Preface

Since 2020, an anonymous group of netizens has been coming together to prepare an annual review of labor struggles (or, in their terminology, “labor rights incidents”) and related social trends in China. The effort is led by Wechat User “Chiapas Eastern Wind TV” (恰帕斯东风电视机), who releases a call for contributions within self-described “pan-leftist” (泛左翼) circles. An ad hoc collective then forms, adopting a different tongue-in-cheek name each year to better avoid censorship: for the 2024 report they were named “Straw Mushroom Stewed Chicken” (草菇炖鸡); for 2023, “Iron Pot Braised Yellow Catfish” (铁锅炖嘎鱼), for 2022, “Three Fresh Ingredient Menzi Stall” (三鲜焖子大排档). Sometimes names are listed for editors. Sometimes no names are listed. Though there appear to be regular contributors who participate most years, the anonymous and collective nature of the project makes it difficult to determine. The collective is therefore an essentially crowdsourced team composed each year of members from vastly different backgrounds unified by a shared concern over the situation of ordinary workers. This team then distributes work, edits the ensuing material into a coherent report, and promotes it on social media. Aimed at a broad audience including Chinese liberals and progressives whose understanding is often framed in a language of identity politics and “labor rights,” the final report balances a number of viewpoints. As explained by the lead organizer, however, the authors share a broad consensus around several key goals:

- First, it hopes to convince liberals and progressives who have little concern for labor issues of the invariant importance of class struggle to social change.

- Second, it encourages those in the traditional labor left to more accurately grasp the intersectional complexity of working-class experience.

- Third, in response to a largely online left prone to overly philosophical speculation and doctrinal debate, it argues that aspirations for radical change must be grounded in a detailed understanding and analysis of the existing system.

- Finally, the authors have intentionally incorporated certain theories and practices related to “labor system reform” (工作体制变革) as a rejoinder to various mainstream ideologies that idealize nothing but work ethic.

Although the resulting document is somewhat inconsistent in terms of writing style and political analysis, given its crowdsourced nature, these annual reports have nonetheless served as the most comprehensive reviews of labor issues in China since the pandemic. To our knowledge, none have yet been translated into English. We therefore offer here the first installment in a full English-language translation of the most recent year in review, released at the end of 2024: “Keeping Each Other Afloat in a Difficult World: Taking Stock of Labor Struggles in 2024”. The original Chinese version, including the hyperlinks to each cited case, can be found here. Given that the report is roughly 100 pages, requiring many hours of translation work, we will be serializing the release. Individual sections will be launched on our blog every few weeks, likely until the end of the year (when the 2025 edition will be released in Chinese). If readers find the review useful, we hope to be able to mobilize resources to translate next year’s report more quickly.

-Chuang

Foreword

For the majority of workers, 2024 perhaps could not have been a worse year. At the same time, as the poet Bertolt Brecht once wrote: “Those who eat their fill speak to the hungry / Of wonderful times to come.”[1]

Beneath our feet, “the earth no longer produces, it devours.” At the border between our eyes and the horizon, “the sky hurls down no rain, only iron.”[2] Perhaps true despair lies not in things worsening but in our complete inability to care about all that has gone wrong already. Apathy and indifference spell the ultimate end of everything.

We have indeed observed each step taken for us to arrive here. The world is caught in a vicious cycle in which we tear at one another’s throats while racing to the bottom. Our woes accumulate so deep there appears no way out, and workers still lack sufficient means to halt the decline. Although new factors are emerging at greater speed, under the existing social structure, the turning point is indefinitely postponed further and further into an unforeseeable future.

Of course, we’ll still be using buzzwords: “trends,” “currents,” and “orientations.” But, with the help of this inventory, we hope to remind readers that, behind all the statistics and policy indicators are real people working, breathing, and suffering. For them, the key terms are “unemployment,” “debt,” “rent,” “poverty,” “illness,” “exhaustion,” “loss,” “injury,” “instability,” and even “homicide” and “death.”

We call for a genuine solidarity capable of transcending the tangled web of divisions that separates us from one another. This kind of solidarity would allow us to feel ashamed of the difficulties faced by others and therefore take practical action. We also call for patience and resolve. In the midst of adversity, we can use our own tools and materials to weave new methods in common.

We do not pray for a savior to bring fair weather. The future of the world continues to depend on what we desire and what we choose to do.

1. Winter has Come: Widespread Economic Stagnation

In 2024, China’s post-pandemic economic downturn showed no signs of reversal, as recession spread on all fronts.

From a macroeconomic perspective, key indicators such as the GDP deflator, the CPI, and the PPI all remained poor, the consumer confidence index reached a historical low, and exports continued to face mounting pressure from tariffs. Meanwhile, the contradiction between overcapacity and insufficient demand has only intensified further, even forming a downward spiral. The socioeconomic structure is showing obvious signs of change.

Pressure from the economic downturn is being felt in every industry. Sectors that are vulnerable to economic downturns such as manufacturing, retail, and services have borne the brunt of the crisis so far. High-paying industries like IT, real estate, and finance are also showing signs of fatigue. “Cutting costs and increasing efficiency” were the corporate mantra throughout 2024, resulting in recurring waves of layoffs and pay cuts. There has been no shortage of cases in which work has been suspended, production halted, and firms fallen into bankruptcy, leaving large numbers of workers without stable employment or source of income. In addition, the reduction in tax revenues that has followed from the downturn, compounded with the local government debt crisis, has significantly impacted traditionally secure “golden rice bowl” jobs such as those in civil service and the rest of the public sector.

The increase in the unemployment rate and erosion of income expectations have led to a comprehensive decline in consumption across society, further muting effective demand. Both at home and abroad, a large number of institutions and mainstream economists recognize that Chinese society is facing a real deflationary dilemma that requires urgent attention.

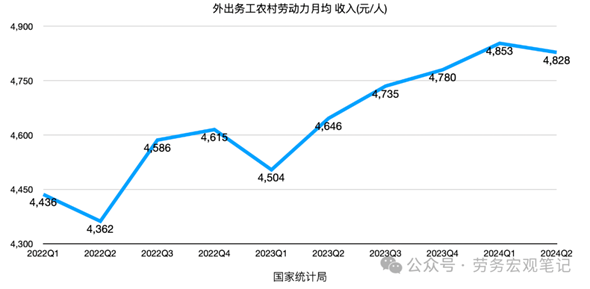

In the depths of this economic winter, the manufacturing and service sectors have suffered substantially, with many small- and medium-sized enterprises falling into distress or halting operations altogether. Reports from the manufacturing sector demonstrate that factories are having to slash prices and aggressively cut costs to win contracts, indicating the absence of virtuous cycles and sustainable economic mechanisms. Although the government has stressed the need to create new jobs, on the whole, the greatest concentration of new employment has been in low-income and precarious occupations (see Chapter 3 for details). In 2024, the number of migrant workers reached a historic high of 299.73 million.[3] The increase in the number of migrant workers may also be caused by falling prices for vegetables and other crops and the further deterioration of the rural economy. The question of how to increase incomes and improve the quality of life of migrant workers remains an urgent issue.

Even in the high-end automobile manufacturing sector, usually considered a key area for industrial upgrading, employees of both traditional and new energy vehicle firms are struggling

Throughout the year, emerging manufacturers such as HiPhi, Hengchi, Hycan, and Jiyue all announced one after the other that they were halting production. On February 18th, the first day after work resumed following the New Year of the Dragon, HiPhi held a general meeting where it announced it would pause production for 6 months. Hengchi also halted production at the beginning of the year, “aside from 13 security guards, there are only 40 employees working at Hengchi,” and “only 80% of the salary [of those working] is paid every month.”[4] In March, in order to salvage what it could from a sluggish sales environment, Hycan mandated that all employees (including those not in marketing roles) participate in sales activities. In June, Hycan employees then staged a protest, unfurling banners demanding that their shares in the company be refunded as promised. In November, worsening issues in production and sales led the company to freeze a portion of its equity, close its Shanghai branch, push through layoffs, and delay severance payments. In early December, Jiyue, which is a joint venture between Geely and Baidu, suddenly collapsed. Without warning, the firm announced that it was having operational difficulties and that it would be dissolved on the spot, leaving its more than 4,000 employees in shock. Following a confrontation with CEO Xia Yiping in which workers yelling workers encircled the CEO and demanded that he leave his passport behind to ensure he couldn’t flee overseas, workers then presented four demands: retroactive payment of their social security and housing fund contributions from October through December, payment of their December salaries, severance pay on the N+1 model, and the completion of outstanding hukou transfers.[5] According to a report by National Business Daily, Jiyue finally announced its compensation plan on December 19th, which did in fact promise employees “N+1” payouts, to be distributed in full by January 20th of the following year.”

Even better-performing NEV firms that have avoided work stoppages and production halts have nonetheless implemented large-scale layoffs and pay cuts.

On April 15th, Elon Musk announced that Tesla would be cutting more than 10% of its global workforce to reduce costs and improve productivity. The company’s China division was also impacted, experiencing layoff rates in excess of 10 percent. Cuts were even more severe in its charging station, sales, and marketing departments, where layoffs reached 40-50%. Leading domestic NEV firm Li Auto also conducted mass layoffs in May, officially cutting its workforce by 18%, affecting some 5,600 employees. However, many former employees claimed that the actual figure was closer to 10,000. Furthermore, some employees impacted by the layoffs then found that, if they disclosed that they had been laid off when they applied to other NEV firms, the salaries they were offered were reduced by 20%. To avoid facing these reduced offers, some workers opted to voluntarily resign, forfeiting their severance payments. There were also reports that severance payments for those laid off came up short. In response to widespread dissatisfaction, Li Auto simply chose to strengthen its security measures.

While the bankruptcies and layoffs among EV companies can be attributed to cutthroat competition within the sector, many traditional auto firms have found themselves facing unprecedented challenges due to their failure to adapt to the sweeping shift toward NEVs across the industry. In May, Dongfeng Honda laid off 2,000 employees, offering severance packages according to a “N+2+1” compensation model.[6] Another round of layoffs was then reported in August. The background to both waves was a sustained decline in sales. Between January and August of 2023, for example, new car sales dropped 19%. Facing intensified competition and ensuing pressures on its sales from domestic brands, Dongfeng Motor Group reported its first-ever loss in 2023, totaling some 3.996 billion yuan. Another joint venture automaker, Volkswagen China, also conducted layoffs. These were primarily directed at its imports division and affected nearly 100 employees. In the midst of the layoffs, the firm gave its employees two options: either relocate from Beijing to Hefei, or accept a severance package, with compensation as high as “N + 6”. In addition, luxury automaker Porsche China cut its workforce by 30%, including both direct and outsourced positions, with severance packages also reportedly following an “N +6” compensation model.

The wave of salary reductions has even spread to traditionally mid-to-high income sectors such as real estate, finance, technology, internet, gaming, and media and culture.

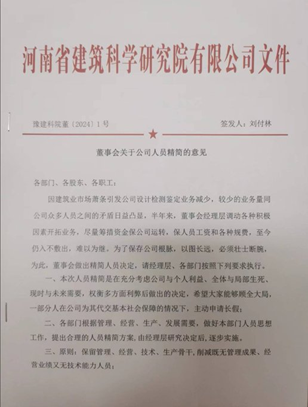

According to a report by Caixin Weekly, the sharp downturn in the real estate market over the past few years has had a severe impact on the construction industry, leading to widespread delays in pay-outs for projects and thereby threatening numerous firms with cash flow and debt repayment issues. Many large, central-state-owned enterprises have implemented layoffs and pay cuts, while small- and medium-sized private firms have gone bankrupt. As a result, many construction workers have seen their incomes suffer. On January 3rd, the Henan Provincial Academy of Building Research issued a notice stating that, due to the market depression and subsequent plummet in the volume of business, the company planned to “streamline” its workforce. It also urged employees to consider the conditions at hand and voluntarily apply for extended leave, offering to cover their basic social insurance contributions.

According to multiple media reports, the number of employees of the securities sector has fallen by 5% this year. Among the 42 market-listed banks that have disclosed their data, only 11 reported an increase in average employee pay, while 70% saw salaries decline. Rumors also hinted that certain positions at leading financial firm China International Capital Corporation (CICC) had seen their salaries cut by as much as 70%, which may have indirectly contributed to a workplace death. However, CICC told Red Star Capital Bureau, that the claims of layoffs, pay cuts, and suicides were all false reports. However, it is true that CICC, once ranked first in the industry in terms of its average salaries, has seen a significant decline in employee pay. Data demonstrates that average annual salary at the company was 1.1643 million yuan in 2021, but fell to 700,400 yuan in 2023, a cumulative decline of 39.84%.

Bloomberg reported that LONGi Silicon Materials, a leading photovoltaics firm, is planning to lay off nearly a third of its workforce to cut costs amid overcapacity and intense competition. In response to the report, LONGi stated that the photovoltaic sector is currently facing a complex competitive environment in both domestic and international markets and that the company has indeed implemented “relevant structural optimizations” to its employment to address the changing market. However, it estimated that only around 5% of roles would be subject to adjustment. LONGi is the world’s largest photovoltaics firm. And the photovoltaics industry is currently facing challenges such as overcapacity and declining profits. Since last year, production cuts and layoffs have become common. This year, several firms suspended their production lines. Media reports also revealed that, according to its employees, photovoltaics firm Hikvision has been undergoing a large-scale organizational adjustment since October, reducing its 32 R&D sections to 12 and “optimizing” more than 1,000 employees, according to estimates. The company denied that it had conducted large-scale layoffs and claimed to simply be making normal adjustments to its operational strategy.

The internet and gaming sectors have not been spared either, with many examples of employees being replaced by AI technology. On June 24th, rumors that “veteran gaming firm Perfect World would conduct its largest-ever layoffs” began to circulate on social media. A post to an internal employee network claimed that the company was planning on laying off more than 1,000 people. Both those within and outside the industry attributed the plan to the firm’s persistently poor performance.

Faced with recession and pressure from the new media industry, legacy media outlets have seen a significant decline in their operating revenues. Issues such as reduced page counts and shrinking advertising revenues have had a direct impact on employee salaries and benefits in the sector. Since last year, Shenzhen Press Group has implemented a wage withholding system and introduced stringent standards for annual performance evaluations. As a result, most employees have seen their year-end bonuses reduced, with only a very small number of high-performing staff eligible to reclaim their withheld wages in full. Recently, Shenzhen Special Zone Daily evenintroduced a wage deduction policy requiring reporters to meet a particularly demanding monthly quota. But limited space and the restricted scope of topics made it difficult for many journalists to meet the quota, resulting in severe salary reductions. After factoring in social insurance and housing fund contributions alongside the performance deductions, many were left with an actual monthly income of just 2,000 yuan.

Reports of salary cuts for professionals such as civil servants, teachers, and doctors have circulated online throughout the year, demonstrating that even those in traditionally secure “golden rice bowl” jobs in government or other public institutions may no longer have the same income stability and positive outlook.

Financial pressure within local governments has also impacted the salaries and benefits of public sector workers and civil servants. Multiple provinces and cities have reported civil servants suffering pay cuts. The Henan Provincial Development and Reform Commission posted on its website announcing reforms to streamline its staffing.[7]

On January 8th, the Harbin Institute of Technology posted a notice clearly stipulating that, following the requirements set earlier for lecturers, associate professors will now be subject to a six-year “up or out” evaluation period where their progress in the field is strictly monitored. The move sparked heated debate within the academic sphere. Meanwhile, places such as Beijing, Guizhou, and Zhejiang have also each begun exploring the establishment of exit mechanisms for teaching staff to prevent any individuals from “lying flat.” Cases of unpaid wages have also arisen in primary and secondary schools in various regions. For example, an incident was reported in Kaifeng, Henan, in which a primary school ceased classes due to unpaid wages. Meanwhile, in Nangong, Hebei, teachers at the Experimental Primary School held a protest at municipal government offices to demand their unpaid wages. Amid declining income expectations, rising childcare costs, and falling birthrates, the early childhood education sector is facing significant challenges. On May 8th, one netizen made public comments stating that a kindergarten in Langfang, Hebei had closed suddenly and, over the course of several days, parents had been demanding refunds and staff their unpaid wages. According to a report on Sohu, many early childhood educators faced with such circumstances are choosing to “self-rescue,” either by working side jobs to subsidize their expenses or by switching into careers such as customer service or work in nail salons, requiring them to reskill and adapt.

Within the healthcare sector, from October 24th to October 26th, employees at Jiaying University Medical School’s affiliated hospital in Meizhou, Guangdong, began posting online that, following 10 months of unpaid wages, the hospital would suspend services and declare bankruptcy. As a result, the workers were faced with sudden unemployment and financial hardship. Although the hospital promised that it would repay the wages and other compensation that it owed, it was unclear whether it could fulfill this commitment. In response, some employees lamented that even public sector jobs were no longer stable. Contract workers and middle-aged staff were faced with a particularly bleak outlook in the aftermath of the closure. On October 30th, a netizen posted a video online claiming that the township clinic in Baisha, Zhongmu County in Zhengzhou, Henan had not been paying salaries for 8 months. Employees gathered at the clinic to protest and laid siege to a black sedan, expressing their displeasure. Government officials in Baisha stated that salaries were being negotiated, and a solution was expected to come soon.

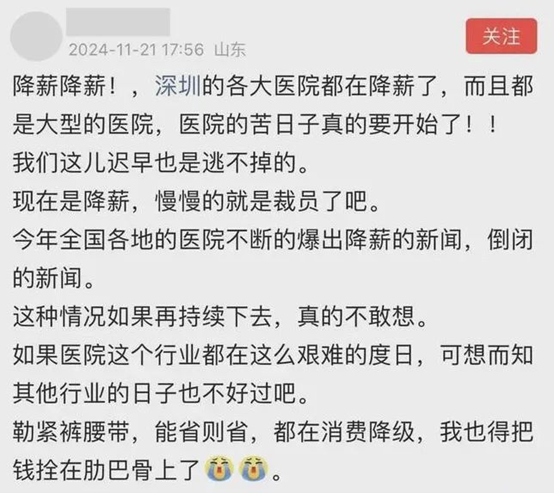

Even hospitals in first-tier cities have not been spared financial difficulties. According to a Caixin report on December 11th, several hospitals in Guangzhou and Shenzhen implemented pay cuts. The report also noted that the cuts mainly targeted performance-based pay and had spread to leading hospitals in the area. One factor behind the cuts was the promotion of the “Sanming Model” for integrated Medicare payments, which decoupled doctors’ salaries from both departmental revenue and the sale of drugs and treatments without providing adequate financial alternatives to hospitals.[8] In addition, the slowdown in economic growth and shrinking local government budgets have placed further strain on hospital finances, alongside ongoing cost-control reforms in the health insurance sector.

When individuals are put in extreme circumstances by the tides of history, malignant social events become difficult to guard against

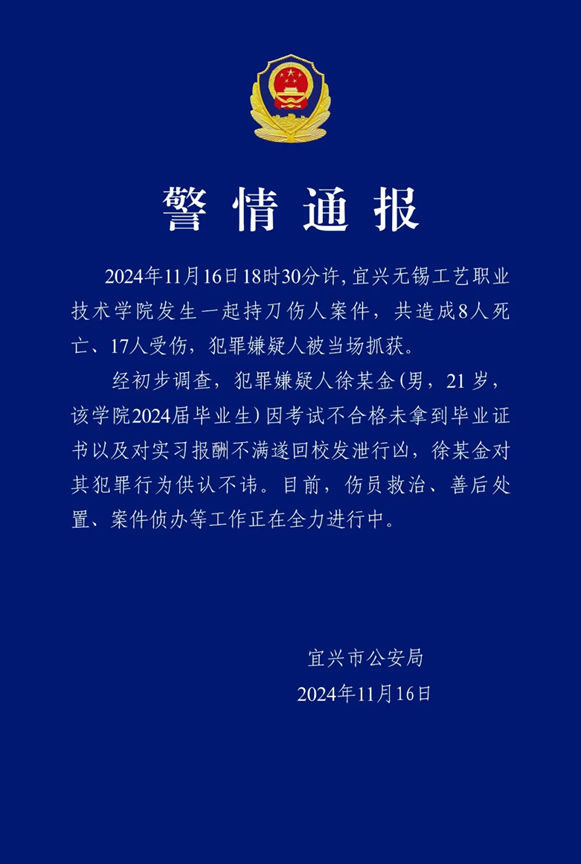

On the evening of September 30th, a brutal stabbing spree at a Walmart in Shanghai’s Songjiang District left 3 dead and 15 wounded. Unverified reports from netizens claimed that the attacker, surnamed Lin, had worked on construction sites under an individual surnamed Chen and was owed 30,000 to 40,000 RMB in unpaid wages. In August, Lin discovered that Chen’s company was registered in Shanghai and travelled there in search of him. But, having no luck, he ended up living on the streets. On the day of the attack, feeling that he had no way to go on living, Lin decided to slash out at people at random in the supermarket. On November 16th, another indiscriminate knife attack occurred at the Wuxi Vocational Institute of Art and Technology in Yixing, Jiangsu, resulting in 8 dead and 17 injured. The suspect, a 21-year-old surnamed Xu, graduated from the Institute in 2024. In an alleged suicide note circulated online, Xu alleged that he had been forced to work 16-hour days, had his wages withheld by the factory, and was denied his diploma by the school.[9]

The harsh winter has already arrived. Workers face deteriorating conditions. At minimum, the causes of this deterioration include the following:

First, many companies have chosen to respond to crises within the general economy and within specific industries by reducing their labor costs and shrinking employee benefits, placing immense pressure on their workers and treating them unfairly.

Second, in their attempt to cut costs as much as possible, individual departments within firms have conducted illegal firings and “disguised layoffs” under the banner of “reducing costs and improving efficiency,” leading to a substantial increase in labor arbitration cases across the country, according to data released by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security.

Third, the imbalance between supply and demand in the labor market has grown increasingly severe. Those looking for jobs face fiercer competition and are offered salaries far below their expectations and find that returns are not proportional to the intensity of the work.

Fourth, the turn to flexible employment and short-term contracts as a form of cost-cutting has resulted in significant reductions in social security and benefits for a portion of workers, exacerbating their financial difficulties.

Faced with these grim circumstances, the question of how to protect workers’ fundamental rights and interests is an urgent issue that both the government and society need to address.

[1] Bertold Brecht, “From a German War Primer,” translated by Sammy McLean, Poems, 1913-1956 (Methuen, 1976), 287.

[2] Bertold Brecht, “Finland 1940,”350.

[3] Translator’s note: This is our correction to an unclear statistic cited in the original. The new number is drawn from the 2024 Migrant Worker Monitoring Survey, available here: <https://www.stats.gov.cn/xxgk/sjfb/zxfb2020/202504/t20250430_1959523.html>

[4] 李星,“员工骤减至40余人,恒大汽车天津工厂:年初停产至今,工资发放80%”, 每日经济新闻, 2024-08-13. <https://news.qq.com/rain/a/20240812A04XU300>

[5] Translators’ note: The “N+1” model refers to a standard method of calculating severance pay in China, referring to the standard severance pay according to the number of years the employee has been with the company (the “N”) plus one month’s average salary. Also note that companies in China are legally mandated to pay into workers’ social benefit schemes alongside the workers themselves, usually in matching payments. The most important of these payments are to the social security system, which covers pensions, unemployment, medical, injury insurance, and maternity, and to the housing provident fund, which can be drawn on to assist in purchasing homes, renovating homes, making mortgage payments, and in some locales even making rent payments. Non-payment on the part of the employer is a common cause of workers’ protests.

[6] Translators’ note: The “N+2+1” model is similar to the “N+1” model, but with 2 months pay. The additional 1 refers to a bonus.

[7] Translators’ note: The announced streamlining plan includes extreme cuts of 50% of all staffing at various public institutions, excluding schools and hospitals. Notably, the cuts will include at least 30% cut of the coveted “bianzhi” or “establishment” quotas of employees on public payroll, and 10% decrease of “bianzhi” positions fully funded by the state budget.

[8] Translators’ note: For more information on the “Sanming Model” reforms, see: Zhong Zhengdong, Yao Qiang, Chen Shanquan, Jiang Junnan, Lin Kunhe, Yao Yifan, Xiang Li, “China Promotes Sanming’s Model: A National Template for Integrated Medicare Payment Methods,” International Journal of Integrated Care, 23(2), May 11, 2023. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.7011

[9] Translators’ note: In China, some lower-level colleges (usually referred to as “technical schools,” sometimes translated as “community colleges”) and even certain high schools send students to work long shifts in factories as “interns,” justified as a form of “vocational” training. The practice became more common over the course of the 2010s as a form of “flexible’ labor deployment that could mute the impact of rising labor costs. For an overview of the practice, see: Earl V. Brown Jr. and Kyle A. decant, “Exploiting Chinese Interns as Unprotected Industrial Labor”, Asian-Pacific Law & Policy Journal, Vol. 15(2), pp. 149 – 195