As part of our research on internationalist left currents in early 21st century China, we present the following translation of an article published on Initium in June 2019 by the mainland journalist and independent researcher Wu Qin, then writing under the penname Ban Ge. The piece is both a prime example of one influential current we find particularly promising, and an investigation of one key moment in the formation of China’s post-1990s political landscape: NATO’s bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, and the ensuing protests led by students in several of China’s major universities. Prior to this, left currents had begun to emerge from the ashes of 1989, mainly in the form of academic “New Left” critiques of modernity and workers’ resistance to the capitalist restructuring of state-owned enterprises.[1] Their internal differences had initially appeared muted within what was then called a “pan-left” (泛左) alliance against both the pro-market authoritarianism that dominated official politics and the pro-market liberalism that still defined its bourgeois opposition in those days. The “May Eighth Incident” (五八事件) of 1999 marked the injection of anti-American nationalism into the growing left critique of China’s integration into the global economy, an injection that gradually led to the left’s split into fiercely opposed nationalist and internationalist camps by the time of the 2008 Olympics and the anti-Japan riots of 2012. We will explore that division and China’s post-2012 anti-capitalist terrain in future pieces to be published here and eventually compiled into book form.

Wu’s article below digs back into the prehistory of that split by interviewing participants in the 1999 protests, including well-known intellectuals such as Wang Hui and Huang Jisu, along with several academics less familiar to English readers but currently influential in left circles. Although the latter were all politicized by the May Eighth mobilization while studying at top universities, not all of them ended up becoming nationalists—others ended up joining the ranks of the internationalist opposition. The author herself is clearly aligned with the latter camp and regards the rise of pro-state nationalism as a tragedy for China’s left, but here she lends a sympathetic ear in order to grasp the protestors’ motivations and discover why positions that seem ridiculous in the 2020s might have made more sense at the close of the twentieth century.

–Chuǎng

1999: An Embassy’s Blood, a March in Beijing, and Chinese Intellectuals at the Turn of the Century[2]

Wu Qin

Oh partisan carry me away,

bella ciao, bella ciao, bella ciao, ciao, ciao!

Oh partisan carry me away,

because I feel death approaching.

A Slovenian cinematographer known by his first name Matjaž, age 36, has come to China to shoot films many times in recent years. He comes across as the stereotypical mid-twentieth century Balkan man. Here in China, everyone calls him “Lao Ma.”[3]Not many people here have heard of Slovenia, so he usually says he’s from Yugoslavia.

“As soon as they hear that, many people start singing ‘Bella Ciao’ (theme song of the 1969 Yugoslavian film The Bridge [S-C: Most]),” Lao Ma says. Even though this song comes from Italy’s antifascist movement during World War Two, in China this film about guerrilla fighters became a symbol of socialist Yugoslavia, capturing the emotions of a generation.

The cultural life of the generation born right after the Mao era was somewhat drab, and the few dubbed socialist films created during the Cold War became treasures. When such guerilla films came to China in the 1980s, with their complex stories following fast-paced events, they were met with a warm reception in contrast with the one-dimensional plots and mechanical characters of earlier socialist films. After class at school, boys would reenact the guerrilla roles of Walter Defends Sarajevo [S-C: Valter brani Sarajevo] (1972), imagining themselves to be heroes dying a martyr’s death. They never tired of repeating among themselves the [secret passphrases] from the film: “I’d like to enlarge a picture of my cousin,” “The air is trembling, as if the sky were burning,” and “Yes, the storm is coming!” These films shaped the memories of a generation, leaving behind a sort of youthful homesickness, along with a sense of familiarity with Yugoslavia.

In 1999, when NATO’s combat aircraft were hovering above Belgrade, the emotions these movies once evoked in a generation were reawakened—and this time, the “hegemon” had become America.[4]

The Labyrinth of Memory

At 5:00 AM Beijing Time on May 8, 1999, NATO mounted yet another air attack on Belgrade. Five bombs falling from different directions penetrated the Chinese Embassy in Yugoslavia, and four bombs detonated. Three Chinese journalists—Shao Yunhuan, Xu Xinghu and Zhu Ying—were killed. After this news was reported in China, student protest marches erupted in every large city in the country, becoming known as the “May Eighth Incident.”

That same year, a soccer coach from Serbian Yugoslavia named Slobodan Santrač began working for the Shandong Luneng Football Club, then a team in the Jia-A League. A media writer by the online name Youguijun [“Mr. Spooky,” a reference to his political satire framed as ghost stories] recalls that at a match held not long after May 8, Luneng’s home field hung a banner declaring “Walter Defends Sarajevo.” The fans’ support for the football club resonated strongly with their support for Yugoslavia. After the match was over, the stadium enthusiastically sang “Bella Ciao.” Sports journalists interviewed Santrač, reporting he was deeply moved by Chinese responses to the NATO bombing. When the coach passed away in 2016, some news headlines still referred to him as “Walter.”

When I told Lao Ma about this interesting “misplacement” he scoffed, “These people don’t know how many ‘Walters’ the Serbian army killed during the siege of Sarajevo.”

In the 1990s, when the internet had not yet fully developed, ordinary people could only access limited information. Because of this, the Chinese public’s awareness of what had actually happened in the faraway Balkans was quite small. People didn’t know that Sarajevo, the part of Yugoslavia that had stirred up the most passionate feelings, had already left that soon-to-disappear country. At the time only Serbia and Montenegro remained in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. China was one of the countries most opposed to NATO’s air attacks, and when Yugoslavia’s civil war had broken out in the early 1990s, China’s official media had adopted a framework of “sovereignty” to denounce the West’s dismemberment of Yugoslavia, in contrast with Western mainstream media’s use of “human rights” to condemn the Serbian invasion of other nationalities.

When the Kosovo War broke out in March 1999, lighting the fuse for NATO’s bombing, the ethnic genocide created by Serbia in Kosovo was not widely known. Chinese media reports deemed Kosovo a “separatist force,” reflecting the Chinese authorities’ worries about ethnic unity in regions such as Tibet and Xinjiang. As a result, the Chinese public understood this mainly as a war of interference by the United States, the “world cop,” against Yugoslavia.

But, as China was just “getting on track with the world” (与世界接轨), its diplomatic strategy was not ambitious and its influence on the international order was far weaker than it is today. Song Nianshen, who now teaches history at Maryland University in Baltimore, had just graduated college in 1999 and was working at the Global Times. He remembers that at the time foreign reporting in the Chinese media was quite limited and the Chinese public lacked awareness of international affairs. The war only sparked widespread notice after NATO’s bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Yugoslavia.

Song Nianshen remembers that at noon on May 8, while celebrating his father’s birthday, he received a phone call urgently calling him back to the paper’s office. Global Times’ Yugoslavia correspondent Lu Yansong was the only Chinese journalist inside the embassy who survived the bombing and had been on the wire all night sending back first-hand information regarding the suffering of his countrymen. That edition of the newspaper had massive sales. This incident also prompted many media workers to recognize that the Chinese public’s demand for international political news was far greater than they had imagined.

In 1999, dramatist Huang Jiadai was in her first year of university in Shanghai. She personally experienced the May Eighth Incident at her school, when her indignant classmates began marching, preparing to “make history.” Later she produced two theater performances about the Kosovo War in Belgrade and Shanghai.

In her play, a character discusses changing high school politics exam questions: “Who was the great leader who led the liberation of the Yugoslavian people?” Answer: Tito. But, the question was changed later. “Who is the national hero who preserved the unity of the Yugoslavian Federal Republic, opposed hegemony and bravely took a stand as the people’s hero?” Answer: Milosevic.

In the view of Chinese people educated in the 1990s, Slobodan Milosevic was the defender of the country’s unity and a hero opposing American hegemony. Because the textbooks were written in this way, only such answers could receive those two points on the politics exam. Those two points also consolidated China’s glorious socialist friendship with Yugoslavia.

The strange thing is that throughout the Mao era, Yugoslavia had never been China’s “old friend.” In fact it was just the opposite: The CCP had used the country as the poster child for the evils of revisionism. In its official propaganda, Yugoslavia was denounced for betraying the international socialist movement and embarking upon the road to capitalist restoration, and for being a “running dog” that the American-led hegemony spent several billion US dollars to maintain. After Nikita Khrushchev came to power and the Soviet Union became China’s enemy, the CCP listed Khrushchev’s renewal of friendly relations with Yugoslavia as being among his revisionist crimes, and after the Sino-Soviet split, Moscow’s relationship with Belgrade grew even closer.

According to Wang Yan, a professor at Beijing Foreign Studies University’s Institute of Foreign Literature, by 1973 films such as Walter Defends Sarajevo and Bridge had already become “privileged information,” imported with many films from the Western capitalist world to be watched by the CCP leadership. Deemed a “cancer of individualistic heroism,” these films were not made available to the general public. It was not until after the official end of the Cultural Revolution in 1977 that cinemas began to screen them.

In the spring wind of “Reform and Opening-up,” all of the previous “struggles over political lines” dissolved into old grudges. In the 1980s, the Sino-Soviet split that began in 1960 was no longer remembered as an ideological divide between Stalin and Khrushchev, but had become a vaguely unified expression of opposition to the Soviet Union’s “Big Country Chauvinism.” China’s market reforms cited Yugoslavia’s path of “socialist self-management” as a key model for emulation, and Yugoslavia’s guerrilla films, released in China against this backdrop, became an emotional undertone in the collective memory that became difficult to erase.

In people’s memories, therefore, the friendship between China and Yugoslavia suddenly became one that had continued without interruption. They now felt that Yugoslavia had recognized the Soviet Union’s “hegemonic face” even earlier than China. This late-recognized esteem lent popularity to a piece of political gossip: Mao Zedong had once praised Josip Broz Tito as being “forged in iron”![5] Chinese people’s image of their “old” friend was thus reconstructed: The people of Yugoslavia had the courage to say “no” to the powers that be. First they heroically resisted fascism, then they refused to bow down to the Soviet Union’s might, and now they were standing up to the hegemony of the United States.

In the 1990s, this indomitable impression that Tito, the guerrillas and Yugoslavia had left on this generation, coupled with that sense of intimacy derived from the country’s old films, was naturally transferred to the “Federal Republic of Yugoslavia”—Yugoslavia’s Serbian-dominated successor state after the Socialist Federal Republic’s dissolution in 1992. Years later, when some Chinese leftists became further disillusioned with American liberal democracy, and nostalgic for the Socialist Bloc, they even declared Milosevic “the last Bolshevik.”

In Walter Defends Sarajevo, the old watchmaker Sead looks at his daughter who was killed in Sarajevo Square with other citizens, fully aware that, if he were to claim her body, the German troops would shoot him from behind too. And yet still he chooses to step forward. At the second the German troops raise their guns, the people of Sarajevo behind the watchmaker step forward one by one. For playwright Huang Jisu, born in the 1950s, this is the most memorable scene of the movie.

When he recounted this scene to me, Huang said, “This spirit of ‘saying no to power’ moved me deeply.” He remembered that in 1999, before the Chinese embassy was hit, the news channels were airing footage of the bombing of Belgrade. His son, who at the time was in primary school, asked him, “Which one is more powerful: the US or Yugoslavia?” This question bothered him for some time: “Why didn’t my son ask, ‘Who was in the wrong?’ Instead he asked, ‘Who is stronger?’” He believes that to some extent this was a result of the educational system since the 1980s, which taught the doctrine of meritocracy. People had begun to abandon the ideals of fairness and justice and instead pursued success and power.

In 2000, Huang Jisu[6] went on to write a stage play that stirred up the Chinese intelligentsia, Che Guevara, which celebrated the spirit of Guevara’s doomed “fewer than one hundred guerillas who challenged the world’s strongest imperialist war machine.” The play opens with NATO’s bombing of Yugoslavia. The people of Belgrade wear targets on their chests as they stand on a bridge, the planes roar, and on the screen above the stage appear many small white concentric circles—targets. An offscreen pilot announces, “Target locked, target locked, preparing to fire.” For most viewers, this evoked the scene mentioned by Huang Jisu in Walter Defends Sarajevo.

“If put in a concrete historical context, I think there is a certain distance between the emotional experience of the time and objective reality,” says Huang Jisu, looking back on the experience after twenty years. “The international community’s interference in an ongoing humanitarian disaster is really an issue worthy of deep discussion. But at that time, regardless of whether it was Yugoslavia or the United States, both were just symbols entering Chinese people’s emotional experience.”

Empathy toward Yugoslavia was a process of internalizing external problems. After the end of the Cold War, China was exposed in the imbalanced world system dominated by the US, and NATO’s bombing of the embassy shattered Chinese people’s image of the “beacon of democracy.” They then started the soul-searching for China’s own place in the world, bringing the Balkan conflict into their own affective framework.

The Moment of Trauma

“That was my first time to see students rush onto the podium of Xianghui Hall (the largest auditorium of Fudan University and a symbolic meeting place), filled with grief and indignation as they shouted, ‘Down with US imperialism!’ The whole auditorium repeated the slogan with growing enthusiasm. You could only see this type of scene in movies from the 1960s and ‘70s.” That scene had left a deep impression on Zhang Xin, now associate professor at East China Normal University. In 1999, he was a second-year graduate student at Fudan while also working part-time as a fudaoyuan 辅导员 [often translated “counselor” but functioning more as political advisor and liaison for school authorities and the Communist Youth League] for undergraduates. “After the assembly, the students paced up and down on the lawn in front of the auditorium for a long time, unwilling to leave,” Zhang said, remembering the scene on that May 8.

By the end of that night, protesters had already gathered at the entrance of the US Embassy in Beijing, where they pulled up paving stones from the sidewalk and threw them at the buildings. The consulates in Shanghai, Shenyang and Chengdu had also been surrounded. In Chengdu, the protesters even set fire to the consulate general’s home. In cities without a consulate, protesters targeted McDonald’s to air their grievances.

“Down with US imperialism,” “NATO = NAZI,” “the Chinese people will not be disgraced,” “wipe out national humiliation, resist the aggressors”—signs bearing such slogans could be seen everywhere among the angry protestors. Zhao Zhiyong, who now teaches at the Central Academy of Drama’s Department of Dramatic Literature, was a student at Wuhan University that year. Wuhan didn’t have a US consulate, so instead his classmates marched several hours to the French consulate in Hankou to protest, he recalls. One classmate’s shoes were worn through by the walk and he walked barefoot back to Wuchang.[7]

That year, people were still immersed in fantasies about “integration into the world” (融入世界) that had begun to take shape two decades earlier with the Reform and Opening-up, where the US had appeared as an ideal society symbolized by Coca-Cola, McDonald’s and Hollywood. In 1986, China had begun the lengthy process of negotiations for accession to the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which later would become the WTO. At the time, “joining the World Trade Organization” was abbreviated as “joining the world” (入世), tying it to these broader social fantasies and promising ordinary people that the good life was just around the corner.

On March 26, 1999, the second day of the NATO attacks on Yugoslavia, the White House hurriedly announced that the then-premier Zhu Rongji would visit the United States on April 6. Zhu Rongji’s trip to the US was for the purpose of advancing the WTO talks. This was the first time in fifteen years that a Chinese premier had visited the US. Zhu attempted to advance all sorts of compromises in exchange for American support, but ultimately came back empty-handed, less than a month before the events of May 8.

With the drastic changes of Eastern Europe and the breakup of the Soviet Union, the integration of the world economy proceeded unimpeded and there was no space for any alternative worldview to capitalist globalization. After the initial market-oriented reforms accelerated in the 1990s, China’s economy was being rapidly integrated into the global market.

Wang Yan believes that Chinese views of the West moved away from the romanticism of the 1980s to a more realistic view with embodied experiences in the 1990s.

“At that time, ‘joining the WTO’ entered the stage of preliminary preparations, which required China to obey the international economic order.” Wang recalls that during this period, several large foreign companies, including Motorola, set up shop in Beijing. Beijing Automobile Works (BAW) and US-based Jeep created a joint venture, and many deskilled older workers were laid off as a result. “The ‘America’ from photos and videos suddenly became realistic in Hujialou, Chaoyang District (the location of BAW), and the Chinese people were finally getting first-hand experience of ‘the world.’” After reforms to the property system began in 1992, the restructuring of state-owned enterprises led to “societal growing pains” such as mass layoffs and the division of society into rich and poor.

“The US was symbolically internal to China’s market reforms,” Huang Jisu recounts. “As China’s most important frame of reference for the Reform and Opening-up, the collective consciousness naturally blamed the United States for any societal problems that arose in China. That incident [i.e. the protests] was also a response to internal pressures that motivated an explosive ‘anti-imperialist’ response.” Several books promoting nationalist sentiments had become mass-market bestsellers, such as China Can Say No (中国可以说不), first published in 1996. All the societal changes of the 1990s had set the emotional stage for the final May of the century.

The ruins of China’s Belgrade embassy were like another lingering wound to the Chinese people: In the history of China’s foreign relations, the 1840 Opium War had begun a “century of humiliation,” with one indignity after another being reflected in this bombing. May 1999 coincided with the eightieth anniversary of the May Fourth Movement, when Chinese people had claimed the “national right to self-determination” advocated by US President Woodrow Wilson after World War I. China had attended the Paris Peace Conference as a victorious ally, but instead of returning the defeated Germany’s holdings in the Jiaozhou Peninsula to China, the great powers gave them to Japan. The outcome of the Paris Peace Conference triggered a large-scale nationalist mobilization, comprised primarily of students, against imperialism and the Beiyang government [the First Republic of China]. This began the shift toward “enlightenment” and “national salvation” (救亡) in modern Chinese history. The theme of “enlightenment” had been frequently revisited since the socialist era, but “national salvation” was not reactivated until this moment in 1999. The humiliating experience that “there is no diplomacy for a weak nation” was like a specter from the past eighty years floating into that May of 1999. A new wave of anti-imperialist nationalism, originating in the 20th century Third World and colored by left-wing progressivism, also emerged at this point after “the end of history.”

A touchstone for recalling this time frequently cited by intellectuals is the play The Field of Life and Death (生死场) by the renowned director Tian Qinxin(田沁鑫). The play is adapted from a 1930s novel by the famous left-wing woman author Xiao Hong(萧红), set in the War of Resistance against Japan—the Chinese front of World War Two. In May 1999, when the play premiered in Beijing, the historical scenes of fighting against Japanese imperialism were understood by the audience to represent the current opposition to American imperialism: At the play’s crescendo, anti-American slogans resounded through the audience. The people reawakened to their hundred tragic years of poverty and weakness as spring turned into summer, shattering their fantasy of being accepted into the world again following the “end of history.”

At Peking University, which has been the birthplace of Chinese social movements and ideology since the May Fourth Movement of 1919, now students at the Triangle raised the slogan: “Don’t take the TOEFL, don’t take the GRE, unite our hearts and souls to defeat the American empire!” The Triangle is located in the heart of Peking University and was once the most important convening space on campus, known for its concentration of student activities—the space that all the demonstrations of the 1970s and ‘80s had to pass through. By the late 1990s, the Triangle had already been plastered over with advertisements for TOEFL and the GRE. In 1999, media worker Hua Shaohan was a sophomore in the Department of Archaeology at Peking University. He remembers the rapid rise of New Oriental in those years. (New Oriental was established in 1993 and became China’s largest English training company.) The company offered TOEFL and GRE preparation courses, its success embodying elite students’ dream of studying abroad in the US.[8]

But the end of the Cold War closed off many options, leaving no other choices. “Don’t forget, the place where we went to get US visas was the same old embassy that students attacked during the May Eighth Incident.” Recalling the trauma of that day, Wang Pu, who was born in 1980 and now teaches at Brandeis University in the US, feels that although his generation had begun to reflect, they were still docile subjects of the ideology of globalization, deceiving themselves (intentionally or not) into believing that history was always linear.

Two Types of Nationalist Movements

However, many students at the time believed those May protests led by universities across the country seemed to be a result of official manipulation that was inciting and exploiting nationalist sentiment to consolidate the legitimacy of the ruling party.

Ten years earlier, as spring was turning into summer, the “June Fourth” Tiananmen Movement broke out and ultimately ended in bloodshed. The upheavals of the East European socialist countries never arrived in China. Nevertheless, the ruling CCP faced multiple crises of legitimacy.

On May 8, 1999, as the photos of the three journalists who were killed continued to flash on TV, the mass media diffused feelings of grief and anger throughout society. In the recollections of many students, the protests in those days were largely organized by the Communist Youth League committees of their universities, in a very orderly fashion. Every school was assigned a quota, eggs were distributed to be thrown at the consulates, busses picked students up and brought them to the embassy areas, where the street in front of the English and American embassies had designated demonstration areas, and they were even required to conclude the demonstration at a designated time and return to the buses so the next school could arrive and begin their own demonstration. Because of this, students who joined the demonstrations that year were despised by the “clearheaded” as “the brainwashed.” In some people’s memory, at that time many university teachers with a liberal stance warned their students in class against being manipulated.

Rapidly advancing market reforms diverted political attention, as the humanistic spirit that had flourished in the 1980s entered a downturn amid the restructuring of state-owned enterprises, as many people from the state sector “jumped into the sea” of private enterprise. Democracy had not arrived, but people were completely “liberated” from the system and became “economically rational people” in the market economy. The idealists who had once struggled for freedom and democracy now began to “drop the baggage” of June Fourth in the wave of marketization. At the same time, nationalist education in universities and secondary schools was in full swing, with the apparent intention of preventing another movement like the one in 1989 from emerging. Against this background, researchers have argued that the Chinese government instrumentalized students’ anti-imperialist and nationalist sentiments to meet its agenda of clearing away the political gloom from the collective memory.

However, simplification of and contempt toward that wave of nationalist sentiment cannot accommodate the heterogeneity of the movement, nor does it help explain the ambiguity of the nationalism expressed in that context.

Many students with an unclear political stance view the movements of 1999 and 1989 as being the same, just a carnival to release youthful hormones. In the script of her play, Huang Jiadai wrote, “At the time [in 1989], students from the universities rode motorcycles past our [secondary school’s] sports fields, carrying large banners and yelling as us, ‘little sheep!’ [because we weren’t participating in the Tiananmen Movement] Today we can yell back! I’m so excited…. Now it’s finally our turn to make history.” Wang Yan, however, felt the 1999 protest was performative and full of revelry, like an imitation of the 1989 protest.

“Many Peking University students took to the streets to protest, not so much out of patriotism as out of a political catharsis of the post-‘89 era,” said Shi Ke, who was a fourth-year student there at the time. Now a poet and theater worker, in 1999 Shi was a thoroughly committed liberal. “Liberal discourse, rather than nationalist sentiment, prevailed at Peking University throughout the post-’89 era.” He recalls that after the Tiananmen Movement, the university’s political clubs were banned. The tacit agreement between government and schools was that “protests do not leave school,” so being allowed to take to the streets in 1999 became a “way out.”

These people took to the streets as a mockery of May Eighth Movement, unreflectively inheriting the cognitive framework of the 1989 generation in believing that the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia was an American effort to liberate people from authoritarian states. The bombing of the embassy came as spring turned to summer, just approaching the tenth anniversary of the June Fourth Incident, so long-suppressed political discontentment became mixed into the wave of anti-imperialist nationalism, and both sentiments were vented together.

In this sense, nationalist rhetoric opened up a discursive space for resistance movements, helping them develop their own agendas under the protection of official rhetoric. However, when the authorities realized that the “nationalist movement” had gone beyond its designated issues, they began to discourage it, calling a halt to all protests after two days, and the armed police and People’s Liberation Army began to protect the US and UK embassies in Beijing.

Zhang Xin remembers that after the students had obtained permission from the school to stage an orderly march on the street, school authorities later told him (as a fudaoyuan counselor) to dissuade the students from attending. Huang Jiadai remembers that the school often backtracked, saying they would organize the students to march in the afternoon but then would cancel immediately. Many universities even organized lectures to teach students about “rational patriotism” and “responsible nationalism.”

When the central government tried to calm things down and accept the Clinton administration’s apology and offer of compensation to the families of the deceased, the public’s anger surged once again. Driven by the language of resisting imperialist hegemony and defending sovereign interests, a clear disconnect emerged between the nationalist sentiments generated from below and the state’s own diplomatic strategy. The tensions between state and society of 1989 were not transcended through the patriotic rhetoric of 1999, as many observers have claimed, but continued to haunt the May Eighth Movement.

After the bombing of the embassy, the People’s Daily Online immediately opened the “Strong Nation Forum” (强国论坛) without awaiting approval from the Central Propaganda Department or the State Council’s Information Office. Lao Tian, a left-wing scholar born in the 1960s, was among the first batch of users of this forum. He remembers that articles from different voices began to appear on there. The most striking were criticisms of the authorities by nationalists. In addition to their dissatisfaction with the authorities’ insufficient defense of national interests, the forum also had reflections on the approach to foreign relations taken by leaders in the Reform Era. Lao Tian believes that as soon as Deng Xiaoping had departed from Mao Zedong’s vision of an international order centered on the Third World, entering a honeymoon period with the US. The West had become a social blueprint for the reforms. In 1999, he says, left-wing criticism of officials began to surface, with many people beginning to diagnose and reflect upon the international order in the forum, and the memories of Mao-era anti-imperialism began to revive after many years of silence.

This nationalist sentiment driven by anti-Americanism reached its climax two years later, following September 11, 2001. After the embassy bombing incident of 1999, the South China Sea aircraft collision incident of April 2001 had once again set off Chinese people’s anger toward the United States. When “9-11” arrived at the same year, many Chinese people viewed that terrorist attack on the US as “retribution for evil deeds”—a result of America’s interference in the affairs of other countries. The development of the internet made it easier for people’s emotions to converge and collide. For a time, Osama Bin Laden was romanticized by Chinese netizens and became a “anti-imperialist hero.” Zhang Zhe, in his third year as a student at Peking University at the time, recalls that he was eating in the cafeteria when the news was announced about the Twin Towers being hit, and many of the students put down their chopsticks and applauded.

This kind of nationalism has been described as “popular nationalism” by Johan Lagerkvist, a scholar of China studies at Stockholm University in Sweden. In Lagerkvist’s view, the 1990s gave rise to a new generation of nationalists in China. In contrast to the “state nationalism” instrumentalized by authorities, the spontaneous nationalism of the masses has become a force to be reckoned with for China’s foreign policy elites, at times requiring foreign policy to change in response to a wave of nationalism. Wang Yan also believes that the 1999 embassy bombing signaled that nationalism was no longer monopolized by the state, and instead had become a highly dynamic popular force—although it may not always be positive.

An Epochal Rift

In 1999, Wang Hui, a scholar of intellectual history, was the editor-in-chief of Dushu, China’s most influential intellectual periodical at the time. After the embassy was bombed, he organized a symposium under the auspices of Dushu, only to find that his contemporary intellectuals, who had been born in the 1950s and 1960s, were not prepared to respond to the event. “Discussions on universal human rights were central,” he said. Wang recalls that on hearing one scholar recite from Kant, he didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. Wang Yan too recounts that, while auditing a seminar at Peking University’s School of Law, he heard a professor lecture on the opposition between historical sovereignty and the abstract notion of “Man,” describing the US intervention in Kosovo as a “just war.” His intellectual identification with universal values came into strong conflict with the emotional “humiliation and injury” experienced as a result of the embassy bombing.

“The bombing of the embassy just made me walk out of the ‘80s,” says Liang Zhan, who now works at the Institute of Foreign Literature at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. In 1999, he was a graduate student studying Habermas. In fact, the incident was a turning point in the intellectual trajectory of not only Liang, but also of many other Chinese left-wing intellectuals born in the 1970s. This taste of imperial hegemony provided an emotional experience for theories developed after that day.

For many intellectuals, the 1980s were the best era. After the end of the Cultural Revolution, the intellectual and cultural fields were waiting to be rebuilt, setting off a “cultural fever.” The state-led intellectual liberation movement to expose and criticize the Cultural Revolution was in full swing, providing intellectual and institutional preparation for the market reforms. At the same time, intellectuals also led a “New Enlightenment Movement” driven by the “universal values” of liberalism, vowing to liberate “Man” from the yoke of collectivism. These two parallel currents of thought both led China’s direction toward modernization. In that historical context of the 1980s, the socialist road was seen as “anti-modern,” while the West (especially the United States) symbolized the “modern” other. The spring and summer of 1989 marked the climax of 1980s liberal thought, with the images of tanks and dead students becoming historical footnotes, plunging the intellectual stratum into endless mourning, pity and nostalgia for that era.

Liang Zhan remembers that in 1999, when NATO began bombing Yugoslavia, he had a similar emotional reaction as most of the “post-‘89” generation in his circle: They weren’t clear about what the war was about but, regretting their own “unfinished democratization,” they imagined that the US was bringing freedom to another authoritarian state. Huang Jisu, who was working at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences at the time, also recalls the Chinese intellectual community’s one-sided support for the US at the beginning of the war. He sympathized with Yugoslavia and submitted an application to the police station for permission to hold a demonstration prior to the May Eighth Incident, hoping to show the outside world that there were differing voices in the Chinese intellectual community. But the demonstration was not approved.

When the Chinese embassy, a symbol of national dignity, was bombed by NATO, it was like a slap in the face. The anger at America’s bullying became merged with the sense of humiliation at being betrayed. “The issue of the global order was the most serious problem of our generation, and the starting point was May 8, 1999,” Liang Zhan said. Wang Pu also believes that from the Kosovo War to China’s accession to the WTO and on to September 11, international politics had left an enduring mark on the intellectual trajectory of the generation that entered the intellectual world at the turn of century.

Marketization in the 1990s revealed various problems, making the Western model increasingly suspicious to some intellectuals. In the mid-1990s, a split began in Chinese intellectual circles, signaled by an essay by the “New Left” flag-bearer Wang Hui, titled “Contemporary Chinese Thought and the Question of Modernity.”[9] In a generation of intellectuals shaped by liberalism, China’s New Left became an ear-piercing voice.

The intellectual community living in the hesitation and disorientation of 1990s society was ignited by the May Eighth Incident, and the rift widened quickly. The sovereign state’s interests made young intellectuals recognize the hypocrisy of the ideology of liberal democracy in an imbalanced world system. Although they shared the traumatic memories of June Fourth, they stood in opposition to the generation that was perpetually stuck in the 1989 moment, as they had become disillusioned with the universal values that the US stood for. Those stuck in ‘89 accused the young nationalists of attacking the unhealed “liberal wounds” under the banner of “anti-West”, not only betraying the movement from a decade ago but also building a foundation for it to be forgotten from the collective memory. In this sense, the May Eighth Incident had already gone beyond its status as a diplomatic incident: It also carved a deep rift in the emotional foundation of that era’s intellectuals.

The Kosovo War opened up the debate between “sovereignty and human rights” as an important issue in the global intellectual community. It tore apart the Western intellectual community in 1999 and today has echoes in the Venezuelan coup and the Syrian war. The “human rights camp” represented by Habermas supported NATO’s humanitarian intervention in the ethnic cleansing of Kosovo, while the “sovereignty camp” represented by Noam Chomsky criticized the US-led interest groups’ ambitions to shape the new world order in the post-Cold War era. The rift in the Chinese intellectual community was to some extent an echo of the division torn in Western intellectual communities during this war, but it revolved around China’s internal historical experiences.

Liang Zhan became disenchanted with Habermas during his research process and believed Habermas had departed from the left position of the Frankfurt School. In the September 1999 issue of Dushu, Wang Hui published the article “Habermas and Imperialism,” by Zhang Rulun from the Philosophy Department of Fudan University, criticizing the ideological trap of the human rights discourse. As Wang explained [in a later interview], human rights undoubtedly served as an excuse for NATO’s eastward expansion in that war. The article was heavily criticized among liberal intellectuals. In 2001, Habermas visited China, setting off an additional round of discussions on sovereignty and human rights in Chinese intellectual circles. Xu Youyu, a liberal intellectual who participated in those discussions, later published an article complaining that “some New Left scholars in China no longer recognize values such as freedom and human rights, and are only imitating Western left-wing intellectuals’ criticism of capitalism and market economy.”

When anti-Americanism replaced class struggle, becoming an inescapable question for Chinese leftists active in the era of globalization, how could they square the sovereign state perspective of their nationalist affective framework with the internationalist one from the history of the communist movement, in which “the proletariat has no homeland”? This was a question that puzzled me during interviews with participants in the May Eighth Movement. British historian Perry Anderson pointed out that from the French Revolution until World War Two, nationalism was always an expression of bourgeois liberalism, while socialists representing the working class had always been internationalists. This situation began to reverse after World War Two: In the anti-imperialist nationalist movements of the Third World, the world’s exploited poor classes used nationalism as the main basis for their opposition to First World colonialism and imperialism. Nonetheless, influenced by the 1960s Chinese revolution (and Maoism), the wave of global revolutions against imperialism was not always carried out within the framework of sovereign states. Whether it was the Black Panther Party in the US, the Maoist parties in India, or the Japanese Red Army, all were in direct conflict with their own governments. But in the era of global capitalism initiated in the post-Cold War era, anti-imperialist ideology has often bound leftists to sovereign states, especially in late-developing countries. The line between leftists and conservatives has become increasingly blurred.

Huang Jisu, who was born in the 1950s, believes that for younger generations, the world system and the class structure are one and the same, and after 1999, Chinese left-wing intellectuals used anti-imperialism to engage in wider social criticism. Wang Pu, born in 1980, believes that this is the most difficult question for Chinese intellectuals of his generation, and is in fact a contradiction that has never been overcome. “Our generation’s vision of the world comes from the West, lacking in internationalism, but instead where the national experiences of economic growth and ‘the peaceful rise to power’ have played a decisive role.” In his view, the left shaped by this historical structure has often appeared ambiguous.

This is probably the great dilemma left to intellectuals in the era of global capitalism. In an era when capitalism pervades everything, post-Cold War liberal ideology sees sovereignty as the greatest obstacle, and human rights discourse is instrumentalized for the core’s plunder of the periphery. “Internationalism” changed course and was overtaken by the neoliberal economic order, and in this web-like economic order, only sovereign states have a seat at the table. When confronting this economic order and defending peripheral countries from becoming the economic colonies of the core ones under the rules of this game, it often seems that the left in late-developing countries have no choice but to reaffirm the standing of sovereign states. Yugoslavia has now become another point of reference for the Chinese left: After the federation’s dissolution, the republics became increasingly marginalized and cannibalized by the core of the international order.

In that moment in 1999, “sovereignty over human rights” became an overwhelming ideological discourse in Chinese society. In the era of capitalist globalization, the left wing has become increasingly aligned with the interests of the state. Chinese liberal intellectuals who were unwilling to leave behind the 1980s were crushed beneath the dual weights of the state and popular nationalism, ultimately being thrown into the dustbin of history.

Epilogue

For many intellectuals, the 1999 embassy bombing became a landmark event in the rise of Chinese nationalism, regardless of whether they were supportive or wary of that wave of movements. After that, China experienced a decade of economic expansion. Nationalism accompanied the new national experience and, after abandoning the affective framework of “the century of humiliation,” it was finally replaced by the splendor of a “great rejuvenation” at the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Wang Yan and Huang Jisu both see 2008 as the watershed moment at which China’s nationalism shifted from left to right. As China has gradually moved out of the “Third World,” China’s nationalism no longer regards “terrorism” on the peripheries as an anti-imperialist ally, but instead evaluates ethnic groups that have not been domesticated by the international order according to the binary framework of “civilization vs. barbarism.”

Now, twenty years after the May Eighth Incident, the US-China trade war is raging and flows of Chinese capital are blockaded by the US-monopolized information system, once again setting off a spark of anti-American nationalism among both intellectual circles and ordinary people. It seems like an echo of May 1999, but the US long ago ceased to be a beacon for a better way of life and more often plays the role of competitor to China, the emerging power in the same old game governed by the same rules. Although the rules have not changed since 1999, China has increasingly been adapted to them and alternative economic orders are no longer an object of imagination. Even after Trump took office and the US acted like a rule-breaker, China paradoxically strove to defend the existing order.

What is intriguing is that, in the current wave of anti-American nationalism stirred up by the trade war, “national capital” has come to replace both “the embassy” (the late twentieth century’s symbol of national sovereignty) and “the proletariat” (the Mao era’s symbol of internationalism) as the affective framework for today’s anti-American struggle. At the same time, in recent years the trends of thought that have attempted to use class discourse as an alternative to nationalism have suffered a heavy blow.[10] But the trade war has clearly generated more emotional appeal to Chinese left intellectuals as a topic of interest than the rout of those left-wing movements. We cannot predict how this “new cold war” will unfold, but it undoubtedly raises new questions for today’s intellectuals: In the interplay between the international world order and the domestic social structure, how should intellectuals—especially left-wing intellectuals—reevaluate their own positions?

Translators’ Notes

[1] For an overview of the 1990s political landscape, see relevant sections of The Left in China by Ralf Ruckus (Pluto, 2023), The Peasant in Postsocialist China by Alexander Day (Cambridge University Press, 2013), One China, Many Paths edited by Wang Chaohua (Verso, 2005), and “Swimming against the tide: Tracing and locating Chinese leftism online” by Andy Yinan Hu (Simon Fraser University M.A. thesis, 2006). We will explore this background in our forthcoming book on internationalist left current in early 21st century China. This has also been schematically in our works “Red Dust” and “A State Adequate to the Task” (both from issue 2 of the Chuang journal).

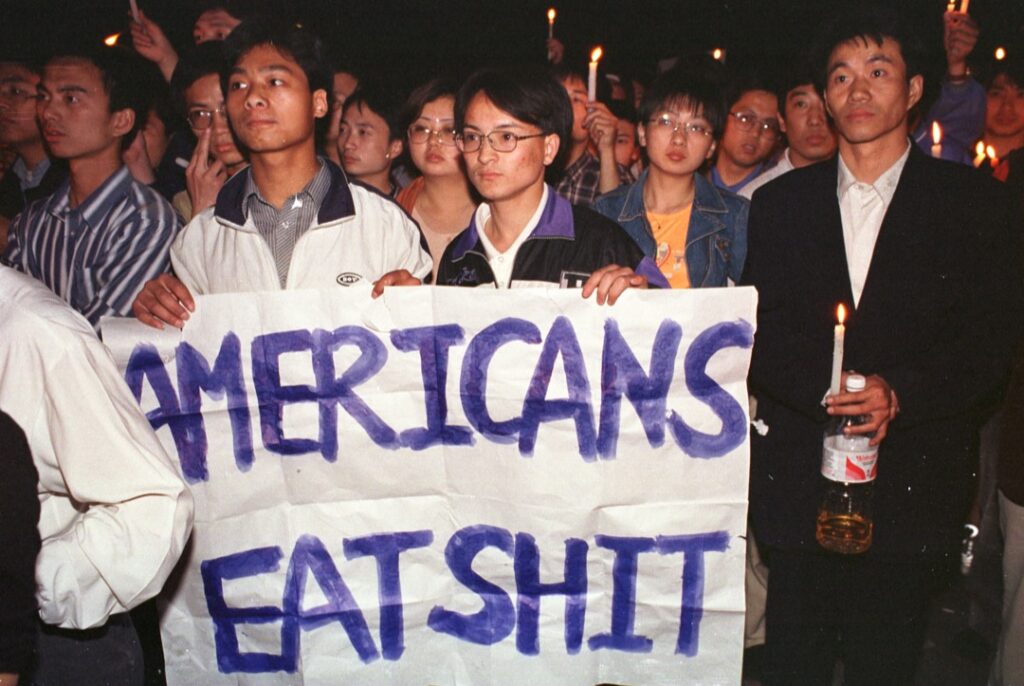

[2] This is a more direct translation of the original Chinese title (1999:大使館的血、北京的遊行,與世紀之交的中國知識分子 ). Header image: On May 9, 2001, to commemorate the NATO bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, about 200 overseas Chinese demonstrated in downtown Belgrade to demand an end to NATO air strikes on Yugoslavia. (Photo by Sovfoto/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.)

[3] The Chinese surname Ma, meaning “horse,” was given to Matjaž because it sounds the same as the first syllable of his given name. Lao(meaning “old”) serves as an honorific. (Matjaž’s actual surname could not be retrieved.)

[4] In the film, the “hegemon” against which the Yugoslavian guerrillas had fought was Nazi Germany, and later Chinese observers cast Yugoslavia as bravely resisting the Soviet Union’s hegemony within the socialist world as well (discussed below).

[5] The Chinese transliteration of Tito is 铁托, the first character of which means “iron.”

[6] See “Che Guevara: Notes On The Play, Its Production, and Reception” by Huang Jisu (translated by Xie Fang), in Debating the Socialist Legacy and Capitalist Globalization in China (edited by Xueping Zhong and Ban Wang), New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

[7] Wuhan is comprised of three main areas (previously cities) separated by the Yangzi River: Wuchang, Hankou, and Hanyang. Wuhan University is in Wuchang.

[8] The story of New Oriental is dramatized in the 2013 film American Dreams in China (中国合伙人). It begins with the founders as cheeky college students in the late 1980s, channeling the anti-authoritarianism of Red Guards, but now to challenge their teachers’ received wisdom about the evils of American society (“What do you know? You’ve never been to America!”). This pro-American attitude paradoxically develops in a nationalist direction throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s, as the protagonists seek to arm other upwardly mobile young men with the English language ability and self-confidence to achieve wealth and power on the global market while modernizing their own nation.

[9] The essay (当代中国的思想状况与现代性问题) first began to circulate informally in 1994, then was revised for the left-leaning literary journal Tianya in 1997, and finally updated for the book Rekindling Dead Ashes (死火重温) in 2000. Rebecca Karl’s English translations were published in the journal Social Text’s issue on “Intellectual Politics in Post-Tiananmen China” (Summer 1998) and Wang Hui’s English book China’s New Order (2003).

[10] This refers to the state repression of leftists, labor activists and feminists since 2015, peaking in the Jasic Affair of 2018 and its aftermath in 2019—explored most recently in “The End of an Era: Labor Activism in Early 21st Century China” (Chuang blog, April 2023).