This post is the seventh in a series of periodic summaries of highlights from Chinese-language news and social media, offering some analysis of economic trends and the changing character of class struggle in China. Through these posts, we hope to give English readers a broader sample of the discussions taking place across the linguistic and digital divide. In addition, we recommend a few recent English-language publications at the end. (If you notice mistakes or any important story that we missed, please contact as chuangcn@riseup.net and we can add it to next month’s post.)[i]

Highlights from Chinese Left Media: FoodThink (食通社)

In order to give readers a window into the discussions happening on independent, left-leaning media platforms based in mainland China, we’ve decided to begin summarizing highlights from different platforms in each of our news posts. This time we’ve chosen one called FoodThink (食通社). We’ve chosen this platform in part because, although we’ve previously written about and translated articles from topically broader platforms such as Companion (同时), Society of the Khazars (哈札尔学会/ 哈轧尔学会), Research on Modern Capitalism/ MaGeZhuang (郑姿妍/ 马各庄), East Wind Chiapas Radio/ Power Drill (恰帕斯东风电台/ 电钻), Groundbreaking/ Tootopia (破土/ 土逗公社), and Turbulent Stream (激流), and from platforms more focused on feminism and labor struggles such as Chili Tribe (尖椒部落), New Generation/ WeiGongHui (新生代/ 微工汇), and Factory Stories (工厂龙门阵), we’ve never really explored any of those dedicated to rural issues, agriculture, or the environment.

The peak of left engagement with rural issues was in the 2000s, when rural struggles over land grabs, pollution and corruption prevailed among China’s class antagonisms. (Those struggles and left interventions were explored in our article “Gleaning the Welfare Fields” in the first issue of our journal.) Following the strike wave of 2010, many of those left activists turned their focus toward industrial labor struggles, and more recently toward other types of urban issues. But over one-third of China’s population still lives in the countryside or has roots there. Rather than simply disappearing, the rural antagonisms of the 2000s have taken different forms in response to the consolidation of a new food system, involving the capitalist development of agriculture, industrial destruction of land and water, and the increasingly dramatic effects of global warming. And a few of China’s leftists have continued to investigate these antagonisms and try to support rural people.

Given the practical constraints of working in China, and the institutional gulf that has divided cities from the countryside ever since the socialist era, most of this engagement has taken “food” as a point of entry. Left-leaning food activists have investigated the effects of global warming and capitalist development on the remaining communities of smallholding farmers, ranchers and fishers who still produce food, along with those recently displaced by the agrifood industry. They’ve tried to support those communities’ efforts to survive by forming cooperatives and marketing their products outside the dominant food system. Aside from this topic being politically safer than directly supporting rural resistance to environmental destruction, for example, it has also been seen as the most obvious existing link between rural and urban communities that could be mobilized.

FoodThink describe themselves as “a community for sharing knowledge and writing about sustainable food and agriculture, launched and managed by a group of companions who have been involved in the practice and research of agriculture and food for many years. We believe that our food system might achieve health, good taste and sustainability only when consumers understand the sources of their food, and when those who practice agroecology can have markets and social environments that are fair and just.” The blog was launched in 2017 and its podcast went live this March.

In July and August, FoodThink hosted online and in-person discussions with smallholding farmers and ranchers about the effects of global warming on their livelihoods, and published several articles on this topic. Like many other countries, China has been undergoing a heat wave with the highest temperatures on record combined with droughts and floods this summer (also discussed in the regular news sections below), and these have been especially hard on many of the nation’s food producers.

“Understanding Climate Change from Deep in the Terraced Hills of Guilin” (July 20)

FoodThink reporters visited Quanzhou County in southwestern Guilin, famous for its karst landscape and terraced paddy fields, to interview a millennial named Dai Yunyun. Dai had returned to his rural home, after eight years of office work in Shenzhen, to become an organic rice farmer, using traditional varieties and methods long abandoned by most of his neighbors. He had been the first in his family to attend university, and the first in his village to return after graduating. One thing Dai showed FoodThink was that most of the few locals who continued to farm had been taking the famous wet-rice terraces, sculpted through generations of collective ingenuity, and converting them to dry land for tangerine production, since the latter could yield ten times the income in today’s market.

More concerning is the increasing unpredictability of weather patterns. Dai’s septuagenarian father had learned from his own parents when to plant, when to harvest and so on, and these dates on the traditional agrarian calendar had remained consistent throughout his life until the past ten years or so. In general, temperatures have grown noticeably warmer: It used to snow most winters, fish ponds freezing to the point that “you could play basketball on them,” but now in the rare cases of snow, it melts as soon as it hits the ground. This means pests and plant diseases have had more opportunities to spread. Even worse, rain patterns have become more extreme and unpredictable, leading to drought one year followed by flooding the next, with devastating consequences for rice yields and farmers’ income.

Although Dai’s traditional varieties of rice also suffered, he discovered that at least it survived this year’s drought better than his neighbors’ GMO rice and especially the tangerine trees. He also benefited from allowing weeds to grow along the banks of his rice terraces, in contrast with his neighbors who sprayed everything with herbicide. This covering decreased damage to the fields caused by increasingly severe rainstorms.

“How Is Drought Impacting Ranchers’ Livelihoods in Inner Mongolia?” (July 25)

In early July, a FoodThink reporter visited a Mongolian pastoralist family using the Chinese surname “Ma” in Dorbod Banner, 80km north of Hohhot. They met the family through an NGO researching water security and the effects of drought on animal husbandry in the region. After decollectivization in the 1990s, the family received pastoral rights to about 10,000 mu (667 hectares) of grassland. Since there is no river in the area, the livestock (sheep and cattle) get most of their water from wells, or from a truck used to transport the well water to more distant pastures.

Luckily the Ma family’s wells have not been affected by the drought, but the grass has. The declining quantity and variety of vegetation have left the sheep emaciated and sickly to the point that none have been marketable yet in the first half of this year, whereas they normally expect to sell over 100 sheep and a dozen cows over the course of two seasons. Meanwhile prices have fallen 30% from last year’s 1,100 yuan per sheep to a mere 700 yuan this year. In addition to fresh grass, the family’s 50 cows also eat 160 kilos of hay each day, purchased from elsewhere due to the shortage of grass in the area, and the drought has driven up hay prices such that the family is now paying 2,400 yuan more per month than last year.

Since 2008, the local government has taken a series of measures to protect the grassland from ever worsening drought and overgrazing, imposing restrictions such as allowing ranchers to raise no more than one sheep per 30 mu (2 hectares) and one cow per 150 mu. These seem to have slowed the desertification process but not stopped it, while doing little to offset the impact on ranchers’ livelihood.

The effects of global warming on Inner Mongolia as a whole are illustrated by the new record number of drought years: nine droughts in the past ten years, in contrast with the previous record of six droughts throughout the decade of the 1950s. This June and July the regional government seeded the clouds 1,206 times but only managed to increase rainfall by 3 millimeters. Mr. Ma says he and other Mongolian ranchers he’s talked to are skeptical about the sustainability of cloud seeding, which is toxic, costly and wasteful of energy. The authors suggest looking instead to “the wisdom of traditional nomadism” for ways to adapt.

Other stories on the effects of climate change on agrarian communities:

- “Inescapable High Temperatures, Ungrowable Sweet Potatoes” (August 11)

- “Is the Massive Flooding of Farmland a Natural Disaster or a Manmade One?” (August 23)

Other articles of note include two film reviews:

“When a Morality Play Is Cast Upon the Silver Screen, the Real Countryside Returns to Dust” (July 14)

After watching Return to Dust [隐入尘烟, 2022, dir. Li Ruijun], I felt a bit nonplussed. After all, the last film that took a female celebrity’s homely acting style as its selling point was The Story of Qiu Ju [秋菊打官司, 1992, dir. Zhang Yimou], centered on a rural northwestern woman defined by stubborn resistance. Thirty years later, I never would have expected that Chinese peasants could be transformed into such silent, passive and moralistic figures on the silver screen. Yet the most influential critics in China have rushed to praise the film as “an ode to the soil,” “a romantic epic rooted in agrarian China” that “depicts the internal logic and sacred glory of peasant life.” Is it society, the film industry, or its audience that has regressed? […]

The use of wheat as a metaphor for peasants’ relationship with the land is nice, but rural people are not wheat. Nor have silence and passivity in the face of exploitation been their way of life for the past few millennia, and I hope that this film will not reinforce such stereotypes. As for those viewers who have felt moved by the film, after drying their tears, maybe now is the time for them to begin learning about the actual countryside and its residents?

“Jurassic World Dominion: The Spectacle on the Screen and the Ecological Disaster Off the Screen” (July 4)

As a diehard fan of the Jurassic novels and films who also happens to understand something about genetic technology and agri-food systems, I actually think the introduction of locusts into the plot both fits the series’ narrative logic–that people’s arrogant confidence in biotechnology will ultimately devour humankind itself–and is particularly relevant today: What worries the scientists in the film has already happened repeatedly in real life. […] Just think, for instance, of the superweeds generated by the use of GMO crops and herbicides, the destruction of biodiversity wreaked by the monopolization of the seed market, the environmental and health problems caused by agrochemicals, the antibiotic resistant bacteria created by the meat industry, etc., etc.

Two items touching on the capitalist transformation of produce markets:

- A series of photos a woman has been taking since her childhood growing up in a wet market in Shanghai, where her migrant parents have been working since the 1990s (July 21)

- A podcast episode discussing “Will Produce Markets Continue to Exist in the Future?” (August 20)

Also see this report-back from a FoodThink intern about her three months of rural fieldwork: “In the Countryside, We Don’t Talk about Dreams or Emotions, We Just Live” (August 5)

Summaries of Other Highlights from Chinese News and Social Media

July

Women Imprisoned for Fleeing Domestic Violence

On the evening of July 6, the poet Yu Xihua (余秀华) posted a statement on Weibo, ending her six-month relationship with Yang Zhuce (杨槠策) and stating that Yang had slapped her “hundreds of times.” Yang admitted to at least one of these incidents.

While Yu was fortunate enough to escape the relationship and publicize what had happened, other women under similar circumstances have chosen riskier ways out. One report recounted the stories of two survivors of domestic violence who left their husbands and lived with other men, only to be charged by their husbands for the crime of “bigamy” (on the grounds that their new relationships constituted de facto marriages), for which the women were sentenced to 4 and 6 months in prison.

Why didn’t they apply for divorce? Theoretically there are procedures under the law against domestic violence, but legal loopholes have invited no less horrible tragedies. Things have only gotten worse after the introduction of a 30-day cooling-off period for divorce, during which the authorities are supposed to reject applications if either of the spouses withdraws it, or if both spouses do not apply for the divorce certificate in person. The official explanation for this is to reduce “impulsiveness” in divorce, but it only increases the chances for domestic violence to escalate.

Unpaid Worker Dies of Heat Stroke

This summer, capitalist global warming has led to some of the highest temperatures on record in multiple countries including China, which has seen “the most severe heatwave recorded anywhere” according to weather historian Maximiliano Herrera—along with the droughts and floods discussed above and below. However, this has not prevented bosses from ordering workers to continue laboring in the heat. While some workers who suffered from heatstroke were fortunate enough to receive medical treatment and stay alive, others were not. Wang Jianlu (王建禄), 56 years old, passed away while returning home after finishing work as a day-laborer on a construction site in Xi’an, where he was trying to make enough money for his son’s college tuition. Wang’s previous year’s wages as a member of a construction work-team had gone unpaid with no resolution because of his lack of a contract, common for construction workers in China. As a result, Wang had turned to unstable day labor: That way, at least he could be sure that each day’s wage would be paid.

Official reports acknowledged the difficulty facing workers who hope to receive insurance to pay for treatment in case of heat stroke. Before this accident went public, Wang’s family couldn’t even contact the construction company to ask for his wages. After his death, however, they reached an agreement, with the company paying for funeral expenses and full compensation.

Another Bid to Save the Economy through Lofty Regulation

Problems keep emerging for China’s economy in the sphere of capital circulation. July’s total social financing volume change plummeted to 756.1 billion yuan—down 85.4% MoM and 29.7% YoY—despite M2’s increase, meaning that enterprises trapped in pessimistic expectations were reluctant to take loans even after money circulation accelerated. They were right to feel that way since retail sales, an indicator of consumer confidence, were kept aground for both the MoM and YoY rates.

To address this, the central bank announced another rate trimming in a bid to support loan demands, and the State Council went for a high profile to promote 19 policies, one of which will allow local governments to back the purchase of homes as they see fit. (More on this below.) The State Council also sent out working groups to economically significant provinces in an effort to push these policies through.

Home Buying to Prop Up the Property Market?

To save the stagnant economy from further recession, local governments have been desperate to set out more incentives for home purchases, which remain one of the main drivers of consumption in China. In our April news summary we mentioned that some banks in Guangdong secretly relaunched a “relay loan” where children would be responsible for repaying loans when parents default. While this loan structure was abandoned in less than a day, a variant of this policy has become common throughout first and second-tier cities. Instead of burdening the entire family with a mortgage loan, homebuyers have another option of spending all of their Housing Provident Fund (公积金)—a welfare fund exclusively for home purchases deducted from wages—for the down payment.

However, people were quick to realize possible legal and financial consequences of this scheme. On the one hand, there is a question of property if a house is bought with the whole family’s money. On the other hand, there is a contradiction between the need to stabilize real estate markets and the fact that at current prices, which reflect home values as a speculative asset, it is impossible for individual buyers to purchase homes in order to simply live in them. While leveraging family assets might make a purchase possible, declining expectations for future price increases are leading wealthy speculators to attempt to cash in by selling homes. While demand for newly-built homes remains high, the number of “second-hand” homes that have been purchased in the past year has been dropping dramatically.

Homeowners Take to Collective Delinquency for Their Future Homes

Real estate’s risks in China are related not only to those in need of a home, but also to owners already in mortgage. Starting in July, a wave of protests spread nationwide where homeowners threatened delinquency if their homes remained unavailable after the down payment was completed. One cause of this has been the pre-selling mechanism: homebuyers have to fork over cash before the properties are even constructed, while property developers receive vast streams of essentially interest-free financing. What’s more, buyers in China must typically pay the full price upfront, based on designs, renderings, demonstration units, and promised delivery dates.

Although major banks claimed minimal impact from possible delinquencies, the authorities were quick to provide specific loans to developers. Nevertheless, over 300 cases of these protests have been archived as of late August, and the list seems to expand.

In English, also see: “‘We Own It’: The Chinese Homeowners Squatting in Unfinished Buildings” from Sixth Tone.

Hebei Bank Protests

The People Respond to People’s Daily Attack on “Lying Flat” with Regard to COVID

On July 14, the People’s Daily released an editorial titled “Our Covid Prevention Policy Is the Most Economical, with the Best Outcome” (我们的防疫措施是最经济的、效果最好的). The editorial praised the “Dynamic Zero-COVID Policy” as being sustainable and economically sound, while dismissing strategies of “herd immunity” (whether through infection or vaccination) or “lying flat.” Notably, official critique of “lying flat” (躺平) culture, a proletarian youth response to overwork and a lack of opportunities, has been applied to laxity with regard to covid. This re-use might have underestimated the appeal of lying flat in general, as commenters’ responses to the editorial were quite caustic, before being quickly censored. Some comments we noted included the following:

“What should I say? I can only applaud.”

“Why is every other country so foolish that none of them want to learn our policy?”

“How much is spent for COVID testing nationwide per day? Local fiscal expenditure for this is related to our daily life. Don’t disguise it as ‘free testing’.”

“Since you claim it’s the most economical, please disclose all the cities’ financial books. Prove it with data.”

“Who earned the most in this pandemic? Do you dare to look into it and expose them?”

“Everything you claimed must be correct? Common people’s feeling is the real thing. Look at all the defaults and unemployment…”

“And now we have to pay our medical insurance for 30 years…”

“Does this only account for the cost of fighting the pandemic? How about the cost of unemployment, and bankruptcy of small and medium enterprises?”

Another Stark Contrast between Class Experiences

This January we published a partial translation of the record of a construction worker’s life in Beijing that had gone viral alongside that of the first omicron case in Beijing––a wealthy individual whose contact tracing details revealed trips to jewelry stores, private cars, and theater visits. In July, accounts of similarly stark contrasts emerged.

With a rise of covid cases in Chengdu, people noticed that official reports omitted names of places the infected people had visited, instead providing only street addresses. It was quickly revealed that these were the addresses of government institutions, where some civil servants who had tested positive left their offices on time (a luxury compared with most employees in China) or even earlier, and then spent their leisure time with various options: restaurants, hotels, ping-pong clubs, luxury stores, and socializing.

Meanwhile, contact tracing details of another positive case in the fifth-tier city of Longnan, Gansu illustrate a very different type of life: working on a construction site, buying steamed buns from a street vendor for lunch (apparently eating little else for the four days on record), returning to the day-labor recruitment spot to look for another job, visiting his mother in the hospital, and then returning to his low-end apartment for the night.

Bragging about Wealth, Bragging about Modesty

Similarly, a government official’s son flaunted his wealth on his WeChat Moments feed (朋友圈). He claimed to have tea worth 200,000 yuan (about 29,655 USD), attended a meeting wearing an Omega watch, and paid for his seventh house in full. The local government confirmed most of these as facts, but insisted that this was simply a personal act of boasting.

Around the same time, someone posted a video on Bilibili titled “I’ve been back home in my village for three days, and my second uncle has already cured my psychological burnout” (回村三天,二舅治好了我的精神内耗). The producer’s uncle, who walks with a crutch, had to drop out of school in his youth after a country doctor’s fever medication left him disabled. Afterward, he learned to repair agricultural equipment and furniture to make a living. According to the producer, he then “became the second happiest person in this village” –– by this, the video means that he is the kind of person who never looks back and carries out his responsibilities with modesty. Of course, the happiest people are those who do not have such difficult experiences to overcome.

This preaching of “good vibes only” (正能量) is built on shifting sand. To name a few points that were brought up by online critics: The uncle is silent throughout the video, and all narration is coming only from the producer, who does not explain why, as a disabled person, his uncle could not get his share of legally mandated welfare payments. After repeated questioning, the producer said that he felt uncomfortable putting his uncle on the spot, so recorded the video in a different location, which led to further questions about whether the uncle existed or not.

Nevertheless, one fact is certain: class divisions disguised by moral disgust serve as a good way to attract public attention, and some take this as a model for generating income.

August

Heat Waves and Power Cuts

Southeastern China has been undergoing over a month of high temperatures and low rainfall. While coastal regions have suffered without rain that is usually brought by typhoons, inland regions around Sichuan and Chongqing have faced even more serious heat. For a period of three weeks in mid-August, nighttime temperatures in Chongqing did not fall below 90F/32C, with mid-day high temperatures averaging 106F/41C and reaching as high as 110F/43C. Shorter periods of similarly high temperatures in July, combined with low rainfall, led authorities to reduce reservoir levels, resulting in a situation by August in which hydropower production (which is the province’s largest source of electricity) was not sustainable. Electricity limitations began on August 14, and all power supply to industrial production in the entire province of Sichuan was cut off by August 20. Individual home users also experienced power cuts. This combination of high temperatures and lacking electricity lead to a number of heat-related deaths that has still not been accurately accounted for, and many never be released.

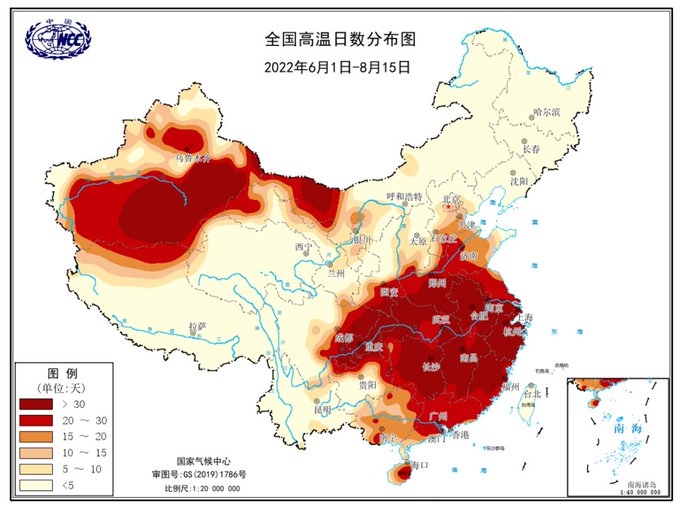

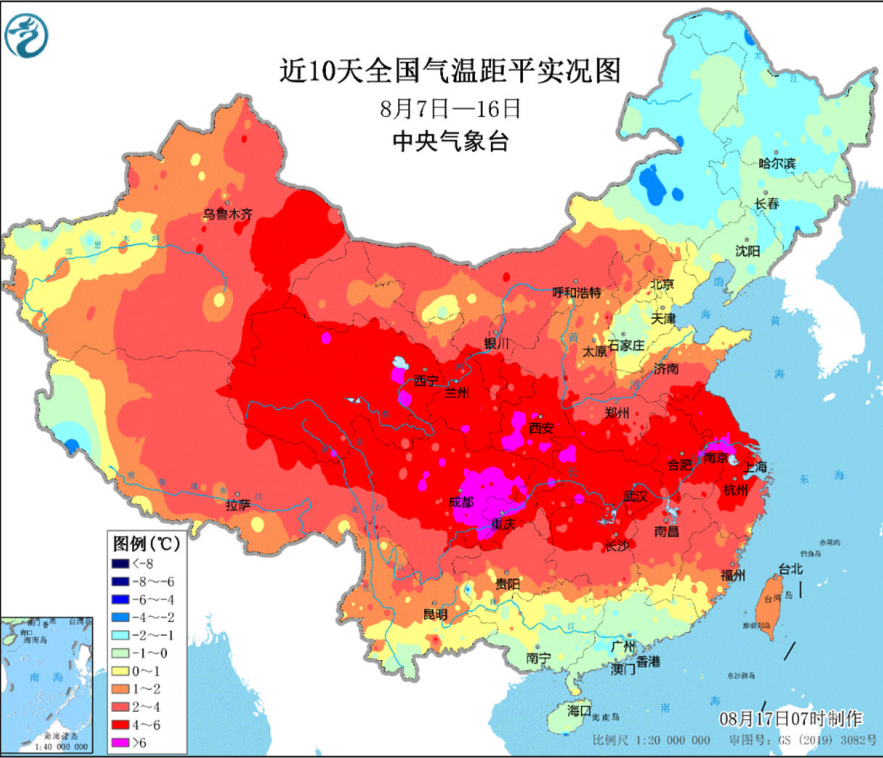

Below are two maps showing nationwide temperatures in the first two weeks of August. The first shows high temperatures above 30C (85F) across southeastern China, while the second shows temperatures as compared to the average of previous years. The red that covers much of central China is 4-6 degrees above the historical average, while the purple zone over Sichuan, including Chengdu and Chongqing, indicates temperatures that are 6 degrees higher the historical average.

One article titled “Turn off the filter and listen to the voices of Sichuan crying out” circulated widely on WeChat on August 23 before being banned. After describing the ways that popular media has turned drought and high temperatures into a spectacle or tourism event, the article narrated the deaths of two unnamed elderly men in rural Sichuan. The first, a 71 year old bachelor in the rural outskirts of Chengdu, suffered from heatstroke while working in his field on August 19. His body was found that evening, and the next day his relatives traveled to arrange his funeral, another 95 year old grandfather at home. When they returned, they found that the grandfather had also passed away. The funeral director they contacted told them that in the past several days, he had also been contacted by the relatives of five other elderly people who had passed away due to the heat––but that their deaths were not marked as being caused by this summer’s high temperatures.

Other reports emphasize the ways that power restrictions have spread beyond industrial production. Beyond “aesthetic” measures like reducing lighting in subways and on buildings or signage, power cuts restricted air conditioning in offices and commercial buildings. Importantly, newly introduced taxi fleets that use electric vehicles were rendered inoperable. Without air conditioning, sales of bulk ice by factories that were still capable of operating freezers skyrocketed, with large ice blocks being used by individuals or families as a way to keep cool. However, this is clearly a last-ditch effort available only to those who could purchase a quickly-melting block of ice. The same article noted that one hospital in Chengdu saw 13 heat stroke patients on the 16th of August, one of whom (a street cleaning sanitation worker) passed away.

Striking Food Delivery Worker Stabs Himself in Protest

A food delivery driver working in Taizhou stabbed himself three times in front of his workplace, after his boss refused to scrap a 1,000 yuan fine. Videos of the incident showed the man, who has so far been unnamed, lying in a pool of his own blood while ambulance workers tend to him. Witnesses told local media that the man came to the small delivery hub to tell his boss that he quit and demand payment of his remaining wages. The boss agreed, but insisted on enforcing a 1,000 yuan fine for going on strike. When the worker protested, the boss told him to take it up with the labor arbitration court (劳动仲裁), to which the man stabbed himself three times on the spot. The boss told local media in an interview that the man said he wanted to die right then and there. One commenter on a Weibo post about the incident said that the man had died of his injuries, though they offered no evidence, and we have so far seen no updates on the case.

The boss’s “suggestion” that the worker take him to court over the fine, is, essentially, the equivalent of telling the worker to “fuck off and die”, which is precisely what the worker attempted to do. Labor arbitration committees are lengthy, bureaucratic processes. Statistically speaking, workers have a higher success rate than employers, but very few workers with labor disputes have the time, energy or resources to see a lengthy legal case through to the end, considering the sums of money involved.

The incident occurred just before the two-year anniversary of the publication of “Delivery Workers, Trapped in the System” on September 8th, 2020 in Renwu magazine (whose translation we published here). The piece was widely read, and caused much public discussion in China and abroad about the arbitrary fines, long hours, and shit pay endured by food delivery workers. However, little if anything has changed for food delivery workers.

Forest Fires, Covid Tests and Volunteer Mobilization

The aforementioned drought and high temperatures led to a series of wildfires that broke out around Chongqing on August 23rd. Most fires were extinguished by the 28th, thanks to a significant mobilization of volunteer firefighters. Amid ongoing power cuts and wildfire smoke, the widespread covid testing has continued. The resulting images created two sets of viral images, with dramatically different political implications: On one hand, people shared video and pictures of long lines of urban residents waiting in line for covid tests created striking juxtapositions that went viral repeatedly, as in this video from Chongqing on the 23rd, with rolling smoke in the background of long lines for testing.

Other memes explicitly juxtaposed forest fires, covid testing lines, and (implicitly) power shortages, as the hashtag “The people of Sichuan and Chongqing want to cry” (#四川重庆人民要哭了#) went viral.

These two images from Chongqing circulated widely on WeChat. The first one shows wildfires in the top right juxtaposed against covid tests in the bottom left. Other instances, now lost to censorship or timeline algorithms, also pointed out how visible buildings lacked power. The second image shows testing staff in protective suits taking covid test samples from men who have been fighting the wildfire that is visible in the background.

Another set of images circulated in patriotic, “good vibes” articles like this one, which showcases “everyday people in the Chongqing wildfires”. While professional firefighters and soldiers were brought in to help fight fires, much of the necessary work was actually done by groups of autonomous volunteers who carried supplies in bucket brigades, cut firebreaks, and dug roads that provided access to burning areas. Although the author here points out that this process was extremely inefficient compared to the professionalized wildland firefighting of other countries, his perspective remains decidedly positive. Elsewhere, “spontaneous” responses to the fires were framed as expressions of Chinese indomitable will in the face of disaster. In particular, the willingness of youth to sacrifice was pointed out by articles such as this one, about motorcycle-riding volunteers who brought supplies up mountain trails to the frontlines of the firefighting effort. Other commentators, however, questioned faked DALL-E style imagery of “firefighting heroes” that was used in official news releases, including the previous link.

Fundraiser for a Worker with Silicosis

In 2019 we published an article and a translated rap song about a hundreds-strong network of workers who had contracted silicosis (also known as pneumoconiosis or black lung) while building Shenzhen in the 1990s-2000s—among the estimated six million people in China with the disease. The network sought to obtain medical treatment and compensation for the workers, and it became one of several main targets of the nationwide crackdown on leftists and labor activists following the Jasic Affair of 2018.

On August 20, the anti-authoritarian left WeChat blog East Wind Chiapas Power Drill (恰帕斯东风电钻) announced a fundraiser for a “fellow worker with silicosis” named Gu Fuxiang (谷伏祥), with whom the editor “had the good fortune to meet once,” to help cover the cost of his children’s tuition. Like the others in the 2019 network (to which it seems likely Gu also belonged), Mr. Gu migrated from his home in Hunan to work on construction sites in Shenzhen (including the Luohu Communist Party School and the Ping’an Finance Center, he notes), in this case as a drill operator from 2003 to 2012, where he contracted the disease due to lack of PPE. Now at age 56 the silicosis prevents him from working, so he relies on a meager state allowance of 1,400 yuan (203 USD) and his wife’s income from informal work to cover his medical bills and the household’s expenses—far from enough to afford the high school and college tuition and related costs for his son and daughter, amounting to 60,000 yuan per year. The post includes photos of Gu’s medical records and other documents to show this is not a scam.

In other countries this kind of fundraiser would seem to be the domain of church groups or reformist NGOs, but in China this topic is so sensitive that the platform had to disguise the character for “silicosis” (writing 尘肺 as “尘fei”) to decrease the risk of being shut down or worse. Several activists were imprisoned for a year and their organizations (including one that functioned mainly as a similar WeChat blog) disbanded due to their support for direct actions (repeated protests at government buildings) by a few hundred workers, so it is actually quite brave for this blog to take the risk of reposting Mr. Gu’s message. As the editor wrote, in verse format:

[…] Brother Gu, the fellow worker asking for help today

While himself sick with silicosis

Has worked hard to help other workers with silicosis

To seek out material and spiritual support for their lives

In today’s environment

This requires great courage and willpower

We hope not to see

One who has helped others then find himself without others to help him.

Recent English Publications

Cambodia and Myanmar Race to Become the Next Apparel Manufacturing Hub

“From October 2021 to March 2022, China lost around 5 percent of its textile export orders, 7 percent of its furniture and 2 percent of its mechanical and electrical export orders from the US to the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), especially Vietnam, according to US customs data…. Despite its low base, Cambodia’s export growth has accelerated and outperformed that of Vietnam so far this year. According to the country’s customs authority, Cambodia’s total trade volume reached $22.47 billion in the first five months of 2022, an increase of 19.7 percent from the same period last year. Total exports topped $9.41 billion, up 34.5 percent year-on-year. The top export goods were garments, leather goods and footwear.” (Caixin via Khmer Times, June 30)

China’s Surveillance State Hits Rare Resistance From Its Own Subjects

“Chinese artists have staged performances to highlight the ubiquity of surveillance cameras. Privacy activists have filed lawsuits against the collection of facial recognition data. Ordinary citizens and establishment intellectuals alike have pushed back against the abuse of Covid tracking apps by the authorities to curb protests. Internet users have shared tips on how to evade digital monitoring.” (NYT, July 14)

China’s Gen Z Is Dejected, Underemployed and Slowing the Economy

“A perfect storm of factors has propelled unemployment among 16- to 24-year-old urbanites to a record 19.3%, more than twice the comparable rate in the US. The government’s hardline coronavirus strategy has led to layoffs, while its regulatory crackdown on real estate and education companies has hit the private sector. At the same time, a record number of college and vocational school graduates—some 12 million—are entering the job market this summer. This highly educated cohort has intensified a mismatch between available roles and jobseekers’ expectations.” (Bloomberg, July 24)

Growing Up by the Sea in Qingdao

“Lost in the city where I grew up; lost at the oceanfront where I passed countless hours as a child. I realize, with a pang, that the sea of my childhood is forever gone, that the quiet and quaint coastal city I called home is no more. In its place another city of modern hubbub and skyscrapers is erected; a city separated from the tranquility and riches of the sea by too much commerce, too much traffic—a city in which I am a stranger.” (Weili Fan for Chinarrative, July 30)

New Labour Department Post Responsible for National Security and Monitoring Unions

“The Hong Kong Labour Department is slated to establish a new high-ranking post specifically responsible for national security functions, suggesting that henceforth the monitoring of trade unions will become more serious, being folded into the Department’s everyday work.” (HKLRM, August 4)

When the Water Runs Out: China’s Latest Power Crunch

“The main issues leading to the power insufficiency and power curbs are the extended heat wave and accompanying drought that has engulfed most of central and eastern China for over a month now. These hot temperatures have elevated power demand for cooling across the country, leading multiple provinces to record new historical highs for their peak power demand throughout July and August. Not only have the temperatures been hot, but they have been significantly hotter than in past summers, for a longer period of time. For Sichuan, this hotter-than-normal weather has been most pronounced over the past three weeks but goes all the way back to last month. Indeed, even back at the beginning of July, Sichuan was already facing tight supply for both peak power demand and daily power consumption, releasing policies to entice major industries to participate in peak-shaving via preferential power pricing schemes. The recent weeks have seen this extreme heat exaggerated to newfound heights, however, necessitating more decisive action.” (Lantau Group, August 22)

Heatwave in China is the most severe ever recorded in the world

“Low rainfall and record-breaking heat across much of China are having widespread impacts on people, industry and farming. River and reservoir levels have fallen, factories have shut because of electricity shortages and huge areas of crops have been damaged. The situation could have worldwide repercussions, causing further disruption to supply chains and exacerbating the global food crisis. People in large parts of China have been experiencing two months of extreme heat. Hundreds of places have reported temperatures of more than 40°C (104°F), and many records have been broken.” (New Scientist, August 23)

‘We Own It’: The Chinese Homeowners Squatting in Unfinished Buildings

“There is no running water or electricity, a single solar lamp providing the sole illumination. The only furniture consists of two single iron beds pushed against one wall, and an unpainted wooden board serving as a makeshift table. But the pair, who are both 60 years old, have resolved to put up with the basic conditions. They feel they have no other choice. […] Wang, Zhou, and nearly 100 other homeowners moved into the unfinished apartment compound — Jinling Apartment — just over three months ago. It was an act born of desperation and defiance.” (Sixth Tone, August 25)

Chengdu locks down 21.2 million people as Chinese cities battle Covid-19

“Residents of Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province, were ordered to stay home from 6 p.m. on Thursday, with households allowed to send one person per day to shop for necessities, the city government said in a statement. Chengdu, which reported 157 domestically transmitted infections on Wednesday, is the largest Chinese city to be locked down since Shanghai in April and May. It remained unclear whether the lockdown would be lifted after the mass testing ends on Sunday.” (CNBC, September 1)

Previous Monthly News Highlights

White Terror, Attacks on Women, Bank Protests, Falling Wages: News Highlights, May-June 2022

Struggling to Survive in Shanghai and Beyond: News Highlights, April 2022

Controlling the Soul’s Thirst for Freedom: News Highlights, March 2022

Chains of Patriarchy, Death from Overwork, Silenced Critics of War: News Highlights, February 2022

Drinking Algae, Folding Beijing, Fighting Lockdowns: News Highlights, January 2022

Fake Capital, Persecuted Speculators & Exploited Enterprises: News Highlights, December 2021

Notes

[i] In order to focus more on work for the third issue of our journal and a second book, we’ve decided to put these news posts on hold for a while. If you’d like to help us produce content for the next post, please contact us: chuangcn[at]riseup.net. (Header image: Dry riverbed of the Yangzi in Chongqing, August 2022. Photographer: VCG/Getty Images.)