This post is the fourth in a series of monthly summaries of highlights from Chinese-language news and social media, offering some analysis of economic trends and the changing character of class struggle in China. Through these posts, we hope to give English readers a broader sample of the discussions taking place across the linguistic and digital divide. In addition, we recommend a few recent English-language publications at the end. (If you notice mistakes or any important story that we missed, please contact as chuangcn@riseup.net and we can add it to next month’s post.)

Highlights from Chinese News and Social Media, March 2022

Lowering Taxes for the Rich in Response to Economic Downturn

This year’s “Two Sessions” (两会), one of the regular political rituals in China, took place in early March. Premier Li Keqiang admitted that China’s economy has been facing more complex and uncertain external and domestic conditions, including three facets of pressure on the economy: shrinking demand, problems with supply, and “weakened expectations.”

While “problems with supply” consists mainly of the rising prices for commodities (petroleum, metals and agricultural products) in international markets (worsened by the conflict between Ukraine and Russia), the other two facets are more about domestic conditions. “Demand” in economics usually refers to consumer demand, but in China the emphasis is often more on commercial demand from firms. In fact, one official argued that the prime solution to reviving consumption demands was to help enterprises.

What about “weakened expectations?” Premier Li gave us an answer (providing a rare glimpse into the central state’s policy-making): he gave entrepreneurs three options to support them: more investment, vouchers for consumers, and less taxes and fees. “They were silent for a while, then almost unanimously they chose the third,” since that was the most “direct, fair and efficient” one. Of course, no workers were invited to participate in these discussions.

Tough Pandemic Restrictions Continue, alongside Protests & Costs

Beijing seems to be pulling its hair out over the COVID situation in March, with particularly intense lockdown measures throughout the country over the past few months, continued problems and protests in response, and a special meeting of the Politburo’s Standing Committee (China’s most powerful state organ) that finally acknowledged the economic and social costs of the nation’s stringent control measures.

Despite the official continuation of China’s zero-COVID policy, the state has begun to make minor adjustments of its guidelines for treatment—considering that over half of new cases have been asymptomatic, and that NAAT testing for every minor outbreak has become a drain on resources. Previously, anyone who tested positive was forced go to the hospital for treatment and then (after recovering and testing negative) quarantine at home for another 14 days. Now, in mild and asymptomatic cases, patients only have to quarantine at home (requiring hospitalization only in more severe cases), and in all cases, after recovering and testing negative, patients only have to quarantine at home for another 7 days. However, it remains to be seen how these new guidelines will be implemented at the local level, where stringent lockdowns and their attendant problems and protests continue.

Shenzhen

Before this meeting there was a small outbreak in Shenzhen, and the local government addressed this with harsh restrictions:

Delivery workers are one of the groups most impacted by such sudden restrictions. After one day’s work they were about to go back home and rest, only to find their complexes were on lockdown, and they had only two options: either enter, be subject to restriction and not making money, or stay outside overnight. Some of them joked that it would be better to get infected and receive the subsidy of 500 yuan (79 USD) per day.

If you are interested in the way local networks of “healthcare volunteers” and government policy works, here’s a lively record of daily lives under quarantine in Shenzhen (video in Chinese only). In it our hosts were faced with different interpretations for the same policy (“how many tests should we take per week”), a feeling of isolation and indolence for not doing anything, and an attempt to make things better by dyeing hair and preparing groceries. (That video has been taken down now but also check out this video interview with workers in Shenzhen during the lockdown.)

Shanghai

For a long time Shanghai stood out as an exception from the indiscriminately strict pandemic measures that predominated elsewhere in China. But this came to an end after the central government allegedly criticized the municipality for “arrogantly creating its own policies” (自以为是自作主张) on March 15th, even while new cases during the “lax” period in question fell from a peak of 42 to only 15. On March 27th Shanghai decided to have a mass testing and lockdown for 4 districts and numerous smaller areas, effectively covering the whole city only in a consecutive way: first east to Huangpu River, then the west.

A local official announced on TV that people should “control their souls’ thirst for freedom” (控制灵魂对自由的渴望)—which went viral and became a meme—and later he suggested that people shouldn’t feel guilty about wasting their own lives during a long-lasting lockdown. Note that this speech was from March 1st, so this couldn’t be more ironic after Shanghai increased restrictions.

Interestingly, Shanghai did not implement such policies with wholesale agreement. Since 2020 Shanghai has been burdened with almost 40% of international flights lines, partly because Beijing diverted some of its international ones to it. Thus Shanghai has a higher possibility of outbreak from immigration in the first place. Besides, Shanghai is one of the engines for Chinese economy: in 2021 Shanghai had a GDP of more than 4 trillion yuan (628 million USD), the highest among Chinese cities. A full lockdown could lead to serious economic repercussions, as explained by this official from local medical school:

I saw some suggestions online that “let’s get determined and have a lockdown for 3-5 days, maybe a week, no?” No. Why? Because Shanghai, our city Shanghai, carries more than a city of our Shanghai people; it carries an important role in the national economic and social development… if our city stopped functioning, the East China Sea should be filled with floating international cargo ships, and the whole national and global economy could be impacted.

In these waves of quarantine and testing we could feel the desparation of Shanghai to balance between less economic downtrend and quicker pandemic controlling.

Meanwhile, nurses at Shanghai’s Zhoupu hospital went on strike on or about the 21nd of March following a decision to have positive Covid cases gathered at their hospital, according to a story from Hong Kong’s Ming Pao newspaper. The nurses, nearly all women according to videos, said there were plans to convert the hospital into a “fangcang hospital” (方舱医院) or makeshift field hospital to deal with large numbers of Covid patients, without any form of compensation for the nurses. One video showed a tearful nurse negotiating with higherups, who said hospital workers worked night and day performing Covid tests, going 36 hours without sleep. The hospital had suddenly sealed all the windows without warning, stifling any air flow through their workplace. Other grievances include the lack of security guards on night shifts to help deal with disgruntled patients.

Another example of rigid quarantine happened in a local retail market. Two weeks ago over one hundred shop owners from the market were confirmed positive, and thousands of people were quarantined. They had to sleep on the concrete ground at night. According to those present, no one came to the market to treat them or give instructions, and their calls for help went unanswered.

Changchun

A relatively large Omicron outbreak in the Jilin province last week has resulted in over 4 million people being placed under various levels of lockdown. The province, following the nationwide standard, commissioned the construction of over a dozen makeshift hospitals to aid the response and to quarantine the infected. This rapid deployment of resources was lauded in state media as an example of China’s growing state capacity.

From afar, it’s not hard to envy such a response while other states continue to flounder with even the most basic responses to the virus. But a closer look shows that building these hospitals is more complicated than the state simply issuing a decree. These hospitals were built by workers and financed by capital, and not even a national disaster can interrupt the capital-labor relation.

Not long after the hospitals’ construction, migrant workers on the project took to social media to voice their concerns. Traveling to Changchun, Jilin from Harbin, the workers were told that they would have to cover their own room and board for self-isolation, with the construction company only subsidizing 60% of the cost. Upon arriving, they found that no quarantine quarters had actually been put aside for them, with the company forcing them into a dingy, frozen dormitory with no power or heat.

To add insult to injury, the workers were informed upon the project’s completion that they wouldn’t be paid their wages, wouldn’t be paid their quarantine subsidy, and wouldn’t be able to return home, as several of them had by then contracted the virus while living in such dilapidated conditions. The absurd situation led to a number of small protests before being resolved by higher authorities from the city government.

While this may have been the most egregious example, it’s not hard to imagine similar scenarios happening at the other makeshift hospitals across the country.

Hangzhou

Hangzhou’s Sijiqing (四季青) Apparel Market is the biggest source of garments retailed domestically throughout China. In 2011 it came to be a congregation of more than 8,000 garment wholesalers supplying retailers throughout the country. In 2016 the sales in this market consisted of more than 50% of Hangzhou’s GDP. Some even claimed that if suppply from this market stopped, the whole apparel section of Taobao (China’s rough equivalent to Amazon) would be finished.

In early March, a confirmed case of COVID emerged in the market. Although this lone case was quickly locked in and contained, this came at the expense of a tough lockdown. Shops were told they could only sell existing stock and could not make any new purchases (只出不进) even after two weeks’ quarantine. Theoretically these owners could sell their inventories, but most had run out in the beginning of quarantine when all shop had to close and the clients still asked for supplies. “What’s the point of [this policy] if we had no inventory at all?”

4 days later a protest broke out. Shop owners demanded less rent and an explanation for tough restrictions. Some were arrested. An executive of Sijiqing was present and admitted it was a difficult situation, but their damand for less rent should be considered along with the whole city’s market from other industries. “This is a calibrated process, not a policy of rush-and-go.” So far there was no further news about those arrested or how Hangzhou should address to this.

Disappearance of Wuyi, Supporter of “the Chained Woman of Feng County”

Last month we mentioned that Wuyi went to Feng County trying to visit the chained woman. A few weeks later she lost all connection to the world, presumably arrested by the local police, before going to leave for where the chained woman was born. It was highly likely that she was under residential surveillance. (Now her lawyer has confirmed that she is in police custody, but the police have still not issued any official documents to the family indicating why she has been detained, as required by law.)

On March 14th another supporter with ID “Drinkerliveslonger” visited Feng County, but had to turn around after stopped by a check station about 2 kilometers from the village. She recorded the journey and posted her photos on Weibo with ironic captions. “You can arrest a Wuyi as you want, but we would never give up. Act in secret, if not in public. Sneak in night, if not in daytime.” The post was quickly censored. 2 days later she posted that “I’m basically fine, but not without danger.” (基本平安,但不是没有危险)

The silent protest went on. An anonymous artist painted a mural for the chained woman. Some children of abducted mothers took an interview about their thoughts: one did not think his mother was poorly treated because he was the more miserable one; one felt sorry for his mother and sympathetic about her leaving home, not seeing each other again; one prefer herself not born to this world in the first pace, because she was wary of thinking of her mother at all.

What are Construction Workers to Do upon Retirement?

The Worker’s Daily published a report about elderly migrant workers in the construction industry. In the last few years, local governments have been prohibiting companies from employing “elderly” construction workers (usually over the age of 60 but differing by city) in the name of protecting their security and health (but likely also out of concern for unrest when injured elderly workers seek compensation, as often happens). If they are still willing to take jobs, the company is encouraged to provide more relaxing jobs like security and cleaning.

But such policies seem to ignore a simple fact: what if these elderly migrant workers cannot find a job? Relaxing jobs like security are so much less. If there were demands that company should improve worker’s conditions, companies would offset this cost by reducing workers’ salary, and workers would prefer less favourable conditions for more earnings, as analyzed here. All these competing situations should squeeze workers’ power to negotiate in the labour market. Even if they went back to their rural home, they would earn so much less than what they could in cities, and the pension could barely cover the living cost.

According to official data, in 2019 24.6% of migrant workers were 50 years old or older, and about 54 million were construction workers consisting of 18.88% in the whole. Before the report from Worker’s Daily, a video of a 52-year-old worker went viral online: he left his hometown for Zhengzhou, capital city of Henan province, had a lunch of 5 yuan (0.78 USD) per day, and did the hard work of carrying things at construction sites. In order to save more money he slept under the highway bridge without a sheet, so that he could buy more tools for more work. “I think I can pull through in three days with some five dozen yuan.”

Subsidy for Peasants Not Really as Imagined

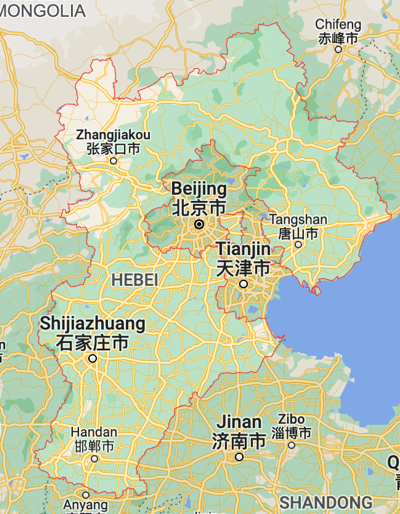

In late March, Hebei province decided to give out a subsidy of more than 1.1 billion yuan (0.17 billion USD) to local peasants, who were burdened with higher costs of agricultural inputs along with a rise of commodity prices. But there are things hidden behind this benevolent policy.

Geographically Hebei is a province surrounding the whole city of Beijing like a donut, and economically Hebei has been squeezed by the capital for a long time. After the mid-1990s Hebei’s economy began to fall behind, from being the 5th wealthiest province in the nation back then to becoming the 12th in 2020. One of the reasons, or perhaps the major one, is that Hebei has to support Beijing at nearly all cost, especially after Beijing vowed to become an environmentally friendly city. One example is the campaign of “coal to liquefied natural gas” (煤改气), when Hebei had to follow stringent orders to reduce coal’s usage for better air quality.

Specifically, Hebei’s agriculture is subject to the greater projects of the capital city as well. Take underground water as an example. For a long time Hebei has over-drained underground water to an astonishing extent, because many local reservoirs are exclusively channelled to Beijing . In 2019 the over-drained volume of water has consisted of a whole third of the national total. Local governments tried to revert it by giving out subsidy and encouraging diversified crops. In spite of it, subsidy was again and again embezzled by bureaucrats, and local peasants had to deal with a myriad of forces majeures, like the tricky company giving them bad seeds, better income in cities, and specific requirements for some crops.

More lively comments can be seen on Zhihu (Chinese version of Quora). To quote some of the most liked comments:

“A grand narrative like this is the most susceptible to corruption. Outsiders would only know a subsidy of 1.1 billion yuan, but no one could tell the difference if only 0.5 or 0.1 billion were dispersed. People would think it must be too many qualifiers.”

“Interest involved: 3 acres of land from my family…. I remember back in the 1990s when we had to pay some 300 yuan per year to feed those huge packs of civil servants…. That’s why our brothers in Jiangxi should be remembered forever in history.”[1]

“According to past experience, 11 billion should be a huge sum, but… dispensed in average, you’d get only 11 yuan per acre…. The price of chemical fertilizer has risen from 110 yuan [per half kilo?] to 145; pesticide from 7 to 12…. Peasants’ willingness to farm keeps fading away…. While the price of wheat is rising, the price of fruit and vegetables is skyrocketing, so now peasants understand that all the money they earned has to be taken away from all sides.”

Hong Kong Might Remain Autonomous after 2047?

After treating Cantonese with less satire in a official gala (see our last highlight), the Chinese state tried to console Hongkongers again by reaffirming that “the CCP won’t substitute Hong Kong for its own governance.” The head of Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office (HKMAO) promised that the policy of “One Country, Two Systems” (semi-autonomy) could remain after 2047 if it goes in the right course. Take the pandemic as example, he said, when the central could give out directions to the Chief Executive but at the same time respect Hong Kong’s different system.

In spite of this, Hong Kong’s pandemic policy has been criticized as slow and ineffective since February, and the mainland saw a huge increase in immigration from Hong Kong hoping to leave as soon as possible. Some tended to illegal means to return to mainland and became local confirmed COVID cases.

“Fucking Capitalist” Tells the Poor to Rent out Their Surplus Homes

Elitist comments on China’s poor from Xu Xianchun, former deputy director of the National Bureau of Statistics, led to laughs and scorn on social media. The comment arose in a discussion of unemployment among China’s ballooning college graduate population, and the problems of “flexible employment” (灵活就业), roughly equivalent to what most call “precarious work,” or “informal employment” in English-language discourse.

Xu lauded the benefits of the informal economy and gig work as a benefit to the poor. “As for flexible employment, let’s say you own a vehicle, then you can haul goods for a living. As for the employment problem, and solving the problems of low-income people, I feel that this is an effective method. Or, for example, if you rent out a vacant house that you own, that’s also a way to make extra income.”

The interview was replete with out-of-touch and dismissive comments by two bourgeois parasites. In a clip of the interview available on Youtube, interviewer Su Qi of Caijing said “Young people these days don’t like 996, and don’t like involution (neijuan 内卷),” referring to the culture of working 9am to 9pm, six days a week, and involution, or “turning inward,” describing a sense of frustration that the present system is stagnating, with no hope of change for the better.

“This year they’ve started to change their tone,” Su continued, as both of them started to laugh. “They feel that they’re really lucky to have 996,” to which Xu responded “Yes!” with a smile. “First (they want to) hold on to their livelihood,” Su said.

Su and Xu also discuss the high unemployment rate for China’s college graduates, and the alarming rate of growth in the number of grads. The two note that the number of new college grads each year has quickly climbed from 8 million to 10 million. This year, 11 million grads will move onto the job market, and unemployment for young people between 16 and 24 years old sits at 15 percent according to official statistics. Xu said some of the unemployment pressure was due to COVID, and lower demand from firms. But Xu added that the generally high unemployment rate in new grads in summer months distorts the overall unemployment figure.

Netizens scoffed at Xu, who now works as a professor at the Tsinghua University School of Economics and Management. “Our party members now have no idea about the living conditions of the people,” read one popular post with a screen capture of Xu’s comments on hauling freight to get by and renting out one’s spare homes. Another popular post cursed Xu as a “fucking capitalist” (狗日的资本家) and traitor against the working class and socialism:

“I’m laughing my ass off, Xu Xianchun, you old dog cunt! Fucking capitalist and traitor against the working class and socialism! Renting out vacant homes? Could people with extra homes to spare belong to those with low income? Are you talking about your mom? Why won’t you die already? … And you, Caijing Magazine, you’re all full of shit, you should be hanged on a lamppost!”

笑你妈呢许宪春!老狗逼!狗日的资本家,工人阶级、社会主义的叛徒!闲置房租出去,能有闲置房的是低收入群体?你说你妈呢?你咋不去死呢?#经济# #资本家可真有你的# #灵活就业# #工人阶级# 还有你们财经杂志,没一个好东西,都该挂在路灯上!

New English Publications

The Concrete Plateau: Urban Tibetans and the Chinese Civilizing Machine

New book by Andrew Grant

“In The Concrete Plateau, Andrew Grant examines the ways that urbanization has extended into the Tibetan Plateau. Many people still think of Tibetans as not being urban, or that if they do live in cities, this means that they have lost something. Much of this is relates to the expectation that urbanization can only erode essential aspects of Tibetan culture. Grant pushes back against this notion through his in-depth exploration of Tibetans’ experiences with urban life in the growing city of Xining, the largest city on the Tibetan Plateau.”

China’s Gig Workers Are Challenging Their Algorithmic Bosses

“Food delivery drivers are using platforms’ data-powered systems, mass WeChat groups, and unofficial unions to fight unfair conditions.” (Wired, March 14)

Being Water: Streams of Hong Kong Futures

“this issue of the Made in China Journal takes stock of the aftermath of the protest movement and reflects on the changes that are taking place in Hong Kong’s political and civil society in the post-NSL era.”

Internationalism amidst repression: Hong Kong students against the war in Ukraine

“A response to the state’s reactionary attack against Hong Kong students’ solidarity with Ukraine” by a group of Hong Kong University Students and Socialism Defenders (Lausan, March 28)

New Directions of Leftist Organizing in Post-Socialist China

“Groups like Queer Workers and incidents like that at Guangdong University of Technology suggest that the global Left has to build politics not exclusively on the grounds of anti-authoritarianism but on critical and community-based organizing across the landscape of “villages within cities (城中村)” in post-socialist China.” (Upping the Anti, January 30)

Previous Monthly News Highlights

Notes

[1] This is a reference of Fengcheng Incident (丰城事件) in Jiangxi province. In August 2000, a peasant spreaded some open official documents of lessening rural burdens and excited a riot against high fees. There are lots of uncertained details here, like the peasant spreading documents got arrested and died suspiciously, and some cadres got caught and buried alive by furious villagers. But official data shows that “event of masses” (群体性事件), an euphemesim for massive protest or riot, reached more than 30,000 in first nine months of 2000. For an overview and analysis of such rural struggles during that era, see “Gleaning the Welfare Fields” in the first issue of our journal. (The link for a source on the Fengcheng Incident has been creating a technical error for our website, but may be found by searching the title: 二十余来大陆农村的政治稳定状况 ——以农民行动的变化为视角 by 肖唐镖.)