This post is the second in a series of monthly summaries of highlights from Chinese-language news and social media, offering some analysis of economic trends and the changing character of class struggle in China. Through these posts, we hope to give English readers a broader sample of the discussions taking place across the linguistic and digital divide. In addition, we recommend a few recent English-language publications at the end. (If you notice anything major that we missed, please contact as chuangcn@riseup.net and we can add it to next month’s post.)

Highlights from Chinese News and Social Media, January 2022

Lockdowns throughout China Spark Protests

On the eve of the Winter Olympics, China was still addressing COVID-19 with tough restrictions. Although the National Health Commission stated that this pandemic should not be dealt with in a simplified and “clean-cut” way, local governments had and still were pushing forward coercive policies like a rushing bull. Residents and especially migrants in several cities impacted by such policies reacted in similar ways: protests and even violent clashes.

Xi’an

A residential complex “Huacheng International” (华城国际) in Xi’an was locked down from December 17 to January 19. That night homeowners got a notice from the property management (物业) that the lockdown would end the next day, but on January 20 they got another notice that the lockdown would continue for two more days. A furious crowd rushed to the property management for further answers. Police got there and made arrests of unknown numbers. People shouted “Release the people! (放人)” The same night officials declared that the district where this complex located should downgrade its restriction.

Tianjin

A crowd of migrant workers in Dasi township, Xiqing district of Tianjin, which is under strict covid lockdown, rose up in protest after the local government allegedly gave food to residents, but not non-residents who make the city run. They shouted “What will we outsiders eat?!” “We want to eat our fill. Does the Chinese Communist Party support us?” When asked by the police to select a representative for negotiation, they answered “we don’t have a representative” and “we each represent our own”.

Shenzhen

Shenzhen has stepped up virus control measures after more cases were reported over mid-January. Protesters in Tianxin village, part of Luohuo district, saw lockdown measures after a confirmed Covid case visited there a few days ago. They shouted “open up!” or “end the lockdown”. Video shows clashes with police, at least one man hauled off by cops.

Local Officials Threaten Detention for New Year Returnees

Returning to one’s hometown for the Spring Festival, centered around the lunisolar New Year, is a Chinese tradition that long predates the Chinese Communist Party. The holiday is especially important for China’s migrant workers, among the millions of people who work far from where they were born. China’s Spring Migration (春运) has been called the largest movement of humans on the planet, as workers attempt to return home before the lunisolar New Year’s Eve (除夕)—this year falling on January 31st—to be with their families.

This is China’s third Spring Festival under the pandemic. With restrictions on movement and quarantine measures tightened in virulent winter months, many have not returned home at all, on local government instructions. For example, after the Xi’an outbreak, the Shaanxi government told migrant workers to prepare to stay in place for the holiday. Reports poured in from across China about local officials throwing returnees into quarantine, or even detention, regardless of where they came from.

One county head in Dancheng, Henan said in a video conference on January 20: “For anyone who returns home, first you’ll be quarantined, then detained,” in a threat to migrant workers. The threat, and others like it, received nation-wide ridicule, and even some push-back from Beijing. The Dancheng case was chided by China’s Central Television as arbitrary and excessive. Even after this head clarified that his original words had been taken out of the context (only those “maliciously returning” (恶意返乡) would be dealt with), the words came too late for most of those who would had already returned home, if threats had not come first. The city of Beijing, for example, has still insisted that those who don’t need to leave should not.

This year, preliminary figures from China’s Ministry of Transportation show that the number of travelers during the Spring Migration is higher than last year, but still far below the numbers from before the pandemic. This year, as of January 29th, there were 351 million journeys logged as Spring Festival return journeys. The figure is just two-thirds the number from the last Spring Festival before the pandemic, but still almost 50 percent more than those who returned home last year in early 2021. As people tired of strict pandemic controls, the desire to return home is strong, despite warnings from the state. Even prominent Chinese legal experts are beginning to openly critique excessive “campaign style” virus control measures, after recent disasters in Xi’an and elsewhere.

Delivery Workers Mired in an Ever-Expanding Legal Labyrinth

A legal advocacy group focused on migrant workers gave a talk on the evolution of the “dark web of legal relations” delivery workers1 find themselves in, which increasingly obfuscates the employment relationship between the worker and the delivery platform, so as to evade certain legal responsibilities such as insurance, benefits and reparations for work-incurred injuries. You can find the transcript here, and a more detailed report on delivery workers’ working conditions here.

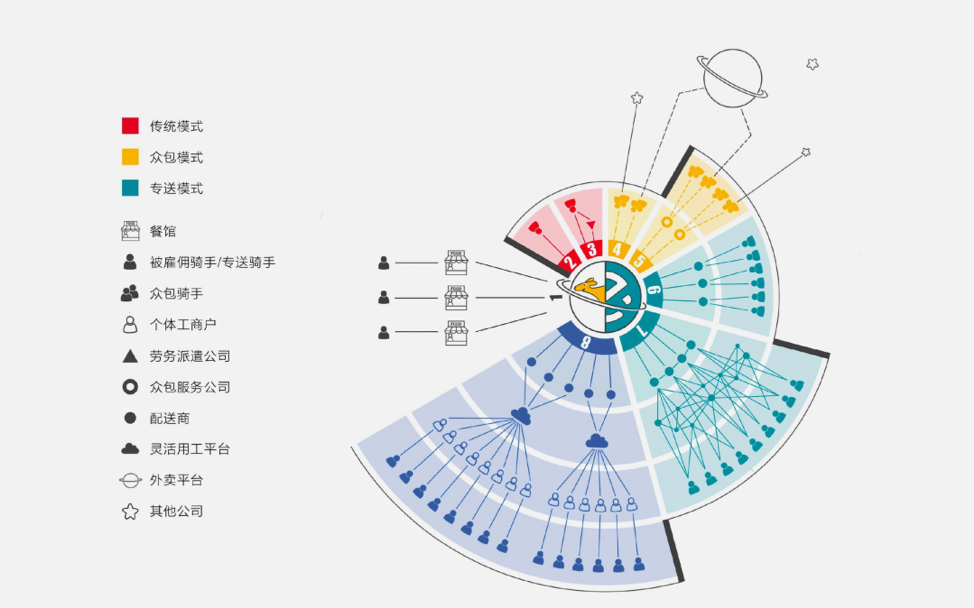

According to their analysis, over the last decade or so, the model of labor deployment evolved through a series of eight stages of increasing convolution.

Today, it’s typical for a delivery worker to be four degrees removed from the food delivery platform:

delivery worker — individual industrial and commercial household — flexible work platform — distributor — food delivery platform

Notably, in a recent innovation, delivery platforms have started to have delivery workers registered as “individual industrial and commercial households” (个体户), a move that turns the legal status of the delivery worker into that of an enterprise, with which the platform maintains a commercial “partnership” rather than a relation of employment. Suffice it to say, this innovation has been successful. In the last three evolutionary stages, according to their analysis of 1,907 court documents, the delivery platform has less than a one percent chance of being recognized by the judicial system as an employer. Instead, this status is often offloaded onto distributors. However, the distributors usually have a low operating budget (if they have one at all), and so they are often unable to fulfill their legal obligations. 14.1% of them are even unregistered. What’s more, there are usually multiple distributors making use of the same worker simultaneously. Altogether, these developments only darken the already grim prospects for workers seeking compensation through legal channels. (This parallels similar developments in Europe.)2

An Eventful Month for Real Estate and the Intermediate Strata

On January 17th China released a package of economic data about the fourth quarter of 2021, and the year as a whole. While the National Bureau of Statistics celebrated the outcomes, a closer look at the actual data revealed clear negative trends: quarterly GDP growth and added value in industrial enterprises remained stagnant; December 2021 retail sales of social consumer goods grew 1.7% compared with last December, the lowest among other months this year, and fell to -0.18% compared to November; not to mention that the growth of real estate development investment reached the lowest in 17 months.

But as economic fundamentals show worrying signs, policy makers appear to have doubled down on the property market, which has grown to play a central, yet increasingly precarious, role in China’s growth. After China’s central bank lowered the Reserve Requirement Ratio and Loan Prime Rate (LPR) last December, interest rates were cut again in January, specifically LPR, a benchmark for loans from banks to enterprises, though it is also linked to mortgage rates. Some have speculated the rate cut would make it easier for property developers to access funds from sales still held in escrow accounts.

Economic conditions are gloomy for the population as a whole, but of course they affect different strata of China’s class structure in different ways. As we noted in our analysis of the changing cadence of class struggle in China, it’s worth watching closely what may happen with China’s well-to-do or “intermediate strata,” as social struggles related to disgruntled homeowners has grown year over year, while events like strikes and protests among manufacturing workers, for example, have become less prominent than they were a decade ago.

Official rhetoric was tinged with unease over the fate of the property market. A deputy governor from the central bank warned that “collapse in credit growth” (信贷塌方) must be avoided. The National Development and Reform Commission published a notice in order to “support the commercial housing market” to better meet “reasonable housing demand.” A professor in finance revealed that four greatest state-owned commercial banks charged 200,000 property owners for foreclosure this month.

In fact a poll suggested that 60% of homeowners would choose foreclosure should be housing price plummet. From some comments below, we can take the pulse of the intermediate strata as they panic about threats to the value of their homes:

I’m in foreclosure already. Bought a house at a Beijing suburb worth 2.3 million yuan (0.36 million USD), mortgage 1.3 million yuan (0.21 m USD), paid for a year. After foreclosure, my house was auctioned for 1.1 million yuan (0.17 m USD), and I lost a total of 1.5 million (0.24 m USD) including down payment, taxes, broker services, and what I paid for the first year of loan. Now I lost my house, and still in debt of the bank for 0.26 million yuan (41,017 USD), not to mention the court fee. Alas, my consumption was limited too (for a low social credit score).

I’m 32, have a loan of 3 million yuan (470,000 USD), monthly payment 18,000 yuan (2,839 USD), down payment 50% of total. It seems normal to have monthly payment this high in first-tier cities, but I’m scared that an accident could cause me to lose income. And I gotta support my child and that means lots of expenses. Lucky that I got another house free and clear, and I can sell it if anything happens. My husband was thinking of selling it in order to buy a third one with higher leverage, but I strongly refused. You feel everything’s easy when you have a nice income, but everything goes south once there’s an accident.

I bought a car in Shanghai last year. Mortgage monthly payment 25000 yuan (3943 USD). I survived 2020 thanks to Housing Provident Fund, but I don’t know what should happen in 2021. My industry didn’t perform well. I can cover the mortgage if my salary got leveled up as normal, but this pandemic has affected my whole income per month, so the mortgage is barely covered if HPF included. I’m so upset.

Prole Virus, Bougie Virus

The story behind one positive Covid case in Beijing led to a widespread public discussion, and its subsequent censorship, after it uncovered a tragic tale of a poor man from Shandong and his search for his lost son.

On January 19th, the travel records of the man, surnamed Qiu, went viral online. Officials revealed that his primary job was carrying construction materials, though from the list below, you’ll find his life was more complex:

Jan 1 23:30 – Jan 2 4:43, worked in a hotel.

Jan 2 23:00 – Jan 3 3:00, worked in a construction site near a theatre.

Jan 3 21:00 – Jan 4 1:37, worked in a residential complex (小区) and a rubbish collection station.

Jan 4 14:00 – 14:30, worked in a villa.

Jan 5 12:00, worked in a house unit. 16:00 and 17:00, worked at two construction sites.

Jan 6 11:00 – 12:08, worked in a residential complex. 14:21 and 21:06, worked in two factories. 21:30 — 23:04, worked in a building.

Jan 7 14:30, worked in a residential complex.

Jan 8 12:36, ate alone in a restaurant. 14:00 and 15:14, worked in two residential complexes. 17:00 – 21:30, worked in a house unit.

Jan 9 7:30 – 10:10, worked in a residential complex.

Jan 10 0:00 – 1:45, worked in a restaurant. 2:00, worked in another restaurant. 3:00, worked in an office building. 4:00, worked in an industry park. 9:00, worked in a villa.

Jan 11 2:58, worked in a construction site near a theatre. 23:00 – Jan 12 3:00, worked in an office building.

Jan 12 0:00 – 4:00 and 11:14, worked in the same house unit. 23:18 – Jan 13 3:43, worked in a construction site near a theatre.

Jan 13 19:00 – 20:00, worked in house units. 23:58 – Jan 14 5:05, worked in a shopping mall.

Jan 14 11:05 – 17:40, worked in a residential complex. 22:18 – Jan 15 3:51, worked in a construction site near a theatre.

The next day, on January 20th, China News Weekly interviewed Qiu, and revealed that he had come to Beijing to search for his missing son, while his wife stayed home in Shandong to take care of the younger son. During his days in Beijing, Qiu got a few odd jobs through Wechat day-labor groups to earn a living, though his main job was to transport construction materials or waste. He got paid 200-300 yuan (32-47 USD) for each job, and worked through the night because Beijing’s downtown bans construction truck travel during the day. Qiu lived in a room of 10 sqm with a monthly rent of 700 yuan (110 USD). However, the interview was banned from sharing on Wechat the same day it was published.

On January 21st, police in Qiu’s hometown in Shandong published an announcement that they had identified a corpse as Qiu’s son back in August 2020, but Mr. Qiu and the young man’s mother rejected the police findings. “The police explained, consoled and communicated patiently with the couple several times, but they still did not accept the results,” the police announcement read. Qiu later explained that corpse was not the same build as his son.

Though he came into the spotlight quite suddenly, Qiu insisted that he didn’t feel sorry for himself or intend to challenge the authorities. “I didn’t petition to report anyone. I just hoped that I could get more information and find my son as soon as possible.”

Compare the case of Qiu to another positive Covid case from Beijing, the first omicron case identified in the capital. Here is an abbreviated version of her 14 day travel record, published after she tested positive:

Jan 1 12:00 drove to Quanqude restaurant in the Tsinghua Science and Technology Park [Quanjude is perhaps China’s most famous Peking duck restaurant], 15:00 Take the subway with friends to Baita Temple, departed at 15:50, went to Lane Crawford store on the first floor of Financial Street Mall, drank coffee at the GREY BOX cafe on the basement floor, and shop at Ole’ supermarket on the basement floor.

Jan 2 Drove to SKP shopping mall with friends at 11:00 [Beijing’s most elite shopping mall]. Went shopping at Dior, financial street shopping center at 12:00. Dined at South Restaurant on the second floor of financial street shopping center at 14:10, and left at 15:02. From 17:00 to 18:30, watched a talk show in a theater on the B1 floor of Yongli International (No. 21, Chaoyang Gongti North Road), and drove home after the performance.

Jan 3 In the afternoon, drove with friends to the Walmart supermarket and left the 15:37. After that, went to Chow Tai Fook, Chow Sang Sang [two high end jewelry stores] and other stores in the mall, and then drove home.

From January 4th to 7th, took a private car to go to work at 6:30 every morning, and took bus No. 688 from Haidianqiao North to Xianghuangqi Station to go home at around 18:00. After getting home, went to McDonald’s on Nongda South Road to pick up a meal.

Jan 8 At 10:00, drove to Changping Reignwood Ecological Park Ski Resort by car, left around 13:00. Went to Western Mahua Beef Noodles for dinner, left at 13:22. Around 14:00 went to Aeon International Shopping Center for shopping, left at about 15:00.

Jan 9 At 11:18 took bus No. 688 from Shucun Station to Qinghe Xiaoying West Station. Went to a friend’s house, and walked to Qinghe Wanxianghui store with a friend at 15:00. Went shopping drove home.

Jan 10 to 13 Took a private car to work every morning at 6:30, and got off work at around 18:00 by bus No. 688 from Haidianqiao North to Xianghuangqi Station to get off and go home.

Jan 14 Took a private car to work at 6:30. Took a private car to the nucleic acid testing point (address is the southeast corner of the intersection of Danling Street and Haidian West Street, Haidian District) at 17:45 for nucleic acid testing, and then went home without going out.

Also see English reports on Sixth Tone, Quartz, and China Digital Times, where this juxtaposition is compared to Hao Jingfang’s 2012 sci-fi novella Folding Beijing, where the city’s social classes are physically segregated through dystopian means.

“Lying Flat” Forum Seeks Forgiveness from Cyber Police

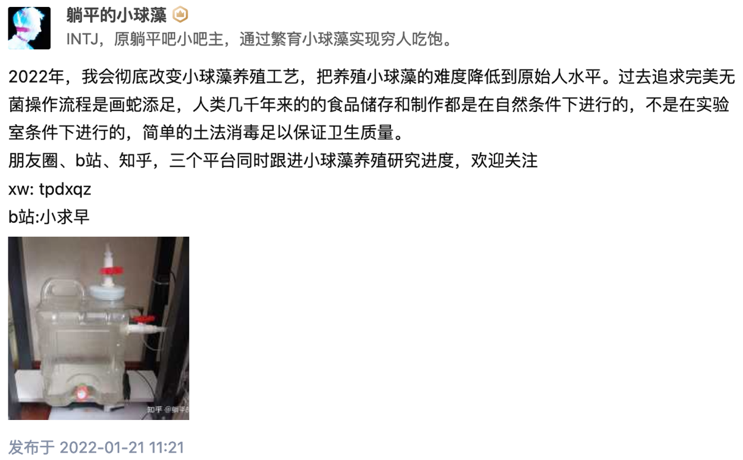

Last year someone later known as “Flat-Lying Little Algae (躺平的小球藻)” went viral after they posted how they were trying to survive by drinking algae, titled “as long as there’s light, I won’t starve to death.” Posted in the “Lie-Flat Forum” (躺平吧)—a Chinese equivalent to a subreddit—this quickly attracted attention since the author did thorough research on the nutrition and growth of algae. Although this post was deleted for unknown reasons (possibly because this was against the state’s admonition “do not lie flat”), the author was still active on Zhihu (知乎), a Chinese equivalent to Quora. But even then the state seemed to insist on their mandate, and there should be no exception of censorship.

On January 21st everything seemed undisturbed: they had set a goal for 2022 to “completely change the art” of growing algae so that it should be easier.

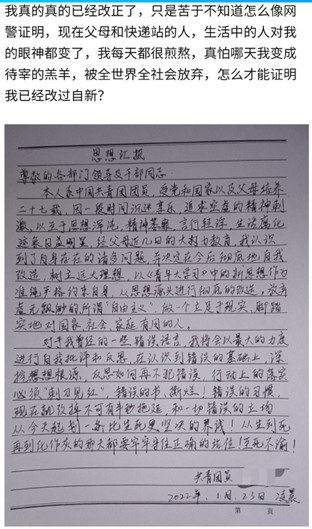

But three days later, on January 24th, Flat-Lying Little Algae posted a question: “How can I prove to the cyber police that I’m completely rehabilitated?” followed by their letter of self-criticism:

Question: “I was naïve back when I was young, and I was experiencing mental disturbances for a while, which made me say something inappropriate. Later it became apparent that some cadres and staff contacted my parents and someone in my residential community (shequ) asking them to watch over me…. My recent life has been like The Truman Show: not only my parents but staff in the delivery station have all been looking at me at oddly. And because I’ve been unemployed for a long time, right now I’ve become a target of discrimination and surveillance. I was diagnosed with depression but I treated everyone politely…. I have truly been rehabilitated, the only problem is that I don’t know how to prove this to the cyber police….”

Letter: “I am a member of Chinese Youth League, and have been cultivated by the party, the country and my parents for whole 27 years. For an addiction of hedonism and a pursuit of empty stimulant in spirit, my mind turned chaotic, my soul inanimate, my behavior frivolous, my life increasingly decadent. After a few days’ pedagogy from my parents, I acknowledged all these issues from myself and was determined to undergo a complete self-transformation….”

Then they posted that they felt regretful for making “decadent” statements in the past and asked to be watched over, and that they were determined to become a “useful” person.

This all too abrupt turn feels so ridiculous that we cannot help wondering what kind of coercion they had to be facing. It must be noted that we cannot prove whether cyber police or “cadres” did contact their parents, and we cannot rule out that paranoia might have played a role. But the stress just brought by posting how to survive with the lowest possible cost should be alarming and tragic enough.

A Tencent Employee’s Resignation Sparks Debate about Unpaid Overtime

On January 25th a work team at Tencent received a reward from their supervisors: This team worked endlessly for more than 20 hours to make sure an advertisement went online on time, finishing more than 200 code checks and corrections in a week with high intensity. The only problem was that one member didn’t feel encouraged by this, and instead questioned his supervisors: “Have you ever thought about your subordinates’ life and death?”

“I’ll always keep this screenshot of encouragement. Let’s enjoy this dark humor that slow murder should be deemed as an honor…. Someday I’ll paste this on Tencent’s tombstone.” “I’ll hand in my resignation tomorrow. Hope you guys accept it so that I can enjoy the next year in peace.”

In this long message, Zhang Yifei (张义飞) recalled how one of his high-school classmates, employed as developer like him, died of a stroke, presumably because of working too many hours. He hoped everyone could take a minute to think about this: Is it really worth sacrificing your young, healthy body for a so-called reward and a few thousand of yuan in bonus money?

This furious response was immediately taken down, yet the screenshot was saved and shared. This sparked a heated discussion online:

“This is what they call the demographic dividend. You quit that job? Someone else will always take your place. You refuse to work overtime? Someone else will always do it!”

“Don’t ask why young people don’t have children, they’ve lost their libido after working too much. Even if they did have children, they wouldn’t have time to raise them. Push a bit more and we’re dead.”

“Your superior won’t ask you to work overtime. They’ll only give you assignments on Friday, tell you to get some rest on the weekend, take your time, and make sure everything gets done before Monday.”

“The worst is overtime with no pay. I don’t remember the last time I had the luxury to leave my office on time.”

“Not getting married or having children is the most silent protest from young people.”

“Our predecessors fought with their blood for the eight-hour workday. Now it’s going to be buried in our generation.”

Tencent responded quickly. The project manager sent out a public reply saying that he understood Zhang’s reaction considering his friend just passed away, and that a follow-up was already in preparation. Also according to Zhang, some supervisors contacted him and admitted this reward was problematic. But he didn’t feel convinced at all: After he sent that message, his development team was discussing ways to meet deadlines as usual.

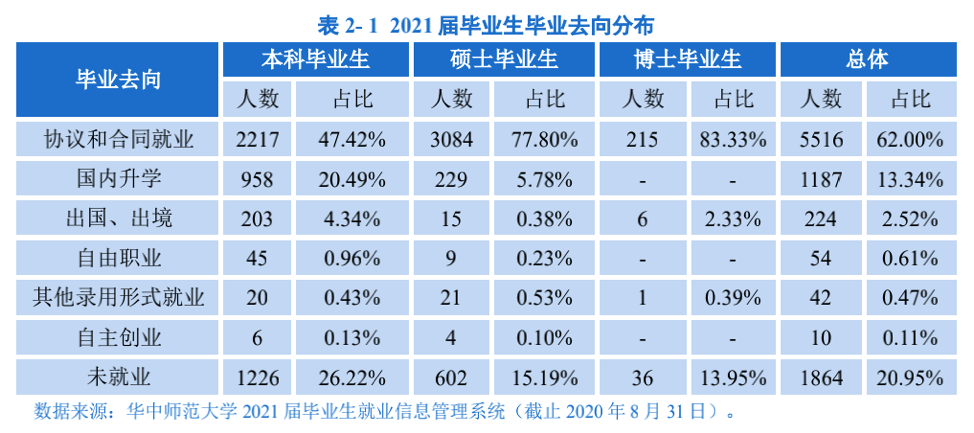

Unemployment Rate for a University’s Graduates Near 21%

Central China Normal University revealed data about graduates’ employment in a report. Bachelors degree graduates there have a “non-employment rate” (未就业率) as high as 26.22%, masters graduates 15.19%, and doctoral graduates 13.95%. The overall rate is 20.95%.

The three biggest reasons listed for unemployment are more interesting: preparation for entrance exams for further studies, preparation for the civil service exams, and still looking for a job. When the demography in China leaves young people with fewer chances, their reasonable choice is to enter the system or just “lie flat”, and since “lie flat” seems to be a risky option, it’s natural to try to be part of the state apparatus in order to enjoy a stable, if not better life. Nevertheless, even civil servants’ welfare was in danger among a context of economic downtrend.

English publications

Xuzhou mother: Video of chained woman in hut outrages China internet

“A video of a Chinese mother of eight children locked up in a village hut with a chain around her neck has sparked outrage and shock in China.” (BBC, January 31)

Also see: Mother of Eight Found Chained Up in Shed Next to Family Home in Xuzhou

“A TikTok video showing a mother of eight living in a small hut with an iron chain around her neck has sent shockwaves across Chinese social media. According to local authorities, the woman is suffering from mental illness and is currently receiving care. But many netizens are still waiting for answers.” (What’s on Weibo, January 29)

For Chinese Workers in Indonesia, No Pay, No Passports, No Way Home

“In March 2021, Zhang Qiang, Zhang Zhenjie, Wei Pengjie, Guo Peiyang, and Tian Mingxin left for Indonesia on business visas through an outsourcing company. […] The five workers soon realized they were being paid far less than had been promised, in addition to several other irregularities. When they decided to quit and return to China in June, they realized they had no passports. […] Desperate to return home, the five men approached traffickers to smuggle them out of Indonesia and back home to China.” (Sixth Tone, January 9)

“New book edited by Darren Byler, Ivan Franceschini, and Nicholas Loubere is now available for free download from ANU Press. The volume aims to document and analyse what is happening in Xinjiang, as well as to propose action.” (Made in China, January 24)

Folding Beijing: A Covid Case Reveals Poverty, Pain in China’s Capital

“Beijing’s glaring wealth inequality became the talk of the nation after a chart comparing two coronavirus patients’ daily itineraries went viral last week. One patient lived a life of sheer luxury, while the other worked over 30 odd jobs over the course of two weeks, all in the wee hours of the night, while living in one of the capital’s poorest neighborhoods. Subsequent reporting revealed the second patient to be Yue Zongxian, a 44-year-old fisherman from Shandong, who had gone to Beijing to petition for help in the search for his missing son. What began as a story of wealth inequality quickly grew to encompass the forces that tear impoverished families apart and the official malfeasance that prevents their reunion. Yuen Ye and Ding Yining of Sixth Tone translated the contact tracing chart that went viral.” (China Digital Times, January 25)

Chinese Economist Banned From Weibo After Baby Subsidy Call

“A well-known Chinese economist was banned from social media platform Weibo days after posting comments calling on the central bank to print $315 billion a year to pay for subsidies to encourage births.” (Bloomberg, January 13)

Free the Fujian Six! Open Letter from a Young Maoist Awaiting Prison

“A letter released on January 4th, 2022, by Maoist writer Yu Yixun (余宜勋), announced the news of his formal arrest and the sentencing of five other young leftists based in Fujian who were arrested last spring.” (Chuang, January 10)

Down and Out in China’ Rust Belt

“Paupers’ Paradise has become a haven for laid-off workers, grifters, and misfits in China’s industrial northeast.” (Sixth Tone, January 18)

Previous Monthly News Highlights

Fake Capital, Persecuted Speculators & Exploited Enterprises: News Highlights, December 2021

Notes

- A large majority of delivery workers are rural migrants.

- It should be noted that this group founded their action on a premise: Ultimately all social relations and issues must be addressed within the legal system for “calibration and resolution.” (所有的社会关系、社会问题,最终都必须落实到法律制度的层面去调整、去解决。) Legal research may help us understand the means through which enterprises are used to consolidate power relations involving delivery workers, but communists cannot rely on the law to provide a basis for anything but narrow reforms to the kinds of labor relationship that face delivery drivers. This analysis can also be understood as showing the inherent limits of even that type of legal agitation.