through a variety of creative methods to circumvent censorship, including the use of emojis and the reversal of word order. The piece translated below provides another examination of individuals whose expression and lives are being held hostage by forces beyond their control. The article intersperses worker interviews with data about the industry, examining not only the impact of algorithmic controls upon the workers themselves (known as “riders” because they deliver food and other items by riding electric scooters), but also the ways in which outside actors contribute to this system, as it controls them in turn.

Summary

Since this is particularly long piece, it will be helpful to first give readers a summary of the contents. The opening section, “Order Received,” recounts the increasing pressure placed on riders by shrinking delivery time limits. As iterative machine learning processes push for ever shorter delivery times, an accomplishment celebrated as a triumph of technology by the algorithm’s creators, the riders have no choice but to violate systems of traffic control in an “inverse algorithm.” Later sections “Navigation,” “Smiling Action,” and “Five Star Ratings” delve deeper into the threats to public safety created by this process and the further displacement of responsibility away from companies and onto riders.

“Heavy Rain” begins to question this “triumph of technology,” revealing that a single weather event is enough to topple the algorithms’ utopia of efficiency. Like many allegedly “smart systems,” the platforms’ algorithms require human intervention (and even operation) to function. It is here that the curtain is pulled aside, with an Ele.me supervisor admitting that this intervention is done to make conditions more difficult for workers. Ultimately, those with power to change the system have chosen to do nothing – or even to exercise that power to further push riders to the limits of their ability in pursuit of even greater profit.

“Navigation” investigates how the use of an algorithmic system allows the platform to generate demands that would be unreasonable from another human, including driving against the flow of traffic, achieving delivery times that would only be possible by flying, and even going through walls. “Games” further investigates the impacts of algorithmic control, arguing that the gamification of rider wages gives the appearance of greater independence for workers while in fact subjecting them to a system of control that shapes their very perception of reality.

The sections, “Elevators,” “Gatekeepers,” and “Coca-Cola and Peppa Pig” delve into riders’ relationships with building management, restaurant owners, and customers, respectively. Each relationship represents a variable in the delivery process which the riders, facing the “constant” of delivery time assigned by the algorithms, must bear the burden of mitigating. Often these variables require the exercise of emotional labor, and the workers’ subjection of themselves to a system dominated by the whims of the consumer and the production of products over which they have no control. Notably, “Coca-Cola and Peppa Pig” demonstrates how the algorithms shape reality not only for riders, but for consumers as well – one customer notes that while previously he had been quite happy to watch TV while waiting for his food, he now finds it unbearable due to the unrealistic delivery time provided by the platform.

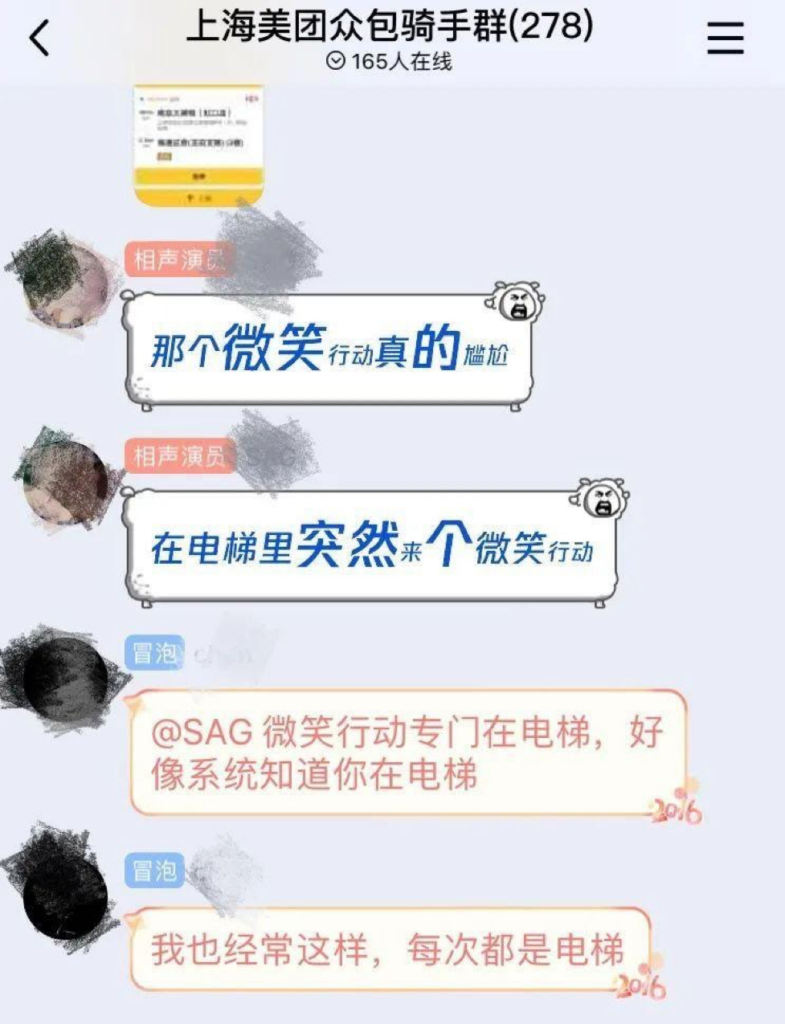

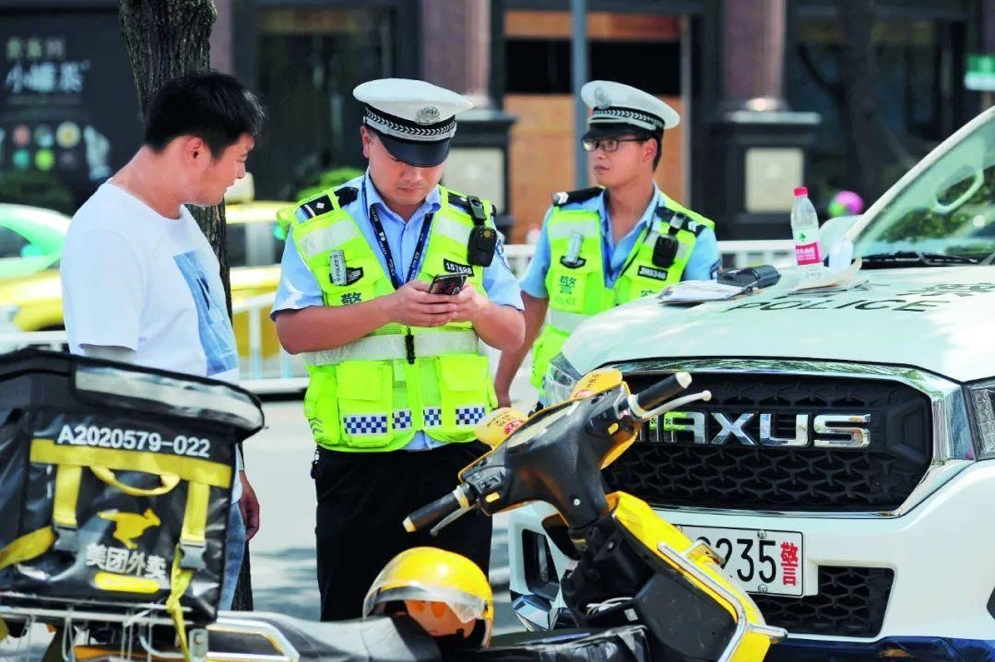

The sections “Scooters,” “Smiling Action,” “Five Star Ratings,” and “The Final Safety Net” investigate the systems that further push risks onto riders while ensuring that profits continue to accrue to the platforms. In “Smiling Action,” Renwu illuminates how the platforms’ attempts to defray public criticism regarding accidents involving delivery riders with random safety checks (given the Orwellian name “Smiling Action” by Meituan) further subject riders to heartless and inconsistent systems of control. Interviews with police officers in the section “Five Star Rating” demonstrate that government responses have further shifted blame and responsibility for threats to safety onto riders. Rather than constructing transportation infrastructure better suited to growing numbers of delivery riders, or enacting laws that address the algorithmic factors pushing riders to violate traffic laws, cities have instead opted to surveil and punish individual riders. Although the officers interviewed express sympathy for the riders’ plight, they continue to enforce these laws against riders. While punishing riders for infractions, these officers often take up the task of delivering food, ensuring that even though individual riders are punished by the legal system, the system itself remains unchallenged. The officers have ultimately become conscripts of the algorithm. “The Final Safety Net,” which covers the inadequacies and denials of insurance coverage by platforms further illustrates the vulnerability of riders in the absence of formal employment contracts.

The closing section, “Infinite Game,” briefly turns its attention to the programmers themselves, suggesting that they in turn are trapped in service of a larger system, with an educational background that has left them ill-equipped to adequately access the impact of the systems they designed on society. This section also alludes to broader concerns about personal data privacy that are gaining traction in mainland China, noting that even as riders’ data is used to refine the algorithmic systems of control, the ownership of that data remains under dispute. Ultimately, the article concludes, these actors are trapped in a “game” that they do not completely understand, with little choice but to keep playing.

Continuing the Struggle: Protests Escalate, But Can They Change the System?

Protests by waimai delivery riders2 had already begun to escalate prior to increased media coverage regarding the plight of gig workers. Strikes by food delivery riders have increased more than four-fold between 2017 and 2019, going from ten reported strikes in 2017 to at least 45 in 2019 according to China Labor Bulletin. Abuse of gig workers and delivery riders is a global and cross-sector issue. Riders in Brazil, South Korea, Thailand, and Romania have also joined protests calling for better working conditions in this year alone, according to data from ACLED. More recently, strikes and protests by kuaidi couriers, many of whom deliver orders from China’s flourishing e-commerce industry, have also increased, with Service Worker Notes reporting thousands of posts online regarding courier strikes just this year. Similarly to food delivery platforms, courier platforms have sought to expand their market share by cutting delivery prices, passing on those cuts on to their workers while the platforms’ revenue continues to grow. Workers from several major courier companies are protesting over wage arrears, with China Labor Bulletin noting that some expect these strikes to escalate around November 11, a popular online shopping holiday in China. According to Jinjiao Caijing (金角财经, “Golden Horn Finance”), Baidu search volume for keywords related to strikes by courier workers was up 2,235 percent year-on-year in late October, with deliveries already piling up in multiple cities.

Following the release of Renwu’s article, Ele.me introduced a function that allowed customers to indicate that they are willing to wait an extra five or ten minutes for their delivery, a move that was widely criticized as simply passing responsibility onto customers, according to Ziben Yixian. The day after Renwu’s article was released, Meituan announced that it would be allowing riders eight minutes of flexible time, and would extend delivery time and even stop orders during bad weather, mitigating the problems highlighted in the section “Heavy Rain.” However, riders highlighted that other problems with Meituan’s algorithm, including unrealistic delivery directions, remained unaddressed and highlighted that the “system is responsible” for the risks entailed in working as a rider.

While Renwu’s article offers little vision of a path forward and ends with the image of delivery riders pushing onward in an infinite game that they have little ability to control or even completely understand, other articles have focused on riders’ exercise of agency within or against the system. “Feeding the Chinese City,” a collection of interviews with delivery riders originally published by “Awaken Club” on WeChat and translated by Progressive International3 provides an alternative vision of delivery riders’ future. The article highlights mutual aid groups and the beginnings of responsiveness to the plight of workers from the national bureaucracy. Ultimately, the difference in these futures comes down to different visions of workers’ power within an algorithmic system of control. “Feeding the Chinese City” depicts fellow riders rushing to the aid of a fallen comrade, a behavior that another interviewee urges Chinese society as a whole to emulate. In “Delivery Riders, Trapped in the System,” however, a rider watches a fellow colleague get hit by a car and rides away, the ding! of a new order ringing in his ears. Thus far, Renwu’s cynical assessment of the factors at play seem to be more accurate: according to China Labor Bulletin, although the official All-China Federation of Trade Unions has identified delivery work as one of its “eight major sectors,” the system itself remains unchallenged, with benefits from union interventions “[failing] to address the fundamental problems endemic in the industry.”

We have chosen to translate this article not only for its useful investigation of the structure of algorithmic labor governance, but also for the interesting position that its publication––and the outpouring of similar reporting on precarious delivery workers––marks in regard to the economic position of delivery workers and the platforms that employ them. While we will explore the history and current dynamics of China’s so-called “platform capitalism” in our upcoming piece, with an eye to the role that the current media recognition of platform workers might play in signaling an end of the anything-goes expansion of platform industries, here we want to note the conflictual terrain that gave rise to these forms of reporting: Renwu’s investigation comes as China’s sluggish recovery following the COVID-19 outbreak has seen broadening inequality. Government stimulus has focused primarily on enterprises and middle-class consumers, rather than on the migrant workers who saw the most significant loss of income (as much as 75 percent during the height of pandemic lockdowns in February and March, according to Stanford University’s Rural Education Action Program). At the same time, officials such as Premier Li Keqiang have highlighted the informal sector as the solution to China’s rising unemployment. Finally, Renwu‘s investigation of the negative impacts of the Meituan/Ele.me duopoly comes as the Chinese government is seeking to assert increased control over major tech companies, with new antitrust guidelines released November 10th targeting tech giants including Meituan. On the same day, a post by the Cyberspace Administration urged Chinese tech companies not to allow Chinese consumers to become “prisoners to algorithms,” echoing the framing used in Renwu’s article.

Ultimately, this report demonstrates that rising dependence on the informal sector without social safety nets is likely to result in decreased wages and increased vulnerability for workers. In addition, by directing stimulus through businesses, including Ele.me and Meituan, the state is subsidizing the systems that oppress them, further concentrating wealth in the hands of a few major companies. With its focus on a sector that intentionally displaces risk onto workers, Renwu’s article vividly demonstrates the negative repercussions of inadequate social safety nets and weak protection for workers, as well as the growing and largely unchecked control of tech firms over the nature of reality and consumption itself.

–Chuang and friends

Delivery Riders, Trapped in the System

Behind a recent series of data briefs produced by the traffic police bureau is a broader discussion of how delivery work has become a dangerous profession.

Why has the platform delivery industry produced tremendous value in one area while driving social problems in another? To answer this question, our team at Renwu magazine undertook a half-year investigation involving food delivery workers from across the country, participants at all points on the delivery chain, as well as social scientists. In the course of this investigation, the answer gradually emerged.

In this long-form report, we attempt to provide an in-depth look at the detailed workings of the delivery system, encouraging readers to contemplate this question: Exactly what form should algorithms take in the era of the data-driven economy?

(At their request, all riders’ names have been replaced with pseudonyms.)

Order Received

Once again, two minutes disappeared into the system. Ele.me rider Zhu Dahe distinctly remembers the day in October 2019 when, gripping the handlebars of his scooter with sweaty hands, he saw the delivery time set by the system: “Two kilometers, delivery within 30 minutes.” He had been working delivery in Beijing for two years, and before that day, the shortest time he had ever been given for that distance was 32 minutes. From that day forward, he never saw those extra two minutes again.

At around the same time, Meituan riders also experienced a similar disappearance of time. One long-distance Meituan rider in Chongqing discovered that the delivery time for orders of similar distances dropped from 50 minutes to 35 minutes. His co-worker and roommate started to see a 30 minute maximum delivery time for anything within 3 kilometers.

This was not the first time that time “disappeared” from the system. Jin Zhuangzhuang was a Meituan delivery station manager for three years, and he distinctly remembers how from 2016 to 2019 he received “speed up” notifications from the Meituan platform on three separate occasions. In 2016, the longest time limit for delivering food 3 kilometers was one hour. In 2017, it was reduced to 45 minutes. In 2018, it dropped by 7 minutes, with a new maximum delivery time of 38 minutes. According to available data, the average delivery time across the industry went down by 10 minutes from 2016 to 2019.

The system that governs delivery services has the power to continuously consume delivery time. For the system’s creators, this is a praiseworthy advancement, a real-world embodiment of the deep-learning capacity of AI. At Meituan, the real-time smart delivery management system is called “SuperBrain,” while Ele.me calls their system “The Ark.” In a November 2016 interview, Meituan founder Wang Xing stated, “Our slogan is ‘Meituan: Send anything fast.’ Usually our deliveries will arrive within 28 minutes.” He went on to state that this is a good application of technology.

But, for the delivery riders tasked with realizing this technological advancement, this can be a nerve-wracking and even deadly experience. Among the variables evaluated by the system, delivery time is the most important metric, and missing delivery targets is strictly forbidden. Exceeding the delivery time limit results in bad reviews, pay cuts, and even dismissal from the job. In a message board for delivery riders, one wrote that delivery is a race with Death, a competition with traffic cops, and a friendship with red lights.

In order to keep himself always alert, one Jiangsu-based rider changed his social media username to “Being late is for losers.” One rider living in the suburban Songjiang district of Shanghai said he drives against traffic flow on almost every order, which he estimates saves him five minutes per delivery. Another Ele.me rider in Shanghai roughly calculates that if he followed all the traffic laws, the number of orders he could deliver in a day would be cut in half.

“Riders can never rely on their individual power to fight back against the times assigned by the system. All we can do is exceed the speed limit in order to make up for lost time,” a Meituan rider told Renwu. His most ridiculous experience was a one-kilometer delivery, to be completed in 20 minutes. Even though the destination was not far away, he had only 20 minutes to wait for the order to be prepared, pick it up, and deliver it to the customer. That day, he drove so fast that he was bounced out of the seat of his scooter several times.

Speeding, running lights, and violating traffic laws––according to Sun Ping, assistant researcher at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the delivery riders’ disobedience of traffic rules is a kind of “inverse algorithm.” Riders who have long been under the control and management of the algorithm have no choice but to use this labor practice. The direct result of this “inverse algorithm” is a sharp rise in the number of traffic accidents involving delivery riders.

In 2017, Sun Ping began researching the labor relations between delivery control systems and riders. While discussing the relationship between shrinking time margins for delivery and the growing number of traffic accidents with Renwu, she said it must be the most important cause. Real-world data strongly supports this assessment. In the first half of 2017, there was a delivery rider casualty roughly every two days, according to data from the Shanghai Public Security Bureau’s Traffic Police. In the same year, 12 delivery riders were a casualty of traffic accidents every quarter in Shenzhen. In 2018, Chengdu’s Traffic Police reported less than 10,000 traffic violations by delivery riders, 196 traffic accidents, and 155 casualties. Roughly one delivery rider violated traffic laws or was involved in an accident every day. In September 2018, Guangzhou Traffic Police reported 2,000 traffic violations by delivery riders, with half committed by Meituan riders and Ele.me taking second place.

#Delivery has become one of the most dangerous professions# — This hashtag has already been a trending topic on Weibo several times. In publicly available news reports, individual cases are more moving than data—in February 2018, in order to make up time, an Ele.me rider was speeding in a road prohibited to scooters and ran over Li Mouqiu, the Dean of Shanghai Emergency Medicine and one of the founders of the emergency departments at Ruijin and Huashan hospitals. Li passed away after one month in ICU. In May 2019, a Jiangxi-based rider hurrying to complete a delivery ran over a pedestrian, who ended up in a coma. One month later, a rider in Chengdu ran a red light and collided with a Porsche, losing his right leg.

Zhu Dahe, the rider whose hands were sweating because of his anxiety over the delivery time, also experienced an accident. In order to avoid a bicycle, he swerved and spun out on an off-limits sideroad, and the mala xiangguo he was delivering also went flying. At the time, the first thought that entered his head, even before the pain hit him, was “Oh no, I’m going to be late!”

In order to avoid criticism for a late delivery, he called the customer and asked them to cancel the order. He used his own personal money to buy the spilled order of mala xiangguo. At 80 yuan, he said it was expensive but tasted good, so he ate it. He remembers it to this day, because at that time he had just started the job and lacked experience. The more reasonable way to resolve the problem would have been to return the money for the spilled mala xiangguo to the customer and let them order it again. “That way, I still could have kept the delivery fee for one trip,” he said, “6.5 yuan, I remember it very well.”

Scooter wrecks happen far too often, but the main question is whether or not the food spills, and not the injuries to the rider. Zhu Dahe told us that when he was delivering orders, he saw countless roadway accidents. Usually, though, he would not stop because his own deliveries could not wait. Meituan rider Wei Lai’s experience is similar to that of Zhu Dahe. One afternoon this spring, Wei Lai and another rider wearing the same color clothing as him were stopped at an intersection waiting for the light to change. There were only a few seconds before the light turned green, but the other rider darted into the intersection. At the same time, a fast-moving bus sped through and the rider and his scooter went flying. He died on the spot. Wei Lai said he saw the badly mangled body in the middle of the road, but he did not stop at all. His own order was late. At that time, another order came in and the familiar female voice of the app’s delivery assistant chimed in: “Order! From ‘Point A’ to ‘Point B,’ please respond after the beep to accept.”

Heavy Rain

According to the algorithm’s parameters, after a rider has accepted an order, the system will begin looking for another order for the rider to complete. In 2019, at the global ArchSummit, Wang Shengyao, the senior algorithm expert on the team that developed Meituan’s delivery management algorithm, introduced the AI’s basic operations––the moment a customer places an order, the system immediately begins looking for the closest rider with the most direct route. After determining which rider to assign the individual order, the system will usually assign that rider a batch of three to five orders. Each order involves two tasks: picking up the food and delivering the food. If a rider is responsible for five orders, that entails ten tasks, and the system will consider 11,000 possible routes. It is possible for the system to simultaneously assign 10,000 orders to 10,000 people in one second, with each rider receiving the optimum route for delivery.

In the real world, however, it only takes a heavy rain to shatter this ideal. Delivery riders like rain, because there are more orders to run on rainy days. But if the rain is too heavy, the system can easily become overwhelmed with orders and the riders themselves are more likely run into problems.

Geng Zi, a Meituan rider in Hunan, experienced a particularly horrible rainy night. It was storming all day and orders were coming in like crazy, overwhelming the system. At every station, each rider had more than ten orders at a time. Their delivery bags were full, so they put the rest of the orders anywhere on their scooters that they would fit. Geng Zi remembers that he had to carefully rest his feet on the edges of the scooter’s footboard, balancing a stack of food orders where he would normally rest his feet. As he ran orders from one place to the next, he would constantly look down at the boxes stacked between his legs to make sure that they had not spilled. The roads were so slippery that he slid many times, but each time, he would immediately get up and continue on his delivery. He worked without stopping until two in the morning, and only then could he finish all of his deliveries. A few days later, he received his pay for the month. Shockingly, his pay was lower than usual. There was a simple explanation: on the stormy day, many of his orders were delivered late, causing his pay to be docked. Gengzi was not the only one to have his wages cut––his station supervisor was also penalized.

Eating data: That’s how Meituan delivery supervisor Jin Zhuangzhuang describes his position.4 For a station, the most important numbers include the orders accepted, the rate of late orders, the rate of bad reviews, and the rate of complaints. Of these, the rate of late orders is the most important because many complaints and bad reviews stem from delayed deliveries.

Usually, delivery riders’ rate of late orders does not exceed three percent. If a rider does not meet this standard, the station’s rating can decrease, reducing the whole station’s cut of the delivery fee for delivery, including the cut for the station supervisor, quality control, and other personnel responsible for internal management. Even the salaries of the district manager and the regional manager could be affected.

At the end of every year, stations must face assessments by the Meituan and Ele.me platforms. The stations ranked in the bottom ten percent of every region face the risk of being eliminated.

Under the system’s metrics, late deliveries not only result in reduced wages, but can also have an impact on riders’ mental health. It can make a rider feel like a team’s weak link. According to Sun Ping, late deliveries are very serious. Not only do they impact your paycheck, but also what’s left in your bank account, and they even have the possibility to call the honor of delivery teams into question. When a rider lets everyone down by running behind, the station supervisor talks to him first. After the station supervisor is finished, the neighborhood supervisor will come looking for him, and after the neighborhood supervisor has spoken with him, the district supervisor will get involved––supervisors at all levels will get in touch with the problem rider. In the end, nobody will like him anymore.

This can put incredible mental pressure on riders. Zhu Dahe, the rider who crashed along with an order of mala xiangguo, told Renwu he has dealt with depression every day of the past few months that he has been working as a rider. Zhu came from a rural area and was not familiar with roads in Beijing, let alone the massive flows of cars and people. He anxiously obeyed each and every traffic rule, and every day his pay would be docked because his deliveries were late. This made him feel incompetent––isn’t it true that every deliver rider makes more than 10,000 yuan a month? Isn’t anyone able to be a delivery rider? Why couldn’t he do it well? He said it seemed like he wasn’t delivery rider material.

Later, he became more comfortable riding the scooter and the roads became more familiar. As he transformed from a new rider to an expert navigator, that feeling of incompetency slowly went away, his late delivery rate went down, and driving against the flow of traffic no longer bothered him so much. He said that when he and his fellow riders are all going the wrong way at once, he is even able to feel at ease. Nowadays, Zhu Dahe rarely makes a late delivery, but extreme weather is a curse he cannot escape. At those times, the out-of-control system will wrap him up alongside everyone else––under the weight of the heavy order volume, he completely loses the ability to control his delivery times and still faces the penalty for late deliveries, without the option of taking a break to catch up or asking for the day off.

When Typhoon Lekima hit Shanghai in August 2019, an Ele.me rider was accidentally electrocuted in the heavy rain. Soon after, screenshots from a delivery station’s WeChat group chat were trending on social media. In the screenshots, the station supervisor told everyone, no one is allowed to take leave for the next three days… anyone who doesn’t show up for work will receive a double penalty for absenteeism. Under the message sent by the station supervisor was a long string of replies from riders, who indicated they had received the message by sending “1”.

This screenshot stirred up a huge controversy. Some netizens asked why Hema (a grocery delivery company), KFC, McDonalds, and other restaurants with their own delivery services were all able to stop deliveries during a typhoon, but the delivery platforms could not?

Meituan station supervisor Jin Zhuangzhuang was helpless to respond. Every time the weather turns bad, riders will ask him for leave, claiming that they have a flat tire, or that they fell, or they have a family problem––all kinds of reasons. But in order to preserve the station’s numbers in the face of a huge influx of orders, he must rigorously uphold regulations. Except for birth, death, illness, or death, riders cannot ask leave on bad weather days, and taking leave will directly result in a fine.

Stormy days are also the most tiring days for Jin Zhuangzhuang. He must stay in front of the station’s computer, constantly monitoring every rider’s position, taking responsibility for every order and the timing of every delivery. In his delivery station, Meituan’s regulations dictate that every rider can take 12 orders at a time at most. If a rider has more than 12 orders, the system will stop dispatching new orders. However, during bad weather or important holidays, when there is no chance of handling the sheer number of orders coming in, the system is most prone to collapse: there are some riders with multiple orders, some with almost none; there are some riders who receive orders at the same time going in opposite directions; the delivery time for nearby orders is longer than the orders that are far away…

Under these conditions, Jin Zhuangzhunag must play another role: manual scheduling.5 In this role, he can enter the system directly and transfer orders from Rider A to Rider B in order to balance the capacity. Even though the system cuts off at 12 orders per rider, manual scheduling does not have these limits: as long as a person assigns the orders, the number of orders that a rider is responsible for can reach an overwhelming number. Each rider can handle 26 orders at most; one station can have a maximum of 30 riders, meaning that in three hours a single station can handle 1,000 orders. One rider responsible for running orders in a smaller city of 500,000 people reported being assigned 16 orders at a time during peak hours.

As an Ele.me station supervisor told Renwu, this kind of manual intervention is not done on behalf of the workers, but rather in order to force every rider to operate at the limits of their speed and ability. If pushing his riders to their limits is still not sufficient to handle the orders, Jin Zhuangzhuang can deliver orders himself. The most he can handle at one time is 15 orders (a full complement). First he will let the riders handle the wave of orders by themselves, but if they still cannot handle it, his only option is to ask Meituan to limit the orders. “After 2018, our station was not allowed to ask for a limit on orders. Even if the order numbers were overwhelming, we still had to deliver them,” he said, “When there was an overwhelming number of orders, after finishing delivery everyone was numb. Everyone was running on instinct, without a human emotional response.”

Last year, Jin Zhuangzhuang left the industry because of a family illness. He said that personally he cannot go back. Recently he had some friends that wanted to run a delivery station, and he also persuaded them that this industry suppresses any human sense of time, and stresses data over people to a level you can’t believe without experiencing. During this summer’s heavy rains across south China, Jin Zhuangzhuang was glad that he had gotten away, but at the same time he couldn’t fully rest easy. He did not know how many stations were yet again overwhelmed with orders, or how many riders were working desperately to get their delivery numbers back up to standards.

Navigation

In her academic research, Sun Ping has contacted nearly one hundred delivery riders in the past four years. Many of these riders complained about the routes that the system gave them for delivering orders.

In order to allow riders to more efficiently deliver food, this intelligent system will replace the human brain to the greatest extent possible––by helping riders determine the best sequence for delivering food and giving directions for each delivery route, the riders do not need to use their own brains, they just have to completely follow the system’s directions. But at the same time, the riders run the risk of being led astray.

At times, the navigation system will show a direct route, [without regard for actual roads or traffic conditions]. A rider angrily told Sun Ping: “It (the algorithm) gives it predictions for time and distance as the crow flies. But when we try to deliver food, we cannot follow that route, we have to make detours and wait for red lights… Yesterday, when I was delivering an order, the system said the dropoff was five kilometers away, but in the end I drove seven kilometers. The system thinks we are helicopters, but we are not.” At times, the navigation will instruct the riders to go against traffic.

In October 2019, Xiao Dao, a delivery rider in Guizhou, posted on Zhihu about an experience with Meituan guiding riders against traffic. In conversation with Renwu he said, “I had been a rider for about half a year and had already been told by the navigation system to go against traffic many times. One time when I was delivering food to a hospital, I had to make a U-turn, but the route on Meituan navigation told me to drive against traffic once I crossed the road.” According to the screenshot he provided, the system told him to drive against traffic for nearly two kilometers.

“Even more impressive,” Xiao Dao said, “There are some places where there is no shoulder or sidewalk where I can drive against traffic. If there is an overpass, the navigation system will direct me to go over the overpass, even if it is an overpass that does not allow electric scooters. If there is a wall, it will tell you to go directly through the wall.”

In Beijing, the popular video blogger Caodao also experienced the same thing. In order to experience the industry from the inside, she worked as a Meituan rider for less than a week. What surprised her was that after she delivered an order, the directions from Meituan’s navigation were actually walking directions––walking directions do not distinguish the flow of traffic. Furthermore, the estimated time given by the system was calculated based on the shortest route, even if the majority of the route went in the opposite direction of traffic.

As Xiao Dao sees it, it does not matter if it is a route “as the crow flies” or against the flow of traffic – ultimately, the system has still achieved its objective, calculating the shortest and quickest route for the smallest delivery fee. If the route is short and the delivery time is fast, the system will have not only retained more customers on its platform, but also reduced the overall cost of delivery.

At the end of 2017, in an article introducing optimizations and upgrades to the platform’s intelligent delivery system, Meituan’s technology team also mentioned cost. The article explains that algorithm optimization reduces the platform’s capacity loss by 19 percent: Delivery volumes that previously needed five riders can now use only four. Finally, cost appears in the conclusion of the article: efficiency, experience, and cost are the platform’s three indices for optimization. Meituan gets significant real-world benefits from this approach.

According to public company data, the number of Meituan delivery orders reached 2.5 billion in the third quarter of 2019. The revenue for every order increased by 0.04 yuan year-on-year, and at the same time the cost for every order went down by 0.12 yuan from the third quarter of 2018––this also helped Meituan’s third quarter earnings in 2019, which in total were 400 million yuan.

Behind the substantial increase in the platform’s profits is a decrease in riders’ salaries. Xiao Dao said every time that the system’s navigation told him to go against the flow of traffic, he faces a dilemma from which there is no escape. If he rejects the navigation’s instructions to go against the flow of traffic, he has to take a longer route and runs the risk of a late delivery. If he follows the navigation, he puts himself at risk. No matter what choice he makes, the money he makes will decrease.

Every rider must balance the trade-offs between safety and pay. As a temporary participant observer, Caodao pinpointed the plight of riders: all delivery platforms strive to maximize profits, and in the end they will shift the risk to those with the least ability to negotiate: the delivery riders.

the path for delivery cuts across the median.

In conversations with Renwu, many riders repeated the same thing: There will always be someone willing to take the delivery. If you were not willing to run the delivery, then someone else will.

Before working as a Meituan rider, A Fei was a delivery rider for KFC. At most, he could deliver 600 to 700 orders in a month because of the limits of the store. The brand could only give the delivery company 12 or 13 yuan per order at most. Because of this, the commission for delivery workers was always 9 yuan. He characterizes that job as “standard”: that is, the pay did not rise, and every month the most he could make was 5,000 yuan. Finally, inspired by the rumors that delivery riders could make more than 10,000 yuan a month, he decided to leave KFC and work as a rider for delivery platforms.

At Meituan and Ele.me, riders are divided into two types: direct hires and gig workers. Direct hires are full-time workers attached to a specific delivery station with a minimum pay and fixed shifts. They receive orders arranged by the system and are assessed based on their rate of positive reviews and on-time deliveries. Gig workers are part-time riders with very low barriers to entry––a rider only needs a vehicle and an app. After successfully registering, a rider can start work immediately. These gig workers do not have a minimum pay and they can choose their own orders and reject orders that the system assigns them. However, if riders reject orders too often, the number of orders they can select will be limited. Gig riders are not impacted by negative reviews and complaints, but late deliveries come with a more harsh consequence: If deliveries are late by even a minute, the delivery commission is cut in half. Regardless of whether the rider is a direct hire or a gig worker, the rider and the platform do not have a formal employment relationship.

A Fei ultimately decided to join Meituan as a gig worker. Before 2017, he worked for roughly nine hours a day, specializing in long-distance deliveries. Every month his pay was about 10,000 yuan. The most he made in a month was 15,000 yuan. Low barriers to entry and high pay were the main reason that platforms were assured of a supply of workers.

According to sociologists, riders’ pay surpassed 10,000 yuan because of the special conditions at the start-up phase of delivery platforms. After a long-term investigation of the labor conditions of delivery workers in Wuhan, Zheng Guanghuai’s team at Huazhong Normal University’s Institute of Sociology found that with the end of platform subsidies, more and more riders entered the profession, and monthly salaries of 10,000 yuan became little more than a dream.

A Fei told Renwu that after working delivery in Beijing for a short time, he went to Chongqing for personal reasons, and his pay decreased, especially after the pandemic, when more and more people joined the profession. He even had a difficult time getting orders to deliver. One month, his pay did not even reach 7,000 yuan. According to the Meituan research institute’s “Employment Report on Meituan Riders During the 2019 to 2020 Pandemic,” 336,000 new riders registered with Meituan’s platform during the pandemic. The top source for new riders was factory workers, followed by salespeople. According to A Fei, riders can usually make the most money when it is particularly hot or cold. Most people are unwilling to make deliveries under those conditions.

Elevators

According to public statements by the delivery platforms, elevator wait time is a key factor in the system’s estimation of delivery times. In an interview with tech media platform 36Kr, Meituan’s delivery algorithm team lead He Renqing emphasized elevators’ role in delivery time: Meituan’s delivery algorithm specifically accounts for the time riders take to arrive at a certain floor, even to the point of investigating the speeds at which riders can go up and down elevators in tall buildings.

However, real-world complexity far outstrips the AI’s predictive ability. As A Fei, the rider who has been unable to make a monthly income of more than 10,000 yuan, says, “Waiting for elevators is one of the most painful parts of our job––extremely painful.”

In many riders’ eyes, waiting for hospital elevators is the most difficult. For A Fei, who has worked as a rider for four years, the worst experience was the wait for an elevator in Beijing University’s No. 3 hospital. That time, carrying seven or eight orders at a time to the surgery department of the No. 3 hospital during the peak of the lunch hour was a terrifying scene. “I remember it so clearly,” he says, “At the elevator doors, delivery riders were packed in together with doctors, patients, and their families. It didn’t look too good. I waited as the elevator came and went several times, and when I was finally able to push my way inside, everyone was packed together so tightly that I couldn’t breathe.” That day, after delivering one order to the hospital, the next six orders A Fei delivered were marked late.

Later, when he moved to Chongqing, elevators were just as much a problem as before. The Hong Ding International building, a 48-story commercial building that became famous among online youth, is a maze of thirty or forty small workshops and businesses crammed together on each floor. Imagine your panic at sending a delivery to one specific stall – although the building itself has seven or eight elevators, at peak hours tourists waiting to get into the building and delivery workers sending or picking up food line up together, and it takes about a half hour just to get in the door.

There is also the Chongqing Global Financial Center. This structure is 74 stories tall, but the whole building only has one service elevator open to delivery workers. Elevator resources are already strained during meal times to begin with. Another issue is the result of attempts to maintain the office building’s image. As A Fei explains, “We can only wait by the elevator for the people inside to make their way out, and the people outside to pack the elevator again. Waiting for the elevator takes ten or fifteen minutes, and coming down after the delivery is another fifteen minutes. One order takes so long, how can you avoid being late?”

Office buildings don’t allow delivery riders into staff elevators, delivery riders from Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Chongqing, and Hunan told Renwu. This situation is extremely common. On July 11, 2020, a popular Weibo user named Caodao published a video based on her experience as a temporary delivery rider. One moment in the video, when Beijing’s SKP mall didn’t allow her to enter, became a trending topic online, and sparked a broad-based online discussion about occupational discrimination. As Caodao sees it, however, the SKP incident is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to discrimination against workers in the delivery industry. In that short video, another moment which received much less public scrutiny centered on elevators.

“This made a deep impression on me,” Caodao says, “I go into a building to pick up an order, and inside, there are a ton of shops, and they’re all the kind that depend mostly on delivery. The building had another elevator, but the security guard didn’t let me on. He only let me use one elevator that was specifically designated for delivery workers.” As a new worker, just finding this elevator took quite a while for her––and then, she had to wait in line for the elevator with dozens of other delivery workers. The riders spontaneously formed two lines, leaving the middle empty for the riders coming out of the elevator. Caodao spent ten or fifteen minutes just waiting for elevators.

Besides office buildings, some high-end residential compounds are another kind of elevator-minefield for delivery riders. In these buildings, getting on the elevator requires a keycard, but customers are mostly unwilling to come down from their apartments. What they do instead is to have us stand in an elevator, and then call an elevator from their floor––but there is no guarantee that the elevator you’re in will be the one that they called. According to A Fei, many riders will climb more than twenty stories of stairs just to avoid a bad review from this kind of customer. A Fei, on the other hand, works on the crowdsourced side of the industry and doesn’t have to worry as much about the results of poor review scores. As a result, A Fei’s solution is: “If the customer lives on the 14th floor and I think it’s not worth it, what we come down to is, I’ll climb seven flights of stairs, they come down seven stories, and we meet in the middle. This way, it at least makes a little more sense.”

A Fei says that he’s seen innumerable delivery riders on the brink of emotional collapse at the doors to an elevator, sobbing or fighting, because there are too many people waiting and they can’t complete the final step of delivering an order. If you can cram yourself into the elevator, you’ve made it, but in reality, all you can do is stand by the door and wait. There’s nothing to do––all you can do is wait.

In order not to be late, some riders will mark orders as delivered while they’re waiting for the elevator. However, this is against the rules of the system, and riders can be fined 500 yuan if the customer complains, a Gansu-based rider tells us.

On this particular point, Ele.me is slightly more humane than Meituan, says a Guizhou rider, who explains that Ele.me’s system has a “report” function. If the rider reaches the destination but has to wait a minute or two for the elevator, he or she can hit the “report” function to make a note that you arrived on time before completing the delivery, exiting the building, and hitting the final “complete order” button.

Zhang Hu, a rider from Zhengzhou, has worked for Ele.me delivery as well as Meituan’s crowdsourced platform. Comparing his work experience under these two platforms, he says that Meituan really is more ruthless: Meituan’s delivery riders are nothing but a group of robots running orders to customers. But the number of orders isn’t that large for Ele.me, which doesn’t have a large market share in the area, and as a result riders can be a bit gentler and more polite.

Objective data also support his judgment. According to internet monitoring platform Trustdata, in the first half of 2019 Meituan controlled 64.6% of the delivery market. Based on order numbers, Meituan riders deliver 20 more orders per day than riders working for Ele.me.

Regardless of how hard riders work, however, the platform doesn’t consider it fast enough. Complain as he might about Meituan, Zhang Hu eventually decided to leave Ele.me and join Meituan because the platform was able to offer him a delivery volume that would have been unimaginable with Ele.me.

This is also why A Fei eventually decided to work with Meituan. Although his wages did decrease during the pandemic, he never felt too bad: Under epidemic prevention guidelines, many compounds didn’t allow riders to enter, and office buildings prohibited riders from entering. The result was that he no longer had to struggle for the elevator. However, following the reduction in epidemic prevention measures, more and more compounds and office buildings are lifting their prohibition on deliveries, and elevators have once again become a point of pain for riders.

As the new round of battles over elevator space was beginning, Caodao was completing the final cut of her video on her experience trying out life as a rider. In the final version, Caodao added a scene of herself waiting for the elevator and, in mid-July, told Renwu that the experience of waiting for an elevator made her feel like an ant.

Gatekeepers

In 2019, Li Lei, who lives in Zhengzhou, switched from Ele.me to Meituan, and transferred his role from delivery station chief to business development, where his primary role was to expand business partnerships with his delivery station. In order to bring more trendy shops under the jurisdiction of his delivery station, he would often go door-to-door, building and maintaining relationships with specific shops. At weekend peak delivery times, he would even set out stools at stores’ doorsteps. However, this had nothing to do with building relationships. Instead, it was in order to encourage shopkeepers to get food out faster.

Compared with the wait for elevators, the wait to pick up orders from shopkeepers is an even more painful bottleneck for riders.

The system continually improves itself in the name of “intelligence,” repeatedly shrinking the time allotted for food pickups––but shopkeepers’ slow pace in getting food out the door has always been an issue. In a public article, Meituan’s senior algorithm expert Wang Shengyao explains that even after analyzing the history of completed orders it is still very difficult to accurately predict how long it will take a shop to prepare an order. As long as the predicted preparation time is not correct, the food delivery ecosystem will continue to contain a random variable.

However, faced with the fixed nature of the required delivery time, those who bear the burden of mitigating this variable are the riders.

According to accounts by riders, there are many reasons why businesses are slow at preparing orders. Some shops are very popular, and at peak times can’t even keep up with dine-in orders, but managers are still unwilling to temporarily reject delivery orders. On the other hand, some proprietors of smaller businesses in less-popular areas are a bit more relaxed and lack a sense of urgency: Riders rushing to pick up an order arrive only to find the shopkeeper walking into their shop with ingredients they have just purchased. Some shops, particularly those selling noodles, will wait to start preparation until the rider arrives, in order to ensure that their products are as fresh as possible.

These difficulties are all compounded for the three most difficult types of food delivery: roast fish, stews, and barbecue. A rider tells Renwu: “The last time I accepted an order for soup, I got to the restaurant, but they hadn’t even started to stew it. I waited there while they simmered the soup for 40 minutes.” Another rider talked about a time he was so anxious that he lost it and started shouting at the older men manning the stove, thinking all the while, “Guys, get to cooking!” But the cooks were as methodical as always, completely unworried. After all, the money was paid when he received the order, and if the order was late, the cooks wouldn’t be charged.

The problem of slow preparation is unsolvable, says former Meituan delivery station chief Jin Zhuangzhuang. Through the evaluation functions built into the system, shopkeepers can submit low scores or complaints about riders, but riders have no way of evaluating shopkeepers. Sometimes, riders are forced to carry water for shopkeepers: Complaints that food is too hot, not salty enough, or that an order was missing vinegar, which ought to be directed toward shopkeepers, often end up in riders’ inboxes. Many riders have petitioned for these negative ratings to be removed from the system, but none of these appeals have ever been approved.

Resolving this problem ultimately falls on the backs of riders. In Jin Zhuangzhuang’s experience, riders have to go often and develop a relationship with small restaurants that are often slow to complete orders, sharing cigarettes or telling jokes to the shopkeepers in order to get their orders bumped up the queue. In larger restaurants, it’s generally worthwhile to build relationships with hostesses or staff who prep to-go orders, who can bump your order up via their intercom to the kitchen.

However, this can’t solve the root problem, and conflicts between riders and shopkeepers continue to take place. Because of problems with order preparation, a rider in Jinan got into a fistfight with staff at a Hi-Tea franchise, and in Wuhan, a delivery rider stabbed a clerk during a dispute, and the clerk later died of his injuries.

The problem of waiting for orders leads to significant conflicts, some that have even led to the police being called. When asked how to solve this problem, one delivery rider put forward a simple solution: Extend the delivery time. With sufficient time, everyone wouldn’t have to be so anxious.

But in reality, delivery times have become shorter and shorter, and among the voices pressuring riders, shopkeepers––one of the major consumers of riders’ time––often raise the loudest complaints.

When discussing collaborative arrangements with restaurants, Li Lei discovered that what received the most attention from shopkeepers was how fast riders could arrive. If the speed at which riders arrived to pick up orders didn’t meet the shopkeeper’s expectations, they would point it out to Li Lei, switch delivery stations, or end their relationship. There are often two delivery stations for the same platform near a popular business district, and restaurant staff can choose which station to work with. As Li Lei says, the considerations for these arrangements are simple: First is the delivery capacity of the station, and the second is the speed at which riders can arrive at the restaurant.

In order to keep relationships with restaurants that send out a large quantity of orders, Li Lei urges the workers at the delivery station to work faster and faster. On the other hand, if the business owner is slow at preparing orders and causes riders to be late, this influences the metrics for the station––but all that Li Lei can do is go and talk it over with the owners, or go himself to try to speed things up. However, going into a restaurant and speeding up preparation isn’t something that just anyone can do––it also has to do with whether or not the station staff has built a strong relationship with the restaurant.

Sitting at the door of the restaurant, Li Lei stares fixedly at the screen of the point of sale system that prints delivery order slips, unwilling to be distracted even for a second. Ding, an order pops up, but restaurant staff hear his voice at the same time: “Meituan’s here, we’ve got a Meituan order here.” As he says, you have to beat your opponent by starting from the very first second.

Coca-Cola and Peppa Pig

As a result of a conflict with a customer, Meituan rider Xiao Lin discovered a secret hidden within the system: The delivery time displayed on the customer’s end is different from that shown on the rider’s side.

At that time, he had just started working for Meituan through their crowdsourced model. He accepted an order and rushed to the shop to pick it up, but just as he had the order in hand, the customer’s bald-faced question arrived in his inbox: “Why aren’t you here yet? You’re late already!” Xiao Lin thought that the customer had no reason to be angry, because at that point, his own phone showed that he had about ten minutes to complete the order. When he made the drop-off, the customer started arguing about the time once again, and when the two of them both took out their phones to compare times, the customer’s phone showed an expected delivery time that was a full ten minutes faster than that displayed on the riders’ side.

After discovering this secret, Xiao Lin would call Meituan’s customer service hotline monthly. It has been four years, and although he talks to a different customer service agent each time, their suggestions are always the same: Explain to the customer that the time displayed in their app is nothing more than an expected delivery time.

This is by no means a problem unique to Xiao Lin: Many riders told Renwu that they had the same issue. As they see it, this is a way by which the system tries to curry favor with customers and generate a stable client base––but at the same time, it is a major cause of conflict between customers and riders.

In the face of this consumer influence, food delivery platforms that are hyper-focused on customer base and order statistics use algorithms to construct a power hierarchy. In this structure, customers are of paramount importance, and have an unparalleled level of power.

“Customers can make mistakes. Customers sometimes… I can’t even say it.” Wang Bing, delivery rider from Gansu, has a mouthful for customers. “Many people don’t even know where their own address is: They obviously live at number 804 but write down 801. It’s clear that they live at the south gate, but then they write in ‘north gate.’ Some customers order dinner but then somehow forget, and when you call them, nobody picks up, until they call you the next day asking, ‘What happened to my meal?’ … When ordering food, some people obviously don’t look at the address. In just a glance, I can tell, this address is wrong, it’s in another province… The thing is, customers don’t have to pay the price for their mistakes. If the delivery is late, the rider is the one who is punished.”

Sun Ping, who has spent a long time researching the difficulties of the delivery industry, has also discussed the extreme power that customers hold. In the delivery process, the customer knows almost everything about the rider––his or her real name, phone number, on-time percentage, how many times he or she has been tipped, when an order was picked up, what route the rider is taking to deliver the order, and how long until delivery. As the order progresses, the customer still has the right to cancel the order.

“They can see everything, the whole process, but we don’t know who they are. What’s more, if there’s a problem, we can’t cancel the order the same way they can,” a rider complained to Sun Ping. That same rider also shared a story of what happened when his order was cancelled.

“I had two orders in hand. One was 1.5km away, with 45 minutes remaining, and the other was 3km away, with 20 minutes left. I delivered the order that was further away first, but the customer with the closer order got mad because he saw my GPS location pass by his house without delivering the order. He got really pissed, cancelled the order, and put in a complaint with the platform.”

In Renwu’s investigation, some riders told similar stories: “Then, the customer turned around and asked the rider, “Aren’t you just delivering my order?”

As delivery times get faster and faster, the rating system for riders gets completely skewed. As the system grows increasingly rotten, customers have also gotten more and more impatient.

Jing Jing, who lives in Shanghai, admits that he has been spoiled. He is usually busy with work, does not know how to cook, and relies almost entirely on takeout food. He often orders food at cafes and small restaurants not far from his home. As he remembers it, it used to take about 45 minutes from placing an order to eating the first tomato in a Caesar salad. Generally to pass the time he would watch a 45-minute TV series while waiting. More recently, the wait time has been a steady 26 minutes, but on one occasion, the rider took more than 30 minutes to get there. This wait was unbearable for Jing Jing, who called the rider five times to remind him.

In 2017, a survey by the French research institution Ipsos investigated impatience among consumers in 12 Chinese cities. The results indicate that the development of mobile technology has allowed consumers to become increasingly impatient in multiple aspects of their lives. This phenomenon is particularly pronounced in economically developed areas, and among younger consumers; overall, consumers in Beijing were the most impatient in the survey.

Faced with increasingly impatient customers, delivery riders have to find all kinds of methods to appease them. On this point, Wang Bing also has a lot to say: When he has a series of orders in hand, all with comparable delivery times, he will deliver the most valuable order first, because customers who order high-priced delivery are more likely to get mad and less likely to listen to any explanation the rider can offer. “They’ll just go off all of a sudden, and say they won’t accept the order. If it’s a 100 yuan delivery, where am I going to get the money to refund it when they cancel?”

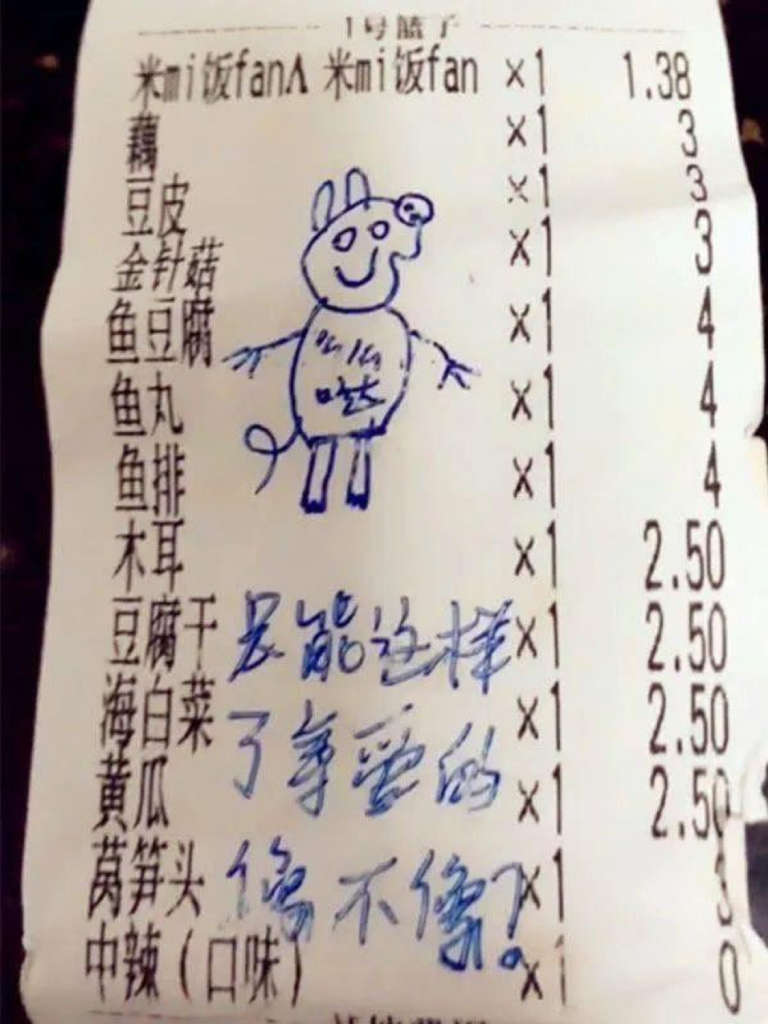

What’s more, riders have to try their best to fulfill customers’ particular demands about their delivery, such as purchasing water or cigarettes on the way to drop food off, or bringing shaving equipment to an internet cafe. There was a period of time when, following a Douyin (TikTok) trend, customers would often request Wang Bing to draw Peppa Pig on the delivery receipt, and give poor reviews if he didn’t. Wang Bing was quite angry about this, but had no choice other than to draw the picture, so he bought a sheet of butcher paper, drew a Peppa Pig cartoon, and wrote the tagline for another show – “Are you dumb?”

Delivery is a performance that puts the customer at the center. As Sun Ping wrote in a research report, ingratiating oneself with customers and striving for five-star ratings becomes a form of emotional labor. As she sees it, this emotional labor is often overlooked, but the effort it requires from riders and the damage it inflicts is far greater than that of physical labor.

When discussing the topic with Renwu, Sun Ping brought up one rider who had a deep impact on her: He had two scooters stolen from him in three days, and his scooter battery had been stolen three times. As she was interviewing him, he burst into tears: “The platform requires us to say ‘Enjoy your meal’ when we deliver an order. What nobody realizes is, I came from the countryside. Before this, I used to work the land. Saying ‘Enjoy your meal’ like this is really embarrassing––and then I have to ask for a five-star review. Me, a grown man, how am I going to say that?”

Just after the SKP incident, Shen Yang, associate professor in the Department of Public Economics and Social Policy at Shanghai Jiaotong University told an interviewer from news platform Jiemian that although some delivery riders can earn a monthly pay of over 10,000 yuan (about $1400), they still exist in an unequal class position, sacrificing their time and health in order to earn a bit more money. It is only by doing work that is more physically and emotionally difficult that riders can earn a higher pay.

Wang Bing is still continuing to develop new moves to appease customers. In the summer, many customers order a Coca-Cola to go with their meal, served in a cup. This year, with the heavy rain and the pressure to deliver fast, Wang Bing crashed his scooter relatively often – and even with the smallest crash, there was no way to save the cups of Coke. If he had to go back to the mall to pick up a new one, not only would he have to pay for it himself, but the order would definitely be late. In order to avoid angering the customer, he would always keep a bottle of Coke in his delivery box: If the customer’s cup spilled, he would simply find somewhere no one would see him, pour the new Coke into the spilled paper cup, and put the lid back on, leaving no trace behind. He figures that this is a great way to avoid issues.

At the same time, on a few legal counseling websites, a few anxious customers have posted questions: “If I call to speed up a delivery rider, who then gets into an accident as a result, do I bear the legal responsibility for the accident?” The lawyer’s response appears beneath the question: “You bear no responsibility.”

Games

Ele.me and Meituan recently published their financial reports for the second quarter of 2020. In the quarter, Ele.me managed to make a profit on every order, and Meituan was able to make a profit of 2.2 billion RMB, a year-on-year increase of 95.5%. During this period, delivery services were Meituan’s most profitable segment.

On August 24, 2020, Meituan’s stock price also reached a new high, with a market capitalization of over 200 billion US dollars, making it the fifth-most valuable company on the Hong Kong stock exchange. However, in the course of our half-year investigation, the 30 delivery riders Renwu met with were more interested in talking about nickels and dimes.

A Meituan rider in Hunan said, “If your on-time delivery rate dips below 98%, then you’re fined one mao (100 mao is equal to one yuan, with each mao worth less than a penny), and if your rate goes below 97%, you’re fined two mao. “Isn’t this more pressure on riders to speed up? Anyway, a penny per order really adds up for us.”

A rider for Ele.me in Shanghai said Ele.me’s lowest rate per order is 4.5 yuan, and the more orders you run, the higher the rate. Sometimes the extra penny feels really important––“when you’re looking at 4.9 yuan or 5 yuan, they really don’t feel that similar.” To keep that one cent, riders don’t just drive faster – they also drive more and more orders. This is an explicit goal of the system, and within it, there is another, hidden secret: a ranking game.

Meituan and Ele.me’s platforms both have a points system for riders. The more orders you deliver, the higher your on-time percentage, the higher your customer satisfaction, and the more points the system will award you. The higher your points, the higher your bonus income will be. The system has even packaged this ranking system in something like a role-playing game: Riders on different levels are given different rankings and names. For example, Meituan gives riders rankings of Normal, Bronze, Silver, Gold, Diamond, and King.

A Meituan gig rider who works in a southeastern city described the specifics of the ranking system: Within one week, delivering 140 valid orders with an on-time rate of 97% is enough to become a Silver ranked rider, which will earn you a weekly bonus of 140 yuan. If you are able to complete 200 orders with an on-time rate of 97%, you can reach a Gold ranking, and earn a weekly bonus of 220 yuan. For Ele.me, your order count is directly tied to your pay rate per order: If your monthly order total is under 500, you will earn 5 yuan per order; from 500 to 800, you earn 5.5 yuan; from 800 to 1000 orders a month, you will earn 6 yuan; and so on. Under the rules of the game, points are cleared and reset to zero every week for Meituan or every month for Ele.me.

In the research report “Orders and Labor: Investigating Algorithms and Labor in China’s Delivery Platform Economy,” Sun Ping shows that, besides creating an incentive system for on-time delivery targets, the system also uses gamified performance ranking measures to involve riders in a repetitive game that they have neither the time nor the ability to stop playing. “They want us to work day and night,” a rider told her. “But they [riders] have no way to get out: Last month, I hit “Black Gold” status, and if I want to keep that ranking, I still need 832 points––I’ve got a lot of work to do still.”

The higher your ranking, the more pressure a rider feels to maintain their ranking. As Sun Ping sees it, this kind of gamified packaging is not only a possible route to addiction for riders, it’s also a clever way to unite riders’ understanding of their self-worth with capitalist management techniques. The gilding of gamification generalizes algorithmic exploitation, internalizing it and giving it a rationalized explanation.

According to Meituan’s “Delivery Employment Report, First Half of 2020,” Meituan currently has nearly three million riders. Ele.me’s “Hummingbird” portal on its official website currently indicates that the company has 3 million riders. Faced with the existence of a system that now includes nearly 6 million riders, Central China Normal University sociologist Zheng Guanghuai put forward the concept of “downloaded labor.”

In an investigation report “Wuhan Delivery Rider Group Survey: Platform Workers and Downloaded Labor”, Zheng Guanghuai’s team of researchers expound upon the concept. Riders begin work by downloading an app. On the surface, the app is just a production tool for assisting their work, but in reality the riders are downloading a sophisticated labor control system. In this system, workers’ original subjectivity is comprehensively shaped and even replaced. Although platform workers may seem more independent on the surface, they are in fact faced with even deeper methods of control.

The platform is created through downloading labor: “Platform Workers”. As Zheng Guanghuai writes, “This type of labor is characterized by: strong attraction and weak contracts; high levels of management and low levels of resistance. The intermediary assisting the system in this downloaded labor is the workers’ own phones, which then become platform workers’ most important work tool. In their public reports, delivery platforms are always working hard to help delivery riders get rid of their phones.

“We worry that accidents will happen will happen while riders are on the road,” Meituan delivery management team leader He Renqing specifically mentioned during an April 2018 interview with 36Kr. For Meituan, the trickiest question is how to ensure that riders do not use their phones while driving. To this end, Meituan spent 7 months developing a Bluetooth headset with a built-in smart voice system. According to He Renqing, these Bluetooth headphones are windproof, waterproof, and noise-cancelling. While riders are wearing them, they can use voice commands to complete operational tasks, ensuring that they do not look at their phones while delivering food.

But in reality, none of the riders that we spoke with had received or used this smart Bluetooth headset, nor were they able to put down their phones. Although she only experienced the life of a delivery rider for a few days, Caodao still has a lingering fear of being controlled by her phone. “While the phone gives navigation advice, the system is always to one side, giving you reminders: ‘There are new orders in the Meituan gig app, please confirm immediately.’ These reminders are mixed in with the directions given by the navigation system. Then your delivery is late again, and maybe the customer calls you asking you where you are––then you might have to navigate and take orders and answer calls to explain why an order is late all at the same time…” Cao Dao told us that this kind of feeling forced her to think that every minute was very important, and every day was a harried flight from pursuit: You can only go faster, ever faster.

“We must never waste time on the road – that’s where time goes the quickest,” one Ele.me rider told Renwu. “An order is in your own hands just during the short time when you are on the road. Whenever there are a lot of orders, every rider wants to be able to take off flying––unless there is a traffic officer following right on your tail, saying ‘Don’t speed, don’t speed.’ He paused, and added: even flying is not quick enough.

At those times [when there are a lot of orders to run] the only help a rider can turn to is his or her electric scooter. Before starting to work for a platform, riders have to get a scooter. Usually, the delivery station will have a long-term contract with a second-hand company to provide riders with leases on electric scooters. In order to cut costs, most riders will choose to rent a scooter for a few hundred yuan a month. These vehicles are mostly in bad shape––some don’t have rearview mirrors, and some are only held together by tape, wrapped seven or eight times around the body of the scooter. One rider told us, “After starting to work in the delivery industry, I became an expert in electric scooter repair.”

If riders do not want to rent, some stations will ask to pay off the cost of their delivery vehicle in installments. One Meituan rider in Chengdu was required by his delivery station to purchase an unbranded vehicle at 1000 yuan over market price. Another rider said he spent several thousand yuan to buy an electric scooter through the delivery station, but the battery broke just two days later.

Compared to riders who were cheated out of their money, Meituan rider Wang Fugui feels lucky. Not only did he and the battery of his electric scooter both go flying on his first day of being a rider, his head got stuck in the guardrail alongside the road. The scooter itself was rented through the station for 200 yuan a month, and was basically stuck together from spare parts, with no lights and worn brake pads. Sometimes when he stepped on the brake, the scooter would just keep going, and when he tried to step on the gas, it would go backward. Still, none of these qualified as a problem. On the second day after his crash, he spent 10 yuan of his own money for a foot brake. When working at night, he would put a flashlight in his mouth to serve as headlight or glue it to the front of his scooter. “After all,” Wang said, “This scooter has its advantages. It was super fast––65 kilometers per hour at the fastest.”

According to 2018 data from the Ministry of Public Security, from 2013 to 2017 there were more than 5.62 million accidents involving electric scooters that resulted in injury or death, resulting in 8,431 deaths and 111 million yuan in property damage. In order to improve standards on the use of electric scooters, the country officially implemented new standards in April 2019, requiring scooters to be limited to speeds of 25 kilometers per hour. Any electric scooter that meets these new regulations will cost at least 1000 yuan.

Still, in Renwu’s investigation involving more than 30 riders, none of the riders had a scooter that met the new national standards, regardless of whether they worked for Meituan or Ele.me. Their scooters’ top speeds were typically around 40 kilometers per hour, far faster than the speed limit. Still, it’s easy to find discussions on how to refit newly purchased electric scooters to go faster than the speed limit in riders’ online discussion groups and message boards.

After he had worked as a rider for over a year, Wang Fugui’s broken-down scooter stopped working – went on strike – more and more frequently, and once or twice, Wang had no choice but to take a taxi to make his deliveries. Luckily, since he was in a small Northwestern city, when his scooter finally quit on him for good he was able to simply take a taxi to avoid late deliveries, spending 50 RMB to smoothly deliver ten or fifteen meals. Afterwards, in order to run orders faster, he gritted his teeth and spent his own money to buy a new scooter – as for his first, broken-down vehicle, no one can say how many parts were pulled off of it, or how many other rental scooters they were installed on.

Both on his old scooter and the new one he bought, Wang Fugui’s performance was always ranked in the top five, or even the top three, riders in the delivery area. However, after working for a short time, he eventually resigned because the platform’s new requirements were unbearable. “In order to expand its business, Meituan made us go out on the streets to pull in new customers. Every day we had to get two people who had never used Meituan’s app to register a new account. At the beginning, I was able to keep it up for a few days, but in the end, I decided I really couldn’t stand it, so I just left.”

Smiling Action

When the news that delivery driving was the most dangerous profession became a trending topic, the system was already making great efforts to counter the issue.

In the early days of the platforms, both Meituan and Ele.me provided safety training for riders, with a focus on the entry phase. Both professional and gig riders had to pass a simple safety and knowledge test in order to begin work.

Station managers often remind riders about safety issues. A Meituan station manager told Renwu that every time he did a safety training, he would make his own special compilation of electric scooter accidents for the more than 300 riders he managed to gather; after watching the video, he would reinforce the main messages: “I know you are all under pressure, and going against the flow of traffic is unavoidable, but please keep your eyes on the road.” This is also what an Ele.me station manager told us that he had reiterated many times. “Riders all put time first, rather than safety. There are times when they do not even value their own lives – in the end, what they fear most of all is being late.