This is Part 4 in our serialized translation of the 2024 year-in-review “Keeping Each Other Afloat in a Difficult World: Taking Stock of Labor Struggles in 2024” produced by an anonymous group of netizens. Part 1 of our translation can be found here, Part 2 here, Part 3 here, and the Chinese original can be found here.

While the rights of workers in specific workplaces have certainly been impacted by the broader economic climate and by prevailing conditions across industry, the issue ultimately comes down to the power relationship that the firm establishes between itself and its employees as the designer and enforcer of micro-level management systems. Alongside this year’s waves of mass layoffs and salary cuts, overtime and unpaid overtime for the remaining employees have also grown more severe, while incidents of suicide and death from overwork have been occurring more frequently. Under the banner of “cost reduction and efficiency improvement,” some companies have chosen to alleviate operational difficulties at the expense of employee welfare even though there is not an obvious relation between the two. The deepening of contradictions between labor and capital cannot entirely be captured in the phrase “economic winter” on its own. At root, they stem from ordinary workers lacking democracy and having no ability to genuinely participate in corporate management.

Notorious practices such as the “996” work system, long criticized in public discourse, also saw no improvement this year.[1] In January, the well-known short video platform Kuaishou was exposed for implementing an “11.5-hour work system,” requiring employees to work at least 11.5 hours after clocking in before they could clock out. In May, Qu Jing, head of Baidu’s public relations department, sparked public outrage with statements on Douyin such as “when employees threaten to resign over a break-up, I immediately approve it,” and noting that employees are expected to keep their phones on 24 hours a day. This led to widespread disgust with Baidu’s corporate culture and a temporary drop in its stock price, ultimately ending with Qu Jing leaving the company. In June, CATL exhorted its employees to “strive for 100 days” under a “896” work system [8.am. to 9 p.m. six days a week]. The issue of excessive overtime in the automotive industry also drew attention. According to explosive allegations made by industry insiders, Tesla factories have long operated on a 12-hour system, reducing pay for anyone working shorter hours, while NIO employees reported working 500 hours of overtime in six months without receiving any overtime pay. Digital work saw similar trends. On June 27th, a female livestream host suddenly fainted during a broadcast on a channel for the brand Chicecream, drawing public concern. Follow-up reports stated that she had already been feeling unwell due to her menstrual cycle and was working while sick. The company later stated that the host had sought medical attention. This incident reflects the severe conditions of overwork still prevalent among livestream hosts.

NIO calls on its employees to “strive for 100 days”

Service industries such as food delivery, courier services, ride-hailing, cleaning, and security—which serve a strategic function in absorbing the unemployed population—have also grown overcrowded and increasingly competitive, with work-related deaths occurring repeatedly. In September, a 55-year-old delivery rider in Hangzhou known for his extreme work ethic died suddenly while resting on his electric bike. In August, a 33-year-old security guard in Guangdong died suddenly in the restroom during a night shift. In another incident in Shanghai, a janitorial worker known as Auntie Li suddenly fainted while in line to clock out after work and died despite efforts to resuscitate her at the hospital. Before the incident, she had spent 10 continuous days working overtime, with daily shifts exceeding 12 hours. Meanwhile, the company failed to send her to the hospital promptly after she fainted. After her death, her family pressed the Shanghai Jing’an District Court to hear the case in April.

Service industries such as food delivery, courier services, ride-hailing, cleaning, and security—which serve a strategic function in absorbing the unemployed population—have also grown overcrowded and increasingly competitive, seeing repeated work-related deaths. In September, a 55-year-old delivery rider in Hangzhou known for his extreme work ethic died suddenly while resting on his electric bike. In August, a 33-year-old security guard in Guangdong died suddenly in the restroom during a night shift. In another incident in Shanghai, a janitorial worker known as Auntie Li fainted while in line to clock out after work and died despite efforts to resuscitate her at the hospital. Before the incident, she had spent 10 continuous days working overtime, with daily shifts exceeding 12 hours. The company had failed to send her to the hospital promptly enough after she fainted. In the wake of her death, her family pressed the Shanghai Jing’an District Court to hear the case in April.

Sectors such as education and healthcare also see widespread overtime, which is easily overlooked due to the nature of the work. On March 14th, according to media reports, a teacher at a private school in Fengang Town, Dongguan was found dead in the school’s dormitory. A police source informed reporters that the preliminary cause of death was determined to be “sudden death.” On April 2nd, a young faculty member at Nanjing Forestry University, Dr. Song Kai, chose to end his life after failing his first employment evaluation, resulting in a demotion and salary reduction and being required to return part of his relocation allowance and housing subsidy. Meanwhile, a survey from this year showed that the average weekly working hours for primary and secondary school teachers in China is 52.36 hours, exceeding the legal working hours by 12.36 hours per week, with half of surveyed teachers reporting that they suffered from anxiety.

In healthcare, excessive working hours have caused multiple work-related deaths. For example, on January 12th, at the age of 46, Chief Physician of the Anesthesiology Department at Nantong University Affiliated Hospital, died from a sudden illness. Relatives stated that he had been continuously working overtime while recovering from a cold, which triggered a serious heart attack. It goes without saying that patterns of high-intensity work over extended periods cause severe harm to employees’ physical and mental health. Chronic fatigue and stress have not only led to many irreparable tragedies but also caused a number of social conflicts.

It is important to clarify that, even in the context of the current economic downturn, a significant number of enterprises still have sufficient latitude in their decision-making to pass policies that would improve the pay and working conditions of their employees. As early as last year, some domestic firms had drawn inspiration from practices overseas and started experimenting with a four-day workweek. This year, several more companies have continued the trend, courageously taking the first small steps toward reform and delivering tangible benefits to their employees.

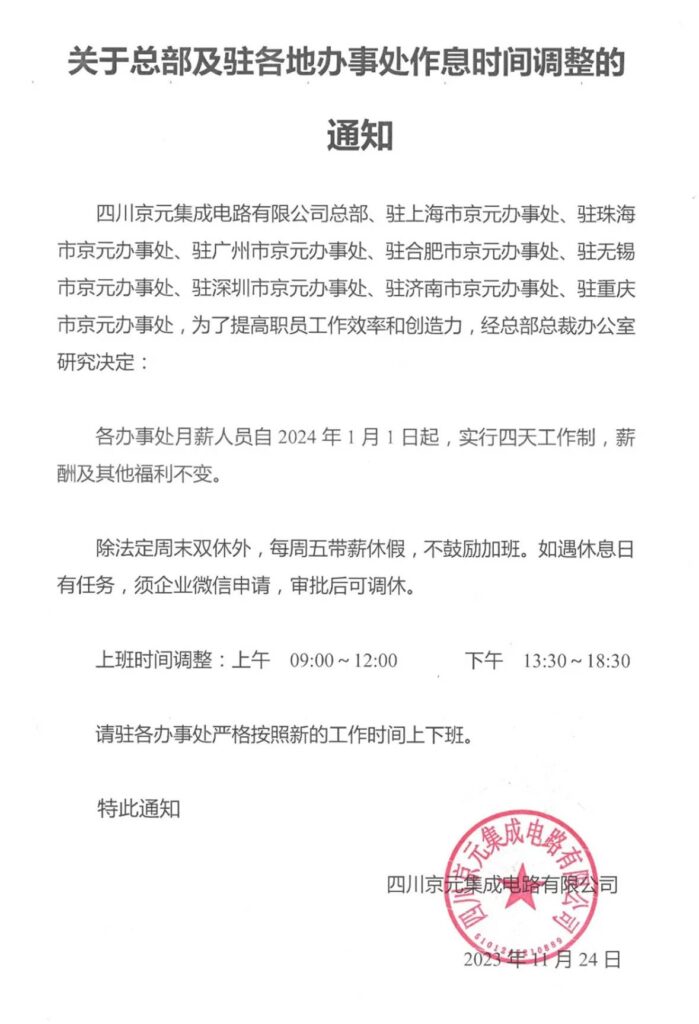

At the beginning of the year, Sichuan Jingyuan Integrated Circuit Co. announced that, starting on the 1st of January 2025, it would implement a four-day workweek for its salaried employees across all departments with no changes to total compensation or benefits. Employees would enjoy paid Fridays off, overtime would be discouraged, and standard working hours would be modified to shifts of 9:00-12:00 in the morning and 1:30-6:30 in the afternoon. If work-related tasks arise on the weekend, employees can apply for additional time off in compensation through the company’s WeChat—requests that are subject to the approval of management. In November, a design firm in Changsha also announced that it would implement a four-day workweek system beginning on December 2nd, 2024, with Wednesdays off and working hours from 10:00-4:30. Companies experimenting with the new four-day workweek mostly hope to enhance employee efficiency and creativity through optimized systems that strike a better balance between work and home. These initiatives reflect new corporate thinking with regard to work methods and employees’ rights.

The notice sent out by Sichuan Jingyuan Integrated Circuit announcing its new four-day workweek policy.

Aside from overtime policies, issues such as privacy violations and abuse of non-compete agreements by major tech firms have also drawn widespread public attention.

E-commerce firm JD.com has frequently made headlines for its strict attendance checks, workforce “optimization” efforts, and measures to address the bureaucratization that attends enterprise growth (so-called “large company disease”). In May of 2024, founder and chair Richard Liu’s blunt statement during a video conference with senior management that “those who don’t work hard aren’t my brothers” sparked widespread ridicule. That same month, reports circulated online indicating that the company was forcing employees to allow management to inspect their private chat histories on their own personal phones and terminating anyone who refused to comply. Some employees who commented on the phenomenon in the company’s internal forum were called into HR and pressured to submit their resignations after having just completed their probationary period. The incident triggered intense public debate about corporate overreach and employee privacy protections, with the mainstream opinion being that companies must place clear boundaries on their authority and respect employee privacy. Meanwhile, an entertaining public saga documenting the “Adventures of a British White Guy in a Chinese Tech Giant,” can perhaps be understood as a tongue-in-cheek commentary on the tech industry’s overtime culture in 2024: when it comes to corporate exploitation, everyone truly is equal.[2]

Another widely criticized practice among major tech firms in 2024 has been their abusive use of non-compete agreements in employment contracts. In February, several former employees exposed Pinduoduo for misusing these agreements. Facing intense workloads during their time at the company, they were then frequently subject to covert surveillance and tracking after they left. Many were subsequently sued by their former employer for exorbitant amounts—ranging from hundreds of thousands to over a million yuan—for having allegedly violated their non-compete agreements. One whistleblower even claimed that there was a “revolving door” between Pinduoduo and local government officials in Shanghai.

Meanwhile, a former ByteDance employee made a post titled “I worked myself to death for ByteDance for two years only to get maliciously forced out and told to return all my wages,” sparking heated discussion. In the post, the author claimed to have worked for the company for two years before being targeted due to conflicts with their superiors, after which they were then forced to sign a non-compete agreement in order to obtain their resignation certificate. After the author signed on with another firm, ByteDance then sued them for 600,000 yuan.

Non-compete clauses in employment contracts were originally meant to apply only to a small handful of workers with access to technical or commercial secrets. But these clauses are now standard in all sorts of contracts, effectively becoming a tool for companies to control employees’ mobility. Many lead firms in various industries never even intend to fulfill their end of the contract, failing to give their employees their contractually-mandated compensation, and yet these same companies demand that exorbitant penalties be paid by any employees deemed to have breached the non-compete clause. This amounts to nothing less than “killing the donkey once it’s done grinding.” Lawsuits and rights defense efforts related to these cases are ongoing.

One company was subject to particularly close scrutiny this year: the retail firm Pangdonglai. Against a backdrop of intensified conflicts between capital and labor, with no end in sight, it’s hardly a surprise that Pangdonglai’s “unique” corporate policies and culture have stirred up wave after wave of discussion.

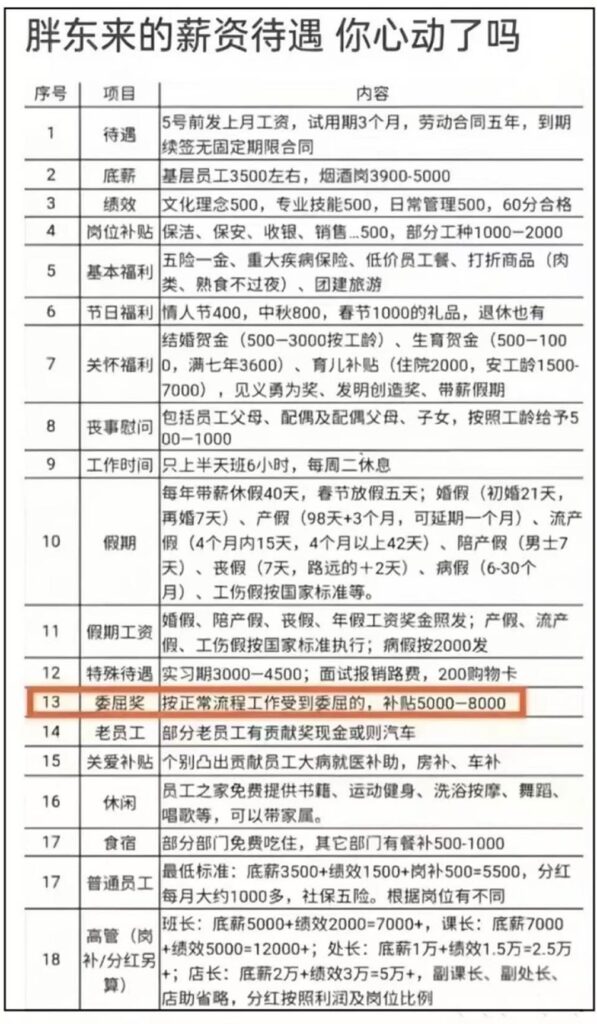

A Henan-based supermarket chain praised by local consumers, Pangdonglai has also earned widespread acclaim from its workers for its exceptional benefits, such as wages calculated based on local housing prices, the allocation of 80% of profits to improve the living standards of staff, clear paths for career advancement. Employees also enjoy a number of material benefits, including over 30 days of paid leave, strict eight-hour days with no overtime, mandatory approval of leave requests, and well-equipped rest areas. Some commentators have even commended the company as a “socialist enterprise” for its employee care philosophy, which is centered on principles of “happy work,” “freedom and love,” and “a fulfilling life.”

Pangdonglai salary and benefits as reported online

Whether or not the praise received is excessive, Pangdonglai’s institutional philosophy of prioritizing social responsibility over profit maximization stands in stark contrast to mainstream Chinese companies which, since the reform and opening period, have long championed expansion, competition on the market, and extreme forms of worker exploitation, thereby generating substantial negative externalities. Regardless of the exact viewpoint, the debate about whether Pangdonglai embodies “socialist” principles or represents a form of “revolution,” as counterposed to “reform,” serves as a recognition of this fundamental difference. Many observers argue that Pangdonglai represents a new corporate value system that incorporates Nordic-style concepts of “social democracy” and the “welfare state,” offering a potential future direction for China’s economic governance. This approach not only aligns with the globally popular ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) movement but also offers a viable solution to the dilemma of “involution” and presents a pathway toward “common prosperity.”

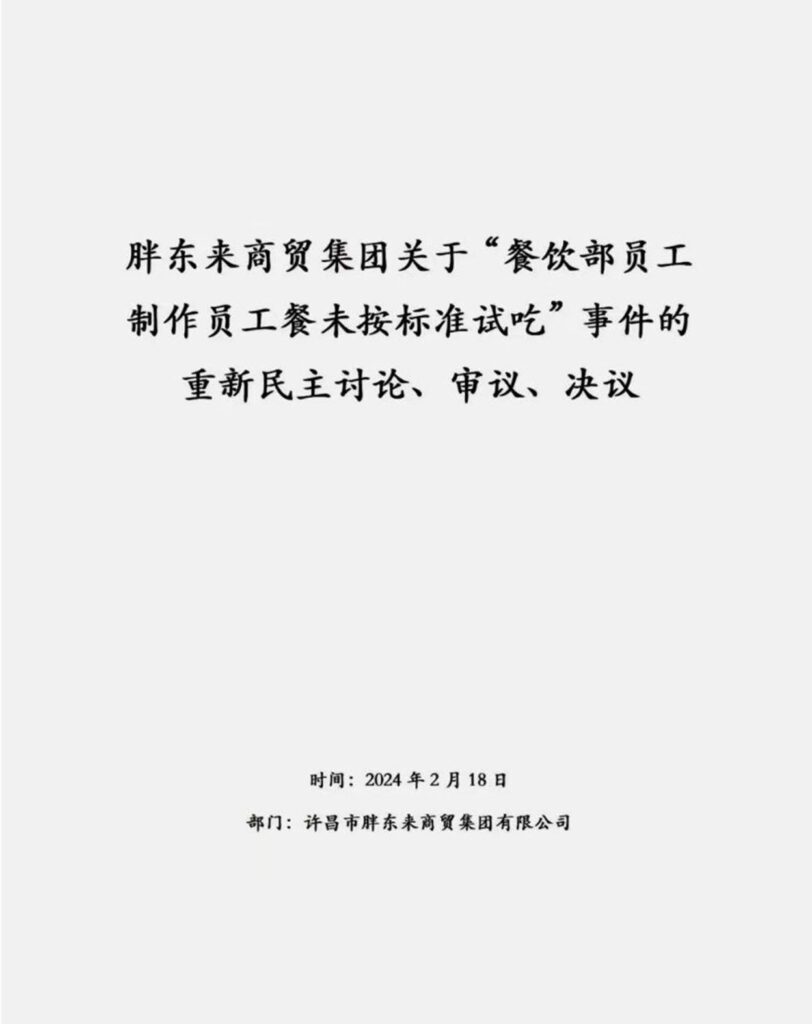

To a certain extent, Pangdonglai has indeed incorporated the concept of “economic democracy”—understood as the participation of workers and other stakeholders in corporate governance—into its management practices. For example, when an employee was found to have sampled noodles in a store without authorization in February of 2024, the company initially decided to dismiss the worker. However, this triggered public backlash online and, in response, the company made use of a democratic process to revise its decision and instead reassigned the employee. In a final report totaling 13 pages, the company documented in detail how the decision was made via a “democratic deliberation panel” that involved the participation, discussion, and votes of the employee in question as well as representatives from multiple levels of management. A process like this remains an extremely rare case in corporate governance in post-reform era China.

The title page of Pangdonglai’s report on the “food tasting incident”

However, in November of 2024, Pangdonglai triggered a significant backlash when it announced that employees would lose all their benefits if they demanded bride prices when getting married. While some netizens agreed that exorbitant bride prices are an undesirable social practice, many others criticized the company for overstepping boundaries by attempting to regulate the private lives of its employees through punitive measures. Pangdonglai later clarified that the measure was merely a proposal and not yet an active policy. Following this, controversies then arose over strict management practices exposed by former employees, such as a “home visit system” and a requirement that cleaners create PowerPoint presentations as a part of meticulous performance evaluations.

It is indeed possible to observe in Pangdonglai’s corporate management practices an innovative approach to pushing social transformation forward through corporate governance. And yet it is also possible to detect a trace of a paternalistic moral economy—a tradition that extends from the first thirty years of the PRC’s history back to even older roots in agrarian culture. To borrow a formulation from E.P. Thompson, these practices reflect “a consistent traditional view of social norms and obligations, of the proper economic functions of several parties within the community…”[3] Thus, two opposing perspectives consistently appear in the debates on the Pangdonglai policies: advocates of the free market view the company as a threatening representation of inefficient labor management in violation of modern market principles; while supporters of labor rights hail it as a genuinely progressive model—if not a lonely piece of socialist driftwood afloat in the ocean of capitalism, then at least a reformist vision for achieving “labor-capital harmony” within the existing institutional framework.

But it must also be emphasized that the discussion around Pangdonglai has not been grounded in any in-depth research or field studies. The company has not only become a projection of our idealized images of economic organization but also a focal point in the ongoing public debate over different approaches to economic governance. Discussion of Pangdonglai is certain to continue for some time and, as the saying goes, “why not let the horse run a while longer.”

Finally, it is also worth noting that the newly revised Company Law, amended in December of 2023, has incorporated provisions that strengthen corporate democratic management and protect the legitimate rights and interests of employees. Effective July 1st, 2024, the law not only regulates employee stock ownership plans and equity incentives but also introduces, for the first time, various provisions on the democratic management of companies. For all companies above a certain size and regardless of ownership structure, it mandates employee representation on boards of directors, supervisory boards, and audit committees, it reinforces the status and rights of company unions, and it establishes representative assemblies for employees as a fundamental form of democratic management within the firm. For workers, this represents a modest step forward. And yet significant challenges remain under the current system. For example, how might these institutional changes be prevented from becoming mere formalities, as has happened to similar laws in the past? How to ensure that employees genuinely gain the experience, capability, and right to participate in management? And, of course, will the policies avoid discouraging grassroots initiatives organized by the workers themselves?

[1] Translators: The “996” work system refers to a schedule in which workers, mostly in the tech sector and other white collar occupations, work 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., 6 days a week.

[2] Translators: This refers to the story of Jack Forsdike, a British worker subject to extreme overtime at NetEase, documented on his Xiaohongshu account. The case is documented here: Dominic Morgan, “Chena’s Gen Z Finds an Unlikely New Hero: A Sad, Tired Brit”, Sixth Tone, 05 September 2024. <https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1015826>

[3] E.P. Thompson, “The Moral Economy of the English Crowd in the Eighteenth Century”, Past & Present, No. 50, February 1971. p. 79