This is Part 3 in our serialized translation of the 2024 year-in-review “Keeping Each Other Afloat in a Difficult World: Taking Stock of Labor Struggles in 2024” produced by an anonymous group of netizens. Part 1 of our translation can be found here, Part 2 here, and the Chinese original can be found here.

According to a survey by the All-China Federation of Trade Unions, the number of workers in “new forms of employment” surpassed 84 million in 2024 to compose 21% of the total workforce. The gig economy—which serves as an employment reservoir for rural youth migrating to the cities, for recent graduates, and for those thrown into unemployment—has grown increasingly saturated, intensifying competition among platform-based gig workers. The influx has led to declining pay rates per task and stricter oversight of platform-based gig workers. As income grows more uncertain, accidents and violent incidents occur more frequently.

According to official data from Meituan, among the 7.45 million delivery riders who earned income from orders on the platform in 2023, nearly half worked fewer than 30 days, indicating that a significant proportion were using these jobs for part-time or transitional employment. The myth of “earning over 10,000 in a month” has already become an illusion. In reality, pay rates are falling lower and lower. One delivery rider in Shenzhen interviewed by Sanlian Lifeweek stated that he had to ride over 5,000 km per month, complete between 1,000 and 2,000 orders, and work at least 13 hours a day to earn over 10,000 in a single month. Although the 2023 Blue-collar Employment Survey Report noted that the average monthly income of delivery riders in 2023 was 6,803 yuan (higher than the blue-collar average of 6,043 yuan) and that delivery riders, postpartum caregivers, and truck drivers ranked among the top blue-collar earners, the Gig Economy Research Center’s annual survey revealed that, in Guangdong, half of all surveyed delivery riders had earned less than 4,000 yuan per month on average over the previous three months, with fewer than 20% earning more than 6,000 yuan. Among those who did, 69% worked 8 to 12 hours a day.

In recent years, the per-unit pay of food delivery riders has consistently fallen. According to one delivery rider interviewed in Caixin, when they first started the job in 2019, they earned 5-6 yuan per order, with orders over three kilometers paying up to 10 yuan. But now the fee for orders over three kilometers has been halved to 4.5 yuan, while orders within three kilometers have dropped to between 3.8 and 4.2 yuan. For “free-run” riders, rates have dropped below 3 yuan and high temperature subsidies have also been eliminated.[1] Since Meituan’s delivery riders are paid using a tiered system based on the number of orders completed, riders who make fewer deliveries receive lower per-order payments. At one station in Hangzhou, riders completing fewer than 700 orders per month earn 4.45 yuan per order while those completing over 1,300 orders earn 5.05 yuan per order. In January 2024, delivery riders in Yantai, Shandong, reported that they had had their wages withheld by a Meituan franchise station since October 2023. Shortly after raising the issue, their Meituan rider accounts were suspended. However, a Meituan channel manager claimed to be unaware of the situation.

Numerous factors have increased the risks associated with platform-based gig work, leading to a growing number of accidents, including sudden deaths. As global warming intensifies, extreme summer heatwaves and heavy rainstorms have become more frequent. On July 10th, a 23-year-old delivery rider collapsed on the streets of Shenzhen and was taken to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with heatstroke and later died despite treatment. Since August, temperatures exceeding 40°C (104°F) baked regions across the country, yet delivery riders, including those working as “special delivery” (i.e. high regimentation, high pay) riders for Meituan in a first-tier city, reported that they never received high-temperature subsidies. According to the “Measures for the Administration of Heatstroke Prevention and Cooling” workers subject to work in high temperatures are legally entitled to job-specific allowances. Employers must provide high-temperature subsidies to workers performing outdoor tasks in temperatures above 35°C or in workplaces where the temperature cannot be effectively reduced below 33°C, and these subsidies must be added to their total pay. However, food delivery platforms often use high-temperature subsidies to fund publicity activities (such as setting up “cooling stations”) rather than offering fixed allowances.

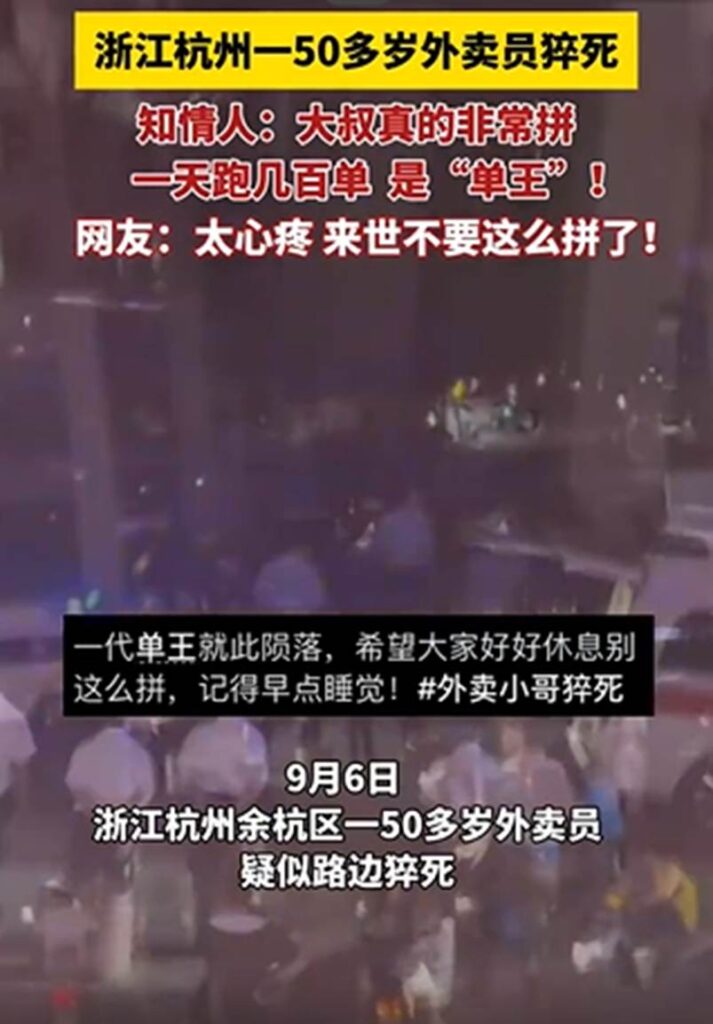

On September 6th, a video showing a delivery rider in Yuhang District, Hangzhou dying suddenly while resting on his electric scooter went viral. He was reportedly a top-performing rider in the area, often working until 3 a.m. and getting only three to four hours of sleep a day, using brief moments between orders to rest on his scooter. According to knowledgeable sources, he came from a financially struggling family and pushed himself to work day and night to increase his income.

On September 23rd, a warehouse employee working for a third-party platform operating on behalf of Dingdong Grocery was found dead in his rented room in Beijing. The 42-year-old worker often worked 12-hour night shifts before his death and had been working overnight for several consecutive days during the Mid-Autumn Festival. Prior to his death, he had reported feeling unwell and requested leave from his store manager on September 18th, saying that he was bleeding from the eyes and couldn’t see clearly. Soon after, no one was able to contact him. Since his contract was not directly with Dingdong Grocery but instead via a “Freelancer Service Agreement” signed with the third-party labor brokerage firm Yunqiandou, his death could not officially be classified as a work-related injury. As a result, his family reportedly only received “tens of thousands of yuan” in sympathy compensation.

Platform-based gig workers also faced strict supervision from platforms, regulatory agencies, and even the property management offices of housing developments. In the express delivery sector, the newly revised “Measures for the Administration of the Express Delivery Market” went into effect on March 1st of 2024. The new regulations set heavy fines ranging from 10,000 to 30,000 yuan for delivering packages to smart lockers or delivery service stations without the prior consent of the recipient. Just two days after learning about the stipulations, one courier resigned, stating that they would make it harder to resolve disputes over lost packages and that the number of packages requiring delivery to the doorstep would likely surge. Another courier reported that, after making a delivery, riders are now required to “call the recipient to confirm and let the phone ring for at least 10 seconds.” Some couriers have said that the new regulations would reduce their daily delivery volume from 400-500 parcels to around 100-130.

The imposition of fines has also long been a norm among the “big four” last-mile logistics firms STO Express, ZTO Express, YTO Express, and Yunda Express. One courier reported receiving more than a dozen complaint calls in a single week and total fines of up to 2,000 yuan. According to the “2021 China Courier Rights Protection Survey,” nearly 60% of couriers were fined over 200 yuan per month. Couriers feel that the new regulations are just the last straw. Under a system in which delivery riders are made to bear all the responsibility and all the costs and fines are used as an administrative tool, there isn’t even a way to withdraw a complaint on the consumer’s end. If a customer clicks “package not delivered” while checking the status of their delivery, the system automatically issues a fine of 50 to 100 yuan for the rider and this fine cannot be cancelled. Attempting to cancel the ticket by filing a new one only results in an additional complaint.

Additionally, gaining access to residential compounds and commercial buildings to deliver orders continues to pose difficulties for food delivery riders. Security guards, who face fines for allowing access, are pitted against riders, who face penalties for late deliveries and customer complaints. The system thereby places the two in permanent antagonism. In December of 2023, a tragic incident of mutual violence among the lower class broke out in Qingdao when a 32-year-old delivery rider got into a dispute with a 54-year-old residential security guard, which ultimately resulted in the guard’s death. In a similar situation, a delivery rider in Beijing named Feng Wenxue chose to sue Changyiyuan, the property management firm associated with a building he frequently delivered to, citing the Constitution in defense of his rights. Feng alleged that, over his four years as a delivery rider, he had faced issues such security guards impolitely searching him and denying him access to the building, restrooms in the building being under prolonged repair, uneven road services causing falls, and the building escalators being out of service. His responses to these issues ranged from arguing, complaining to the 12345 government hotline, calling the police, and finally filing the lawsuit. He also attempted to organize a union for gig delivery riders. While many of these issues were eventually resolved, the court ruled in June of 2024, rejecting all of his claims regarding delivery riders’ rights to enter residential complexes and stating that “residents of the complex have property rights over the shared public areas and roads, and delivery riders do not have any legal entitlement to these spaces.”

On August 12th, an image of a food delivery rider kneeling on the side of the road circulated widely online. According to an official statement, the rider, surnamed Wang, was stopped by security guards after he accidentally bent a railing while making a delivery at the Xixi Century Center in Xihu District, Hangzhou. When stopped, Wang knelt down in desperation, concerned that the stop would prevent him from delivering his other orders on time. The incident set off a wave of support from other delivery riders, who gathered at the scene to demand rectification from the property management. Multiple videos showed large crowds of delivery workers assembling at Lucheng Xixi Century Square shouting and demanding an “apology.”

Some of the new regulatory measures appear to exert control over platform algorithms and protect rider safety but have in reality failed to alleviate the difficulties faced by riders. On July 9th, a regulation issued in Guangzhou stating that “food delivery riders who violate traffic laws more than three times in a given week will be banned from delivery work” sparked widespread discussion. On September 27th, the Guangzhou Municipal Market Supervision Bureau put forward new regulations further strengthening supervision over riders and delivery firms, dubbed the “strictest new rules” within the industry. The new rules clearly stipulate that riders will face a one-day suspension after their third traffic violation and may even have their vehicle impounded. Four or more violations will result in longer suspensions and accumulating ten violations in the space of three months will result in being placed on a blacklist that bans them from the entire industry. One of the motives of the policy in Guangzhou is to manage the surge in e-bikes and set standards for their use, but it overlooks the interests of the delivery riders themselves. Some riders have been forthright in explaining their conundrum: “If we don’t speed, we’ll be late.”

However, the new rules not only place restrictions on the riders but also require that the companies that own the platforms set their time limits and routes in accord with the assumption that the deliveries can be completed in compliance with the maximum speed limit of 25 km per hour. The rules also explicitly state that the “strictest algorithms” should not be used in evaluating riders and, instead, that platforms should employ moderately lenient algorithmic parameters to reasonably determine evaluation metrics such as order volume, the rate of orders delivered on time, and the rate at which workers are signed into the platform, and appropriately relax delivery time limits in accord with actual conditions. On December 5th, Guangzhou’s new e-bike regulations then imposed an even more strict speed limit of 15 km per hour. The Guangzhou traffic police also stated that they would work alongside market supervision departments to meet with the platform companies, urging them to relax the delivery time limits. However, the latest reports indicate that, on December 30th, the first day that the new rules went into effect, delivery drivers had not noted any changes in the time limits listed on the platforms.

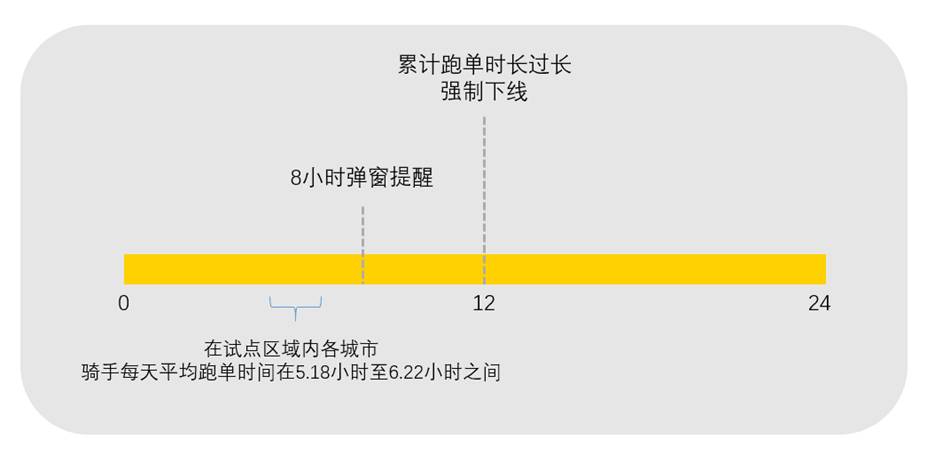

On August 9th, the Shijiazhuang Municipal Bureau of Human Resources and Social Security in Hebei Province issued the “Shijiazhuang City Guidelines on Managing Labor Practices in New Forms of Employment (Trial)”, which proposed that food delivery platforms should impose a 20 minute pause on orders for riders after they have been delivering continuously for more than 4 hours to prevent potential accidents caused by prolonged work. On December 17th, both Meituan and Ele.me announced that they had already begun piloting and optimizing mechanisms to prevent fatigue in certain cities. When the app detects that a rider has been working for too long, it will initially send a reminder to the rider to rest. If the rider ignores the reminder, the app will then force them to sign out and take a break. In response, delivery riders took to social media, explaining:

the ones who work long hours are usually the ones facing the most severe financial hardship. If the core problem of low pay per order isn’t addressed, limiting working hours will only push workers to try to complete more orders in less time, leading to greater pressure to work faster and more unsafe practices, ultimately fueling even harsher competition.

Moreover, when regulations are unilaterally imposed by the government or the platforms without involving riders in the decision-making process, the result is simply wishful thinking. On December 27th, Meituan announced plans to abolish the penalty system for late deliveries by 2025 and introduce positive incentives such as training and point-based systems. This is seen as a more sincere approach compared to anti-fatigue mechanisms that force riders to log off. But the implementation remains to be seen.

Compared to the food delivery, courier services, and logistics sectors, drivers for ride-hailing platforms were once considered to occupy one of the more stable forms of platform-based gig work. However, since the beginning of 2024, the price of new energy vehicles (NEVs) has fallen and fares have seen a continuous decline, such that fares on certain platforms are now as low as .01 yuan per km. even though the operating cost for ride-hailing drivers fully complying with regulations is as high as 1.2 yuan per km.

According to a report compiled by the National Business Daily, multiple regions issued risk warnings for the ride-hailing industry in July stating that transport capacity has already met or even exceeds demand, issuing a public warning against new entrants into the industry. According to the latest data from Guangzhou’s Municipal Transportation Bureau, the local daily average revenue for drivers has dropped from 343.34 yuan to 311.63 yuan. This means that even if some drivers work an entire month without a single day off, before deducting vehicle costs, their total monthly income will not be more than 10,000 yuan. As early as February, media reports indicated that, if passengers place orders through third-party platforms rather than the ride-hailing companies’ own platforms, drivers’ take-home income would be reduced by roughly 20% due to both the original platform and the third-party platform taking a commission.

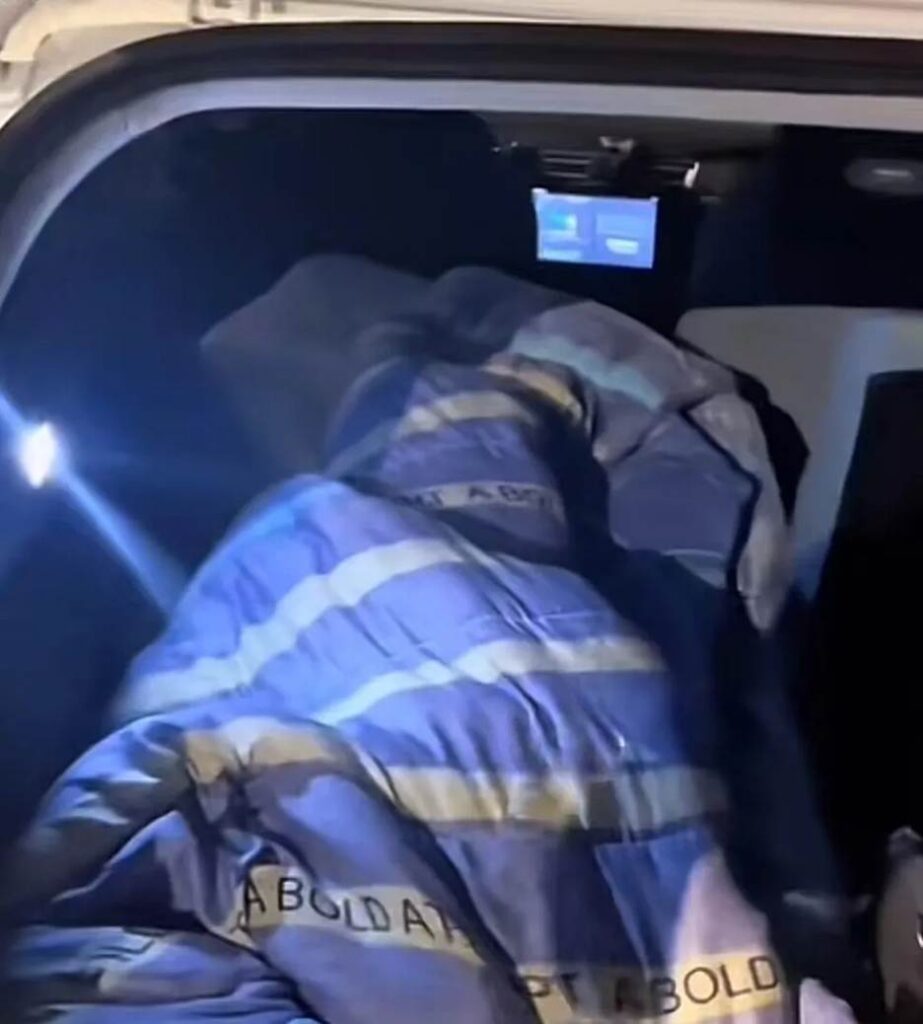

The fall in fares has resulted in a continuous decline in drivers’ desire to comply with regulations. As a result, the share of transportation capacity in compliance with regulations has fallen. Among both new and experienced drivers, more and more are now turning to unlicensed rideshare services. Since ridesharing regulations permit drivers to consult with passengers over highway tolls or even operate offline, some fear that this indicates the return of “black taxis” to the market. Under these operational pressures, some men who drive full time have resorted to eating, drinking, and sleeping in their cars to save on living costs like rent, especially in megacities like Beijing and Shanghai. Only using paid bathhouses to shower, this practice has inevitably led to vehicles with unpleasant odors. As a result, the topic “getting a smelly car is becoming more common” now frequently trends on social media. Many passengers have also noted that the chances of getting a smelly car are higher when booking discounted rides. In December, Didi Chuxing responded by launching a special campaign to address the issue of “smelly cars,” introducing a feature that allows customers to blacklist vehicles with unpleasant odors and announcing that drivers who have extremely negative ratings for interior air quality will face disciplinary measures such as suspension and mandatory trainings. However, placing the blame entirely on the drivers only increases the pressure that they face. Without any improvement in the dispatch algorithms used by the platforms or any restructuring of the revenue-sharing model between platforms, third-parties, and drivers, such measures are unlikely to provide any real improvements. Similar forms of governance are also visible across other platforms: Huaxiaozhu has tightened controls on drivers’ abilities to cancel orders, while Shouqi Yueche has strengthened oversight of drivers’ completion rates and complaint records, and introduced a penalty system.

Meanwhile, women ride-hailing drivers have also garnered more attention. In March of 2024, ride-hailing platform T3released its “2024 Annual Data Report on Female Driver Employment” which showed that of 70,000 women had joined the platform as of February 2024, compared to just 21,000 in 2022. Women drivers are mainly concentrated in both established and new first-tier cities such as Shanghai and Nanjing. Individuals born in the 1970s and 1980s account for more than 80% of women in the field, and more than 60% of them work more than 8 hours every day. Compared to male drivers, female drivers exhibit fewer abnormal behaviors such as distracted driving, fatigued driving, and phone use while driving, on average, indicating that they are more focused and cautious behind the wheel. The debate on differences between male and female drivers has again placed the intersection of gender and labor rights into the public spotlight. We should recognize that, without addressing platform exploitation, attributing female drivers’ better performance in certain areas to their gender risks reinforcing gender norms and imposing more stringent evaluation pressure on male drivers (re: abuse, mistreatment, and manipulation). Ultimately, the demands of both male and female drivers may fail to garner an adequate response from the platforms.

In July of 2024, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (MOHRSS), working alongside other departments, concluded its two-year pilot program offering occupational injury protection for workers in “new forms of employment,” and official media outlets have reported that the program will continue to expand. Unlike standard occupational injury insurance, the new occupational injury protection does not require a formal employment relationship or use gross wages as the basis for its fee calculations. Instead, platform companies calculate contributions on a per-order basis and report and pay out premiums based on the monthly volume of orders. Taking the food delivery sector as an example, the new system is capable of covering every individual and every order. Even if a rider only completes a single order, they can still apply for benefits if they are injured on the job.

Reports indicate that, although the pilot program achieved positive results, extending coverage to 8.017 million people by the end of March 2024, it currently only applies to the ride-hailing, food delivery, instant delivery, and last mile freight industries across seven provinces and centrally-administered cities—Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Guangdong, Hainan, Chongqing, and Sichuan—and applies to work under seven platforms, including Meituan, leaving coverage relatively limited. On August 2nd, a spokesperson for the MOHRSS stated that the program would now be gradually extended. But many compensation cases for workers in “new forms of employment” also involve third-party liabilities, which the current pilot program does not yet cover.

The pilot program has not received any attention in media coverage of deaths and injuries among food delivery riders. For example, the family of the rider who died of heatstroke mentioned above did not receive any compensation from the Human Resources Department. Similarly, news about the deaths of a Hangzhou delivery rider and an employee of Dingdong in Beijing, also failed to mention any of the relief methods offered under the new program.

Beyond delivery riders and ride-hailing drivers, the conditions of other groups of gig workers have received relatively less attention from mainstream discourse. A report on the labor conditions in the recently booming short drama industry mentioned that high-intensity work of up to 20 hours a day has become the norm for employees in various occupations within the sector, where low-level not only face low wages and frequent delays in payment but also lack formal contracts for the most part, meaning that their working conditions are not protected under the law whatsoever. Actors revealed that, within the past year, five people had died due to high-intensity work, being treated as completely “expendable.” Wang Ma, once hailed as the “voice of the workers” for her role in the short drama series posted on Wang’s affiliated Seven Gorillas channel also faced backlash after netizens discovered that she mistreated her own subordinates by posting recruitment ads for jobs requiring alternating five- and six-day workweeks. In reality, however, this practice was not unique to Wang’s company. It is instead very common among influencer-related jobs, which offer low pay, require long working hours, and demand that a single person juggle multiple roles, all without being formally considered employees. In addition, the terms of the contracts often include unfair clauses such as requiring that employees pay huge penalties for breaching the contract by quitting.

[1] “Free-run” is one of several different labor deployment models used by Meituan. Compared to the others, it is less regimented and receives less oversight, but also sees poor pay per task. “Free-run” can be contrasted to higher-regimentation and higher-pay forms labor deployment such as “Special Delivery” and “Happy-run.”