CW: violence, suicide

Two months have passed since Mr. Hu strapped explosives to his body and walked into a local government building in his home village in southern China. Hu took his own life and those of five others in the building with him on a Monday morning as officials were opening the week’s affairs. The Panyu incident was not named an act of domestic terrorism by the state or domestic press, but it was easily the most deadly attack on a government entity in many years, stretching back perhaps to the last major reported strikes by assailants in Xinjiang, like the Sogan colliery attack in 2015 that left sixteen people dead, including six police officers, or the 2016 car bombing of a government building in Karakax county, that killed one person and left the four attackers dead. The Panyu incident went largely unnoticed in the foreign press, and domestic coverage was strictly limited, likely due to heightened government nervousness as the Chinese Communist Party prepares to celebrate the 100th anniversary of its founding in July. Nothing must disrupt the narrative that Xi Jinping and the CCP represent the communist legacy and future of the world’s most populous nation and second largest economy.

Obviously, only a small number of suicides in China are direct attacks on the state, or clearly made in social protest. But some are, as the words of the dead in the cases below clearly show. The nation already had a severe suicide problem, though its nature has often been misunderstood. Suicide in general, by definition, always has a social dimension, even if most media coverage doesn’t acknowledge it. For decades China has been infamous for having one of the highest suicide rates in the world. In 2006, a study funded by the central government acknowledged that China is the only country in the world where the suicide rate is higher for women than for men, noted in a book on suicide in China published just last year. The study said suicide was worst among rural women, with 160,000 suicide deaths each year—half of all recorded women suicides in the world. Suicide rates among rural women have declined, but that is likely due to urban migration more than any other factor. The author, Li Jianjun, blamed cultural “traditional attitudes,” or the allegedly “impetuous” nature of many rural women, playing down obvious factors like extreme poverty, subjugation of women in male-dominated households, or the heavy burdens of domestic labor, childrearing and general social reproduction upon which China’s economic growth has been founded. Tracking the number of suicides committed by corrupt officials facing prison or execution has become something of a sport for foreign “China watchers,” believing that it may be a sign of regime instability, but the dire choices left to China’s proletariat are not only a sign of immiseration and desperation, but also expressions of righteous public anger with nowhere else to go.

The Panyu incident was just one of several recently reported suicides against injustice and hopelessness that illustrate the real social tensions in China today, flying in the face of the CCP’s daily proclamations of confidence, legitimacy and strength in the run up to the centennial. Below, we recount a few of these cases of desperation and the social media discussion around them.

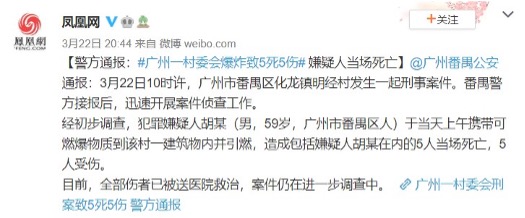

Mr. Hu of Mingjing Village, Panyu District, Guangzhou (广州市番禺区化龙镇明经村)

On the morning of March 22nd, when local officials were said to be having an important meeting, a man surnamed Hu walked into the Mingjing Village Committee Building, his body strapped with explosives improvised from construction materials. The blast rang out at around 10am and killed five people in the building, including Mr. Hu, injuring five more. An edited video circulated by state media in the aftermath showed broken furniture and other debris scattered throughout a concrete building with blown-out windows. But the full version of the same video that circulated like wildfire online contained footage of the blood-stained walls of a state hall of power.

We may never get to hear the real story of Hu, or what exactly motivated him to take his life and those of others that morning. Panyu police declared the incident a “criminal act” within hours of the blast and had named Hu as the suspect before the end of the day. It will likely be treated as an open and shut case, and we will not hear anything from Hu’s friends or family members, who are likely being watched closely by authorities.

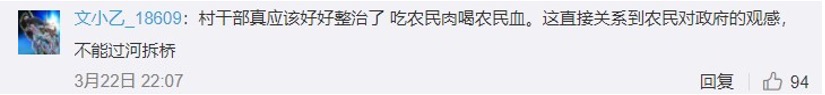

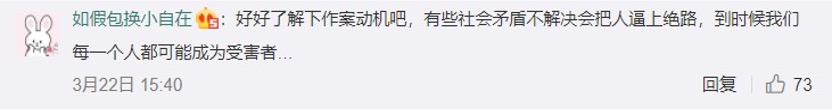

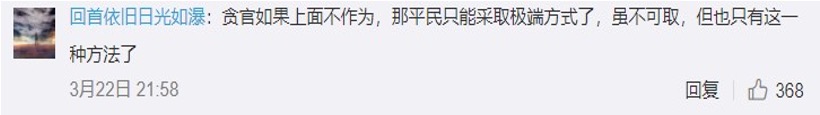

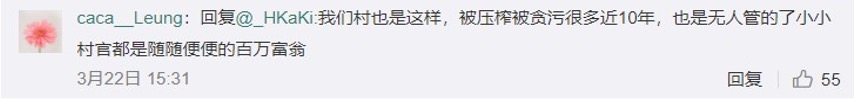

But social media users, while generally shocked by the violence, were not at all shocked by the likely cause: corruption. A wave of responses to the blast, presented in detail below, showed that the explosion in Mingjing was likely a reaction to years of blatant powerplays by local government officials aimed at swindling locals and forcing them off their land. From these compiled responses, it’s clear that the average Chinese netizen knows that the cycle of abuse is rooted in the economic game played by officials and land developers, where local governments sell land for property developments, forcing off those who once lived there for chump change, while officials and developers make a killing.

The most common theory circulated online was that Hu had been involved in a broader land dispute with the local village committee, which had repossessed some 270 acres of collectively-owned land,1 converting it to state-ownership so that it could be placed on the market. The land was sold to a Shanghai-based developer last year in a US $1.2 billion deal, as a scheme to create a tourist attraction. The land sale story, and the tales of violence that followed, have been all too common in China since the capitalist transition spread to the sphere of land ownership and became more centered on real estate over the past two decades. Land is, after all, a major source of tax revenue and credit collateral for local governments. Localities have been relying on land sales revenue even more heavily after the central government declared a range of tax cuts to fuel the COVID-19 recovery, with land sales accounting for more than half of national combined tax revenue in 2020.

Land or Death

Forcing bad terms on locals to squeeze the most out of land deals has often led to violent conflict. The now defunct Wickedonna blog project, which recorded 70,000 reports of protest in China between 2013 and 2016, logged 726 cases involving home demolition and land sales in the year 2015 alone. Tales of desperation and suicide over land disputes are not difficult to find, even collective suicide. In 2016, five men and four women villagers in Fujian drank deadly pesticide in front of the Longyan city government building, in a gesture of suicide, though none appear to have died. And of course the repossession of collectively owned land sat at the heart of the infamous Wukan uprising, a protracted battle between locals and their own village committee between 2011 and 2015.2

Land sales, and land disputes, have indeed continued, though they are obscured from view due to the combined forces of more sophisticated social media censorship, the crackdown on citizen journalist projects like Wickedonna, and a general lack of interest by domestic and foreign press, resulting in the same old story of abuse told over and over again. Despite the novelty of Mr. Hu’s bombing, most foreign media reported on it late, or skipped the story entirely. China pages were instead busy rehashing US-China talks that had occurred a week earlier, or covering the trial of Canadian Michael Kovrig, or other news related to China’s international politics and trade. And in domestic social media, the initially widespread discussion of the Panyu incident was quickly drown out by other daily news as social media algorithms shifted precedence to less sensitive content.

The discussions we did find, however, provided insights into how land grabs are perceived in the public eye. Across Sina Weibo, netizens were quick to offer their sympathies—not to the officials who were killed, but to the alleged bomber. People were quick to compare the situation in their own villages to the assumed corruption in Mingjing, with some going so far as to dream up personal revenge fantasies. Government land grabs are still clearly a very contentious topic, and they’re still a source of simmering distrust towards the state.

It’s difficult to say the exact extent to which sections of China’s population see violence against the state as potentially justified to some degree. The examples we’ve picked from among the flurry of comments about the incidents are the more striking ones, but expressed somewhat common sentiments. On the other hand, some Weibo users seemed baffled that anyone could assume that a mass murderer could have had rational motives. In their confusion, however, these same critics had to ask whether, for a brief moment, the act wasn’t provoked, or in some way deserved, and acknowledge that the bomber might in fact be striking out against petty local bullies.

The diversity of opinions on this incident is significant in its own way. It is difficult to imagine (though time will tell) how Chinese social media might become any more censored in the future, or be made more susceptible to political sculpting. Already, all comments are monitored in real time, by keyword, on the lookout for sensitive events like the bombing incident. Platforms are already influenced by pro-government content produced by algorithms or paid commenters, and anything mildly controversial is outright blocked and deleted by the armies of internet watchdogs paid for by the internet platforms themselves, not to mention the state’s own well-funded internet police. And yet, these diverse, and even dissident, opinions continue to crop up.

A similar phenomenon was visible in response to the Hong Kong protests in 2019. In June of that year, when the summer protest wave had only just begun to gain steam, China’s censorship apparatus clamped down on social media users to control discussion of Hong Kong. But the many supporters of the protests found ways of bypassing censors by using alternate keywords, rotating pictures or other minor hacks savvy netizens use to discuss sensitive issues. Even as the censorship intensified, along with state propaganda, supporters carried on despite being reported by informants. Whether it be Hong Kong, Panyu or any number of events of social import, the question remains: in spite of all the censorship, what is the real distribution of political attitudes across the Chinese population, if people could be asked in an honest fashion under different circumstances of interaction?

The same could be asked, of course, of populations in the United States, South Africa or Argentina, if the media environment were structured differently. After all, political legitimacy has been falling in countries around the world, with protests on the rise. But in Panyu, no doubt, it is clear that the material conditions of development – and the visceral reaction of resistance – will continue to produce an angry response, online and off. People tend to know when they are getting screwed, regardless of who else notices.

Other Cases

Mr. Hu’s case was just one of several high-profile suicide cases by angry or desperate workers this year so far. Just two days after Mr. Hu took his life in Panyu, a 33 year old worker named Wang Long jumped into a blazing steel furnace in Baotou, Inner Mongolia, allegedly after losing 60,000 yuan on the stock market. Wang was working the night shift on March 24, and surveillance video captured him casting aside his safety helmet and gloves before leaping into the molten steel. Social media news and videos claiming that a steel worker had leapt to his death due to high work pressure went viral on social media, forcing Baotou Steel to release a statement claiming that the company was deeply troubled by his death, and that his suicide had nothing to do with his job, and everything to do with his stocks.

The incident at Baotou Steel, a large state-owned enterprise, caused some to connect his death to the plight the hundreds of thousands of state-owned enterprise workers laid off in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Forced onto the labor market, many of them had to pick up new, more difficult and lower paying jobs like truck driving. The memory of those who felt betrayed by the party and left behind by the state lives on to this day, as workers reach retirement age but with none of the benefits they would have enjoyed as retired state-owned enterprise workers, like pensions or fees to cover funeral expenses. Nowhere is this more acute than in China’s Northeast, the country’s largest rustbelt. The latest census figures, released every ten years, show that the three northeastern provinces lost 30 percent of their population between 2010 and 2020.

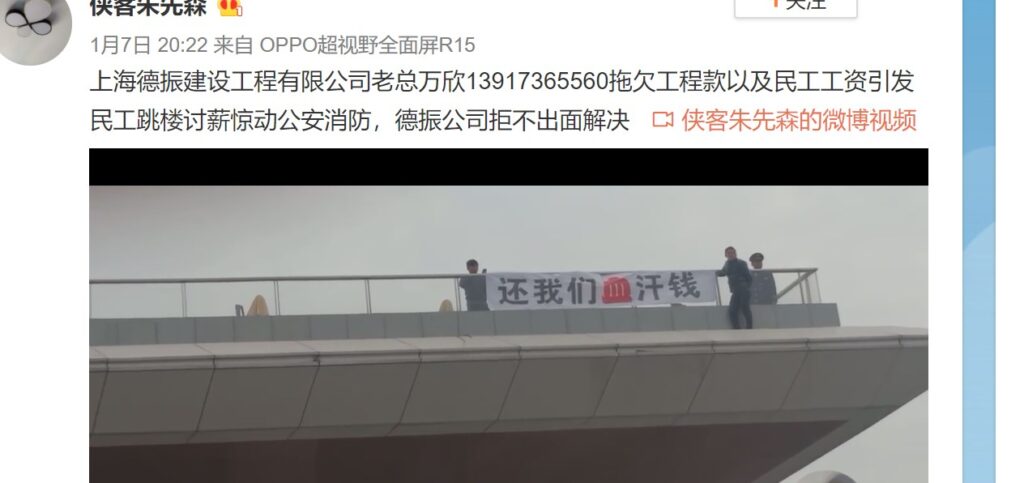

Many will recall the Foxconn suicides that came to light more than a decade ago, where at least 14 men and women workers killed themselves in 2010 alone (revisited extensively in a book released last year). But suicide, and threats thereof, recur throughout multiple industries, especially the construction sector, where workers often threaten to jump in desperate demands for unpaid wages. China Labour Bulletin has documented nine such cases so far this year, recording more than 400 incidents of jumpers over the past 10 years.

Other forms of suicide have taken the form of organized movements or waves, including suicide bombings in Xinjiang and Tibetan self-immolation. Waves of self-immolation have occurred in the Tibetan Autonomous Region and other Tibetan-majority areas for decades. Though exact numbers are unclear, activist organizations say that at least 157 Tibetans have performed self-immolation protests since 2009, with the vast majority resulting in death. But self-immolation is not limited to Tibetans.

In January, a food delivery rider for Ele.me attempted suicide by self-immolation in the city of Taizhou, Jiangsu province, after being denied 5,000 yuan owed to him by the company—equivalent to one month’s pay. The 45-year-old rider, Liu Jin, poured gasoline over his body in front of his company’s food delivery station on 11 January, lighting himself ablaze. Bystanders used fire extinguishers to put out the flames, but Liu was left with second and third degree burns over 80 percent of his body, requiring multiple rounds of surgery. Liu Jin was described as by colleagues simply as an honest man, with no other remarkable characteristics. At the hospital, Liu told his sister “I don’t want to live. I’ve lived enough, I’m exhausted.”

Liu Jin’s sister Liu Peng told reporters that he had left his home town in Yunnan ten years ago, working with a construction team to lay communications cables until it was disbanded three years ago. He then started working in food delivery, hoping to make a bit more money. Like the truck driver Jin Deqiang (discussed below), Liu had heavy family burdens to shoulder. Liu’s wife had contracted a liver disease and could only work odd jobs earning around 1,000 yuan per month. The couple had two daughters, with the eldest (aged 21) having just started working as an apprentice (it is unclear in what industry) and the youngest starting college. Liu Jin regularly sent around 4,000 yuan per month to his family: 1,500 to his youngest, plus 1,000 for rent on their family home and 1,500 for their living expenses. A month before Liu set himself on fire, his mother had fallen ill and he was forced to borrow 2,000 yuan from a colleague. When Liu’s wife rushed to the hospital after his suicide attempt, she had only 400 yuan left in her own bank account. Liu’s sister recounted that the last time she’d seen her brother was over the National Day break in October. “My brother at the time said that after the kids go to school, they had better work hard to earn some money. We all told him at the time to take it easy, and that the whole family would be working hard to help get the kids through school.”

On April 4th, yet another suicide became a point of nationwide discussion, when truck driver Jin Deqiang took his own life after being given a 2,000 yuan fine at a weigh station in Tangshan, Hebei. Police had confiscated Jin’s vehicle and handed him the fine for not having an operational Beidou satellite positioning system – China’s version of GPS. Struggling with debt, low pay and incessant fines, Jin had only 6,000 yuan to his name at the time of his death, according to reports. His wife was unemployed, and with two children and elderly parents to support, Jin was at his wits end. He went to a nearby shop, bought a bottle of pesticide (similar to the land dispute victims, and so many other suicides among the poor), drank it at the weigh station, and was dead before the end of the day.

Before killing himself, Jin sent out a message to a WeChat group of fellow truckers:3

To all my trucker friends across the country, when you read this letter, I will be about 6 hours away from death. I am not even worth 2,000 yuan, and I am speaking for the majority of truck drivers. The video above shows my location. Let me first introduce myself, Jin Deqiang. I’m 51 years old this year and I’ve been in the transport industry for 10 years. Not only did I fail to earn much money, but it’s even destroyed my body. My heart is wrecked, and I have high blood pressure, high blood sugar and high cholesterol. Even with a body in this condition, I have to keep working. Today I am in Fengrun district, where I was detained at a weigh station, saying my Beidou was offline and fining me 2,000 yuan. Tell me how is a driver supposed to know? I feel that I’m not going to live much longer, so I use my death as a warning to the those in the leadership. I want to apologize to my elderly mother most of all. My father died when I was nine years old. That year, my brother was only 12. It was my mother who raised us, and that was a very difficult thing to do. I have seen right through this world’s deceptions and realized that it’s meaningless. I was going to died sooner or late anyway, so now I’m just dying a little earlier. Some people may say that I’m heroic, but everybody has their own opinion. Don’t laugh at the voice memos I left here. My name is Jin Deqiang. My truck number is 1308. Goodbye forever to my son and daughter. After I die, take good care of your grandma and mother. Son, take care of your sister. Don’t be too sad after I’m gone. Be angry, be mad and live your life well. Don’t be a good for nothing like me. Jin Deqiang.

China’s Ministry of Transportation did respond to the incident, saying they would step up supervision of the trucking industry, and in most mainstream media outlets Jin’s death merely sparked a discussion about excessive traffic fines. But the social media discussion mourned the loss of Jin. His suicide note was shared widely among online trucker communities on Weibo, Douyin and Kuaishou, but mentioned only in part in mainstream media accounts.

Just a few days after Jin’s death, on April 12th, a young truck driver from Shandong, surnamed Zhao, slashed his wrists at a weigh station in Qingyuan, Guangdong province, after his truck was detected to be overweight. The trucker, who was identified as belonging to the “post-1990” generation, was carrying industrial metals from Shandong on the east coast to Guangdong in the south, and successfully crossed half a dozen weigh stations, remaining just under the limit for his 50-ton truck. But at a Qingyuan weigh station, Zhao was found to be overweight by just 240 kilograms, and the weigh station slapped Zhao with a 300 yuan (US $46) and had three points deducted from his license. Frustrated, Zhao appealed for a reweigh, but the weigh station refused. Zhao called a complaint hotline, but no one answered. Zhao grabbed a knife and slit open his left forearm and begged the traffic station for a second weighing, to which the finally agreed, and found him to be underweight, at 49.89 tons. News media pictures showed records of Zhao’s interaction with the station, their refusal to reweigh, and a picture of his medical treatment with 14 stitches running down his forearm over the wound.

Suicides like these—where one person throws their own life against the system itself in desperation and anger—will no doubt continue, under the radar, or in the pages of China’s mainstream media. But these social media comments show that many netizens know, and understand, the gravity of a suicide attempt, and exactly where this desperation comes from. It resonates with the desperation they experience in their own lives, recently being articulated in the widespread discourse of neijuan (内卷) or “involution”—the feeling of being trapped in a miserable cycle of exhausting work that is never sufficient to achieve happiness or lasting improvements, but from which no one may opt out without falling into disgrace. They feel it when they complain that life feels like an endless competition with no victors, and they feel it when they dream of the day that’s coming when they will finally win.

But that day never comes. Debts pile up, petitions for help go ignored, remaining options start to dwindle. In a time of involution, when even the smallest reforms seem impossible, all that remains are desperate measures. The media pretends to be baffled, and the state, of course, remains silent. One netizen’s comment on the death of Jin Deqiang perhaps sums it up best:

Notes

- Much of China’s rural land is technically owned collectively by a group of residents, who each have a claim to the revenue if the land is sold. In this case, and in many others, the local government rezoned the land, taking it out of residents’ hands and remunerating them at a low rate to maximize the value of the sale for the state. For more on this process, which has been a key site of struggles for decades, see our article Gleaning the Welfare Fields in our first journal issue.

- For more on Wukan and the dynamics of land disputes, see “Gleaning the Welfare Fields” and “Revisiting the Wukan Uprising of 2011” from the first issue of our journal.

- The original is included here in case it is removed from other websites: 全国卡友你们好,当你们看到这封信时我大概离死亡还有6个小时,我不是不值2000元钱,我是为了广大卡车司机说句话,上面视频是我在的位置。我首先介绍一下我,金德强,今年51岁干运输10年了不但没有挣到多少钱,反落下了一个身病,三高心脏也坏了面对这样的身体也得坚持工作,今天在丰润区超限站被抓说我北斗掉线,罚款2000元请问我们一个司机怎么会知道,我感觉到我也快活不长了,所以我用我的死来换醒领导对这个事情的重示,我的死最对不起的是我年迈的老母亲,我九岁我的父亲就去世了,那年我的哥哥才12岁是我的母亲含心如苦吧我们两个拉扯大,太不容易了。我对人生已经看透了太没有意思了,早晚是死只不过早几年尔已,我死后也许有人说我雄,人的思想不一样不要躲我语音功激。我的名字金德强。车号1308 儿子姑娘们永别了,我死后好好的疼你的奶奶和母亲,儿子照顾你的妹妹。我走后不要过度悲伤。生气赌气把日子过好。别学我窝窝囊囊一辈子。金德强。