The net is widening by the day for anyone who sticks their neck out for workers in China. Over the past few months, those who have voiced support for a network of silicosis workers from Hunan province have been arrested in two waves of coordinated police actions that ensnared NGO workers and left-wing website editors.

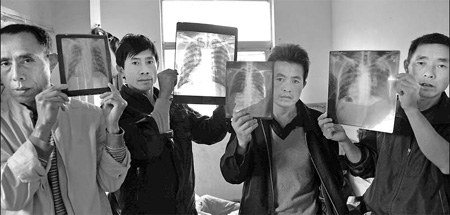

The network is composed of several hundred former construction workers suffering from silicosis (also known as pneumoconiosis or “black lung”) and their family members, from several counties in Hunan. The now elderly workers represent a handful of the estimated six million people in China with the disease, thought to be the most common occupational illness in China. Silicosis is commonly contracted by the inhalation of heavy particulate matter while working in mining or construction, where there is usually little to no adequate protection. In China, those with the disease rarely, if ever, have medical insurance, or the proof of employment needed to pursue legal recourse. In this case, the workers were drafted from Hunan in the 1990s to literally build the foundations for the Special Economic Zone of Shenzhen, blasting rock to build subways and buildings in the southern boomtown.

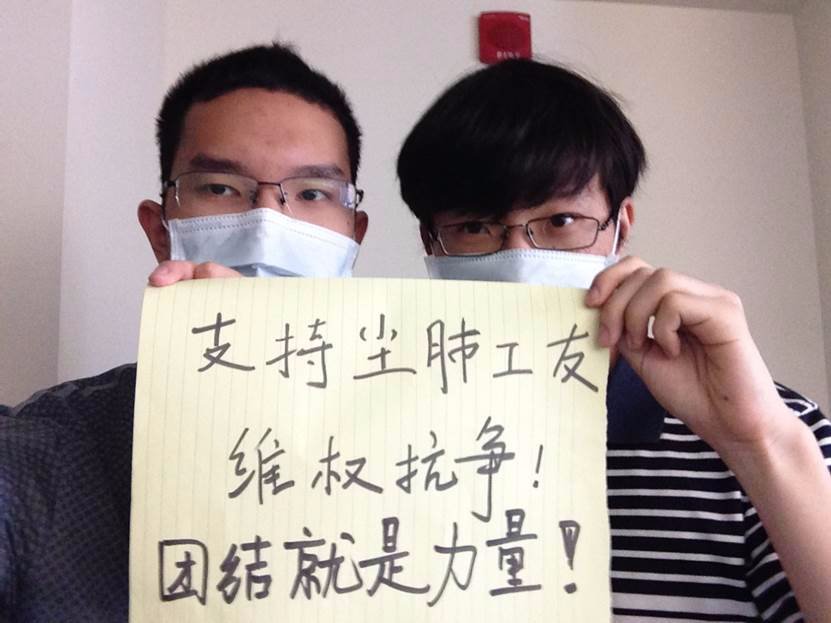

For years the workers have sought to obtain compensation for the heavy costs of the disease. At times, they’ve won small settlements. At others, they’ve been turned away by police brutality. All the while, many of them have died slow, excruciating deaths.1 Throughout these years, they’ve won the support of various NGOs and activist groups, but under the past year’s increasingly harsh state scrutiny over labor activists in Xi-led China, the workers’ supporters have suddenly found themselves in police custody.

The Hunan silicosis workers have repeatedly traveled to Shenzhen demanding compensation from the government for years of costly medical bills. It was shortly after one such trip last winter that Yang Zhengjun, editor of iLabour (新生代), an independent media platform oriented toward workers, was taken by police in Shenzhen, with his support for the workers reportedly being one of the main activities about which the authorities questioned him. In March two other editors, Wei Zhili and Ke Chengbing, were also detained.2

In late March, authorities stopped silicosis workers at a train station in Hunan, preventing them from traveling to Shenzhen to call for the activists’ release.3 The workers, however, continued to make such calls from Hunan, petitioning the All-China Federation of Trade Unions to intervene and holding a sit-in at a local government building.4

Another round of arrests came in May, when five other activists were simultaneously arrested in Beijing, Guangzhou and Shenzhen, their organizations searched and other staff brought in for questioning.5 At least one, Li Dajun, the director of Hope Community in Beijing, was questioned about his advocacy for the Hunan silicosis workers. Li had been a long-time supporter of the workers. In 2015, he wrote an essay titled “I Have No Choice But To Do This until I Die” (我没得选择,我只有做到死为止), telling of their struggles to pay medical bills and support themselves. In 2018, he penned “My Friend Killed Himself” about one of the workers.

One representative of the Hunan silicosis workers told Hong Kong news outlet iCable that the arrest of Li Dajun and the other activists in May likely resulted from their support for the workers’ campaign, and that Li had given them legal advice during one of their trips to Shenzhen.6 According to the report, others who worked at Li’s organization were questioned by police during the raid whether they had foreign ties, and whether they used “state subversion language” (顛覆國家言論).

Suspicion about the involvement of “foreign forces” has been a common thread in the repression of the silicosis workers’ network and their supporters. In January, when Yang Zhengjun was arrested, iLabour said in an editorial that police were investigating whether Yang had received foreign funding or was “conspiring with foreign forces.”7 The piece, titled “Please don’t insult my intelligence with your accusations about ‘foreign forces’, thanks,” was the last article posted on iLabour before it was shut down. It read:

I don’t know when it started, but there always seem to be evil forces surrounding our motherland. One moment they set up underground churches in order to incite unrest. The next they help human rights lawyers to “make trouble” in a bid to subvert the state. They then go so far as to usurp the banner of Marxism to sow confusion among Chinese college students. At the same time, they’re busy casting doubt upon the institutions of the national anti-corruption campaign. They pay off ride-app drivers to raise their consciousness. And from time to time, they maliciously short capital markets to cause disasters on the stock market … These mysterious forces capable of competing with Zhongnanhai [the headquarters of the CCP in Beijing] are the legendary “foreign forces.”

The article noted that Chinese Communist Party co-founder Li Dazhao was captured and killed by the Beiyang warlord government in 1927 for having “illicit relations with foreign countries,” fostering his communist politics. iLabour explained that the use of this bogeyman is a typical response on the part of “those with vested interests” used to distract attention from the social contradictions developing in China over the years, from laid-off state-owned enterprise workers to migrants working in sweatshops for foreign capital, to the lack of basic medical care for the nation’s six million workers suffering from silicosis. “Whenever there’s a social problem, it seems to be caused by ‘foreign forces.’”

Allegations of the black hand of “foreign forces” have been used liberally by the authorities in the Xi era, but they are becoming increasingly ridiculous as time wears on, with the forced closure of NGOs and activist networks of all stripes leaving pitifully few people or organizations that could even potentially have such ties. In the so-called “709” (July 9th) crackdown of 2015, over two hundred lawyers and human rights activists were arrested across the country. Several of them were charged with “subversion of state power” and accused of colluding with “foreign forces” in a plot to overthrow CCP rule, at least one eventually being sentenced to 4.5 years in prison.

At the end of that same year, dozens of labor activists were arrested in a nationwide sweep. In the ensuing propaganda campaign, alleged ringleader Zeng Feiyang was said to have used foreign funding to goad factory workers into carrying out strike actions. This narrative also linked several other local NGOs to “foreign forces.”8 China Labour Bulletin director Han Dongfang admitted that his group had funded some of the activists implicated in the crackdown, defending the decision in an open letter written to state media.9 When Zeng and others were finally charged, state media reiterated the role of foreign funding, but court rulings made no mention of that issue, instead convicting Zeng and others for “causing economic damages to the factory.” This shows that, on the one hand, it’s legally difficult to make allegations of foreign funding “stick,” even when there is ample evidence, but on the other, such accusations are often used as a public relations pretext for smashing up existing networks and giving authorities carte blanche to conduct wide-ranging campaigns against networks that the state considers threatening or troublesome.10

Last year, police leveled accusations of intervention by “foreign forces” at a completely homegrown networks of Maoists connected to the Jasic affair.11 State media agency Xinhua targeted the Hong Kong-based organization Worker Empowerment for funding a mainland NGO that allegedly supported the workers, a claim that Worker Empowerment denied.12 This charge, however, quickly faded into the background as more than a hundred workers, students and other leftists were arrested on other charges throughout the year since summer 2018, with over fifty still in custody and at least ten more arrested as late as July 2019—now with the default initial charges often escalating from “picking quarrels” to “subverting state power.”13

Below is a revised translation14 of the rap song “To Live” by X$core15 about workers from Hunan slowly dying of silicosis, followed by our translation an essay (coincidentally written by Jiang Xia, author of another piece translated on this blog, “The Harsh Winter of Your Employment Safeguards the Economic Growth of the Nation”) recounting their decades-long struggle for compensation. The song is said to have been based on a poem by the arrested iLabour editor Wei Zhili.16 The lyrics were published along with this essay last May on the independent left-wing platform Tootopia. A year later, Tootopia was shut down and its editor detained around the same time as silicosis worker advocate Li Dajun, as part of the broader crackdown on leftists and labor activists since the Jasic affair. It’s still unclear exactly how the arrests of silicosis workers and their supporters are related to this broader sweep in general, or to other specific targets like those associated with Jasic. For now all we can say is that the state’s intensified repression and surveillance, with its paranoid allegations of “involvement with foreign forces,” has become enough to deter almost anyone previously willing to stick their necks out for workers.

To Live (活着)

X$core

Music: Tonight We Eat Fishballs (今晚吃鱼丸)

Lyrics: Xu Haoyu (徐浩彧)

Verse 1:

Oh, he once yearned to come to this city

也曾带着美好憧憬来到了这座城市

once dreamed of earning an apartment for his family and child

也梦想过能给家人和孩子挣下一套房子

Today he can only drag his broken frame to face a heartless reality

如今只能拖着残破的身躯面对无情的现实

The jackhammer sprays grit that will corrode his lungs

风钻溅出的沙子 将他的肺部侵蚀

How helpless, put on house arrest for seeking help, left with just a diagnosis,

多么无助 求助却被拦在了住处 一纸诊断书

It’s like his lifespan has already been decided

仿佛已经宣布了他的生命长度

It’s ridiculous, wages earned by blood and sweat go unpaid. A strange state of affairs

无缘无故 血汗钱被拖欠 奇怪的名目

Under pouring rain, there’s no escape, but the boss lives in excess

大雨如注 走投无路 老板却在荒淫无度

Every day he leaves the tunnel, his dusty body reeks of silica

他每天走出井窑 身上布满粉尘的味道

Only to eat a dinner made with waste oil, grudgingly spooned out

地沟油做出得晚餐却舍不得多给一勺

He laughs bitterly, with the other workers all he can do is hold his tears and mess around

他苦笑 只好和工友含着泪打闹

His only goal is to see the next morning’s sunrise

能看到第二天早上的太阳是他最大的目标

It’s nonsensical, he is still collecting what they call evidence

多么可笑 他还在收集所谓的证据

He doesn’t know, in the government they only want evidence of their own achievements.

他不知道 有些个领导只要政绩

He gave everything, to build this city,

为了这座城市的建设 他 付出了无数

Only to become what they call a negative influence on public order

却成为了 人们口中 影响治安的因素

Hook:

Life is suffering, tricked by fate again and again

活着就是折腾 一次次被命运捉弄

These cold people can’t be persuaded of how his heart aches

冷漠的人不会被说动 他的心在隐隐作痛

Screaming social inequality, the words stick in his throat

感叹社会不公 想说的话都噎在了喉咙

Smiling as best he can, his tears fall into empty air

勉为其难的笑容 男人的眼泪洒在了空中

[Repeat]

Verse 2:

Countless times, he’s wanted out of this city

他无数次的想要逃离这座城市

Facing him is a cold reality:

面对他的却是冷漠无情的现实

He can persist no longer. He feels a weakness that had never existed before

他不再坚持 因为感到前所未有的弱势

Now he’s risked it all, only hoping to get people’s attention

孤注一掷 只希望得到一些人的注视

Hands that were once strong now tremble constantly, he struggles

曾经有力的双手现在止不住的颤抖 他战斗

The sickness has bowed his head, making him too weak to strike back.

疾病让他再也无力还手 低下了头

He’s wanted to end this suffering, but when he turns his head

也想过结束这一切的忧愁 突然回首

He sees his family and child are still behind him

发现家人和孩子还在身后

His time is short now. He just wants to leave his child something

他的时间不多 只想给孩子留点什么

But he realizes after all these years, he has nothing.

却发现了这么多年自己身上没有什么

When a person dies, what can those he loved rely on?

一个人走他爱的人还能靠什么

He’s long known this feeling, wanting to die but unable to leave.

他早已习惯这种感觉叫做求死不得

He sleeps, sleeps with a silence that has never existed before

他睡着了 睡得前所未有的安静

A cool breeze blows without stirring a ripple, he is gazing across mountains and rivers

清风徐来水波不兴他看到水秀山青

And it’s the first time in this place he has felt peace

这是他在这里第一次感觉到安宁

How he hopes it could stay like this and never awake.

他多希望这样一直下去 再也不醒

[Hook]

Rapping for Silicosis Workers:

This Time, Hip-Hop Has Truly Returned to Its Underground Roots

By Jiang Xia (江下的老马)

Tootopia, 8 May 201817

Recently, a group of workers suffering from silicosis arrived in Shenzhen from three counties in Hunan – Sangzhi, Leiyang, and Miluo. After having seen various government departments repeatedly shift responsibility, the arrests of several petitioners by riot police, and long meetings convened by various officials, the Shenzhen city government has still failed to respond to the petitioners’ appeals. All of these workers were drillers in Shenzhen in the past, and contracted silicosis, an eventually fatal occupational disease, as a result of this work.

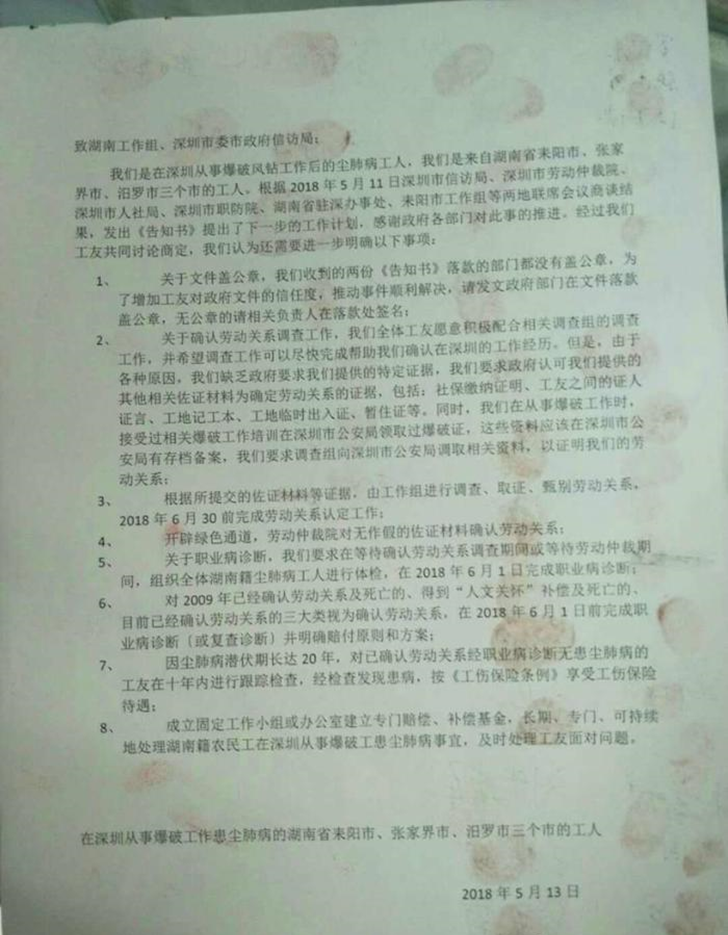

Early in 2018, the suffering workers came to Shenzhen to fight for their rights. However, before the ink from the 170 workers’ thumbprints on the official petition had dried, the leadership of the local complaints office arrived to urge the workers to return to their homes. As the workers describe it, this official’s words were very appealing, but devoid of any real response to key issues the workers had presented. In reality, the previous instances in which the workers had come to Shenzhen to petition for their rights had all ended with workers being returned to their homes.

As to the workers’ petition, the Shenzhen city government has always maintained that workers should follow appropriate legal proceedings. On May 11, the Shenzhen city government’s complaints bureau issued a decision document, which insisted that workers should follow legal procedures, but did not clarify a compensation scheme, and made absolutely no mention of how compensation could be established for workers with no clear record of employment relations.

The workers found this response to be extremely unfavorable. First of all, if workers were to follow legal channels, the entire process would be based on establishment of a formal employment relation. But, due to a long history of insufficient supervision on the part of the Shenzhen government, most of the workers on Shenzhen construction sites had never been offered formal labor contracts, and lack the paper trail of contracts, social security payments, and other effective measures for proving their work history in the city. As a result, following the official legal process would be prohibitively difficult. In addition, workers expressed that the timeline established in the complaints bureau’s response was excessively long, serving as an obvious delaying tactic. In the meantime, the workers’ health would continue to worsen, adding additional constraints to their already precarious economic situation. In this context, the workers’ attempts to protect their rights would be put at a significant disadvantage.

Nevertheless, this response reflected a change in the government’s attitude. On May 8th, as the workers continued to pursue their rights in a reasonable and legal way, always following complaints procedures, hundreds of police and affiliated security forces carried out violent arrests of many of the workers, with total disregard for the health of the arrested who were suffering from severe lung disease. Some workers were shoved to the ground and injured, with five or six requiring hospitalization. However, the protesting workers managed to continue collectively occupying the main hall of the complaints office until midnight that night, when the police released their six co-workers. These workers’ persistence pushed the government to change its tune somewhat over the following two days, when they began to actively negotiate with workers.

More recently, however, the Shenzhen government has tried hard to push the workers home, sidestepping major elements in the case and quibbling over minor details in ways that seem designed to obscure the potential outcome of these workers’ struggle. This song, “To Live”, was conceived as something to give to the workers, after the authors began to follow their struggle, in hopes that music can bring more people to pay attention to this group of workers.

Why should the Shenzhen government be held responsible?

Since the 1990s, a large number of workers from the villages of Sangzhi, Leiyang, and Miluo, in Hunan, entered into the drilling and blasting industry. The requirements of Shenzhen’s rapid development and frantic pace of construction attracted large numbers of construction workers to work in Shenzhen, and the fact that the city was situated over a large bed of granite created a great demand for a large number of workers in the drilling and blasting industry.

This industry has a prodigious risk of occupational disease. Drillers often have to work in tunnels thirty or forty meters underground, and pneumatic drilling of granite in particular produces large amounts of dust. Labor contractors often overlook safety protections for workers, and the local government has no supervision in place. Often, workers wear only a light medical mask for protection. As this terrible working environment began to cause many workers’ health to deteriorate, they quickly learned a new term: Silicosis.

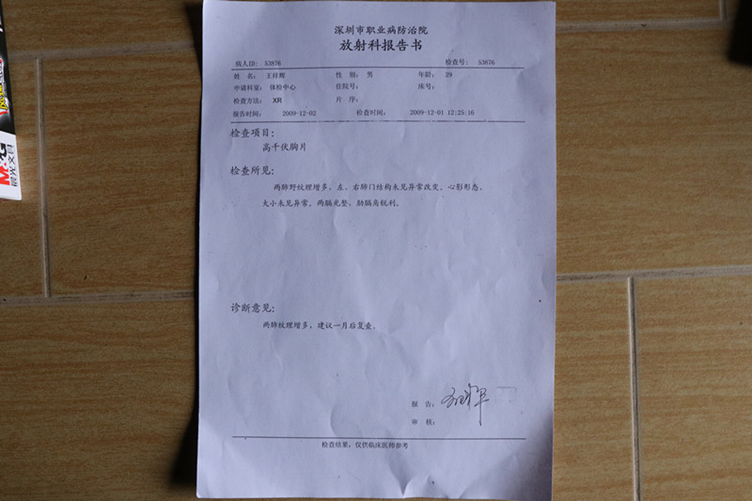

In 2009, over 150 workers from Leiyang, as well as Sangzhi County in Zhangjiajie, began to agitate for their rights as sufferers of silicosis contracted while working in Shenzhen. They demanded that the Shenzhen city government provide them with an occupational disease assessment, and provide compensation based on the results. According to China’s Occupational Disease Prevention Law, workers must provide a certification of their labor contract to the Occupational Disease Court before the Court can carry out an assessment. However, the construction industry has long been based on a subcontracting system in which large numbers of construction workers have never even signed any form of labor contract, not to mention the lack of payments into the social insurance system. As a result, it is very difficult to provide written records proving employer-employee relationships.

Unlike today, however, the workers’ actions attracted mainstream media coverage at the time. The Shenzhen city government rolled out the red carpet for these workers, and provided silicosis assessments for the over 150 workers who were active at the time. The results demonstrated that about 40 of the workers showed signs of varying stages of silicosis. At the time, the resolution offered by the city was as follows: Of those workers who were diagnosed with silicosis, those who had formal employment contracts would pass through official legal channels, and those who did not have formal employment contracts would be granted between 70,000 and 110,000 RMB in “humanitarian care” funding from the city government’s coffers, based on the severity of their illness.

Nevertheless, in 2017 when the Hunan provincial government investigated provincial silicosis indicators, the investigation revealed a large number of new cases. According to statistics, Sangzhi County in Zhangjiajie is home to 300 individuals who were either diagnosed or suspected to suffer from silicosis, in addition to nearly 200 in Leiyang and over 40 in Miluo. The great majority of these workers had worked in Shenzhen, and had stopped working as drillers since 2009. In reality, due to the long latency period of silicosis, many workers who were unable to be diagnosed with the disease in 2009 now show lung irregularities associated with silicosis, despite having never been diagnosed.

More recently, workers who were re-diagnosed as suffering from silicosis have again gone south, asking for a response from the Shenzhen city government.

On the eve of the Spring Festival, these workers from Hunan began the 2018 campaign for their rights. At this time, the situation was similar to that of 2009, as the largest stumbling block was still the certification of employer-employee relations, followed by the authentication of their diagnosis with silicosis. This indicates that for a large number of workers, there was no way to express their power through the process of legal petitions or suits. At the time, they received a spoken promise from the city government representatives: After the Spring Festival, Shenzhen would organize a working group to go directly to Hunan and resolve the issue. However, after the Spring Festival, the working group that the city government sent in April continued to insist that the workers gather and present proof of their employment relation and pursue legal action, just as before. In the brief span of these two months, three workers passed away, unable to wait for the results of the petition.

April 18th marked the second time that the workers’ group arrived at the Shenzhen complaints office. But, on the morning of April 19th, while they were quietly waiting for a response, what awaited them was actually a riot squad. The workers had been divided and sent to different places, and the government had even provided a lawyer for each worker, who invariably demanded that the individual workers resolve the issue through legal channels. However, this attempt to safeguard their rights made no headway whatsoever. Through various channels, the Shenzhen city government recognized the labor contracts of less than one tenth of the workers, but by April 27th, a large group of the workers found that the money they had brought with them was running out, leaving them without enough money to buy food. With no other options, they agreed to take the government-provided bus back to Hunan.

In the following period, the Shenzhen city government still had not responded to the workers’ demands. On May 8th, the workers once again steeled their resolve and headed for Shenzhen once again. This time, however, upon the moment they arrived in the city, they faced the events described above. All this is still taking place.

What’s Behind the Protests?

Most of the workers suffering from silicosis are adults in their prime, and the main supporters of their families. After getting sick, most are no longer able to undertake physical labor, and as a result, their families have lost their primary source of income. Apart from this, the medical costs associated with treatment for silicosis are exorbitant, despite the fact that the disease is ultimately incurable. Every time a worker suffering from silicosis is hospitalized, the medical costs exceed 10,000 RMB. Under heavy economic pressure, many families find themselves broken, buried under mountains of medical debt.

Furthermore, some of the workers who were examined in 2009 and not diagnosed with silicosis found that their symptoms worsened during the intervening period, and actually passed away prior to this rights defense campaign. Among them, a significant number committed suicide. According to a report on the subject, 37 people died as a result of silicosis between 2009 and 2015 in Leiyang County, Hunan. Among these, at least nine committed suicide because they couldn’t bear the pain associated with the symptoms of silicosis. Each of these deaths left behind an increasingly impoverished family.

Li Wanmei was “just skin and bones,” kneeling on the bed in his underwear, his arms supporting his body, his head propped up by pillows. An electric fan was placed next to him, but he had trouble breathing and was sweating all over. “As if water was pouring out of his body.” Li Wanmei had not eaten or slept for several days, he just kept kneeling in the same position. Less than a month later, Li Wanmei died kneeling in his bed.

In Tonglin village, Daozi county, one day during the 12th lunar month of 2011, silicosis victim Wang Congcheng couldn’t bear the torment any more. He used scissors to pierce his throat, then stabbed his abdomen and placed his hands into a water container while holding a power strip. He died the following day.

Cao Manyun was completely emaciated, weighing less than 35 kilograms. His face was flushed and he couldn’t stop coughing. On the road back to Leiyang, Cao Manyun told his brother, “I can’t bear it any more, buy me a bottle of pesticide”.“Hold out a little longer, I’ll buy it for you after New Years,” Cao Bin said to calm his brother. After returning home, Cao Manyun was hospitalised in the Leiyang Central Hospital. The next day, he jumped out his seventh floor hospital room. At that time, eldest brother Cao Jin had just returned from being hospitalized in Changsha. He shed endless tears, but as it was so hard for him to breathe, he spent a long time inhaling oxygen before he was able to cry. On an afternoon in April this year, Cao Jin decided to [commit suicide by] drinking pesticide.

[From a newspaper article translated into English here]

“An Investigative Report on Silicosis in Leiyang, Hunan: Numerous Painful Suicides”

These workers continue going through ordeals, facing hardships ranging from their illnesses, to economic conditions, to attempts by the state to divide them, to the mainstream media’s distraction from their case. After all, the Shenzhen government can put off justice, but these workers cannot wait any longer.

Under the crushing poverty brought on by an incurable disease, these workers are still the builders of Shenzhen, sacrificed in the name of development. These silicosis workers’ demands are for nothing more than that the Shenzhen government take responsibility. So far, good-hearted people can still see them before they are gone forever. Amid can ever-narrowing space for online discussion, people are contributing funds and writing songs for them — not to mention raising protest signs in support. Some kind-hearted passers-by even offered food, and sang for the workers during their protests. But, will the Shenzhen government take advantage of what little time remains to help resolve their problems?

Notes from translators & editors at Chuang

- China Labour Bulletin is one of several NGOs that has followed the campaign of this particular group of workers. One case of police repression is outlined here: “Shenzhen police use pepper spray on protesting pneumoconiosis workers,” 9 November 2018. Also see Wildcat’s overview of this case in our blog post “Winter is Coming: China 2018-2019.” CLB also has a number of longer English reports on silicosis and the campaign of the Hunan workers, such as “Time to Pay the Bill,” 2012.

- The Made in China journal translated an essay by Wei’s wife and prominent left feminist Zheng Churan (Datu), detailing the circumstances of the disappearance of the iLabour editors: “Separated Again by a High Wall,” 8 April 2019.

- “Police block workers showing support for detained activist Wei Zhili”, 29 March 2019, <https://clb.org.hk/content/police-block-workers-showing-support-detained-activist-wei-zhili>

- “Hundreds of Hunan Silicosis workers petitioned to support the criminally detained iLabour editors!” April 2019, Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions.

- “Three more people detained as China continues to crack down on labour groups,” 12 May 2019, South China Morning Post.

- “Another volunteer assisting silicosis workers has been arrested”, 10 May 2019, iCable Facebook, <https://www.facebook.com/cablechinadesk/videos/vb.265944843550009/458857331586145/?type=2&theater>

- 《请不要再用境外势力来侮辱我的智商了,谢谢》, 17 January 2019, iLabour.

- The best overview and analysis we know of is “Making Sense of the 2015 Crackdown on Labor NGOs in China” by Shannon Lee, Wolfsmoke. Also see our own earlier analysis “Theses on the December 3 Crackdown.”

- “A letter to the People’s Daily on China Labour Bulletin’s work with labour activists in China”, 12 January 2016.

- For further analysis, see Anita’s Chan’s take on the role, and risk, of foreign funding, and ties to organizations like China Labour Bulletin, among China’s labor NGO staff:

“The Relationship between Labour NGOs and Chinese Workers in an Authoritarian Regime,” Anita Chan, Global Labour Journal, 2018, 9(1). - On the Jasic affair and related left networks and repression, see: “Preliminary thoughts on the Shenzhen Jasic events” by Shannon Lee, Wolfsmoke, and the first two posts of our series “Seeing through Muddied Waters”: “Jasic, Strikes & Unions” and “An Interview on Jasic & Maoist Labor Activism.”

- “Hong Kong labour rights group denies mainland Chinese media report claiming it helped organise Jasic Technology strike,” South China Morning Post, 28 August 2018.

- For a dynamic English timeline and list of those arrested, their charges, current status, etc., see the “China Labor Crackdown Concern Group” website, including its “List of the Summoned, Arrested and Disappeared Since July 2018.” We focus on use of this rhetoric in the mainland here, but the widespread emphasis on “foreign forces” in mainland narratives about ongoing protests in Hong Kong should also be recognized.

- We made some minor revisions to the translation of the song already posted on Youtube. Thanks to Tomrade for uploading the song and posting the lyrics. (The translation of Jiang Xia’s essay is our own.)

- We haven’t managed to find any information about the rap group X$core — the name seems to have just been used for this song when it was published on a Chinese platform from which it has since been taken down. The lyrics are credited to Xu Haoyu (徐浩彧), a name we haven’t found anywhere else associated with hip-hop, and the music to “Tonight We Eat Fishballs” (今晚吃鱼丸), a producer with quite a few tracks online with other rappers, none of them particularly political as far as we’ve noticed. In the comments under this song on Netease (from where it has also been taken down now), someone said the lyrics were written by the detained activist Wei Zhili, but someone else replied that actually rapper Xu Haoyu wrote them on the basis of a poem by Wei. If you have any further information about the song or the artists, please share it in the comment section below or email us.

- Wei’s family was formally notified of his arrest in early August on the charge of “picking quarrels,” and, at the time of this writing, the status of his colleagues Yang and Ke are still unknown: “Wei Zhili formally arrested, Yang and Ke status unknown, right to see lawyer denied”, 10 August 2019, China Labor Crackdown Concern Group, <https://laoquan18.github.io/formalarrest/>

- Source: 为尘肺工人而rap:这一次,嘻哈真正回归了它的地下属性, <http://tootopia.me/article/10572>