This post is the fifth in a series of periodic1 summaries of highlights from Chinese-language news and social media, offering some analysis of economic trends and the changing character of class struggle in China. Through these posts, we hope to give English readers a broader sample of the discussions taking place across the linguistic and digital divide. In addition, we recommend a few recent English-language publications at the end. (If you notice mistakes or any important story that we missed, please contact as chuangcn@riseup.net and we can add it to next month’s post.)

Highlights from Chinese News and Social Media, April 2022

Life, Work, Resistance and Mutual Aid under Lockdown in Shanghai

This month we’re doing something different and focusing mainly on the lockdown in Shanghai, with only a few summaries of Chinese news and social media discussions about other topics, including some of the lockdowns in other cities. We’ve divided the Shanghai news into two sections: highlights here, followed by other news, and then another section with further Chinese sources about the Shanghai lockdown. (English sources are in their own section at the bottom.)

Week 1

Early compound organizing

“Finally seeing some hope” (看到一点希望)

This article from April 1 recounts the experience of a compound (小区) in Pudong whose residents organized a pact that they should all refuse to be transferred by state agents to quarantine facilities (方舱) in the event that one of them tested positive. Because the numbers of asymptomatic infections far outstripped those of symptomatic ones, with no deaths being officially acknowledged, compounds such as this one found it relatively easy to arrive at a certain level of consensus that formal quarantine was much more frightening than the disease itself. In this situation, the bottom-up initiative to effectively transition the compound itself into a quarantine facility is a demonstration of a widespread critique of lockdown policy. This article sparked attempts to emulate this kind of agreement, as well as other blog and media discussion – for example, the follow-up article “Shanghai Renheng Shore City’s people’s pandemic guide is too well-done, sparking the light of reason for humanity” (上海仁恒河滨城的民间防疫指南“太卷了”,人类的理性之光被点亮) provides analysis of the agreement and guide produced by the compound residents’ mutual aid network, and positions it as a potential way forward for Shanghai’s Covid-19 prevention policy. While this article did lead to widespread pushes against exiling or looking down on those who tested positive, the state still ultimately managed to send the vast majority of people who had tested positive to official quarantine sites.

Logistics breakdowns

“Trucking on the Yangtze River Delta under Covid: Stoppage, shortages, and unprecedented challenges” (疫情下的长三角公路货运:停摆、缺货和前所未有的挑战)

Several days into the lockdown of the eastern half of Shanghai, and on the first day of the citywide lockdown, difficulties with logistics were already becoming widely publicized. This article in the Economic Observer (经济观察报) describes “unprecedented challenges” to road-based trucking throughout the Yangtze River Delta, which amounts to over 70% of the logistics in the region: Local policies in individual districts or towns change daily, and drivers on the road anywhere in the region risk being forced to quarantine for 14 days, losing salary and potentially ruining cargo. Individual highway entrance and exit ramps are governed by local police, making it impossible to predict where or whether drivers will be able to get on or off the highway, and whether they will be able to make their delivery if they try to do so. Throughout the month, video of truckers stuck in one place on highways finding ways to feed themselves, such as these drivers who were able to fish and catch crabs while unable to leave Shanghai’s Chongming Island:

Restrictions on trucking are just one element in broad efforts to “harden” formerly invisible administrative borders. The following video, shared on Wechat on March 31, claims to show a hastily-erected fence (complete with a searchlight-mounted guard tower) on the administrative border between Shanghai and Taicang, Jiangsu, which are normally linked by subway lines.

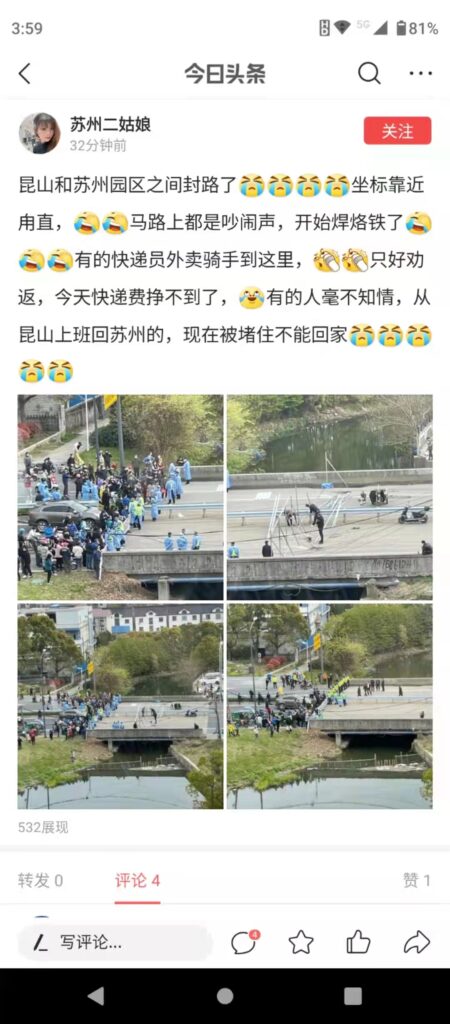

Elsewhere, roads linking the Yangtze River Delta cities of Suzhou and Kunshan were blocked off, cutting off delivery from one side of the formerly open boundary to the other.

People in Suzhou reported that security guards were tasked with checking the trunks of cars entering and exiting communities, supposedly to check for “illegal border crossing” (偷渡) out of Shanghai and Taicang (where covid cases were also reported in early April).

Makeshift boundary fences were also reported in other parts of China, such as Xi’an, where this video was taken of people sneaking under the wall separating that metropolis from the smaller city of Xianyang during an early April rise in cases there.

CDC Official Breaks Rank in Phone Call with Concerned Civilian, Recording Goes Viral

The recording of a 20-minute phone call went viral on April 2, documenting the words of a local CDC official responding to the son of an elderly Shanghai couple, who had received positive test results while in quarantine, as the close contacts of another positive case had been announced publicly. The official, an epidemiologist named Dr. Zhu Weiping from the Pudong District Pandemic Control Center (a branch of Shanghai’s CDC), tells the man that all the test results on Alibaba’s “Health Cloud” are displayed as negative, even when a result is actually positive. She also suggests that the patients could refuse to go to centralized quarantine if they are not shown a certification indicating a positive result. Dr. Zhu expresses frustration and anger about the lack of effective medical facilities, and about the inept leadership both at the city level (where positive test results were not recorded in an efficient or transparent system) and at the central level, where pushes for universal centralized quarantine had originated.2

The call set off widespread anger and discussion online, with many supporting the CDC official for her frank statements about the poorly-managed testing and quarantine system, and her advice to the caller to require that the team transporting his parents show a paper certificate verifying the positive test results, which many commenters took up as a means to avoid being sent to quarantine. The use of this kind of language is evident from a second audio recording that went viral eight days later (on April 10), when a woman, who had been told she had tested positive, refuses to open the door of her apartment to the team assigned to transport her to a quarantine facility unless they provide a physical report verifying that she did in fact test positive. Notably, she is eventually forced to accept transportation despite her protests.

At the same time, others noted that the CDC official had recognized that the quarantine policy was in many cases more harmful than the outcomes of Covid infection, and that policy emanating from the central government was overruling Shanghai’s theoretically more-humane local policy. Similar outlooks were expressed in articles such as “This female official [sic] brought back Shanghai’s lost respect” (这个女官员为上海找回了失去的尊严). It is also notable that the official was widely described as a “whistleblower” (吹哨人) who exposed the reality of the city’s dire situation, despite the fact that she hadn’t initially agreed to be recorded. Following the call’s viral circulation, online commenters called to “protect Zhu Weiping,” and the Shanghai CDC circulated a notice warning staff not to share personal opinions:

A few days later, an article quoting Shanghai health professionals continued to shore up the idea that pandemic restrictions might be worse than the disease itself: “Shanghai frontline doctor: The fact that the lockdowns may have caused more deaths than the virus is already common knowledge among doctors” (上海一線抗疫醫生:因封控去世的患者可能比病毒致死的更多,已是醫生共識)

Food and household registration

Beginning in late March, when purchasing food for delivery became largely impossible, food packages put together by local residents’ committees were often the only sources of fresh food available throughout the city. For example, this video from March 31 shows migrants complaining that food is being denied to them (the woman recording notes that the food is likely produced in Anhui, where she and other migrants are from). “When they take statistics, they keep asking everything, they’re very careful. But when they’re sending food out, it’s not that careful at all.” A second clip cut expresses a similar sentiment: “They only send food to Shanghainese, we outsiders don’t get fed at all.”

Other videos circulated on Weibo, such as this one labeled “Food aid: You live here, but do you havehousehold registration (hukou) here?” (“援助的蔬菜: 你是居住在这里,但你户口在这里吗?). Restrictions that prevented migrant workers from receiving government food packages may have also been behind instances such as this seizure and redistribution of food being transported on a truck on the outskirts of Shanghai.

The first video here, posted April 6, shows another similar instance. In the second half of the video, a volunteer dressed in PPE who is herself a migrant without Shanghai hukou breaks down when she realizes that food deliveries will be denied to fellow migrants.

Kids in centralized quarantine facilities

On April 2nd, images and video of children in centralized quarantine facilities began circulating, with reports that children who tested positive were often separated from caretakers. The Twitter thread linked here also provides contextualizing screenshots from Weibo:

The South China Morning Post reports that this policy was eased by April 5th.

Repression & growing anger

A drone broadcasting “Please comply with covid restrictions. Control your soul’s desire for freedom. Do not open the window or sing” in response to people protesting lack of food.

Viral outrage over a video of a corgi being beaten to death by quarantine enforcement personnel leads to pet owners’ increased worries about being sent to centralized quarantine — this is just one of countless records of pets being beaten to death for dubious reasons in multiple cities over the past two years (狗狗的命就不是命了吗?)

A residents’ committee attempted to organize residents to yell “We’re grateful to the government” (感恩居委会) at a certain time, but instead everyone chants “You stupid cunts in the residential committee” (傻逼居委会) from their windows

Dialysis patients denied access to hospital resources on April 2:

Week 2

Neighborhood organizing: Down with the residents’ committee!

As the lowest level of government, neighborhood residents’ committees (居委会) are mostly run by party members who often do not live in the compound where the committee itself is based (often one or two rooms in a ground-floor unit of a residential complex). The committee itself is relatively poorly-funded and not heavily staffed, and membership is normally a part-time position dedicated to things like resolving disputes between neighbors. During lockdown, however, residents’ committee members have been required to live in the committee space itself in order to serve and govern the communities they are assigned to. In older communities in the western half of Shanghai, this often means that a resident committee of 10 people is theoretically responsible to meet the needs of 1,000 or so residents, while in large-scale commercial developments in the eastern half of the city, the residents’ committee is often even more understaffed. When it became clear that the lockdown would not end quickly, some understaffed residents’ committee members resigned en masse, as was the case in Changli Garden in eastern Shanghai, where eight committee members were asked to provide support for 4,000 residents. In an open letter dated April 7, the secretary of the committee described the lack of support and confusion he and his colleagues had been dealing with, including forcing residents to wait for twelve or fourteen hours in the cold prior to being picked up for transport to quarantine facilities.

Elsewhere, residents took matters into their own hands, and removed the formal committee in favor of self-organized alternatives. One day prior to the Changli Garden committee’s resignation, residents of one compound in Putuo, Anju Chaoyangyuan, kicked out the formal residents’ committee and committed to self-organized distribution of resources. Residents had been unhappy with the inefficient distribution of resources by the committee, and kicked them out of the compound in order to organize distribution by themselves:

A post they shared, “The pandemic is ruthless, but Anju has heart” (疫情无情,安居有情) describes how the group organized distribution of collectively purchased (团购) goods and volunteering to distribute Covid self-tests through Wechat. Another internal announcement (安居朝阳园封闭管控期间居民常见问题Q&A) shows the kind of information shared between residents: Hotline phone numbers, the difference between “closed” (封控) and “controlled” (管控) buildings where cases had been identified, and ways to get medication when delivery is unavailable. While the group was unable to take over key bureaucratic functions, such as issuing passes that would have allowed residents to go to hospitals during an emergency, their alternative structure is notably more transparent than that provided by most formal residents’ committees.

Protests

April 9 saw the first large-scale protests of the lockdown month, including clashes with police, and fighting over the distribution of supplies, mainly in Shanghai’s Songjiang District:

Elsewhere, people surrounded a cop car and demanded the release of someone who’d been arrested inside. Details unclear, but the poster noted that covid restrictions have caused more resistance than the average social unrest, such as the forced demolition of homes

Cries for help

On April 9, an essay by “stormzhang” went viral on Wechat (archived here: 求救!!!, also available with an English machine translation: “Help!!!”). The essay provides a relatively comprehensive overview of the pandemic in early April, with a particular focus on the difficulties of accessing food. The essay emphasizes that, while the portion of the population facing acute food shortage might be relatively low, the absolute number of people going hungry in a city of 25 million people was likely quite large, so there was an urgent need to create structures that would allow for effective food distribution.

A handwritten letter from Anhui migrant workers in Shanghai went viral on Sina Weibo, pleading for help and supplies (安徽在沪农民工求助,帮帮他们!)

Another first-hand account with photos of a septuagenarian woman with non-covid-related medical conditions describes unsanitary conditions in Shanghai quarantine facilities (100 people sharing 2 toilets that never get cleaned, etc). Begging for help, she asked her son to post this account on Weibo.

Notable quotation: “年轻的点长你怎么能这样对待我这样一位一辈子安分守己的老太?我年轻时一贯听党话勤勤恳恳任劳任怨工作,为我国的石油事业贡献自己的一切,现在老了没有用了就可以不管我的死活了?”

Week 3

More Protests as Hundreds Relocated to Make Way for Quarantine Facility

On April 14, about 500 residents of the Zhangjiang Nashi residential community in Pudong were evicted in order to allow the entire residential community to be used as a quarantine facility. Claimed as the “first rental-only development in China,” the community was not fully occupied, and several empty buildings were first used as quarantine facilities before the remaining residents were evicted. The eviction itself led to police brawling with residents who refused to leave, with photos and videos spreading rapidly on WeChat. The event was summarized in English on WhatsonWeibo.

On the same day, residents of an upscale compound in Zhangjiang Town several kilometers away staged street protests against the establishment of a quarantine site in the elementary school next to their compound, worrying that they would be infected by individuals brought to the neighborhood to quarantine. Here residents march shouting “Keep the quarantine site out of the school!”

The protest was quickly broken up by police. Here, the person recording notes “I never thought I would hear the national anthem in this kind of situation” while police were pushing protesters back.

A woman with a megaphone describes her grievances, framing the protest around residents’ willingness to cooperate with hard lockdowns

Eventually, police pushed in to break up the protest. The woman in the second video states, “We saw violent clashes on the scene. SWAT police have already gotten involved. The cops at the front, the leaders, were really fierce, pushing us around and taking our stuff. I was pushed around too.”

Online Resources for Mutual Aid

List of websites set up by actual grassroots volunteers helping people to survive during the lockdown.

These and the examples summarized above (and in this English report) are reminiscent of those set up by mutual aid networks in Wuhan and elsewhere in early 2020, when the Chinese state was still, first, denying the existence and nature of COVID, and later, basically just enforcing the lockdown without doing much to ensure that people could survive. Only later did the state recuperate those mutual aid networks it could control, and force those it couldn’t to shut down (as documented in our book Social Contagion and Other Materials on Microbiological Class War in China). We hope other observers and participants can help to document the mutual aid and class struggle still unfolding in the Shanghai Lockdown of 2022.

Disturbing Posts Go Viral around April 22, Despite Aggressive Censorship

First, this captioned photo was widely reposted before and after being blocked by mainland platforms, summing up in one image the fate of delivery workers, and many others, in the midst of this lockdown officially meant to protect human lives: “A delivery worker had a traffic accident, injured his head. The police came, his family came, but not the ambulance which finally arrived hrs after & only to declare his death. The rain fell on his blood.” (一直以来被封在家,今天切实体会了上海医疗的瘫痪。就在刚刚,外卖小哥发生车祸,头部受伤,一地的血,距离拨打120已经1个小时了,120没来,警察来了,家属来了,120依旧没来…)

Then there was a podcast interview with guests in a Shanghai quarantine facility, “I See a Desert Island of Elderly People Begging for Help” (我在方舱,看见老人们的孤岛求生), about their abusive treatment there. The interview got 300,000 hits in the first 2 hours before being blocked on Chinese media, but is still available on the host’s blog, hosted outside the Great Firewall, where it received 10 million visits within the first 24 hours. A transcript of the interview is available on CDT.

In addition to those posts and the more famous video “Voices of April” (whose original post received 5 million views before being taken down), don’t miss the more entertaining, yet arguably more damning, video “Late Spring in Shanghai” (上海晚春), which also went viral despite censorship around the same time. It opens with the now infamous televised call by a local official to “control the soul’s thirst for freedom” before launching into montage to the tune of “Cheer Up London” by the Slaves.

Rapping inside and against the Lockdown

Two rap videos critical of the lockdown in Shanghai dropped this month. At least one, “New Slave” (新奴隸) by Shanghai-based rapper 方略 Astro (新奴隸), went viral around April 18 before being censored from mainland platforms. Listen to the video of the artist rapping in Mandarin from inside his locked down apartment (with Chinese subtitles), here:

A second video, “Free” by Sean Zhang, was released a few days later on April 23, but as far as we know this was never widely posted on mainland platforms. The lyrics are less interesting then the first, but some of them are in English, with subtitles in both languages, so may be more digestible for English listeners:

Week 4

Hundreds of Delivery Workers Still Forced to Sleep on the Streets

In addition to many other reports and posts about delivery workers that have circulated in the past month (a few examples summarized above), on April 27 Caixin published a report, “Many delivery drivers are still sleeping on the streets of Shanghai” (仍有不少送货骑手露宿上海街头). According to the report, “Hundreds of delivery drivers are living on the streets of Shanghai, some forced to brave torrential rain and strong winds in cardboard boxes.”

Left Analysis of the Lockdowns

This month has seen the publication of a number of Chinese left (generally Maoist) critiques of both the way the state has implemented the lockdowns as well as liberal perspectives on the issue. So far all we’ve seen has been quite far from our own perspective, but we highlight these in order to give readers some idea of what’s being discussed publicly from left perspectives on the tightly censored Chinese internet.3 Here are three popular examples:

“Three Angry Suggestions to the Shanghai Government against Bureaucratism” (上海基层愤书抗疫三建议,呼吁反对官僚主义) by Chiapas East Wind Power Drill (恰帕斯东风电钻), published April 2. Among other things, the article suggests that the CDC and local government should collect info where delivery workers and others could be subject to serious living or working conditions, and “volunteers,” if they can, should publish records and maps to help workers help each other directly. It also proposes that local governments, the real cause for food deliverers’ misery in this pandemic, should force more hotels to open free rooms for migrant workers to stay.

“What Must be Understood and Fought (regarding the pandemic in Jilin)” (【吉林疫情】眼下必须了解的,和必须争取的) by Jixiangma (吉祥犸) for the Khazar Society (哈轧尔学会), published April 8. This article advocates learning from the wisdom of China’s old socialist work-unit (danwei) system to help quell “fragmented bureaucraticism and professionalism,” as if a total, well-organised system of bureaucrats would be the key to dealing with this pandemic.

“In My Next Life I Won’t Be an ‘Excellent Student’: Shanghai” (上海:再世不做“优等生”) by Haishangcao (海上草), also for the Khazar Society (哈轧尔学会), published April 30 (then censored from WeChat the next day after widespread reposting). This article traces the change of local attitudes to “flexible control” (from pride to disdain), and remind us of some comments outside Shanghai that bureacrats there were consciously acting in a laissez-faire way. However, both attitudes suggest an assumption that Shanghai is supposed to act better against pandemic since it is one of the leaders among first-tier cities, while in fact the city relies on a network of Internet retail business and outsourcing from local administration. Unravel this parable of “open city” and we will see how the surplus value of “migrants” and “outsiders” are exploited by local urbanites.

In Other News…

Annual Survey of Migrant Workers

This year’s official nationwide survey of migrant workers was published on 29 April. The report, titled the “2021 Migrant Worker Survey”, is released every year at the end of April and cites data for the previous compiled in the previous year.

There were few striking results – like many government surveys and statistical releases – but a few points are worth highlighting briefly. But first, a word about the subject of the report: the term “migrant worker” by definition simply means a person with a rural household registration (户口 hukou) that works in either non-agricultural industries locally, or works outside their rural registered area for more than six months out of the year. Between ten to twenty years ago, the term became associated with young rural persons who came to coastal industrial hubs to work in factories, though the definition is becoming increasingly antiquated as the demographics, industrial structure, and cultural identities of workers continue to change.

For example, in the average age of the migrant worker has steadily increased over the years. This year, the average age of a migrant worker was 41.7 years old, while a decade ago the average age was just 36 years old, according to the 2011 report. To make the contrast more clear, today 27.3 percent of migrant workers are over 50 years old, compared to just 14.3 percent a decade ago.

The overall number of migrant workers sat at 292,510,000 in 2021. The number has grown steadily in recent years, except for in 2020 when the number of migrant workers contracted slightly during the first year of the pandemic.

In terms of industry, just over half of migrant workers were in “third tier” service work in 2021, though this number feel slightly, by 0.6 percent, over 2020. The number in manufacturing feel by 0.2 percent over the previous year to 27.1 percent, compared to 36.0 percent in 2011. The drop in service work over the previous year was matched by a 0.7 percent growth in construction work to 19.0 percent.

Pay jumped up in 2021 by 8.8 percent to 4432 yuan per month (approx $670 USD), after slow growth in 2020. Wages were the highest in manufacturing, which also saw the fasted wage growth. Pay was generally far lower, and wage growth slower, in service sector jobs like food service.

Sometimes the statistics say more through things that are omitted. Years ago, reports included statistics on working hours, and what percent of worker had signed a contract with their employers. However, many of these were dropped over time, likely for the embarrassing trends in their results. This year’s report omitted a section on migrant worker satisfaction in cities, which was present in last year’s report.

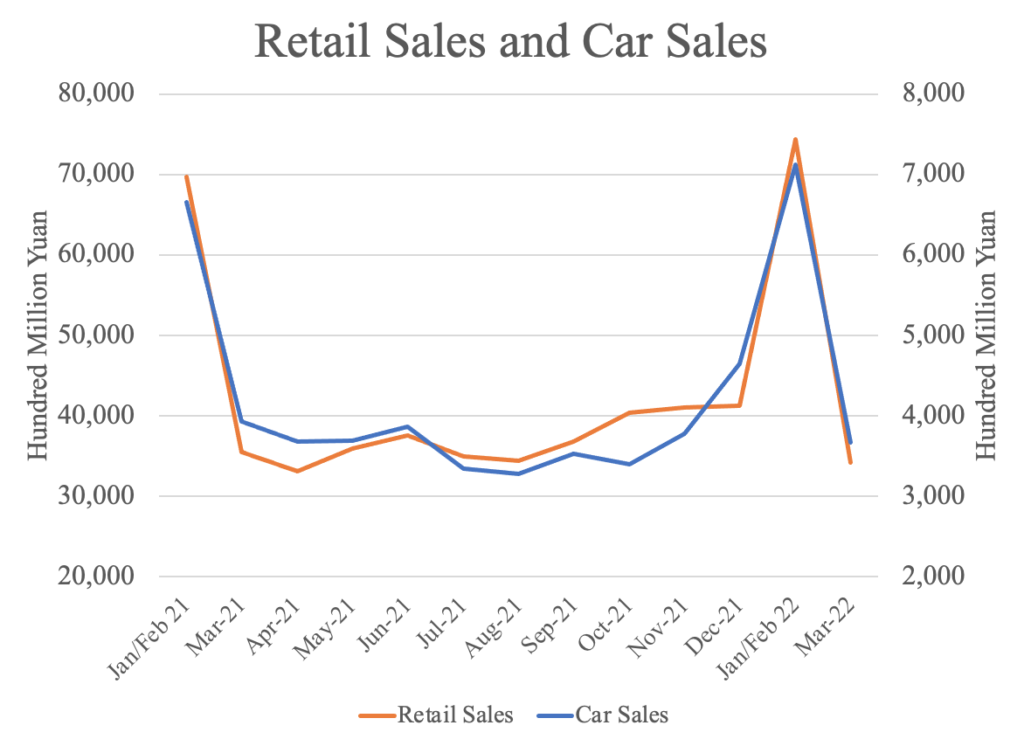

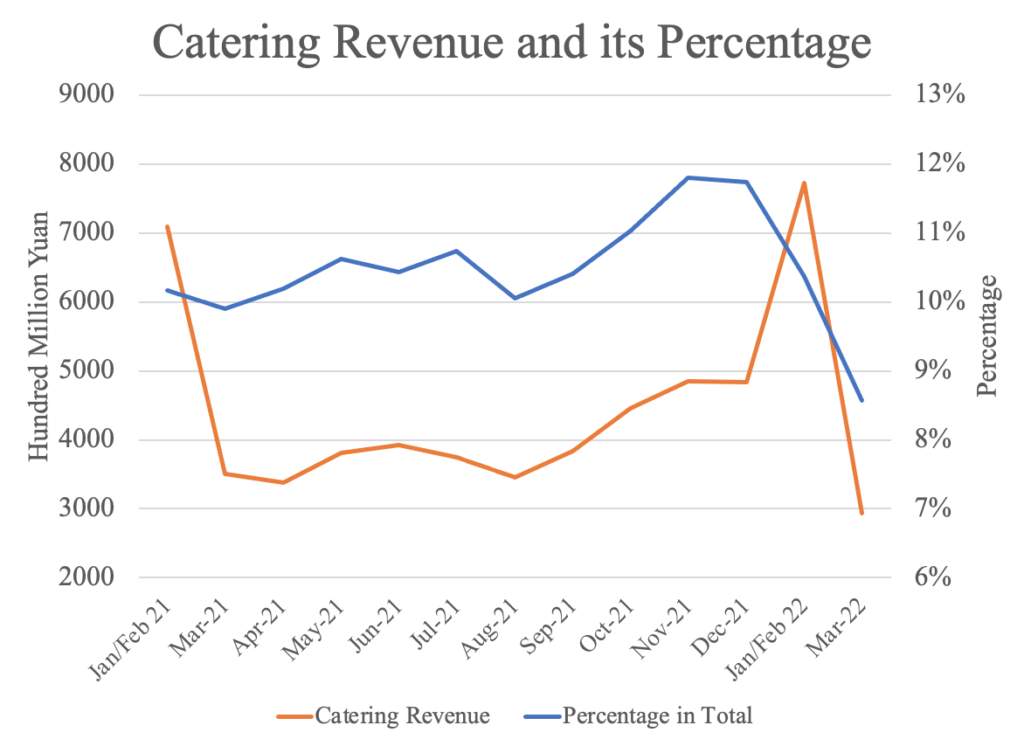

Q1 Data on Retail and Consumption

There are some anomalies in the latest release of consuming and retail sales data (2022年一季度社会消费品零售总额增长3.3% )

First, the whole retail sales in March recorded a surprising plummet of 3.5% YoY, and car sales a similar fall of 3.0% YoY. Car consumption has been a stable driver for retail sales with a stable percentage of 9-10% in total, so it should give us a glimpse of the general willing to spend money in China society.

Second is catering revenue (referring to restaurant and foodservice businesses) which recorded a sharp decline both in absolute volume (-16.4% YoY) and its percentage in total retail sales (less than 9%). This reflected the impact of frequent lockdowns in various cities when people could rarely if ever go out for meals.

“Relay Loans”

While China’s economy continues to show clearly downward trends, the focus on real estate along with the concern of missing another chance to make a fortune has never faded. On April 7, some banks in Guangdong secretly relaunched a “relay loan” (恒丰银行推“接力贷”:父母还不完房贷,子女来还!) where children are responsible for repaying loans when parents default. Despite this scheme being stopped by regulators in less than a day (“接力贷”又“死灰复燃”了 “一日游”后被叫停), we should expect more such experiments from local governments to “support the economy at all costs.”

Housing Market, Crackdown or Not?

Although radical housing loans like above were stopped, that does not mean the central state has been unanimous to quash the industry. In fact, after President Xi demanded that China’s growth outpace US this year, bureaucrats were desperate to find a leeway in a dilemma. On one hand US is about to raise the interest rate, thus attracting capital inflows and destabilizing China’s market, so it cannot keep the interest rate too low; on the other hand, China’s economy has been in such a pessimistic state that the market calls for more accommodation, which means more liquidity and lower interest rate.

That is why the vice-premier Liu He supported local governments to ease housing policies’ restriction, and why a government adviser claimed that “continued weakening of the industry may cause bad debts to spike and the entire financial sector to go under”. But this argument met a challenge from Liu’s peers, another two vice-premiers Han Zheng and Hu Chunhua, whose supporters argued that China’s banking system was resilient to this industry’s downtrend. So far there has not been any clear settlement for this difference.

Laws of Nature

After one famous economist had advised workers against wasting time on commuting last December, on March 30 another economist uttered a similarly out-of-touch comment that young people’s inability to afford to purchase homes is a “Heavenly Principle”4(董藩:年轻人买不起大房子是天理!想问问这到底是什么意思?). In fact his perspective on wealth was already highlighted back in 2011, when he asserted that those who could not accumulate 40 million yuan by the time they had reach 40 years of age should not be his students. “For those with higher education, poverty means disgrace and failure”.

Actual Prison

While tens of millions in Shanghai, Jilin, Ruili and other cities have been forced to live under conditions similar to house arrest (under lockdown at home) or prison (in dismal and sometimes unsanitary quarantine facilities), a detailed description of life in an actual Chinese prison also went viral this month – in response to a post on Zhihu (similar to Quora) titled “I’m about to go to prison, is there anything I need to be prepared for?” (马上就要去坐牢了,有什么注意事项嘛? 5). Most of the details were just as you would expect: a strict hierarchy for new and old prisoners; be obedient to the wardens and you’ll be treated nicely or even get early parole; no smoking for some prisons, depending on what lengths you’re willing to go to. But what we found particularly interesting was how Chinese prisons (like those in the US and many other countries in the global republic of capital) seem to function like a production unit:

First, wardens worked in shifts of “14+14,” that is, 14 days working in the prison and 14 for quarantine outside. Wardens took up different responsibilities such as “production” and “mindset transformation,” and barely cared for others. For them life was more boring, so they could play chess with the prisoners sometimes. Second, new inmates are likely to be assigned low-paid jobs sewing garments such as underwear, uniforms, and PPE such as hazmat suits. The pandemic’s impact on the economy has decreased the number of production orders sent to this facility, so some prisoners only worked two days a week.

Prisoners with higher levels of education get the privilege of assignment to less physically exhausting jobs such as bookkeeping, writing reports, quality control, and equipment repair. They also have better chances of obtaining early parole.

IP Addresses Reveal Locations of Nationalist Platforms

This April Wechat, Douyin, Weibo and other social platforms began publicly displaying users’ location for all users according to their active IP addresses. The official reason according to Weibo is to reduce “malicious rumors” by people claiming they were present or victims where accidents happened. Ironically, this policy exposed more about those harmless accounts than malicious ones. Some celebrated Weibo accounts that were supposed to be abroad, like HereInUK (英国那些事儿) focusing on funny and popular news in the UK, turned out to be operating from China. Also accounts about local affairs were exposed to be operated in other cities or provinces.

On the other hand, some accounts famous for nationalist and patriotic stances were exposed to be operating abroad. Imperial Bar (帝吧), which once went viral for trolling the comment sections of “anti-China” accounts, showed their IP address to be based in Taiwan. Another account Lianyue (连岳), whose theme was to criticize the US and Japan, tried to defend why his IP was in Japan by claiming he was just seeing a doctor there. “I am a Chinese, live or dead.”

Apparently out of embarrassment, Weibo changed this policy after one day. Right now accounts of popular stars, online celebrities, enterprises and the government seem to be exempted, although there is really no transparent criterion for it. Netizens left sarcastic comments for this:

LMAO seeing the account about France was in Shaanxi.

This is a campaign of daylighting. Those high-standing are now completely exposed to be losers lying under the flag of patriotism.

Can they show the IP of prisons? [it is said that some trolling comments were in fact operated by prisoners]

Lockdowns in Other Cities

April 6 – “JD County,” Heilongjiang

“Pandemic-control doctor commits suicide out of shame” (抗疫医生时军,不堪受辱自杀了!):

A report on the suicide of a doctor in Heilongjiang, who treated a patient who had faked a PCR test result. The patient eventually turned out to be spreading covid, and was likely the origin of an outbreak that shut down the county, with high costs. The doctor was interrogated for a week, and also sent to a medical examination while handcuffed. The blog claims that the shame of this experience led him to commit suicide while still in detention.

April 7 – Haining, Zhejiang

This rather iconic image is said to come from Haining, Zhejiang province, and speaks for itself. A poor old man, literally beneath the boot of the state. Some say the man in the picture is the “uncooperative super-spreader beggar” wandering the streets, labelled as “patient zero” who allegedly brought the virus to Haining, according to state media.

April 8 – Changchun, Jilin

Some of what we’ve seen, like this photo here, is of unclear origin, but it is a pretty clear expression of what is going on the ground. The graffiti here reads something like “zero covid my ass”. Might be from Jilin, or somewhere in the dry northeast, rather than green Shanghai

In Jilin, police bark via megaphone at a resident who issued “inappropriate” remarks in a group chat, and asked them to “fix” what they said, and say their remarks amount to crimes. They call them by their house number from the street, for all to hear

April 24 – Beijing

Beijingers hoarding food in spite of official guarantee food is adequate

https://web.archive.org/web/20220424152822/https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/gs6W5X2aOfWLUnyE7b-Hjw

By the end of April, parts of Beijing were under lockdown, and by early May, it appeared that hard lockdown for the entire city along the lines of Shanghai might be in store.

April 28 – Trend toward locking cities down after a single case of COVID?

While central government officials continue to repeat that the “dynamic” zero-covid policy is necessary, as China’s health care resources would otherwise run out quickly, local governments have tended to declare partial or nearly total lockdowns as soon as a single case is confirmed, in fear of further contagion. Some commentators, such as the author of the April 28 article “Shutting Cities Down after One Case: As Local Pandemic-Control Policies Take a Sudden Turn, What Should We Do?” (一例就“封城”!各地防疫政策突然掉头,未来到底该何去何从?), have interpreted this extreme response with a sort of knowing voice: since the zero policy is too strictly controlled from above, lower-level officials need to cut off any suspicious cases as fast as they can, to minimize the effect on the economy––that is, as long as potential economic growth after lockdown can surpass its costs.

Further Chinese Sources on the Shanghai Lockdown in April

April 3

How one woman lived in a convenience store for 23 days: 我一个人,在上海便利店住了23天.

Pandemic control personnel (called “volunteers”6) pushing into someone’s house, supposedly to check the number of residents:

April 5

An older “volunteer” (pandemic control personnel) was reported as having been beaten to death after attempting to restrain someone from moving around in their residential compound – video purports to show other volunteers performing CPR on a figure lying on the ground, while images show a group chat saying “someone just got beaten” and a notification of having filed suit against someone for homicide.

A record of quarantine life in hospitals of Guangzhou and Shanghai over the course of three months: 我在中国三个月的魔幻之旅.

April 16

Shanghai’s human resources authority recruits delivery workers from other cities to for “one-way” trips into the city to provide delivery services while most of the city’s delivery workforce remains locked down and unable to work. Commenters refer to these as “suicide missions”, given the likelihood that once delivery riders arrive, they will eventually test positive and enter quarantine facilities. By April 14, the city human resources department was offering ¥1400 to each rider who was willing to make the trip to Shanghai. (上海保供配送骑手招募中)

One woman’s experience crossing the Huangpu River several times over the course of two days as she worked to help her elderly parents obtain medical care were detailed in a Wechat post: Sneaking out of her compound after midnight, riding a shared bike for dozens of kilometers, and bribing the driver of a fresh vegetable delivery truck to pass police checkpoints, and eventually riding a shared bike directly through a tunnel under the river that divides the two halves of the city. (午夜狂奔:一个普通人的渡江侦察记)

April 27

A WeChat blog interviewed 10 university students about their experiences during lockdown on campus (被封在宿舍的大学生如何度过每一天?). Some in Shanghai said that they had to rely on hearsay because there wasn’t any official notice for the followup of lockdown. “I had a weak sense of time in the end, because every day felt the same… I didn’t have anything to hope for in my mind.” Some had to barter food and kept speaking of happy things to light up the spirit: “We wouldn’t starve to death but couldn’t have a full stomach either”. In Jilin things seemed a bit better. Students left thank-you notes on the doors of “volunteers.” Some said they ran out of leisure means and had to take up their minds to face reality and study.

May 1

Heart-wrenching video of a worker in Shanghai, who stops a truck to expose his desperation and hunger.

The man breaks down crying when given bananas and crackers. He says, “Shanghai people, not one person cares about us. Take care of us! Expose this! Help me expose this! I am a worker. I’m going to starve to death!” The truck appears to have two passengers, what sounds like a man and a woman. At first they are confused, don’t understand him, and tell him to get out of the way. The man filming in the truck says “bye-bye” as they begin to drive past, but the truck then stops. The female voice talks with the man, and she understands he’s hungry. They give him some crackers and bananas, and he breaks down crying, saying “thank you. thank you.” A Weibo post of this video went viral, with lots of concern, discussion and investigation in the comments. Video of desperate worker posted, coincidentally, on May 1: International Workers Day.

The quote used above comes from the top-rated comment on the thread. Lots of other good info came up in the comments. Sleuths in the comment section pinpointed the location to 3879 Huqingping Highway, out in the Qingpu district of western Shanghai. Most people in the comments agree that the man has what sounds like a Shandong accent. One person says his dialect sounds like the area at the intersection between Henan, Shandong, Anhui and Jiangsu provinces. It’s unclear what the drivers in this red truck are doing, but we can guess. It appears the man filming is in white coveralls worn by the “health workers” operating epidemic control. Many of the white clad workers are migrant laborers recruited from all over the country. In the video, across the road we can see another red truck, a flatbed with drivers in white. We might guess that both trucks are health workers of carrying supplies, and the man stopped the nearest people working in an official capacity of some kind. There’s a lot we can’t say for sure. But we can say that he is for sure not the only starving, upset worker in Shanghai, or elsewhere in China, as the government’s crippling control measures test human capacity to bear them.7

Recent English Publications

A letter from China: on the lockdown, with brutality and powerlessness against COVID

“Why isn’t there more trouble in Shanghai? When I discuss this question with my anarchist friends here, all they can think of is that Chinese society is blatantly atomised. It is precisely this isolation, powerlessness and lack of empathy that make their political practice in China so difficult. The big waves of strikes were a long time ago. A friend says he deliberately devotes little time to the events in Shanghai because he finds it unbearable. Afterwards, I have the impression that I am only now grasping the social challenge that my friends are facing all the time.” (Wildcat via Angry Workers, May 3)

The Legacy of the Uyghur Rock Icon Ekhmetjan

“People still remember where they were the day Ekhmetjan died. It was Thursday, June 13, 1991. He was only 22 years old.” (Art of Life in Chinese Central Asia, March 27)

China’s zero-Covid policy risks causing agricultural crisis and food shortages

“According to official data, as many as a third of farmers in northeastern Jilin, Liaoning, and Heilongjiang provinces have insufficient agricultural inputs after authorities sealed off villages to fight the pandemic. The three provinces acccount for more than 20 percent of China’s grain production.” (FT, April 5, paywalled)

A voice from old Shanghai under COVID lockdown

“On April 4 and 5, 2022, as Shanghai’s strict lockdown intensified, leaving many residents with no food in their fridges and forbidden from leaving their apartments, a short video titled “An Older Shanghai Man Vents His Fury” (上海老人家发怒) circulated widely on WeChat. The video showed a man outside an apartment building giving health workers in hazmat suits a piece of his mind. The popularity of this monologue of frustration hinted at how much, and how little, can be aired in China’s most globalized metropolis” (Supchina April 6)

Shanghai lockdown ‘will have a global effect on almost every trade’

“A spate of lockdowns in Shanghai and other Chinese cities is piling severe pressure on transport and logistics across the country, exacerbating the economic fallout of the government’s commitment to its zero-Covid policies as cases continue to soar to record levels” (FT, April 7, paywalled)

The Qualms and Queries of Locked-Down Shanghai Residents

“Sixth Tone’s sister publication, The Paper, launched a helpline platform on March 24 to collect local residents’ requests for help and connect them with relevant government departments and neighborhood committees. It has since received over 2,000 requests, of which 85 have been made public. Those 85 requests made between March 25 and April 4 showed most respondents seeked various medical assistance, while others were concerned about daily food supplies. Nearly half of all the issues faced by the respondents were resolved.” (Sixth Tone, April 7)

Shanghai Doctor Speaks Out Against China’s Covid Policy, Strikes a Nerve With Weary Public

“Until Saturday, Dr. Zhu Weiping was a little-known epidemiologist working for Shanghai’s Pudong district. That was when two recordings in which she shared blunt criticism against the city’s Covid-19 policies went viral and she became a beacon for many fed-up residents.” (Wall Street Journal, April 7)

My experience in the Fangcang-Hospital

Detailed first-hand English account of life in a quarantine facility, with photos: “Give up living as a human. Accept being an animal or livestock…” (LeonaCheng, April 9)

Migrant workers in China find new jobs — and precarious conditions — in COVID control

Interviews with the precarious migrant workers now staffing the army of pandemic-control “volunteers”: “the economic downturn and more regulations mean many of those sectors are shrinking. As a result, labor agencies are pivoting and heavily recruiting now-underemployed migrant workers to fill a new niche for cheap, and equally precarious, labor: COVID control. These migrant workers are now among the ranks of the dabai, or “big whites” as China calls them: the ubiquitous health monitors clothed in white protective gear — anonymous, yet essential to COVID policy….” (NPR, April 20)

Twitter thread comparing online protest related to the current situation in Shanghai with that related to the initial outbreak and state cover-up in Wuhan in 2020 (Guobin Yang, April 23):

WeChat wants people to use its video platform. So they did, for digital protests.

“A video protesting the Shanghai lockdown spread quickly on the app, as Chinese users raced to outwit censors and keep it alive.” (MIT Technology Review, April 24)

Has an NPC Spokesperson Declared Shanghai’s “Hard Isolation” Unlawful?

“After people discovered a set of 2020 Q&As by the NPC that appear to declare hard isolation unlawful, WeChat is censoring reposts of the Q&As & the NPC itself has also deleted them from its website, though they’re still widely avail online.” (NPC Observer, April 26)

Students protest harsh lockdown conditions and penalties

“Harsh lockdown conditions and draconian penalties for breaking them have led to a major student protest on the campus of Shanghai’s prestigious Fudan University and an angry petition to Duke Kunshan University (DKU) authorities, condemning the university’s harsh penalties for student non-compliance that include suspension from the Sino-American university.” (University World News, April 26)8

Shanghai Uses Crowdsourcing to Survive Covid-19 Lockdown as Social Support Breaks Down

“Now, ordinary citizens have stepped up to fill the breach. Volunteers, some of them engineers and programmers at China’s biggest technology firms, have built an array of databases and networks to help provide disaster relief and information on medical care, pet shelters, how to cook with limited ingredients and other essential information. That is helping keep the city of 25 million afloat as some hospitals and public transportation are inaccessible and people remain locked in their homes.” (WSJ, April 28)

Student poetry contest in China becomes unexpected outlet for dissent

“Even as the poems were censored, they still circulated through social media, with themes of lockdown alienation, poverty and even the war in Ukraine.” (Washington Post, April 24)

Translations of two of the censored poems (from the report):

Her Teeth9

by Huang Yanfang

Her teeth

The most fragile in the world

Cannot chew off the misery she did not deserve

It only takes one slap

For the gum to shoot them all out

And her teeth

Also the strongest

Even after the slap

Remain on the iron chain

Biting this nation’s heart

***

Kyiv

by Qiu Shuo

Chess pieces are placed, cold

Dusk light rises to the gate

And the square

In the distance, some people revel as if in an ancient ritual

In fits of laughter, a bomb explodes

Shrapnel shoots through my lover’s skull.

Previous Monthly News Highlights

Controlling the Soul’s Thirst for Freedom: News Highlights, March 2022

Chains of Patriarchy, Death from Overwork, Silenced Critics of War: News Highlights, February 2022

Drinking Algae, Folding Beijing, Fighting Lockdowns: News Highlights, January 2022

Fake Capital, Persecuted Speculators & Exploited Enterprises: News Highlights, December 2021

Notes

- After this month, we will slow down to one post every two months in order to set aside more time to work on the third issue of our journal and our next book, so the next post will be published around July 1 and deal with May-June.

- For an English report, see Shanghai Doctor Speaks Out Against China’s Covid Policy, Strikes a Nerve With Weary Public (WSJ, April 7, behind paywall).

- We also know from conversations with friends that there are other perspectives closer to our own that just aren’t being published there.

- 天理, a Neo-Confucian concept similar to “laws of nature.”

- The thread was taken down, so this is the backup on Internet Archive. If the page for any of these backups appears and then disappears after a few seconds of loading, try connecting from the hyperlink again and then click the “x” in your browser (or “stop loading”) before it disappears.

- There’s been some discussion about what “volunteer” means in the context of China’s pandemic control system. In this case and others it doesn’t usually mean “someone who decided they want to help” but instead means either party members ordered to help out in a specific place, or people who signed up as low-wage, flexible labor through a fund to encourage volunteering with other tasks, like promoting community garbage sorting, and were then pressured to continue to support pandemic prevention work.

- A number of trolls have claimed that the worker was drunk or “crazy” and that eggs could be obtained nearby, so this video is somehow fake or inconsequential. Other commenters have responded that even if the man was drunk, that wouldn’t have changed the underlying fact that Shanghai’s official policy has severely limited migrants’ access to food and other supplies, resulting in the sort of widespread hunger and desperation demonstrated by many other videos (including several samples in this blog post). Even if this particular worker managed to access alcohol or eggs, is he expected to live on that alone? His gratitude upon receiving the bananas and crackers, and his insistence that the people in the truck record and publicize his condition, should be enough to make clear that something is deeply wrong.

- Other sources have indicated that this report exaggerates what actually happened on Fudan campus: reportedly, there was no assembly of people of campus, and no one was arrested. Instead, campus CCP authorities or possibly internet police “invited to tea” students who had put up posters criticizing the policies.

- This poem refers to “the chained woman” of Feng County, Jiangsu — discussed in our February news highlights. Chinese original: 她的牙 / 是世界上最脆弱的牙 / 嚼也嚼不烂这无妄的苦难 / 所有牙齿飞离牙床 / 只消一记耳光 / 她的牙 / 是世界上最坚硬的牙 / 即使被打落 / 仍紧咬住锁链 / 紧咬住一个民族的良心。We have been unable to find the original Chinese version of the poem translated here as “Kyiv,” but some of the other poems and Chinese discussions of their reception and censorship may be found online by searching 2022全球华语大学生短诗大赛.