This post is the first in a series of monthly summaries of highlights from Chinese-language news and social media, offering some analysis of economic trends and the changing character of class struggle in China. Through these posts, we hope to give English readers a broader sample of the discussions taking place across the linguistic and digital divide. In addition, we recommend a few recent English-language publications at the end. (If you notice anything major that we missed, please contact as chuangcn@riseup.net and we can add it to next month’s post.)

Highlights from Chinese News and Social Media, December 2021

Women’s Rights Law Sees Tepid Reforms

China’s Women’s Rights and Interests Protection Law is undergoing a round of amendments, the first major changes to the law in 18 years. These cover a range of issues, from increasing protections against employment discrimination, to allowing women to demand payment for housework as compensation during divorce proceedings, to strengthening language prohibiting sexual harassment.

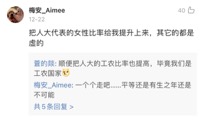

The state is introducing these minor reforms after six years of imprisoning feminists, dismantling their organizations, and attempting to silence their voices—from the 2015 arrests of the Feminist Five, to the harassment and eventual closure of women workers media platform Chili Tribe in 2019, to this September’s arrest for “subversion” of journalist Huang Xueqin, co-founder of China’s #MeToo movement—and the state’s ongoing harassment of anyone suspected of ties to these networks. Meanwhile, the 2022 World Inequality Report has just revealed that China was the only place where women’s share of total labor income actually declined since 1990. In this context, we can interpret the women’s law amendments as similar to the 2017 introduction of “women-only” subway cars in exemplifying how “the state represses self-organised activity and recuperates some of the demands with an intention to undermine further collective action.” Such efforts at recuperation, however, run the risk of helping to spread the struggle over gender and women’s power from narrow activist circles into the broader populace.

Reactions on social media have been mixed. One said, “Actually we have lots of good policies, but it’s for nothing if they aren’t implemented.” One advocated “Parental leave for both women and men! Women’s opportunities for jobs must be guaranteed…” Some even said, “I won’t believe this is in good faith until the ratio of women to men representatives [in the People’s Congress] increases.”

Also see: China contemplates better laws to promote gender equality, but remains hostile to ‘radical’ feminist campaigns—“New draft laws intended to protect women’s rights at home, in the workplace, and on the internet, have brought good news at the end of a bad year for feminists in China, but the men who run the government really don’t want anyone telling them what to do” (SupChina, December 22).

No Lying Flat at Evergrande

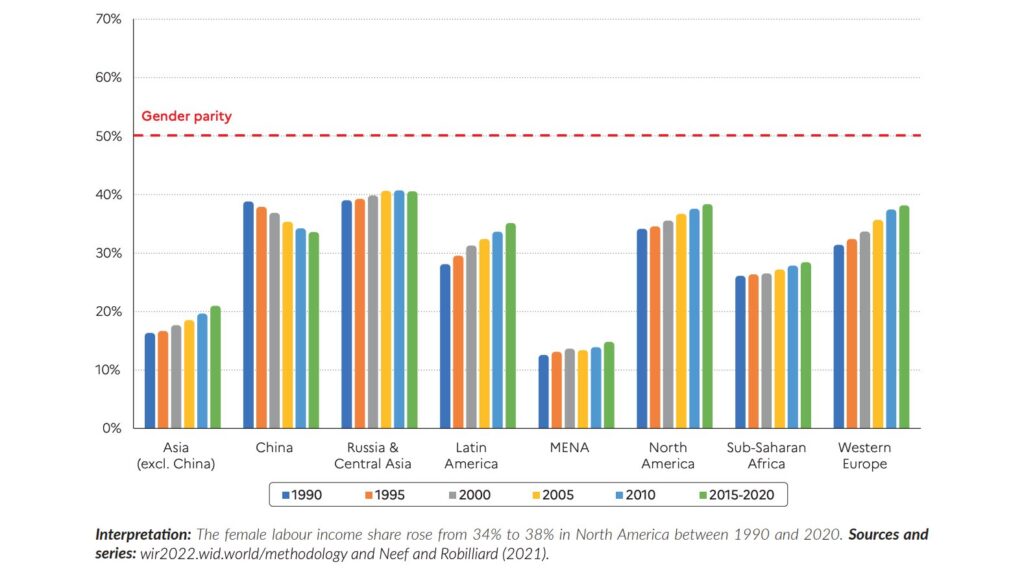

On December 26th, Evergrande chairman Hui Ka Yan announced that he will not allow any employee to “lie flat” at his massively indebted property development firm, now that over 90% of the company’s projects have resumed operations.

“Lying flat” became a viral phrase among Chinese netizens this year, in a rejection of grueling working hours, and of work in general. Here, Hui turns it the term against workers in an open threat. The statement comes at a time when there have been reports of strikes and protests against unpaid wages at Evergrande. There were four reports just within the past week — from Hunan, Guangxi, Shanxi and Yunnan — according to a collection from Hong Kong news outlet HK01. There are plenty of reasons why “lying flat” became such a phenomenon this year. For one, working hours among employed people reached record highs, peaking in the month of October, according to official stats. Average weekly working hours among employed persons hit 48.6 hours in October of this year, the highest figure on record in nearly two decades, according to records from the National Bureau of Statistics:

Entrepreneurs Exempted from Real Estate Tax

Back in October China pushed forward a pilot project for real estate tax reform, and now a new detail has emerged: non-residential property will be exempt, since “companies’ production should not be affected” by any new taxes. This gives a better sense of what many of the “common prosperity” initiatives currently being promoted by the party leadership and circulated in the foreign press are most likely to look like once translated into concrete policies: business will be given room to breathe.

Meanwhile, the head of Shenzhen real estate speculation group Shenfangli (深房理) appeared on Douyin (the mainland China version of Tiktok), in a stream titled “Shenzhen 2022: veni, vidi, vici” after members of this group were arrested for speculation earlier this year. The state serves up a slap on the wrist, but not long after, capital is left to go about its business. Again, the deflated reality of the widely-publicized crackdown on the real estate sector demonstrates the delicate balance the state must strike between stability and speculation.

Frustration at Xi’an’s Pandemic Restrictions

Xi’an in Shaanxi Province has been hit the worst by the latest wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. With 811 confirmed cases through the month of December, its new daily cases make up almost 100% of cases in the nation as a whole. Though tough restrictions were to be expected in case of such an outbreak, it seems that many ordinary people have nonetheless found them excessive. On December 27th, when the Xi’an press conference on the pandemic was broadcast live, many locals rushed to the online platform hosting the broadcast and repeatedly commented, “please allow us to buy groceries” (请安排小区买菜), implying that the lockdown was so severe that grocery deliveries to apartment buildings could not be guaranteed by either volunteers or the government. Such comments were too sensitive for online censors, with at least one platform simply shutting off the entire comments section.

More evidence of the lockdown’s particularly strict nature can by seen in this notice in a residential building, prohibiting residents from using the elevators unless they are going to do COVID tests.

Gotta Find a Job… for Your Parents!

Boss Zhipin (Boss直聘 or “BZ”), an online job recruitment platform, just rolled out a new series of advertisements produced in collaboration with other companies and centered on the hashtag #helpmomanddadfindagoodjob (帮爸妈找个好工作). Some of the posters, where parents are clearly depicted middle-aged or elderly, have more explicit slogans: like, “Looking for a job turns out to be as easy as shopping,” and “Work again like when you were young.”

One of BZ’s promotional pieces, titled “For my early retirement, I found a new job for my old dad,” includes this touching anecdote: “At first I couldn’t understand why [my parents], already out of the bitter cycle of work, would be longing to return to it. But then my father sat up in a serious posture, thought for a moment, and said, with the tone of a newscaster, ‘Working makes me happy.’ My mother just smiled and nodded with enchantment.”

While the policy debate surrounding postponement of the official retirement age—driven by China’s demographic crisis—has yet to be settled, companies seem to be ready for a new wave of employment for seniors.

Financial Regulators to Widen Split between Mainland and Hong Kong?

On December 17th, the Chinese Securities Regulatory Commission published a new rule intended to stifle the influx of “fake foreign capital” (假外资). The Commission said that some mainland investors have set up stock accounts in Hong Kong and are using them to trade on the domestic stock market. This “fake foreign capital” could undermine the goal of attracting legitimate foreign capital to the mainland, the Commission said.

The crackdown on this common practice suggests renewed fears about capital flight. A commentary in the People’s Daily, published just after the Commission’s move, seems to confirm this, saying that Beijing is nervous about controlling turbulence in the economy and therefore aims to prevent “the massive inflow and outflow of foreign capital.”

Union Newspaper Goes to Bat for Businesses

On December 21st, The Workers’ Daily (工人日报), official newspaper of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), published an editorial calling on local governments to stop “cutting the chives” of small and medium enterprises (割中小企业的韭菜) by charging them excessive fines, fees and taxes.1 The editorial cited the case of Bazhou, a county-level city in Hebei Province, whose government collected more than 47 million yuan (US$7.4 million) by excessively fining local enterprises. The editorial trumpeted that small and medium enterprises are the engine (主力军) of the national economy, saying that they carry an “overly heavy burden” from rising costs and the pandemic. Lots of ink spilled in defense of business, but not a single word about workers were mentioned anywhere in the article. But this is typical behavior from China’s toothless state-run union.

Decent Housing for Delivery Workers in Shanghai?

A “youth community” (青年社区)—a term for modern budget apartment buildings—in Shanghai went viral this month after it boasted that its tenants were mainly hotel staff, restaurant workers, and food and parcel delivery workers who slept in rooms priced at just 1,000 yuan (US $157) “per bed” per month. The article, initially posted on Youth Daily (青年日报), was attacked by social media users. One of them, pictured below, was quick to point out that renting out a bunk for a 1,000 yuan in a four-person room was against local regulations. Another, also pictured below, called it a “total rip-off” to set the price by bed. Another comment from another local newspaper suggested that these “rooms” were just another form of “collective dormitory” (集体宿舍). In the end, Youth Daily did nothing but underscore how one of China’s most expensive cities is barely livable for the people who make it run.

Economist Advises Young Workers against Wasting Time on Commuting

Economist Guan Qingyou commented on The Boss’s Broadcast (老板联播) that young employees should not waste so much time commuting. “Why not rent a place close to the office, and instead spend more time investing in yourself?” Netizens grilled Guan on social media for being so out of touch with the reality of the average working person. In one Weibo post sharing Guan’s video, a top-rated comment read “What, so I should take my 2000 yuan salary and rent a 3000 yuan apartment?” while another said “Is this guy sick?”

It’s not the first time Guan has made such remarks. In June, he advised young people in first-tier cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen) not to make any investments before they had saved up enough money for an initial deposit of one million yuan (US$156,000). It should come as no surprise that Guan make’s these ridiculous suggestions because he’s rich. This guy is also the co-founder of Real Capital (an investment fund), the independent director of multiple companies, and a former high level executive in Minsheng Securities.

Good Vibes Only — “The Unkillable People of Shijiazhuang”

Update: The video has been taken down from Bilibili, we can only assume in response to the flood of negative comments documented below. It’s been archived on Youtube by China Digital Times (without the original comments).

Over the past few years, the Communist Youth League has sought to justify its continued existence in an age of crackdowns on “aristocratic bureaucratism” by repeatedly intervening in popular culture. In 2018 it criticized “low moral values” in Chinese rap music, resulting in tighter state controls over the fledgling genre and cancellation of the TV show that had begun to popularize it, Rap in China. Now many of the rap songs still permitted on Chinese music platforms are modeled on earlier, less successful but patriotic tracks produced by the League itself.

More recently, the League has been helping rock bands to re-record their songs, some of them over ten years old, to replace politically questionable and “negative” lyrics with “positive” ones. “Positive energy” (正能量) has been promoted throughout Xi Jinping’s tenure as president, starting with the Central Forum on Arts and Literature in October 2013. As the China Media Project explains, this term (adopted that year from a British psychology book) now “generally refers to the need for uplifting messages as opposed to critical or negative ones – and particularly the need for content that puts the Party and government in a positive light.” Anyone who has lived in China the past decade can testify to the term’s gradual diffusion throughout all spheres of life and its insidious deployment by parents, teachers and employers—not to mention do-gooders from the Communist Youth League.

The latest victim of these good vibes is the indie rock band Omnipotent Youth Society (万能青年旅店), whose 2010 hit “Kill That Person from Shijiazhuang” (杀死那个石家庄人) was just re-released under the title “Unkillable People of Shijiazhuang” (杀不死的石家庄人), thanks to the Youth League’s branch in Hebei Province. The original song tells the story of a factory worker in the rust-belt city of Shijizhuang throughout thirty years of China’s capitalist transition from the 1980s to the 2000s, with a tone of somber realism. The new version, as the title implies, turns that frown upside down by changing lyrics such as: “Buy a fake gun with counterfeit money / Defend her life / Until the skyscraper collapses / Night is looming over the North China Plain / Melancholy suffusing her face” (用一张假钞/买一把假枪/保卫她的生活/直到大厦崩塌/夜幕覆盖华北平原/忧伤浸透她的脸) to: “Rusted hands of the clock / rotating with effort / Let’s light up a bonfire with our dreams / and stride with our heads high / Dawn is coming to the North China Plain again / Let’s pull our scattered faith back together” (锈蚀的指针/奋力地旋转/燃起梦的篝火/昂首迈步进发/黎明再临华北平原/重拾散落的信念).

After the new version was posted on the Chinese video platform Bilibili, the comments were soon dominated by criticism and sarcastic remarks:

Even the singer of this version took the risk of responding to the criticism: “I’m sorry, I didn’t put enough thought into this. I was just thinking this would be a simple cooperation with the Youth League to produce a song with positive lyrics. Now I’ve tendered my resignation from further work with them. Sincere apologies. ”

English publications

China to equip and train Solomon Islands police after anti-China unrest

“Pacific Island nation to host six Chinese officers as well as receiving shields, helmets and batons, says government.” (Guardian, December 24)

What is happening in Xinjiang as 2021 draws to a close?

“A Q&A with Darren Byler, author of a new book on China’s oppressive policies against Uyghurs and other Muslims in western China.” (SupChina, December 16)

“China’s industrial demand for soymeal is ravaging Brazil’s ecology, putting its supply chains at odds with its domestic ‘ecological civilization’ program. What is the ecological calculus of boosting afforestation at home while driving deforestation abroad?” (Lausan, December 15)

China’s Couriers Say Bosses Took Their Raise

“A pay increase for couriers, presented as a ‘common prosperity’ income equality package, has been delivered to wrong address.” (Sixth Tone, November 3)

Chinese Province Offers $31,000 Baby Loans to Counter Shrinking Population

“Jilin province in northeast China will support banks to provide up to 200,000 yuan ($31,400) of “marriage and birth consumer loans” to married couples.” (Bloomberg, December 24)

Taiwan chip industry emerges as battlefront in U.S.-China showdown

“The island dominates production of the chips that power almost all advanced civilian and military technologies. That leaves the U.S. and Chinese economies extremely reliant on plants that would be in the line of fire in an attack on Taiwan.” (Reuters, December 27)

Chuang on China, Communism, and Social Contagion

Audio interview on the Antifada, Cinder Bloc and History Against Misery podcasts (December 8)

Reflections on Social Contagion

Panel discussion on our new book with Aminda Smith, Kevin Lin, Promise Li, Eli Friedman and Sonali Gupta (December 5)

Notes

- “Cutting chives” means something similar to “exploitation”: taking advantage of someone, but in way deemed ridiculous or irresponsible. In contrast with the class sense of “exploitation” (剥削, associated with the Marxist sense), the term “cutting chives” originally referred to the plight of individual, inexperienced investors in the stock market having their “chives” (profit) cut into by corporate capital and changing state policies.