Image: Protesters marching in downtown Saigon. The front banner reads, "Do not give the SEZs to Red China [Trung Cộng], not even for one day." Source: Kao Nguyen / AFP

From 111 BCE to 968 CE the territory around contemporary Hanoi was ruled by northern (“Chinese”) empires as “An Nam đô hộ phủ” (安南都護府): “the Protectorate General to Pacify the South.” Recently, the political memory of this “thousand years of northern occupation” (Nghìn năm bắc thuộc) has been reborn as an independent political force. On Sunday June 10th, popular opposition to planned Special Economic Zones erupted into massive nationwide protests. As of this writing, the SEZs have been postponed for “further research.” Nevertheless, this is the latest in a series of events that prove this insurgent popular nationalism is increasingly an obstacle, rather than an asset, to the ruling Vietnamese Communist Party (VCP) and its development schemes. In this post, Đã Thành Đồ Sơn digs below the surface to contextualize recent events in terms of widespread Vietnamese Sinophobia. A longer article in the forthcoming second issue of the Chuang journal will provide more background on this Sinophobia in the complex history of relations between these two polities.

—

长期稳定 – Trường kỳ ổn định — Long term stability

面向未来- Diện hướng vị lai — Facing toward the future

睦邻友好- Mục lân hữu hảo — Neighborly relations

全面合作- Toàn diện hợp tác — Comprehensive cooperation

— “The 16 golden words,”

meant to guide the renewal Sino-Vietnamese relations since 1990

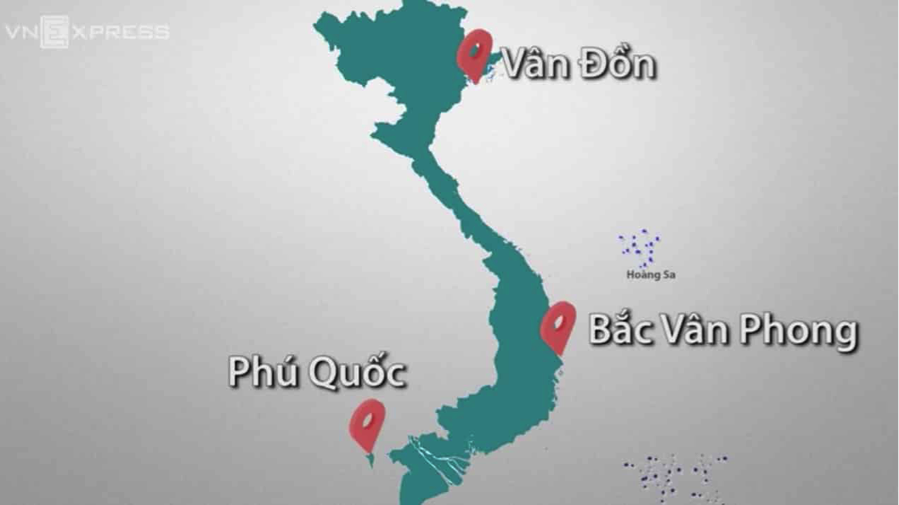

The plan for three new SEZs has been public since as early as May 2017, when Nguyễn Chí Dũng gave an interview with Reuters announcing three zones in Vân Đồn, Bắc Vân Phông, and Phú Quốc, with approval expected by the end of 2017. The zones would be “outstanding in everything: free and favourable in every aspect” and a “massive attraction to investment, and investment will boom next year.” The goal was to move up the value chain, saying “it’s no longer about quantity but more about quality.”

Location of the three proposed SEZs

Reflecting on whether administrating through “autonomus [tự chủ] special zones could be a magic wand, lifting Vietnam to the level of developed nations in the region,” a June 2016 Nhịp cầu đầu tư [“Bridging Investment”] article summarizes the early debate on the zones. The author estimated that by 2030 median wage in the three zones would be raised to $12,000 per capita. Furthermore, despite already having 18 nominal “special economic zones” and 325 “industrial zones,” these three new zones will be the first true SEZs separately administered directly under the VCP’s Central Committee and organized outside the provincial system. Foreign currencies might be used, separate laws might be administered, including legalized gambling, and businesses would be limited to a 10% tax for 30 years, with the first 4 years tax free and the subsequent 9 years at 50% tax. An attached table estimated revenue from the three zones as follows:

(1) Vân Đồn, estimated at $1.9 billion in taxes and fees per annum, $2.1 billion in real estate per annum, with $9.7 billion in value created by local business and 132,000 new jobs by 2030;

(2) Bắc Vân Phong, estimated at $1.2 billion in taxes and fees, a billion from real estate, $10 billion in new value created by local business and 65,000 new jobs by 2030;

(3) Phú Quốc, estimated at $3.3 billion from taxes, fees and real estate, with $19 billion in new value created by local business and 57,600 new jobs by 2030.

The article also held up China’s SEZs in Shenzen, Zhuhai, Shantou, Xiamen, Hainan, and the “Super Economic Zone” soon coming to Xiong’an as successful examples. Still, the author had concerns. “In reality, it’s not so simple as just establishing an SEZ, allocating huge budgets for infrastructure investment and favorable tax rates.” And allocating the necessary funds would be difficult for Vietnam. Acknowledging that more than 50% of SEZs in the world end up failing, and those that succeed take up to ten years to show results, the author argued that patient preparations would have to be taken to find the right strategic partners. “Special economic zones are where phoenixes lay eggs. If we make a chicken coop, there’s no way a phoenix will come lay an egg.”

All was going according to plan when, on August 2nd 2017, the Goverment Standing Committee held a meeting attended by Organizing Committee Chief Phạm Minh Chính, various chief ministers, and the provincial heads of the three zones. The Prime minister concluded that the law was well prepared and ready to be submitted to the National Assembly in the coming October.

Readers’ comments on an article about the meeting show that, as early as August 2017, but possibly earlier, the public was concerned about the SEZ’s becoming de facto Chinese “concessions.” For example the first comment, by Nguyễn Thành Luân, demanded that the authorities “carefully research the policy of permitting foreigners to own property […] in the economic zones. If not, these three zones will belong to China.” Twenty minutes later Đỗ Xuân Phong comments that “If China rents the land for 99 years, the Chinese will take Vietnamese wives and birth descendants, causing [the zone] to become a Chinatown.” Within twelve hours there were fifteen comments rejecting the plan on similar grounds.

Still, state reporting remained positive, with Zing VN putting out a slick video advertising the potential increases in revenue, reductions in taxes, and explaining the necessary administrative reshuffling.

So if not from state media, where does this concern about concessions come from? Regime opponents, both within the country and in the diaspora, have long framed Chinese-invested projects in neocolonial terms. The most exemplary case is the Chinalco-invested bauxite mining operations in the Central Highlands. The best analysis yet produced can be read here. In short, opposition to the planned project first arose in late 2008 on the grounds that the projects would devastate the environment and further marginalize the area’s already oppressed ethnic minority communities. Opposition exploded after General Võ Nguyên Giáp, a national hero subordinate only to Hồ Chí Minh in the official pantheon, published an open letter condemning the plans for risks to national security, arguing the proposed mines would actually be a forward operating base for the Chinese military. Opposition was mostly restricted to the lively Vietnamese blogosphere, and after some high profile arrests, the government went ahead with the mines. Which, it’s worth noting, have been plagued by failure.

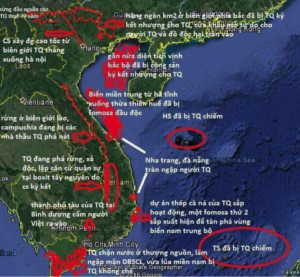

A meme mapping Chinese projects and military interventions, amounting to a Chinese siege of Vietnam

It’s certainly rare for a founding father like General Giáp to break ranks and give a public endorsement of such an extraordinary theory. And since Giáp died of old age in 2013, we’ll never know his thoughts on more recent Chinese-invested projects. Nevertheless, some iteration of the China conspiracy haunts them all. From the failing Hanoi metro project, to the Taiwanese Formosa Plastics invested steel plant, to any number of plants and mills that are spreading across the landscape, all are framed as the latest move in a millenia-long chess match wherein Viet independence faces off with timeless Han expansionism.

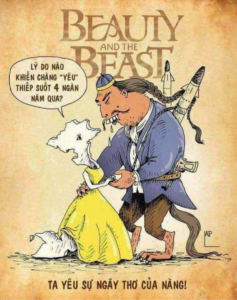

A Chinese “beast,” ethnically marked by his queue and facial features, woos a Vietnamese “beauty.” She asks, “What is it, prince, that has made you ‘love’ this maiden for these four thousand years?” He replies, “I’m in love with your naiveté!”

The recent South China Morning Post article about popular resistance to the planned Special Economic Zones is correct to note that memory of the Third Indochina War and the maritime dispute in the South China Sea are important markers for popular Sinophobia, but narrowly focusing on these two albeit pivotal historical events fails to account for perhaps the most important feature of Vietnamese anti-Chinese nationalism: unlike Chinese anti-Japan nationalism, Vietnamese anti-China nationalism always borders on being anti-government and is thoroughly beset by anti-Communist, pro-democracy activists.

Briefly, two basic versions of the conspiracy theory are prevalent throughout the country, both of which arise from the very real, though secretive, September 1990 Chengdu Conference. While Vietnam’s Communist allies were crumbling throughout Eastern Europe, and just after the CCP crushed “Tian’anmen” worker and student uprisings in cities throughout China, the VCP abruptly stopped the loosening of restrictions on speech and assembly, and closed the discussion of democratic reforms, to meet with Li Peng and Jiang Zemin in Chengdu and normalize relations. Less than two years earlier, Vietnamese naval forces lost the Spratly Islands to the Chinese Navy in the Johnson South Reef Skirmish, which is popularly remembered as a massacre wherein Vietnam suffered 75 casualties to China’s one wounded. For more than ten continuous years prior, the long tail of the Third Indochina War watched Vietnamese soldiers fighting and dying in ongoing confrontations along the Chinese border and in the Cambodian wilderness. But suddenly, after the Chengdu conference, no more mention was made of these wars and their “martyrs,” a new era of close economic collaboration suddenly replaced total embargo, and the recently tolerated and popularly celebrated critical authors, journalists and intellectuals were arrested, suppressed and exiled from the country. To many, it’s no coincidence that the sudden abortion of Vietnam’s brief flirtation with democracy during the Đổi Mới Era (“Renovation,” 1986-1990) was heralded by renewed relations with China.

![Another example meme. From top, "What do you all think? [from] The treasonous 1990 Chengdu Conference. [to] The Annam Autonomous Zone 2020??” From the Café Ku Bua facebook page, which has 115,290 followers.](https://chuangcn.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/vn-meme-5-300x225.png)

Another example meme. From top: “What do you all think? [From] the treasonous Chengdu Conference of 1990 [to] the Annam Autonomous Zone of 2020??” From the Café Ku Bua Facebook page, which has 115,290 followers.

Meme: “Three Special Economic Zones: The wolf walks step by step!”

The three planned Special Economic Zones, however, were not explicitly Chinese-invested projects, but rather were open for bid. Nevertheless, by May 23rd, when the proposal was submitted to the National Assembly for discussion, the plan was widely and vehemently opposed as an unacceptable capitulation to Chinese expansionist schemes. PhD Võ Trí Hảo compared them to a “second Crimea,” and internet petitions signed by thousands of reputed activists and intellectuals complained that the zones “are disguising many disastrous risks.” The Veterans’ Association, an especially influential quasi-official organization of more than four million members, officially protested the plan, citing Chinese state plots to send settlers and purchase land through citizen intermediaries. Those defending the plan point out that not only are the zones not restricted to Chinese investors, but also that the draft law does not grant the investors any legislative or judiciary privileges. Still others opposed the SEZs on less conspiratorial grounds, for example that SEZs were outmoded, unlikely to work, and that red tape should be lifted across the country instead of limited to these FDI zones. Nevertheless, the overwhelming popular opposition expressed in memes, blogs, and now over the past two days, in industrial strikes and street protests perhaps unprecedented for their size and scope, all make explicit connection to Chinese expansionism.

The government responded to growing public outrage by postponing the June 12th vote with promises to reconsider the plan and the lengthy 99-year lease. This already significant acquiescence did nothing to stem the protests already planned for the coming Sunday.

Agitational posts spread wildly in the run up to the weekend. For example, this one by Nguyễn Quang was addressed to all those who planned to “go protest, watch a protest, go for a walk in the park, or go drink coffee.” It warned protestors of the probability of police violence and state revenge against students, workers and business owners who may have their livelihoods destroyed by state blacklisting. Nevertheless he called on readers to protests, saying:

All have the right to choose the way they wish to live. But there are two things in life, of which we only have one. Those are youth and the fatherland! Live! Don’t just exist. Use your youth to write the heroic stories you’ll tell to your grandchildren. Live the life of a citizen. Be responsible to the place that has cared for us since we left the womb. Always remember, that we are hitting the streets because of China. We are hitting the streets for the Fatherland!

Pro-government, “anti-disinformation” and “anti-reactionary” Facebook pages agitated against the protests by sharing information of foreign involvement by reactionaries and remnants of the former Saigon regimes, and by comparing the events to the color revolutions in Libya, Syria and Ukraine, which are shorthand for Western plots to further geopolitical goals by cynically promoting democracy, destroying the host countries in the process.

On Friday a small march took place in Bình Thuận. And on Saturday, the workers at the Pouchen textile factory on the outskirts of Saigon went on strike and blocked State Highway 1, the country’s largest highway.

On Sunday morning, typically the “protest day,” rallies were held all over the country. A collection of videos can be viewed here. From chants of “99-year SEZ, object, object!” protestors moved into more militant language as the day progressed, such as “Overthrow China!”(đả đảo Trung Quốc) and “Overthrow the Cyber Security Law,” a new measure that will suppress anti-regime speech and greatly restricts the de facto freedoms afforded by Facebook.

Sunday afternoon, the police sought to repress the protests. In Saigon, as the protest approached the US consulate, uniformed and plainclothed officers beat and dragged protestors into specially made city buses with tinted windows.1

Nevertheless the march continued and reached a climax of sorts near the airport where protestors blocked the Lăng Cha Cả intersection and sang patriotic songs.

Significant resistance to police repression took place in the seaside province of Bình Thuận. Home to Chinese-invested coal plants that have polluted the ocean and destroyed the fishing economy, ethnic hatred has been further compounded by the fact that many of the impoverished local families have been forced into peddling services, including sex work, for the Chinese plant administrators and engineers. This local situation has no doubt added fuel to the fire there. Today protestors vigorously pushed back against police lines, routing the officers.

The protestors subsequently besieged numerous government buildings throughout the town, forcing the local government to flee.

Events are still unfolding, and it’s not yet clear if opposition to the SEZs and cyber security law will explode among workers the way broader issues did in 2014, when factory riots erupted in response to a Chinese oil platform that was dispatched to disputed territory in the South China Sea. What has already become clear is that, far from a tool in the government’s repertoire, Vietnamese Sinophobia is dominated by an anti-regime, anti-Communist, pro-democracy movement that wields considerable, though difficult to measure, power over domestic politics. If this analysis is correct, then a proletarian movement that is both anti-regime and anti-nationalist seems to have become nearly unthinkable in present-day Vietnam.

While episodic crisis and endemic inequality have fed nationalist populisms throughout the world, something uncannily similar appears to be happening in Vietnam. Here, however, the foreign enemy isn’t refugees or economic migrants, but the rising global powerhouse to the north. Once the chief patron of the revolution, when the two nations’ Communist parties were “as close as lips and teeth” (唇齿相依, as Mao famously put it), to many Vietnamese the CCP now embodies the worst aspects of imperialism and colonialism. How did this reversal come about? Look out for my article in the forthcoming second issue of the Chuang journal that attempts to make sense of this history.

—Đã Thành Đồ Sơn

Notes

- The video capturing this incident is tagged as containing violent content, so you have to log into Facebook before you can view it.

It is great to see the recent protests in Vietnam being addressed.

The Chengdu conference, as I see in a dissertation written by a student of Vietnam Academy of Diplomacy, was actually about concession of power and influence in Cambodia for final peace and stabilily with China. Of course the state’s secrecy does not help, but the conspiracy of Vietnam being annexed into China by 2020 is something that is lifted straight out of The X-Files.

Most anti-government organizations in Vietnam are pro-Western democracy. For example, Cafe Ku Bua, a Facebook page you quote in this article, is pro-Trump. Viet Tan is basically remnant of the South Vietnam puppet regime. Other pages that you used to quote videos are also on the same boat. Not saying that you can’t use their videos and stuff, it’s just for noticing the dominant trend of ideology in the anti-government side.

There is potential – in this protest, compared to 2014, the protestors called out the VCP and attacked police as well as storm local government buildings, which proved the ability to deal damage to the government. However, the workers’ movement is still rather scattered, not yet organized into a viable threat on its own, often ran by nationalist rhetoric and always ready to be hijacked by bourgeois opportunists (for example, a local conservative priest who happens to have enough influence).

Agreed Jason,

The footprints of local and overseas right wing, anti-communist radicals, with unclear relations to the US security state and media, are stamped all over Vietnamese anti-Chinese activism and the “Chinese conspiracy.” While the comparison to “color revolutions” is constantly thrown about by some of the more odious VCP apologists, a ‘kernel of truth’ no doubt lies in it. Wikileaks cables show what we may have already assumed, that the US embassy and consulate keeps close relations with pro-democracy activists.

Apologies if that didn’t come through clearly enough in the post.

hi Jason, can you tell me more about the origin of the Chengdu conference story? i’ve heard of it many times but didn’t know about the author.