This is Part 2 in our serialized translation of the 2024 year-in-review “Keeping Each Other Afloat in a Difficult World: Taking Stock of Labor Struggles in 2024” produced by an anonymous group of netizens. Part 1 of our translation can be found here, and the Chinese original can be found here.

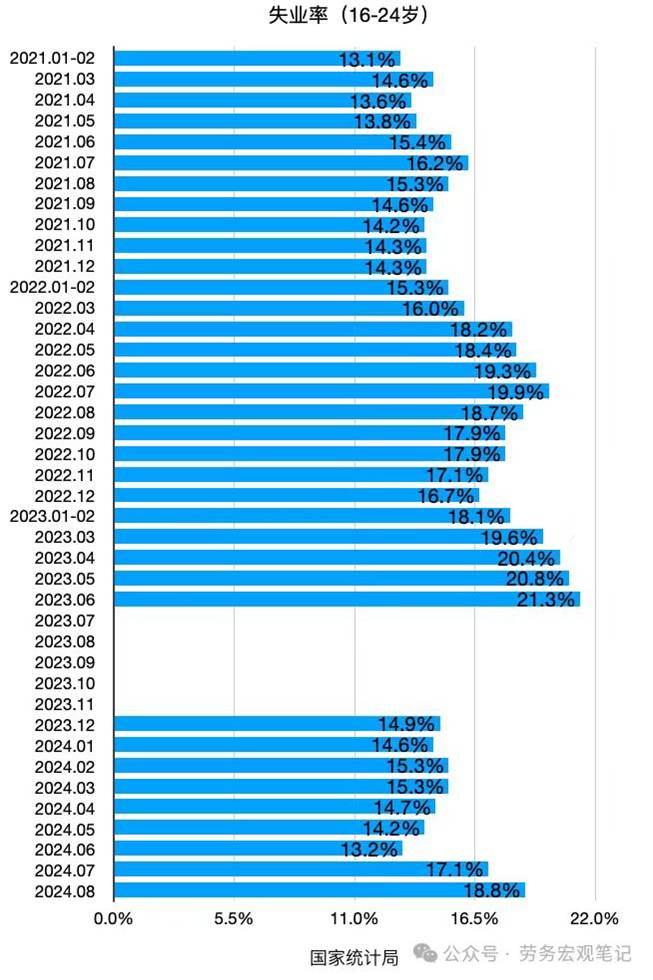

In August 2023, in the midst of record high rates of youth unemployment, the National Bureau of Statistics temporarily suspended the publication data related to the topic. Despite subsequent statistical adjustments after the data series resumed, youth unemployment continued to soar beyond June 2024 and reached 17.1% in July. Moreover, in contrast with the usual trend seen in previous years, in which the rate typically peaked and then declined during the summer, it instead rose to 18.8% in August, surpassing the figure for most months recorded under the previous statistical framework. Although the rate then declined in September and October, it remained at an elevated level in excess of 17%.

Due to changes in statistical methodology, the youth unemployment rate data in 2024 cannot be directly compared with previous years. However, according to Zhaopin’s “2024 College Graduates Employment Survey,” the rate of job offers for those with a master’s or doctorate was 44.4% as of mid-April, while the rate for those with a bachelor’s degree was 45.4%, both lower than 2023. In terms of plans following graduation, the proportion of new graduates opting for delayed employment or freelance work has also increased compared to the previous year. This indicates that youth employment challenges persisted into 2024 amid the continued economic downturn and may have even been more severe than in 2023.

In the midst of the economic crisis and widespread downturn across industries, the number of high-quality job openings has also declined, driving young workers to seek out more stable jobs in the public sector and in government-adjacent institutions (i.e., positions within “the establishment”).[1] For example, the College Graduates Employment Survey showed a continual increase in the share of college graduates hoping to enter state-owned enterprises between 2020 to 2024, when the figure reached 47.7%. Similarly, the number of applicants for the national civil service exam reached 3.41 million in 2024, a 12% increase compared to the previous year, even while the number of applicants for the 2025 postgraduate entrance exam declined.

Any job related to the establishment is seen as relatively secure, and even careers outside the civil service or other public institutions (i.e. hospitals, schools, libraries, research institutes, publishers, etc.) are sought after. According to a report posted by The Daily People titled “Young People Competing for Social Work Positions: Striving for Stability Even Without Establishment Status,” grassroots positions in local communities are becoming increasingly popular. In a county-level city in Anhui, more than 2,000 applicants competed for a mere 35 social work positions. Although these jobs do not lie within the establishment and also require intense grassroots engagement, regular overtime, and the completion of various miscellaneous tasks, they nonetheless offer stable income, a secure work environment, and a predictable career future in the midst of the economic downturn and the precarious conditions facing many firms. As a result, they are viewed as a lifeline by young people from certain educational backgrounds with test-taking abilities.

At the same time, the term “establishment” is itself increasingly losing its sense of stability. For example: In recent years, highly educated young people faced with stormy economic conditions have considered teaching credentials as a way to “climb ashore” into a relatively stable teaching jobs. However, according to a report by Beijing Business Today, at a 2024 work meeting, the Education Development Council in Beijing’s Fengtai District proposed that the district “enhance” its annual teaching evaluations and “put the results to use,” exploring the creation of a “teacher exit mechanism.” Fengtai thereby became the latest region to begin breaking apart the “iron rice bowl” of teachers, following Guizhou and Zhejiang.

The lingering impact of the three-year COVID-19 pandemic is also still being felt by young workers. In October, the media reported that several graduates from the class of 2024 were refused jobs for being within the so-called “pandemic cohort.” One business owner stated that they do not hire graduates from the 2022 to 2024 classes, explaining that, within their circles, it is widely believed that students from these years only took online courses and therefore lack adequate knowledge, making them unqualified.

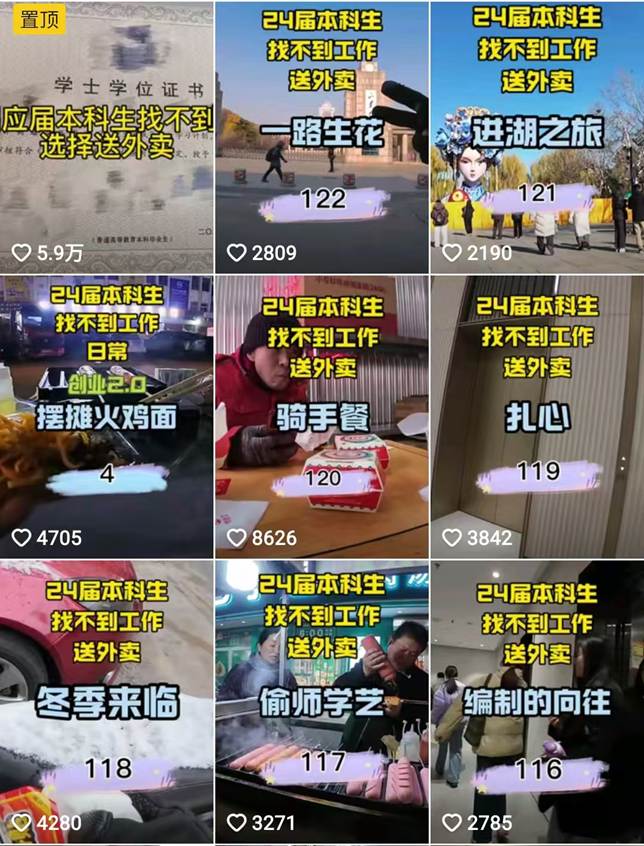

Continuing the trend from recent years, young workers lacking high levels of academic training have been leaving manufacturing and turning to various gig economy and service sector jobs such as food delivery, courier services, and content creation. Young workers interviewed by media outlets stated a belief that, since it is difficult to obtain a sufficient and stable income regardless, they might as well flee the strict hierarchies and complex social relationships of the factory, not to mention the mediocre pay and monotonous work. In addition, this year saw unemployed middle-aged workers from various sectors flood into gig platforms in great numbers, competing with younger workers. As a result, gig economy sectors like food delivery, which serve as employment buffers, have seen declining pay-per-task and worsening working conditions (See Part 3 for details).

To review: quality positions have grown increasingly scarce across the job market, the once-coveted “iron rice bowl” of jobs within the “establishment” is crumbling, those who already suffered three years of hardship during the pandemic now face discrimination in seeking employment after graduation, and workers who turn to the gig economy for “freedom” or temporary income find that pay has fallen. The popular online phrase, “Gen Z swallows the wretched shares of the era” has therefore come to reflect the sentiments of young people entering the labor market over the past few years.[2]

The deplorable labor rights conditions faced by young workers occupying the gray zone between study and work—such as “interns” from vocational schools, medical trainees, and graduate students—remained similarly dire throughout 2024.

In January, The Beijing News documented the case of a student with the surname Li. In 2018, while studying at Bijie Vocational and Technical College in Guizhou, Li had been recommended by the school for an internship at a telecom firm and was later hired as a full-time employee by the same company. However, when the company was later found to be committing fraud, Li was convicted of fraud as well, due to the nature of the work. According to lawyers, the school itself displayed gross negligence in its vetting of corporate partners and should bear the legal responsibility—regardless of whether Li entered the company as an intern or had been arranged employment there after graduation.

It is also common practice for such schools to collude with companies in supplying cheap intern labor to sweatshops. In April of 2024, Xinxinan Technical School in Yunnan was revealed to have been forcing early childhood education and hotel management majors to work on factory assembly lines performing monotonous physical labor for 11 hours a day. If the students refused, they would not be given their degrees. Moreover, the school also took a cut of students’ paychecks. The firm in question, Dongguan Zhengyang Electronics Factory, paid workers 23 RMB per hour, from which the school deducted 9 RMB.

Harsh internship conditions such as these contributed to several student suicides across the country in 2024. Furthermore, the absence of sufficient support also led to the mass stabbing incident described above (see Part 1). While it is important to unequivocally condemn acts of violence against innocent people, it is regrettable that public discussion triggered by such incidents has largely overlooked the long-standing abuse and violations of the labor rights of interns from vocational schools that laid the groundwork for such tragedies. This marks the fourth year in which we have compiled an annual review and the fourth year that we have called for vocational school students’ rights to be better protected. How many more tragedies will it take before we realize that, unless the root causes are addressed, the situation will only continue to deteriorate?

Early 2024 also saw several cases of suicide among medical residents. On February 2nd, a resident at the Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine committed suicide via carbon monoxide poisoning after being threatened with expulsion for “selling shifts” during Spring Festival in order to travel home for the holidays. On February 24th, during the Lantern Festival, a third-year graduate student and resident at Hunan Normal University named Cao Liping slit her own throat while on duty after being subject to constant pressure on the job. In March, a resident at Nanning’s First People’s Hospital who had reportedly been held back from receiving their certificate of residency also slit their own throat in their dormitory. Following these incidents, Professor Liu Jin, the designer of China’s medical residency system, remarked in media interviews that “medical students must be capable of working under fatigue,” dismissing the idea that the residency training system had become a cost-cutting tool for hospitals.

Among graduate students, practices such as filing joint complaints against advisors and taking conflicts to the public sphere became important strategies for academic workers in 2024. In January, 11 students from Huazhong Agricultural University submitted a 125-page letter accusing their advisor, Huang Feiruo, of academic fraud. As a result, Huang was eventually suspended. In April, 15 graduate students at Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications issued a joint accusation against their advisor, surnamed Zheng, of ethical and professional misconduct. The complaint stated that “the professor treats us like slaves,” accusing Zheng of forcing students to work overtime and disregarding their physical and mental health. The majority of students under Zheng’s supervision reportedly suffered from varying degrees of physical and mental health issues. Faced with such conditions, numerous social media accounts dedicated to discussing ways to deal with “bad advisors” have emerged and certain professors now notorious among academic workers have since become pariahs. In December, during a livestreamed lecture at Tsinghua University, Song Erwei of the Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, was confronted by students levelling charges of academic fraud, corruption, and student exploitation. Some students even tore down posters for the event in protest.

Finally, a labor rights monitoring organization also recorded a case of child labor involving a multinational corporation operating in China. A report released by the organization in early December revealed that Yunnan-based farms supplying coffee for Nestlé and Starbucks China were employing children. Adult workers at these same farms were also found to be working extremely long hours in harsh weather and were repeatedly exposed to pesticide-related health risks. Despite these dangers, these workers lacked health insurance and were barely even earning the minimum wage.

In summary, throughout 2024, the economic decline, employment discrimination, and labor rights violations combined to place increasingly severe pressure on young workers in China. From the growing instability of “establishment” jobs to the cutthroat competition of the gig economy and the long-standing violation of labor rights suffered by vocational school students, medical residents, and academic workers, the younger generation struggles to survive in the cracks. This situation is not simply an economic problem but is instead a pressing test of social equity and institutional reform.

[1] Translator’s Note: The specific terms used here are either “inside the system” (体制内) or “the establishment,” (编制), both of which imply a proximity to the bureaucracy. But they also include a number of positions that lie outside the formal government, such as corporate jobs at state-owned enterprises. Similarly, many positions that might be “public sector” jobs in other countries, such as social work, do not necessarily give one full “establishment” status. The exact implications of either term depends on the context. For example, the term “inside the system” is also used to refer to elites who have close relationships with high-level officials even if they themselves lie outside the government.

[2] The phrase “swallowing the wretched shares of the era” or, more literally, “eating all the black profits the era” (lit. 吃尽时代黑利) is a clever play on words that is difficult to translate in its entirety. The term “losses,” literally “black profits” (黑利), is implicitly understood in contrast to the colloquial term “bonus” or “dividends,” which is, literally, “red profits,” (红利). The implication is that young people today must reap the costs created by the earlier boom, suffering under the externalities generated by the profitability of the previous era.