Summer in Smoke:

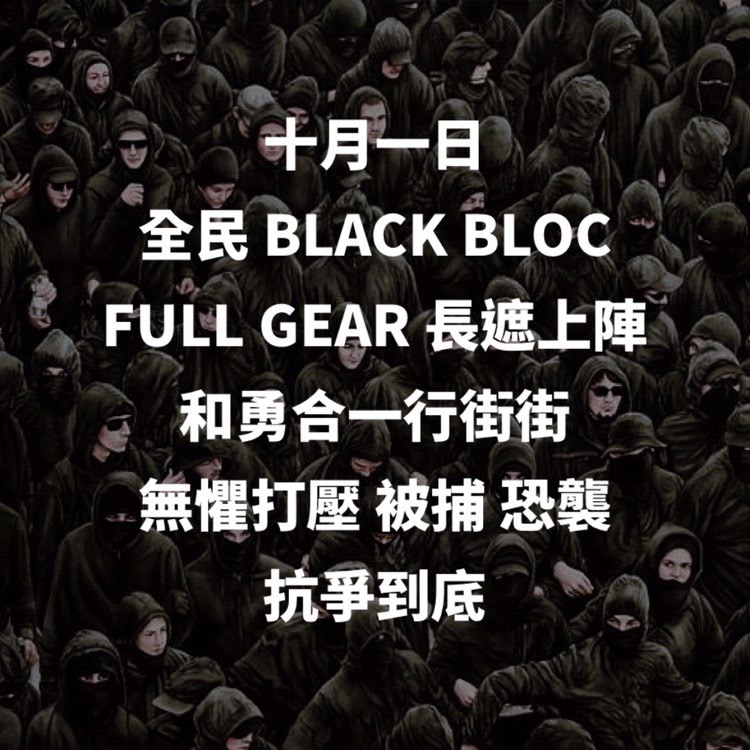

Report from the World’s Biggest Black Block

für Sandra in liebendem Angedenken

It was only a matter of time before it happened. The protesters and the cops both knew it. On October 1st, a teenager was shot point-blank in the chest by police. The bullet missed his heart by approximately three centimeters.

Thousands of Hong Kongers gathered the next evening at a playground to fold paper cranes and wish the young protester a speedy recovery. They held banners saying “stop shooting our children!” and used the flashlights on their smartphones as torches to light up the night. In the center of the playground, a thousand origami cranes spelled out “Hong Kongers, Add oil!”, a Chinese expression which has come to define the movement, meaning roughly: don’t stop, keep going, add fuel to the fire. Within an hour, the protesters were setting up barricades in the streets and throwing molotovs at the nearest police headquarters.

The movement that began as a protest against a proposed extradition agreement with China has now entered its fourth month of unrest, with no end in sight. The bill — now withdrawn — would have granted the Chinese State unprecedented authority to extradite dissidents, criminals, and refugees to be processed in the shadowy court system of the mainland. Coming on the heels of 2012’s Moral and National Education Law and 2014’s Electoral Reform Bill,[i] this amendment was only the latest attempt at slowly dismantling the region’s tenuous political arrangement of “One Country, Two Systems.” With the movement rapidly evolving into widespread resistance against Chinese control, and the Hong Kong government declaring a State of Emergency, the situation has reached a political stalemate, with violence escalating on both sides.

In what follows we lay out a brief timeline of the movement’s defining moments, why tensions are so high in the Pearl River Delta, and what tactical and strategic lessons protesters elsewhere can take from this. We will not evaluate the movement based on its ideology, but instead describe how it has provided the basic arsenal and grammar for the future of struggles against the techno-authoritarian surveillance systems to come.

The first major protest against the extradition bill, 9 June 2019. [Thomas Peter, Reuters]

1 – SAVAGE DISCORD

The first major demonstration against the proposed Extradition Law Amendment Bill took place on June 9, with more than a million people taking the streets. On June 15, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam announced that the bill had been “suspended,” a move widely perceived as a political ruse, buying time for Hong Kong’s Legislative Council to pass the bill quietly at a later date.

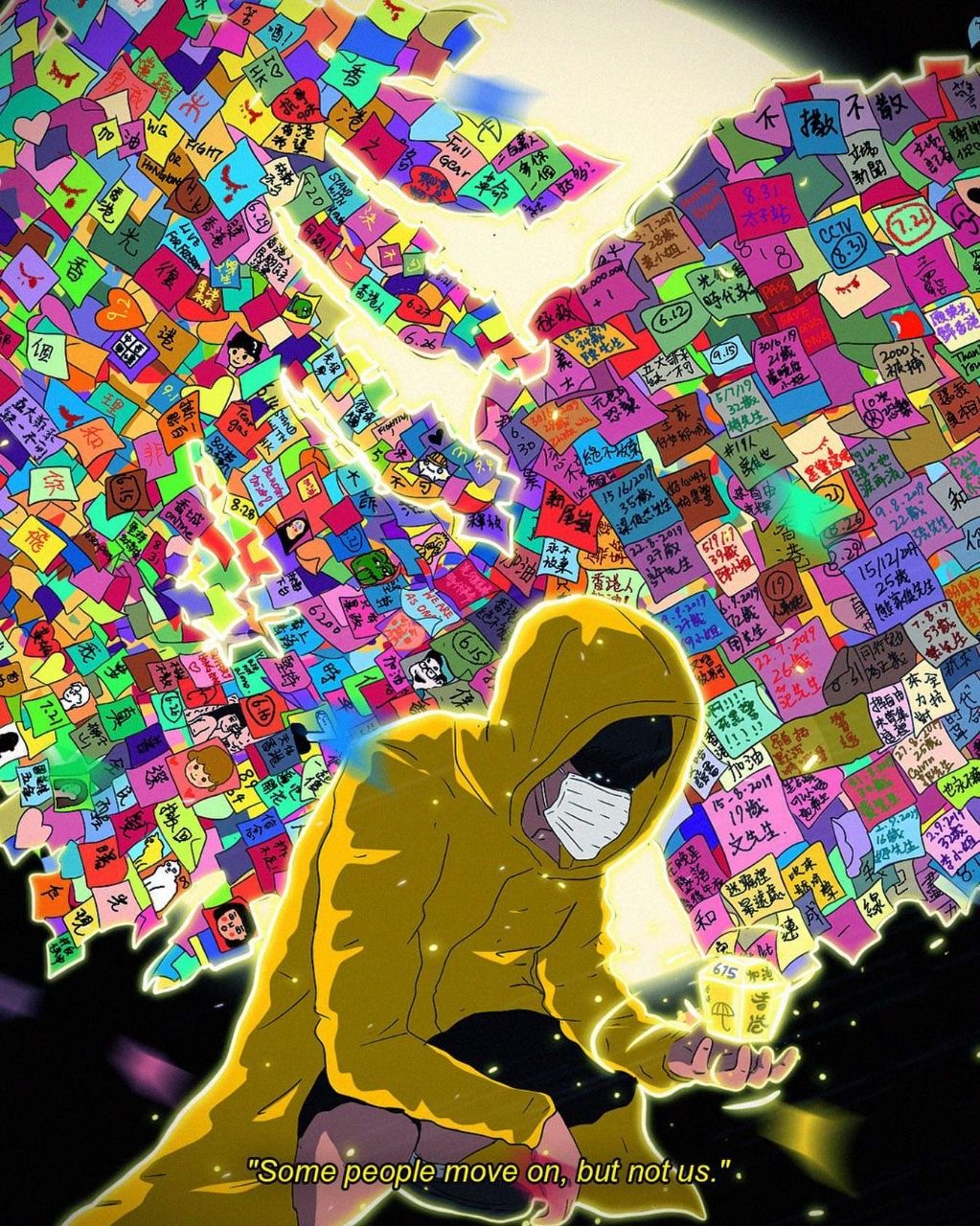

A few hours after the announcement, a young man in a bright yellow rain jacket, his face concealed under a surgical mask and sunglasses, climbed the bamboo scaffolding of a famous shopping mall in the city’s central business district. A few days earlier, a peaceful demonstration at the mall was characterized by Lam as a riot. When the man unfurled banners from the rooftop demanding the government retract its designation of protesters as rioters and release those arrested, it became clear the movement was turning into something much bigger than a demand to withdraw the bill.

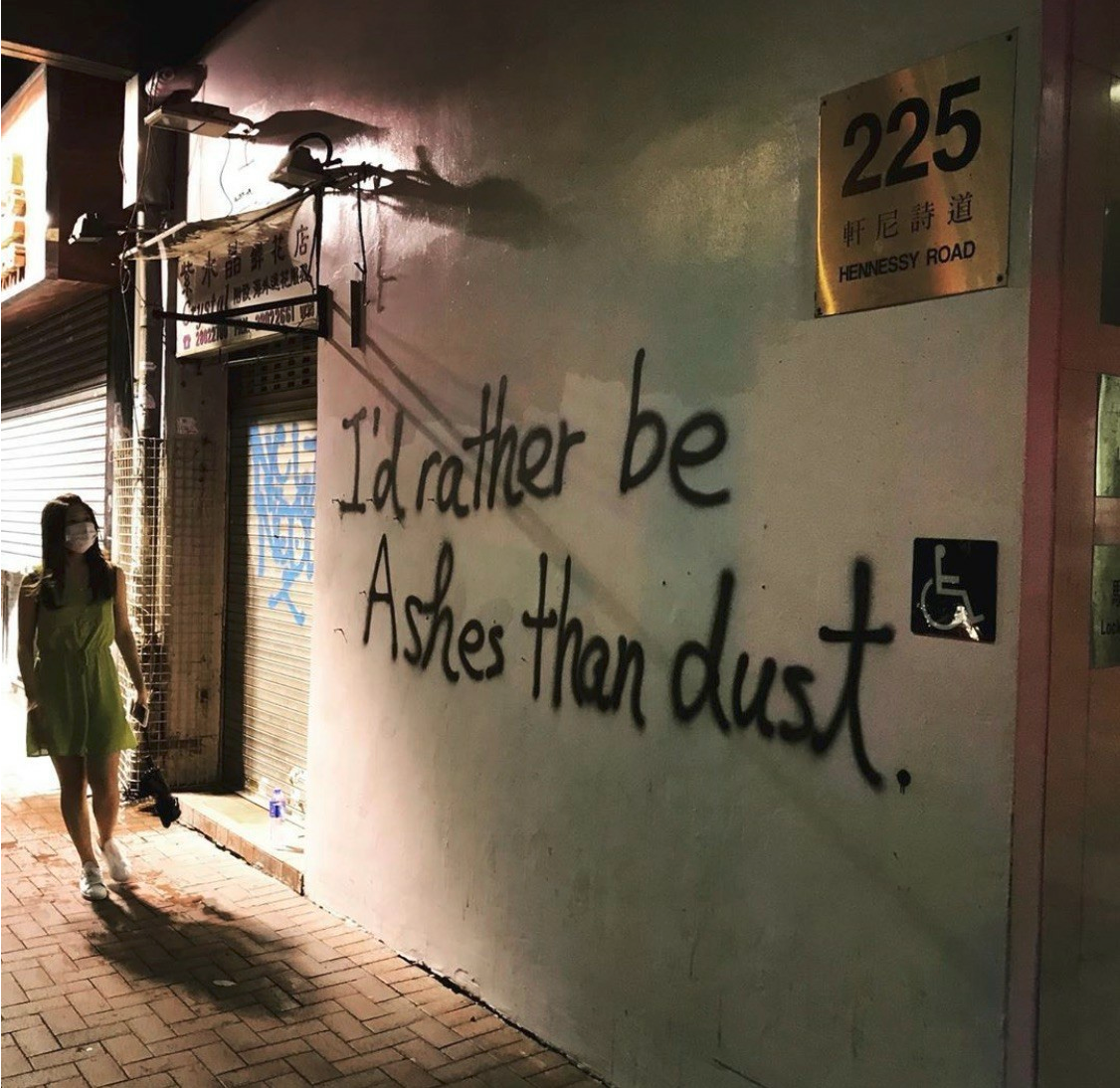

Thousands live streamed the stand-off, as police negotiators and members of parliament tried to persuade the man to step down. He kept his back to the cameras, displaying the message painted on his jacket: “Carrie Lam is killing Hong Kong.” After a grueling five hours, the man jumped from the seven story building, intentionally missing the inflatable cushion firefighters had set below. His anonymity allowed everyone to see themselves reflected in his anguish. Marco Leung Ling-Kit, the man in the yellow rain jacket, became the first martyr of the protests. The movement was now no longer about the bill, but about Hong Kong’s absent future. Millions took the streets the next day to fight and grieve, adopting black as their uniform-in-mourning. Headlines tallied the number of protesters that day: “Two Million Plus One.”

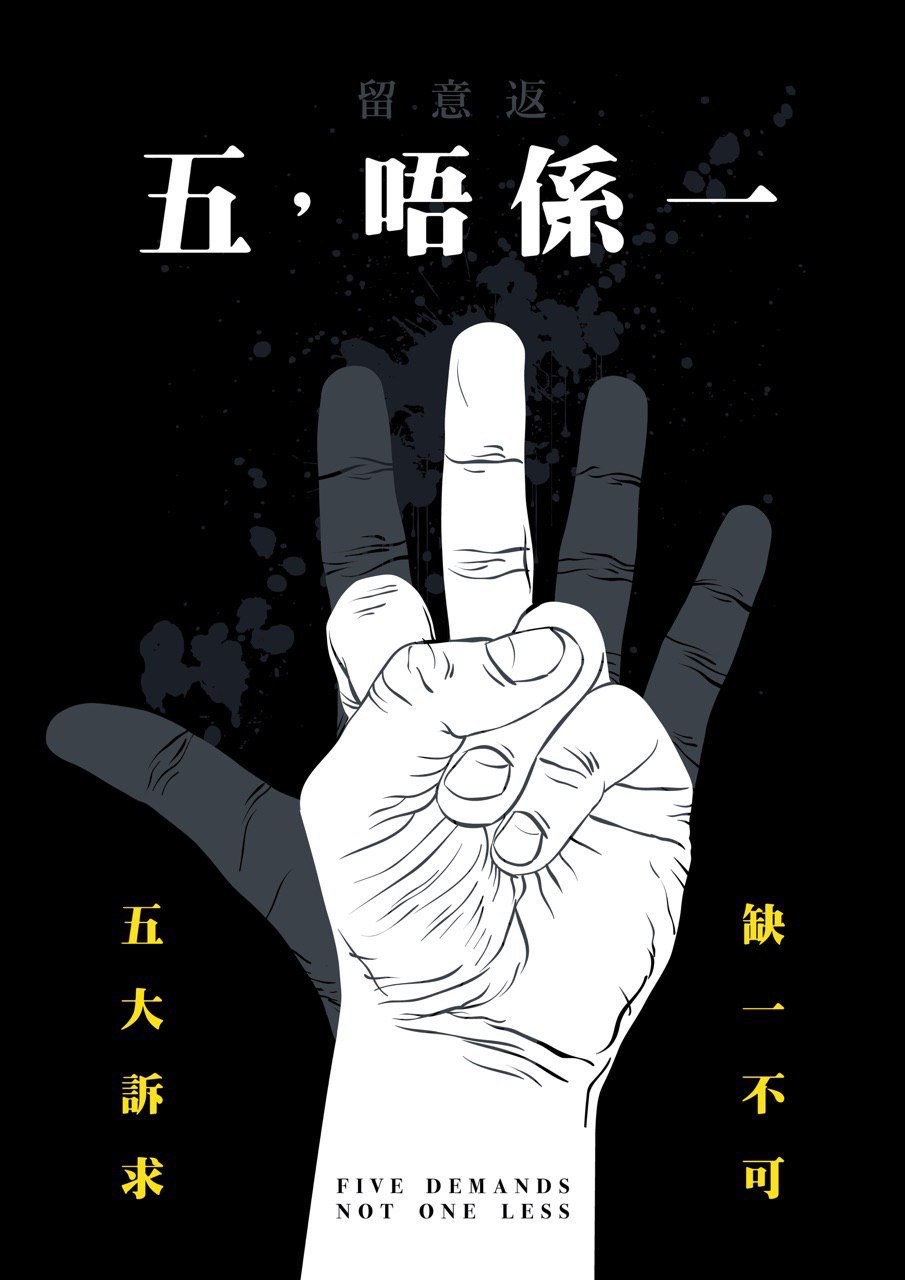

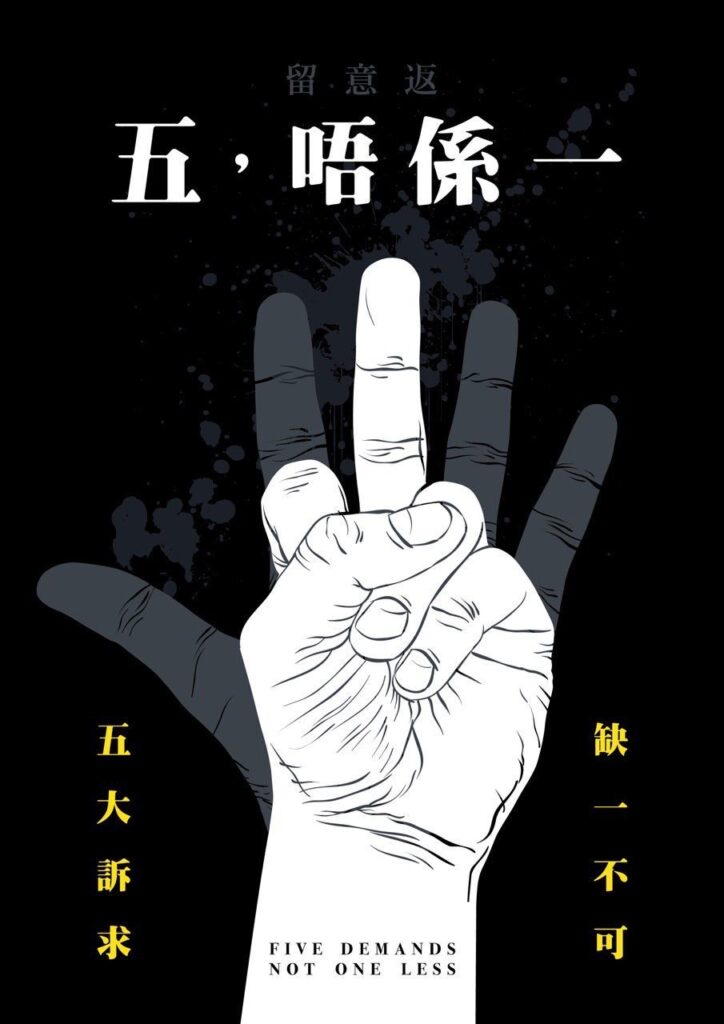

With Marco Leung’s final testament as a baseline, the movement consolidated around five core demands: 1) the formal withdrawal of the extradition bill, 2) the retraction of the legal classification of protests as “riots”, 3) the immediate release of all arrestees, 4) an independent investigation into the Hong Kong Police Force, and 5) universal suffrage.

Protestors storm the Legislative Council, July 1st, 2019. [Sam Tsang, SCMP]

Three more suicides, on June 29th, June 30th, and July 3rd were punctuated by the spectacular storming of the Legislative Council on July 1st. Faced with a leaderless, diffuse struggle across every corner of the city, the police grew desperate. By mid-July they were tear gassing train stations, pepper-spraying and clubbing anyone wearing black, and indiscriminately arresting both children and the elderly. When neighborhoods began resembling police occupations, residents started coming down from their apartments to heckle the police, calling them “terrorists” and “criminals.” Some began sharing on Telegram the gate codes to their apartments to provide shelter to youth fleeing the police. On July 21, a hundred suspected triads, wearing masks and wielding lead pipes, attacked protesters at a Metro station on the outskirts of the city. Protesters were trapped in the station after the City canceled all trains leaving the demonstration. Police, for the first time, were nowhere to be found. The government was collaborating with the gangs to suppress the movement.

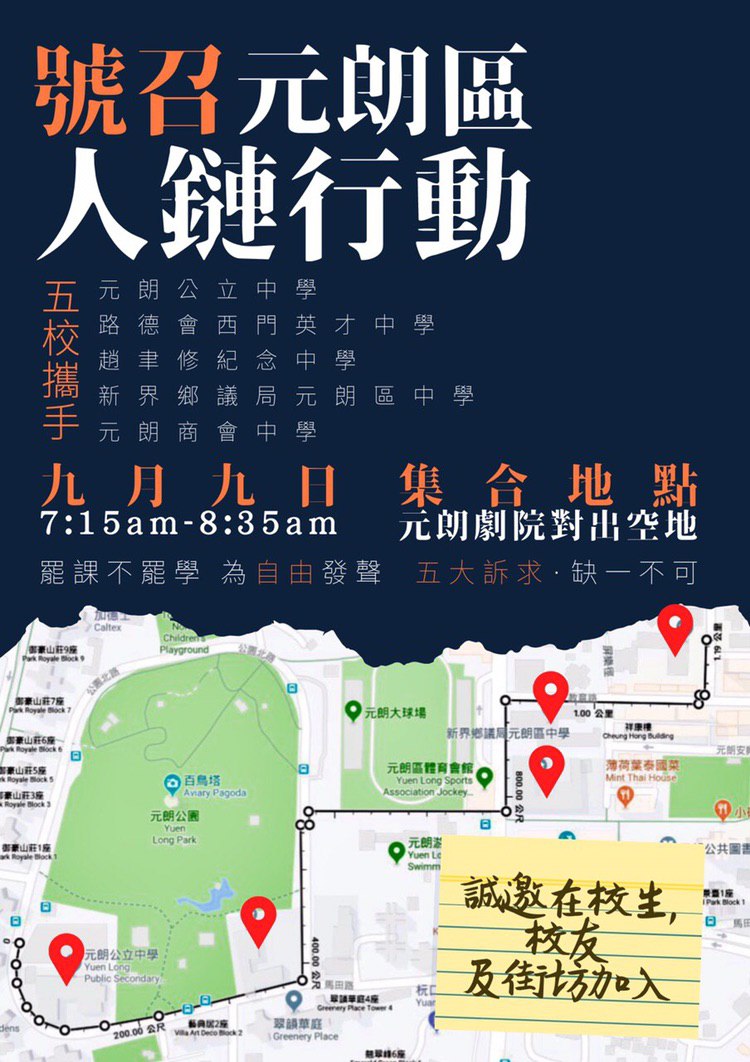

A general strike took place on August 5th, with seven different assemblies rallying across the city. Police stations were surrounded by demonstrators every night, and protests began regularly escalating into dangerous clashes with gangsters. Two days in a row, on August 12 and 13, Hong Kong’s only airport was shut down after a young medic lost her eye to a police bean bag. August was punctuated by three more days of mass action: a peaceful demonstration on August 18th, with 1.7 million people in the streets, and the formation on August 23rd of a two hundred thousand person human chain stretching from the city to the mountains, modeled after protests in the Baltic Countries precipitating the fall of the Soviet Union. Clashes culminated on August 31, only to be overshadowed that night by a horrifying incident of police violence on a halted train in Prince Edward Station. Three protesters have since disappeared and are widely believed to have been killed by police.

2 – FIGHT FOR FREEDOM, STAND WITH HONG KONG

Hong Kong has been an international free market haven since its occupation by the British in 1842. Under the Qing dynasty in the 18th century, most of China’s foreign trade was limited to a small port system in the upper Pearl River Delta. This arrangement, known as the Canton System, confined foreign merchants to the riverbanks outside city walls and forbade them access to the interior. Trade was subject to a litany of regulations, and much of Britain’s imperial motivations for Hong Kong lay in bypassing these laws so that the Empire could gain easy access to goods such as tea, silk, and porcelain. To balance their resulting trade deficit, Britain began importing massive quantities of opium from India into Chinese markets, and after two Opium Wars, Hong Kong was formally ceded to the British. By 1864 it was the leading center for finance on the South China Sea.

Over the years people flocked to Hong Kong not only in pursuit of economic opportunity, but also to escape the floods, famines, and wars that characterized the collapse of the Qing Dynasty. Under British occupation, merchants were no longer subject to the same confinement under the Canton system and could conduct trade without the interference of Chinese law. The already vibrant commercial hub was then given yet another influx of capital when many of the wealthiest capitalists fled the revolution on the mainland, settling in the city. These factors contributed to making Hong Kong a strange oasis, home to a blend of merchants, financiers, and proletarian families, but also to refugees, criminals, and rebels fleeing persecution by Chinese authorities.

Hong Kong remained a model port city up through the 20th century, becoming an indispensable trade hub for Mainland exports as China began opening its industries to international markets in the late 1970’s. Given its history as a hyper-capitalist grayzone, Hong Kong is unsurprisingly one of the world’s most unequal cities in terms of wealth. It also has one of the world’s most overvalued real estate markets, leaving those at the bottom—and young people in particular—with few options for social mobility, and a sense of foreboding about the future.

After the 1997 British handover of Hong Kong to China, these problems have been compacted by a slew of legislation which aims to gradually incorporate Hong Kong under mainland rule before the official 2047 deadline, when the “One Country, Two Systems” policy will legally expire. It is this foreclosure of the future that has animated Hong Kong’s summer of discontent.

August 31st. Somehow everyone knew that today will be big. Maybe it was the triad attacks early in the morning, or the arrests of movement celebrities the day before. In any case, the government revoked the permit for the march at the last minute. To circumvent this, a church took up organizing the march, since the government can’t legally ban religious gatherings. All the MTR stations near the meeting point are shut down, so we take a ferry from Kowloon to Hong Kong Island—this was before they started raiding the ferries. We exchange knowing glances with another group of conspicuous youth at the other end of the boat. We arrive late, a little after 2 PM. It’s raining, and the crowd had already started to march. Tens of thousands of umbrellas deftly maneuver over, under, and around each other beneath the gunmetal skies. Along the route we encounter riot cops guarding police stations, but the march i just getting started, and now is not the time. The procession really did feel religious: silent and somber, everyone wearing black, occasionally breaking out into lamentful hymn whenever we passed by police, with the words “sing hallelujah” chanted in multiple languages until they all ran together into a single, ominous melody.

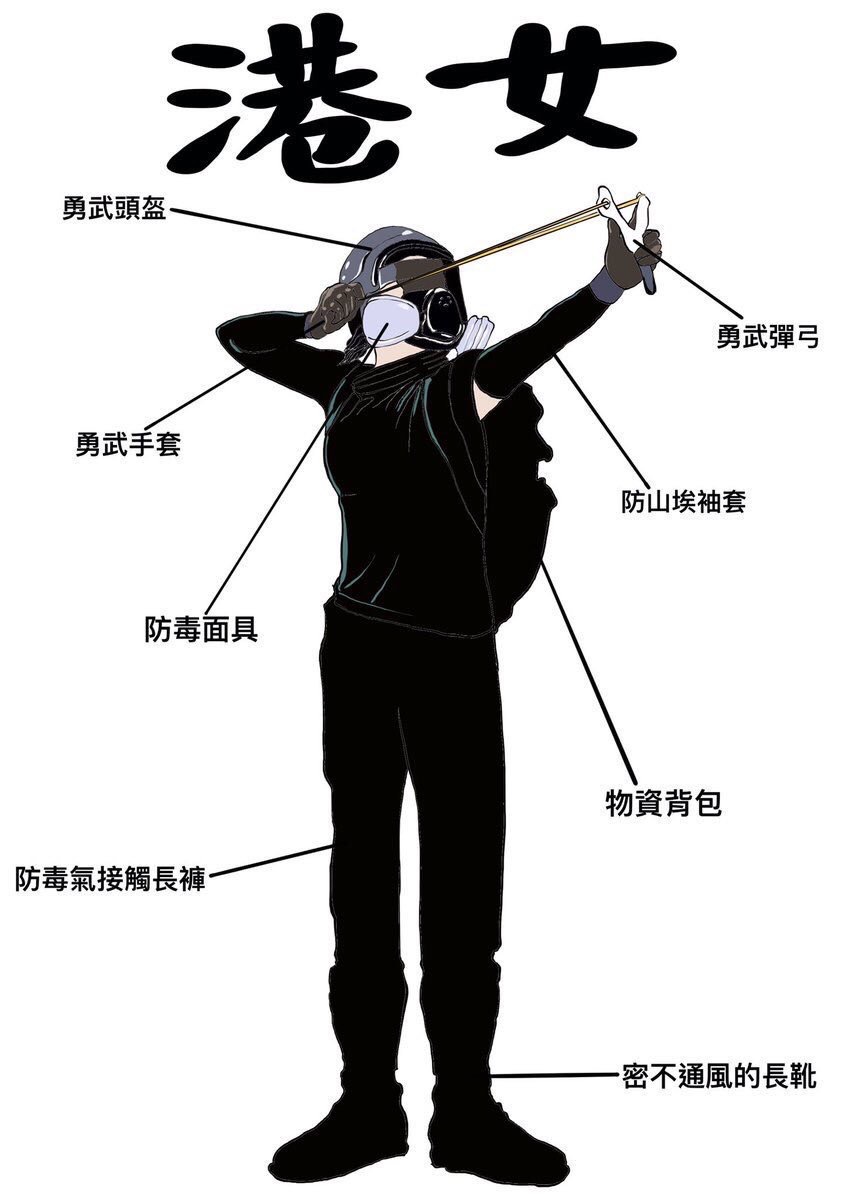

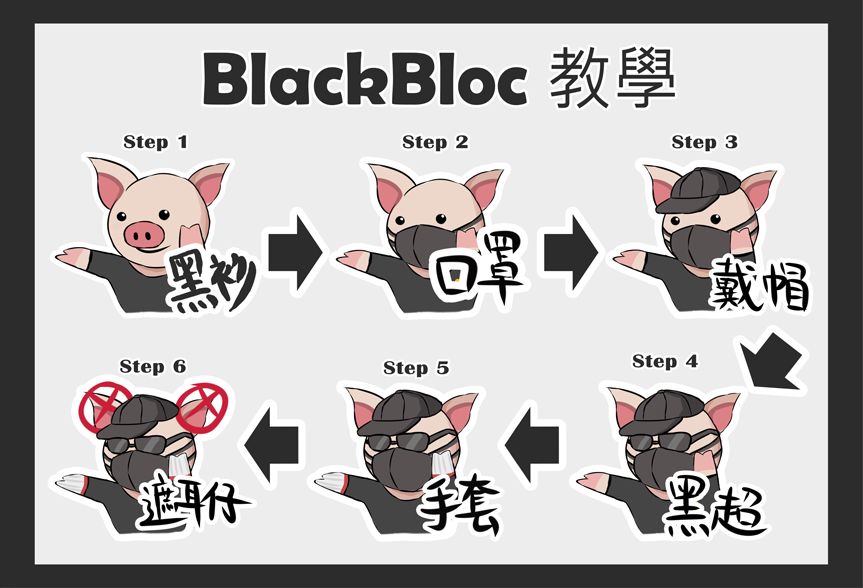

When the march officially ends we check Telegram to find the next meetup point and make our way to a large shopping district. We sit on the curb with our friends, watching an endless stream of protesters spill through the street in front of us. People gear up slowly, adjusting each other’s helmets and gas masks. The crowd swells over the course of an hour, we watch as thousands of people transform from a religious congregation into the largest black bloc we’ve ever seen. The mood is tense with anticipation.

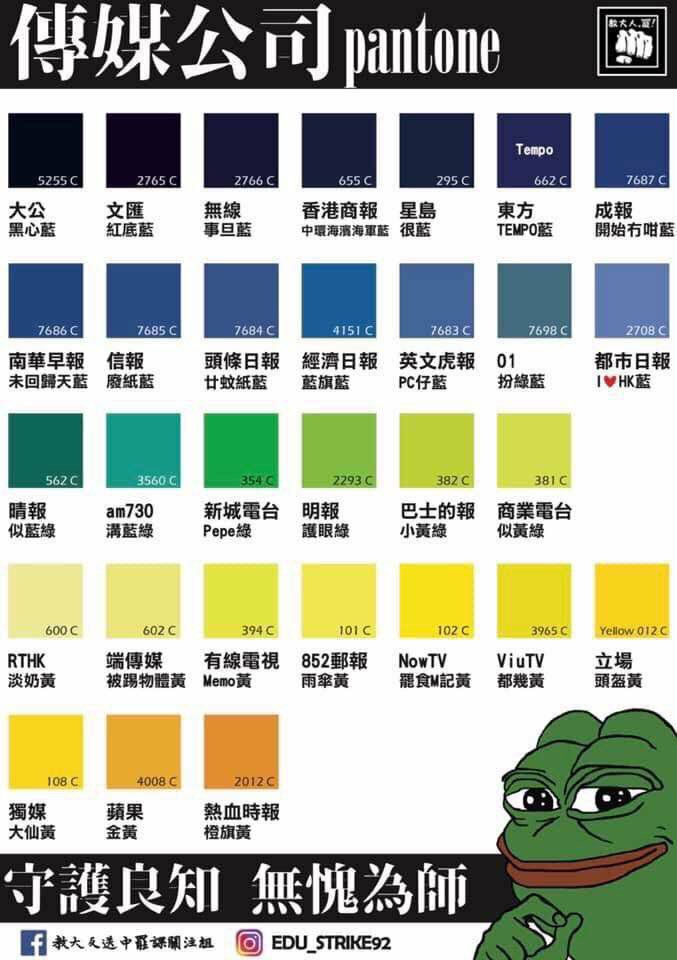

The “democracy” the movement advocates is best understood as an umbrella term for civil liberties including freedom of speech and freedom of the press, as well as other reforms won during the 1967 anti-British riots. The fear of having these freedoms revoked motivates a large portion of youth, many of whom have spent their entire lives watching the Communist Party’s authoritarian grasp slowly envelope their home. The movement’s ecstatic, creative power could be considered the production of the participants’ non-identity with the Communist Party’s omnipotent model of governance, a dazzling display of what people can do in defiance of mass surveillance and state terrorism.

It is no accident that the most intense clashes with police are not taking place on Hong Kong Island—the Manhattan of Hong Kong—but across the water in the proletarian districts of Kowloon. Mong Kok, site of the Fishball Riots in 2016, “the intersection of triad activities, prostitution, cheap eats, and hawkers,”[i] resembles a nightly war zone as flash mobs play cat-and-mouse with frantic police squadrons for weeks on end. Local teenagers in balaclavas and Yeezys build barricades shoulder to shoulder with Pakistani migrant workers as police fire tear gas indiscriminately, poisoning the thousands of residents living in cramped high-rises above. It would be naive to assume that there are no people in the movement who have set their sights on creating a new ethno-nationalist identity, but the fact that the movement’s partisans have made defending these neighborhoods a central strategy demonstrates that the “Hong Kong Way” could offer belonging to all who participate in the movement.

Tear gas canisters scattered on Nathan Road, Mong Kok. [Sam Tsang, SCMP]

Teenagers and migrants are not the only ones fighting for Hong Kong: the movement is thawing many formerly unbridgeable social divides. In response to Chinese state propaganda pitting the undisciplined youth against the more “rational” adults, brigades of elders formed in mid-July to show their sympathy for the struggle. These formations of the “Silver Haired”—some in their 70s and 80s— don yellow vests and stand in front of charging riot police, attempting to delay their advance and buying time for the young frontline protesters to escape. A #MeToo rally on August 28th brought over a hundred thousand women into the streets to protest widespread reports of sexual harassment and assault at the hands of the police. There was even a demonstration honoring wildlife and pets who have suffered from prolonged exposure to tear gas.

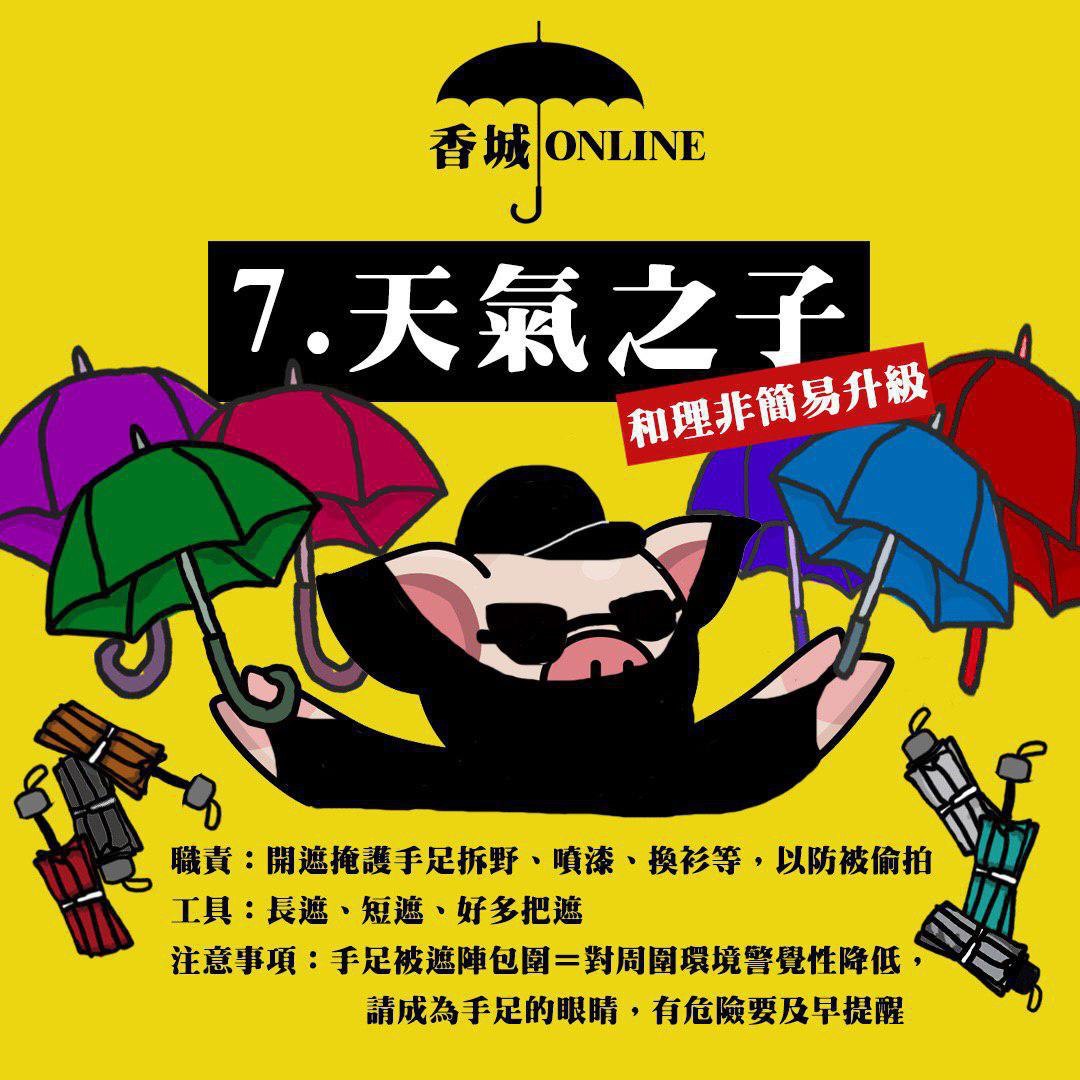

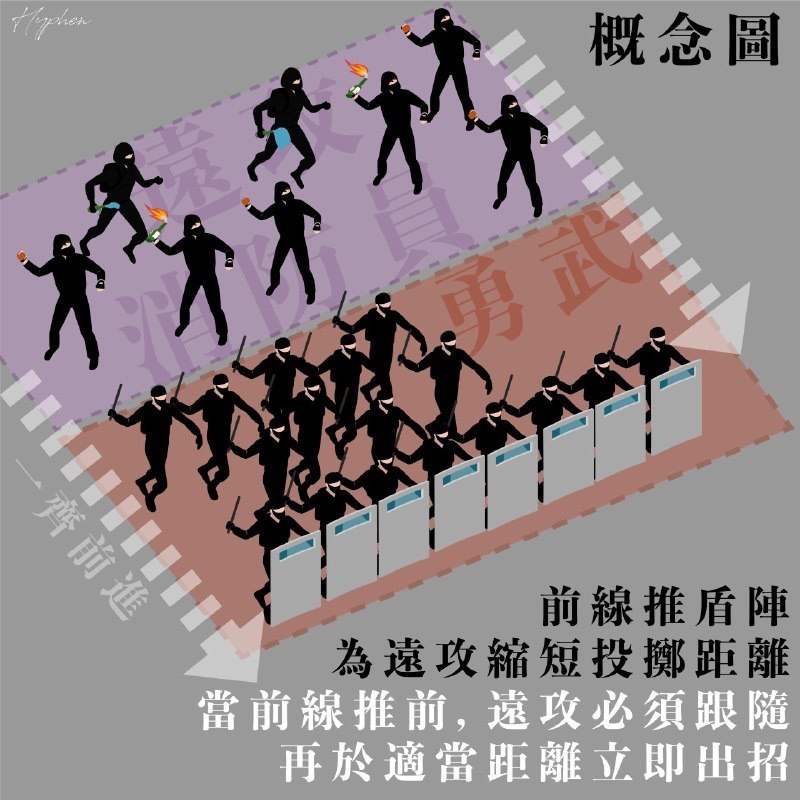

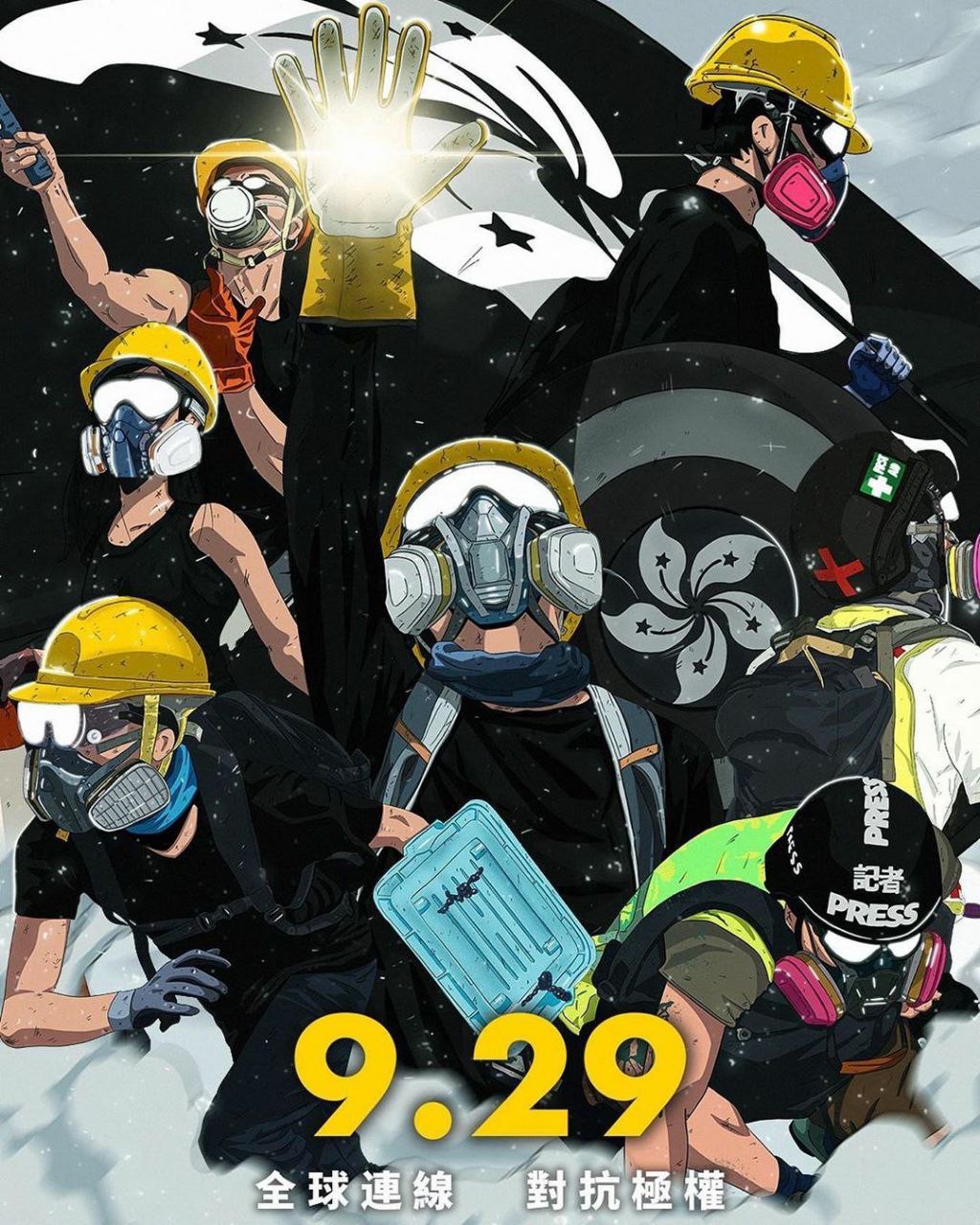

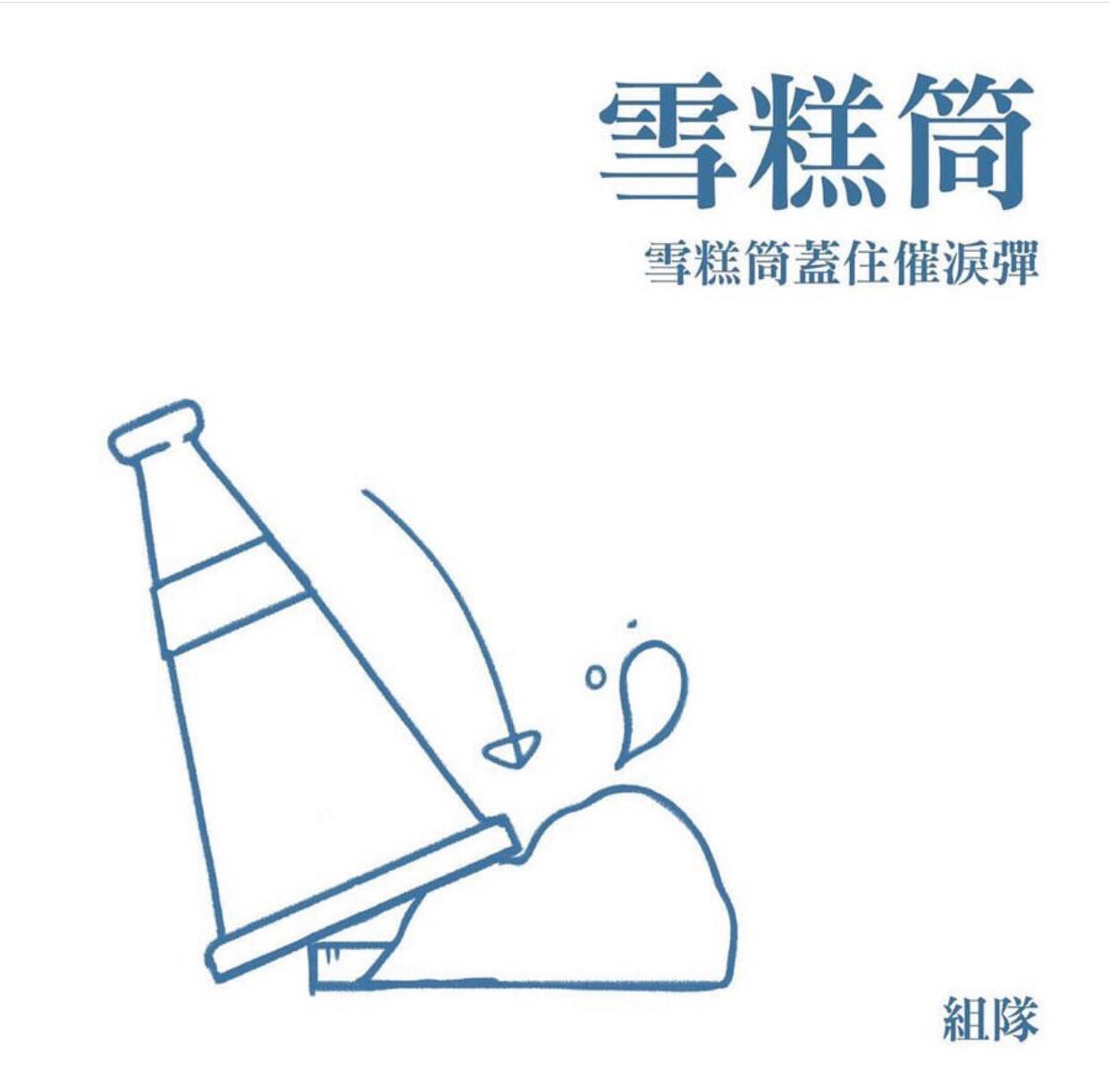

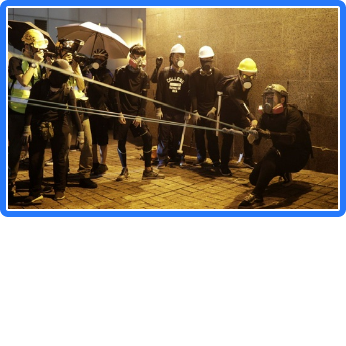

The march makes its way from the shopping district towards the Chinese military’s Hong Kong headquarters. The mood switches from ominous to electrified. Everyone is in full gear. A friend runs to catch a tag on a giant bridge and a dozen strangers with umbrellas swarm around them, shielding them from surveillance. As we near the headquarters, a few protesters climb up a building and start tearing down a billboard advertising the Chinese government’s upcoming 70th anniversary. The crowd cheers as the symbols of domination are torn down and tossed to the streets below. We arrive in front of the barracks via a highway overpass, with even more protesters filling the streets below us. We know viscerally what is about to happen, and everyone is ready. Below, the police have set up water barricades and are readying their weapons. A few cops look out from the rooftops high above. The cops raise the orange flag, indicating that they’re about to start shooting. Volley after volley of tear gas canisters bounce across the bridge, each one calmly neutralized by one of several teams armed simply with traffic cones and water. Frontliners to the left of the building advance slowly in staggered formation behind a shield wall of repurposed traffic signs, and the police start shooting at them. To the right of the building, other frontliners take advantage of the distraction and rush in, throwing rocks at the police and molotovs at the building itself. Behind us, logistics teams are lining the guard rail with supplies of freshly refilled water bottles and broken bricks. We find ourselves in rows and rows of faces crouched behind masks, umbrellas and yellow helmets.

August 31 2019 from Bureau Spectacular on Vimeo.

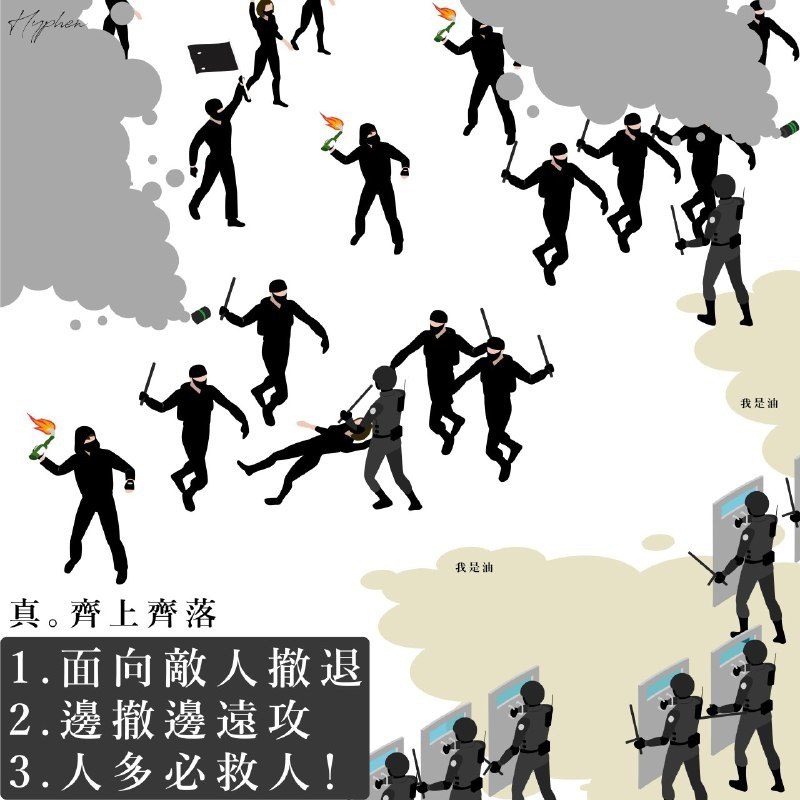

The movement’s insistence on having “no divisions, no denunciations, and no betrayals” was formulated on July 1st, when people stormed the Legislative Council. That day, a debate ensued between some who were in favor of occupying the building, as was done in Taiwan’s Sunflower Movement, and those who argued that there was no need to fill its vacant halls waiting for arrest. Moments before the Raptors—elite units of riot police—arrived, some protesters ran back into the LegCo to physically carry away those who remained, saving them from the inevitable beatings and arrests. From this point on, “we come together, we leave together” became a core value.

The movement is united behind five seemingly impossible demands, standing firm against relentless police repression. The government’s refusal to negotiate has preserved the practical unity of the movement and staved off any moment where splits could emerge. This unity is both a blessing and a curse. On the one hand it has created strong bonds between frontline fighters and peaceful protesters, referred to respectively as the movement’s “hands and feet.” On the other, the movement risks adopting a romantic view of unity that obscures the very real divisions nascent within the movement offering different conceptions of what it could mean to truly “Liberate Hong Kong.”

A recent graphic protesting the deportation of migrant domestic worker, Yuli. The Chinese characters on the sign read: “Immigration Department and the Police are Equally Corrupt” and the text on the bottom: “Domestic workers are comrades too”

3 – TECHNOLOGY AND MAGIC

We can look to how the movement is organized to determine its ethical consistency, and look to its targets to get a sense of its strategic intelligence and limitations.

CARCERAL SOCIALISM

The worst nightmare of many Hong Kongers is the apartheid system in China’s Xinjiang region, where the native Muslim population is subject to constant surveillance. Government checkpoints are set up throughout the region to hold people in place through face scans and assessments of the on-line activities of Uighurs and other Muslim groups. These checkpoints are supported by a biodata collection program that forced the population of the region to submit DNA, fingerprints, blood samples, voice signatures and iris scans and, in some cases, face prints at local police stations. Government-mandated GPS units are installed on cars and people are required to carry smart phones so that their movement can be tracked. Surveillance systems are used to monitor children’s behavior in school where they are told they must identify as “Chinese before anything else.” Devout Muslims are disappeared into “re-education camps” where they are told that if they renounce their past religious practice, learn Chinese and embrace state ideology they have a better chance of being released.

The militarized surveillance and mass incarceration system being implemented in Xinjiang has been developed jointly with major Western companies, justified in the language of a “War on Terror.” This includes the participation of players such as Erik Prince, brother of US Secretary of Education Betsy Davos and founder of the notorious private army, Blackwater. Prince’s company has since been wrapped into the Frontier Services Group, based in Hong Kong and funded by the mainland CITIC conglomerate, a major state-owned enterprise. Rather than simply rebranding Blackwater’s mercenary market, Frontier Services instead emphasizes total logistics and supply chain management, and recently signed a large contract for a training base in Xinjiang. The group thereby represents the Chinese joint-venture expansion of the global military-surveillance complex, working to funnel Chinese capital into natural resources in Africa via private equity investments, and securing the interests of Chinese capital across Asia via the establishment of militarized logistics bases in Xinjiang and Yunnan.

In this context, local Chinese companies have been able to build on the global expansion of surveillance and incarceration to develop a series of advances in facial recognition, population tracking and, of course, internet censorship. These technologies are now the basis for major export contracts, as Chinese firms train foreign companies in poor countries dealing with the strain of rapid growth to implement similar technologies—in Uganda, where the state is moving to curtail in the internet, in Zimbabwe, where Chinese surveillance technology is being incorporated into new urban development, and in Pakistan, where the Chinese military has a number of bilateral training and coordination agreements. Among the protestors, the involvement of Hong Kong capitalists in the same projects remains unmentioned, but the fear of having the most extreme of these surveillance systems applied to the city became more and more salient as arrest numbers began to climb.

Unable to see or hear much, let alone communicate verbally amidst the tear gas, we primarily synchronize our actions. This chaos is not determined by disorder, but by its speed; symbiosis and mindfulness create order. Suddenly, a water cannon emerges from the road behind the military headquarters and begins spraying straight into the air. A momentary confusion takes over the crowd—nobody expected that the water would be laced with ultraviolet blue dye. We get word that a band of riot cops is advancing from behind us, and despite totally outnumbering the police, we decide to move on. We escape down a side street. Feeling secure in numbers, we parade at a leisurely pace, removing our gear for a second: everyone is exhausted. We walk past someone who hands us sausage egg mcmuffins from McDonalds. By the time we regroup outside the police headquarters, kids have built an enormous barricade with an entire construction site’s worth of looted materials. After about an hour of baiting the police with sporadic projectiles, the cops charge and the barricade magically becomes a wall of fire. The march disperses, and thousands of zoomers in motorcycle armor are running in every direction. It’s already 10 pm, but the night is far from over.

THE SHAPE OF REVOLT TO COME

We will now identify a few of the essential tools used by the protesters to outmaneuver these advanced forms of control.

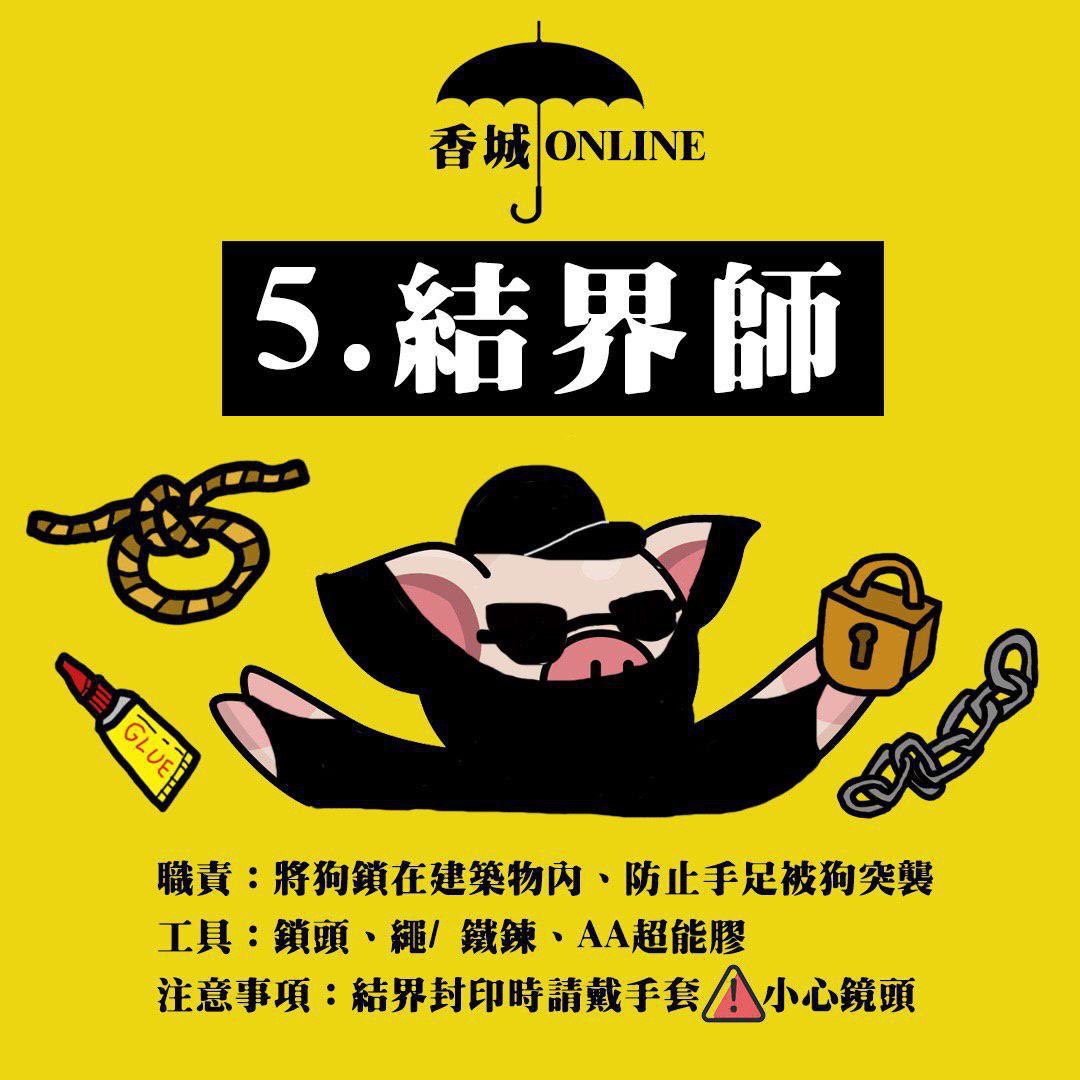

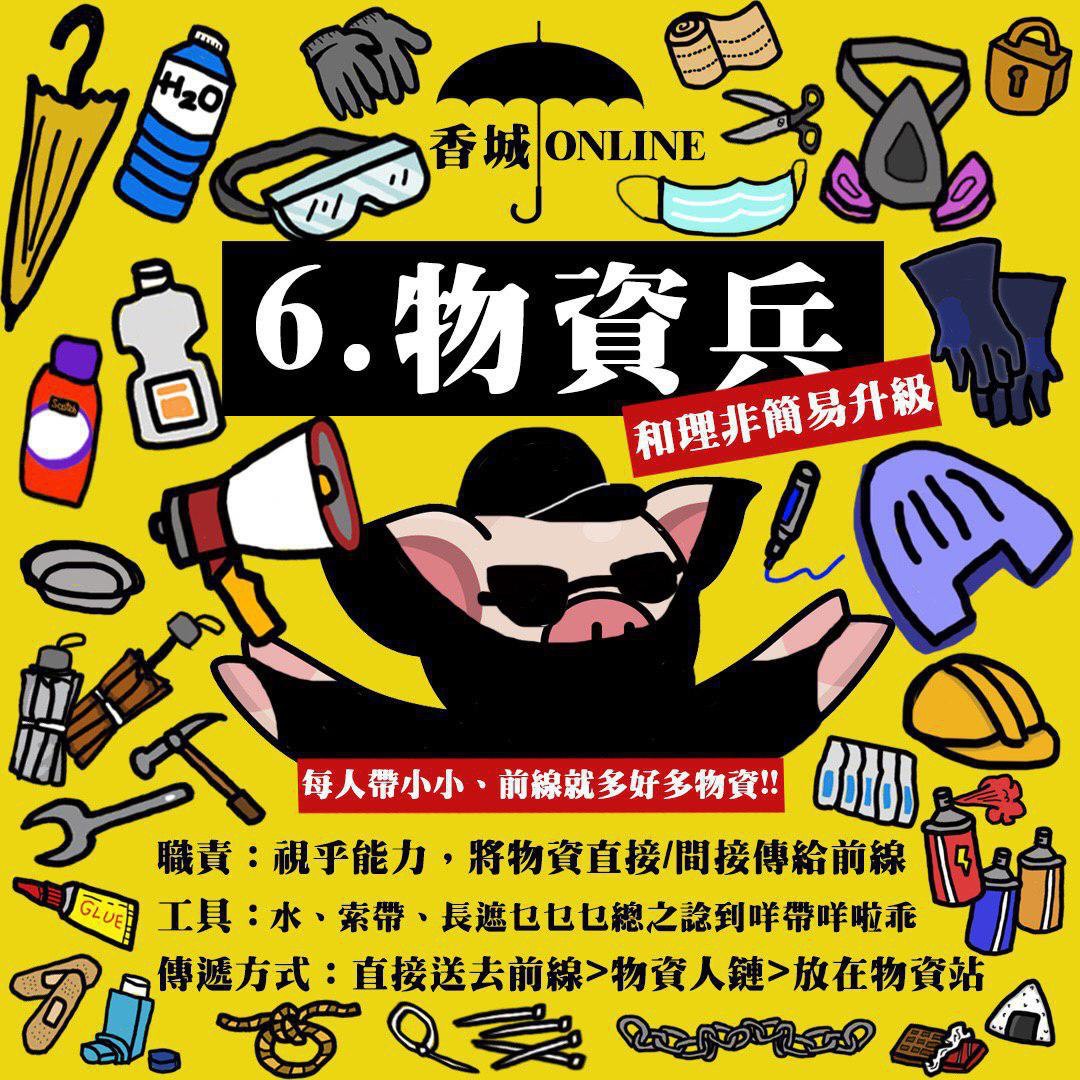

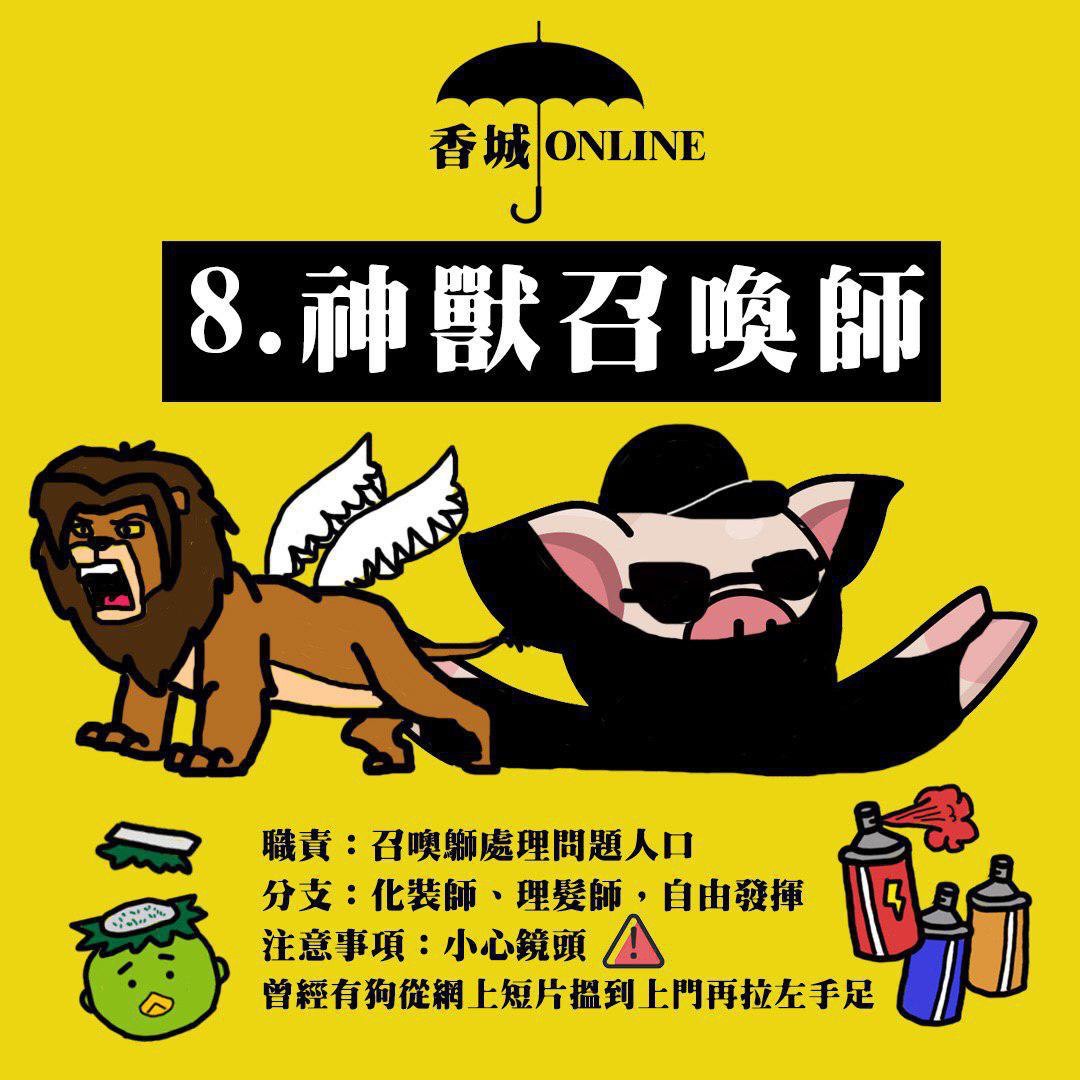

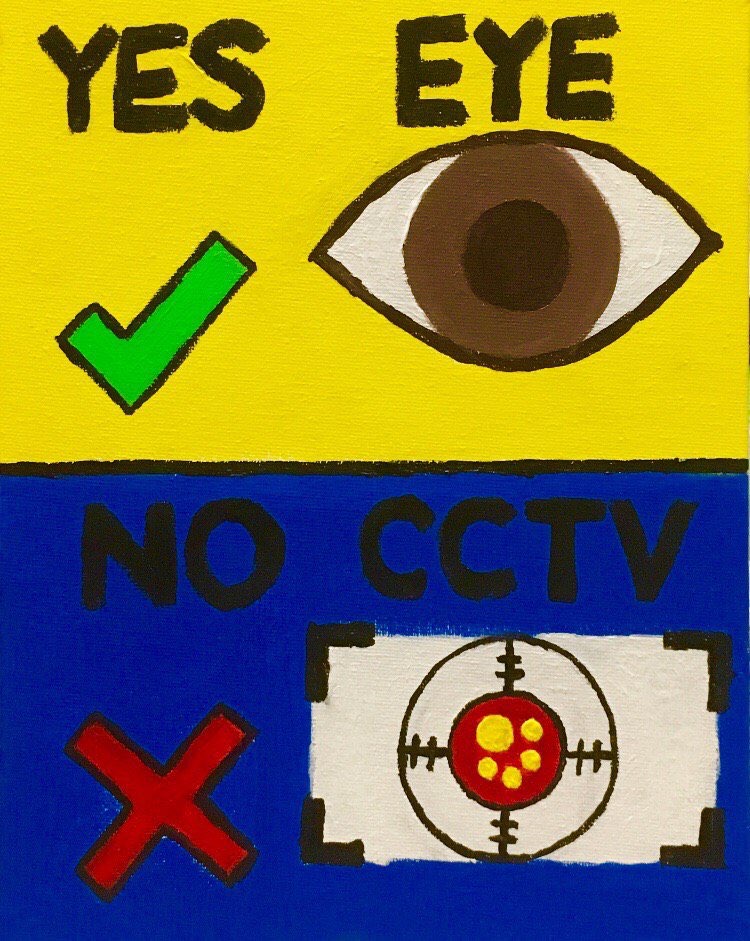

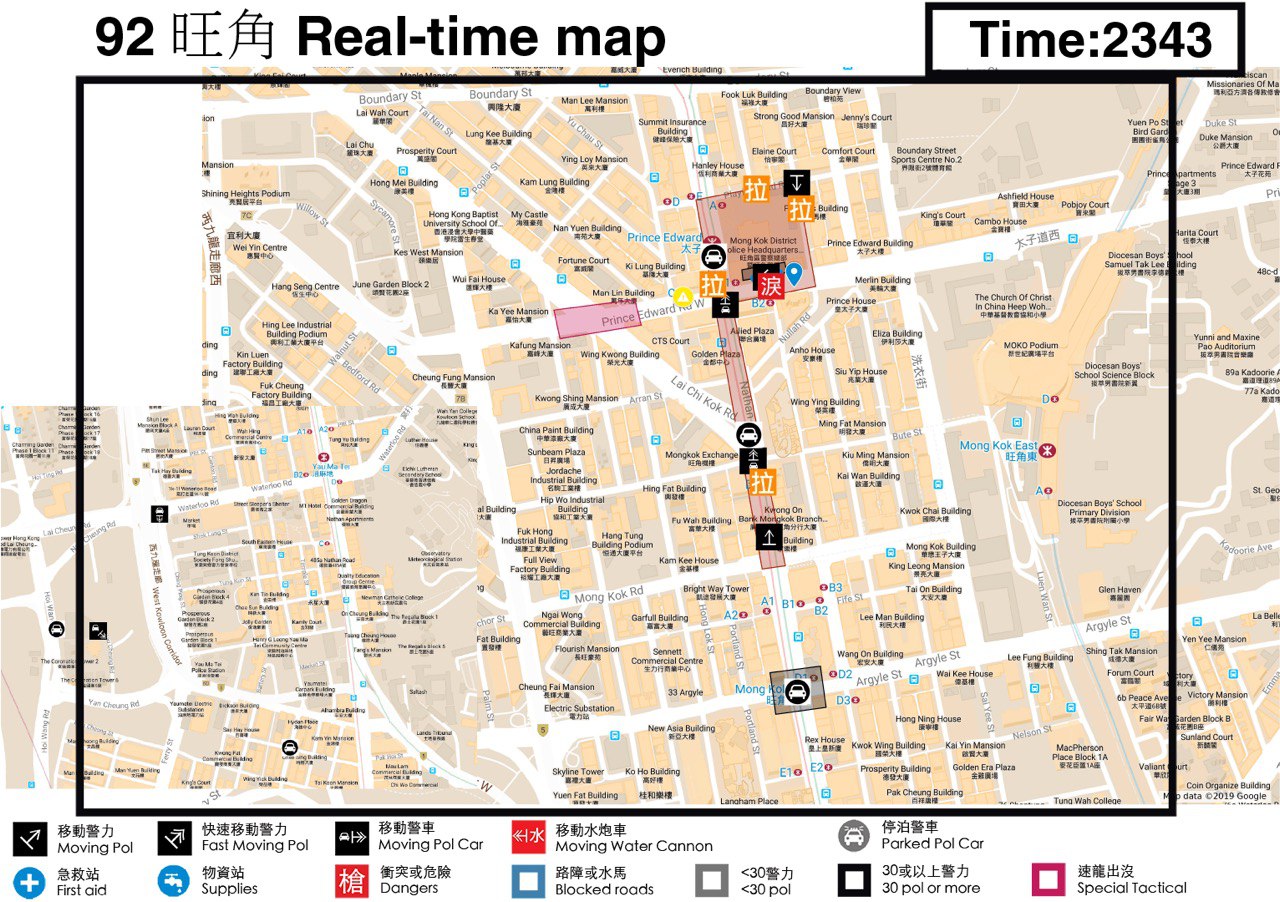

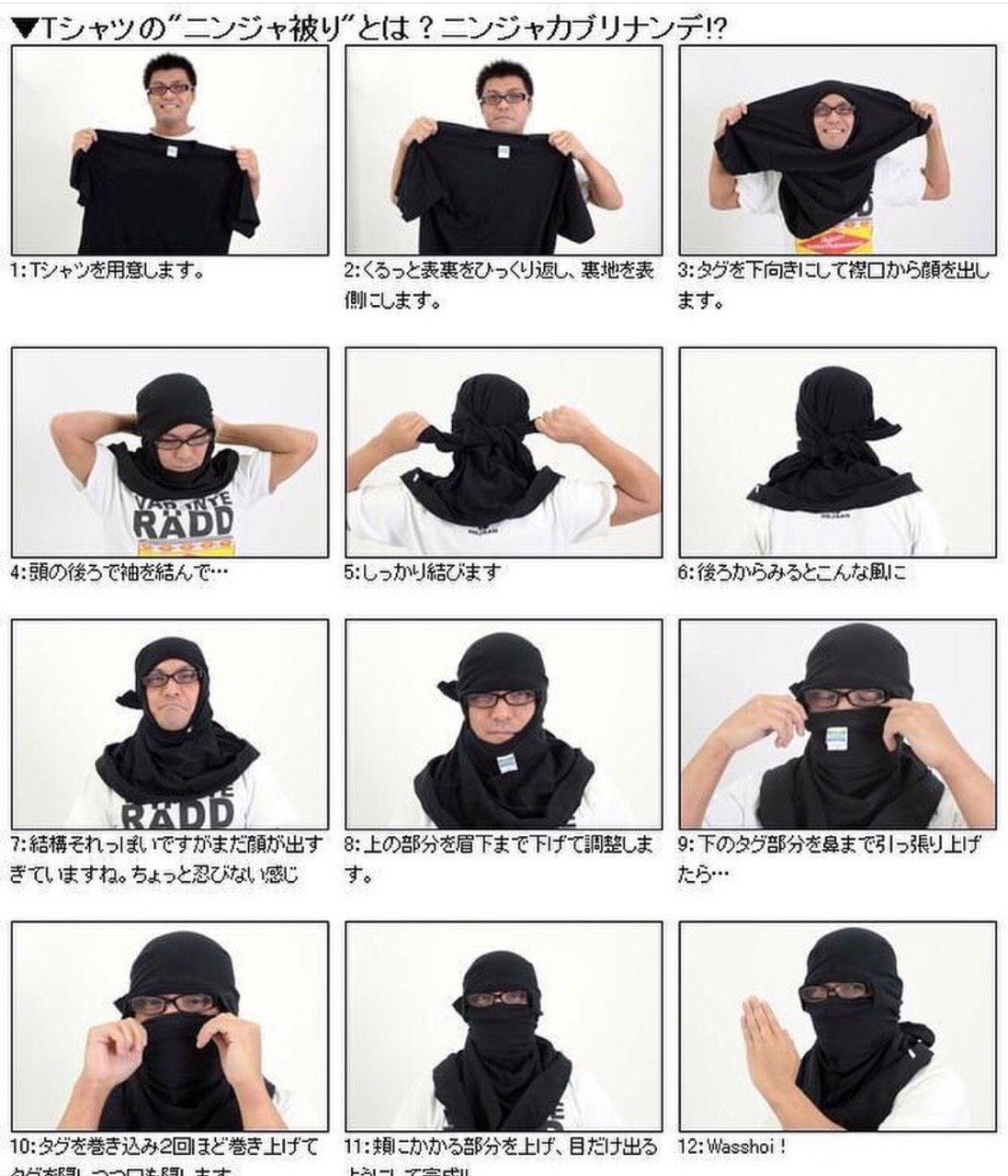

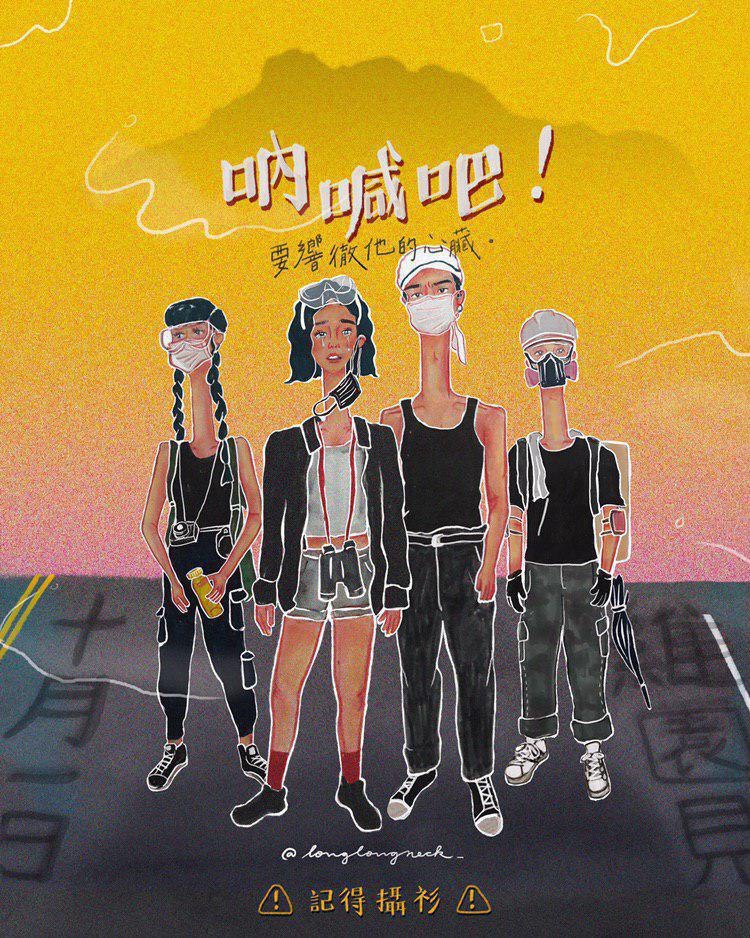

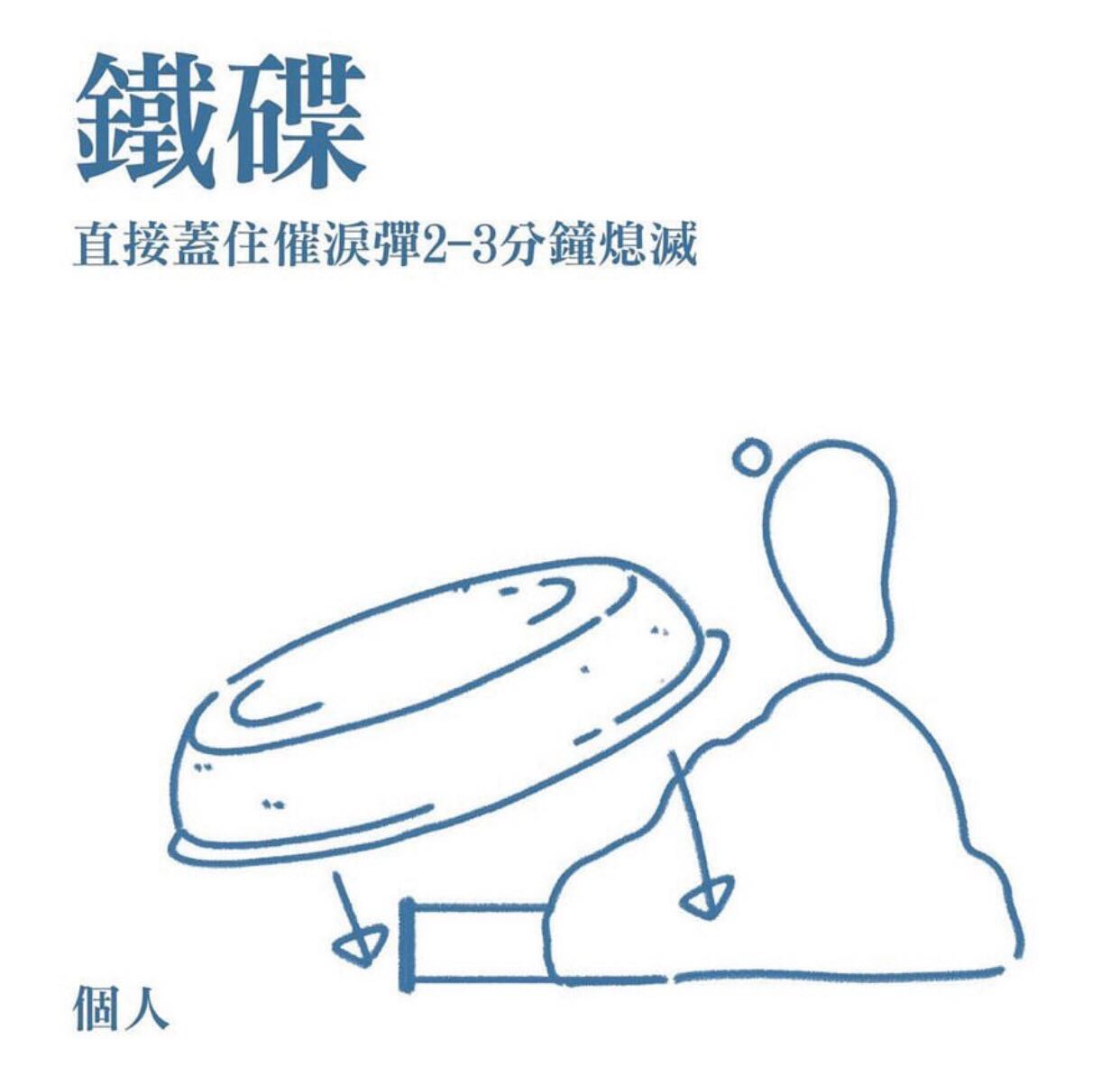

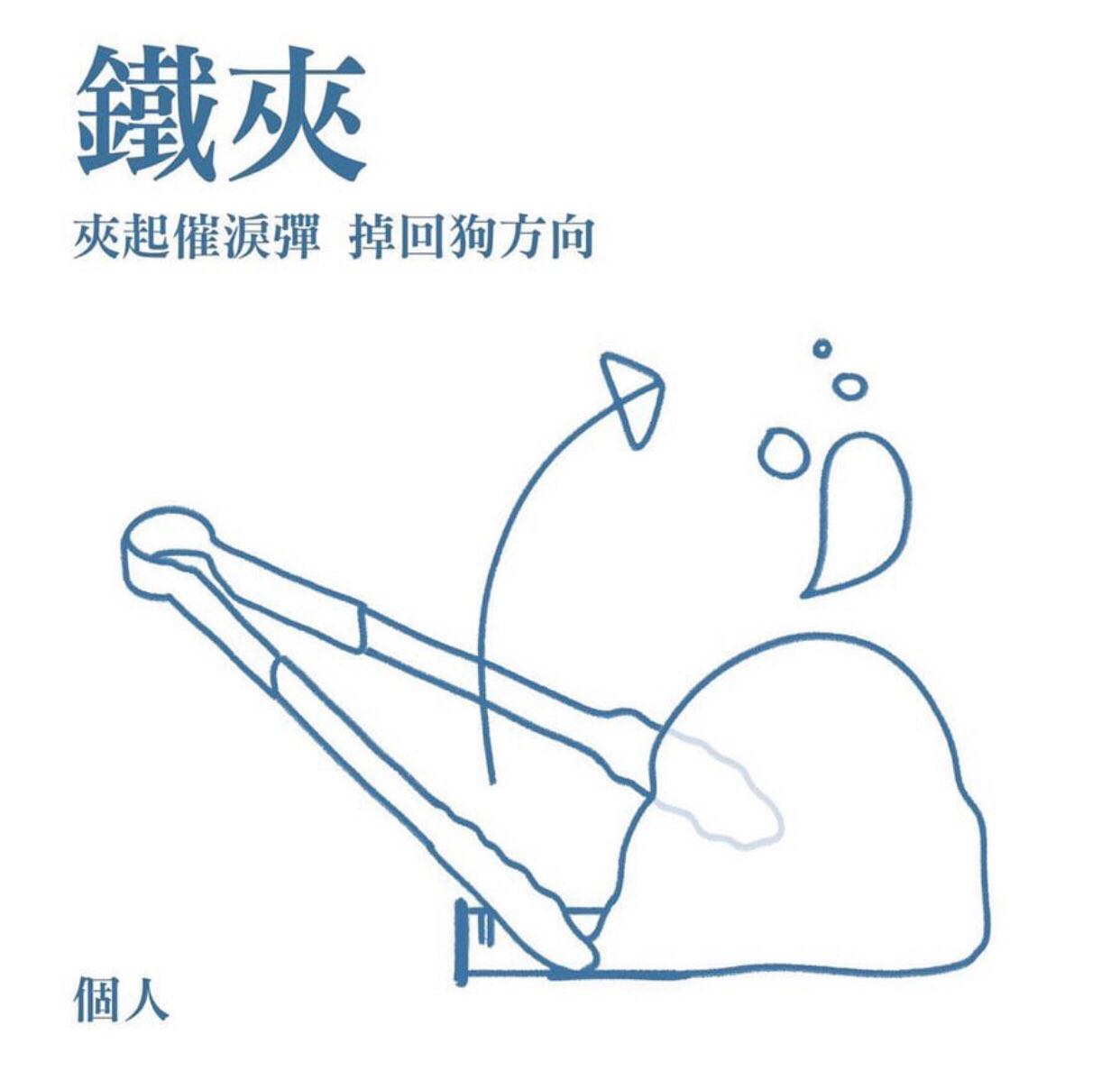

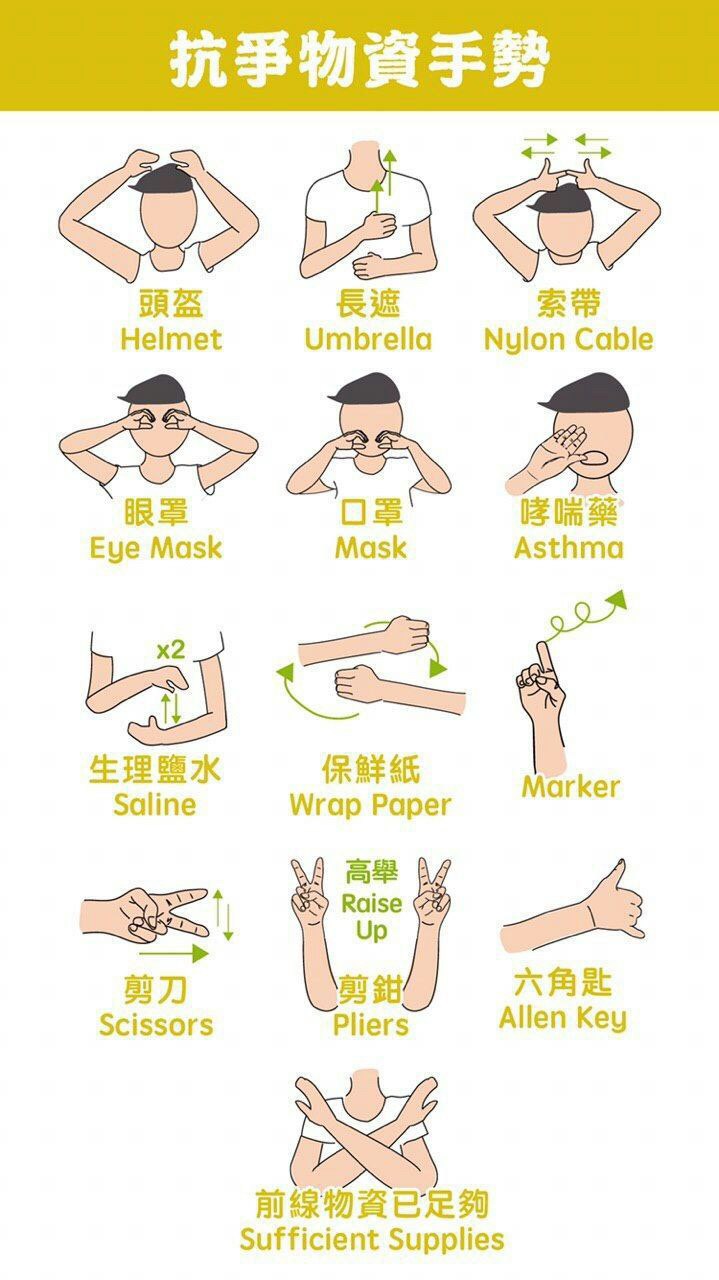

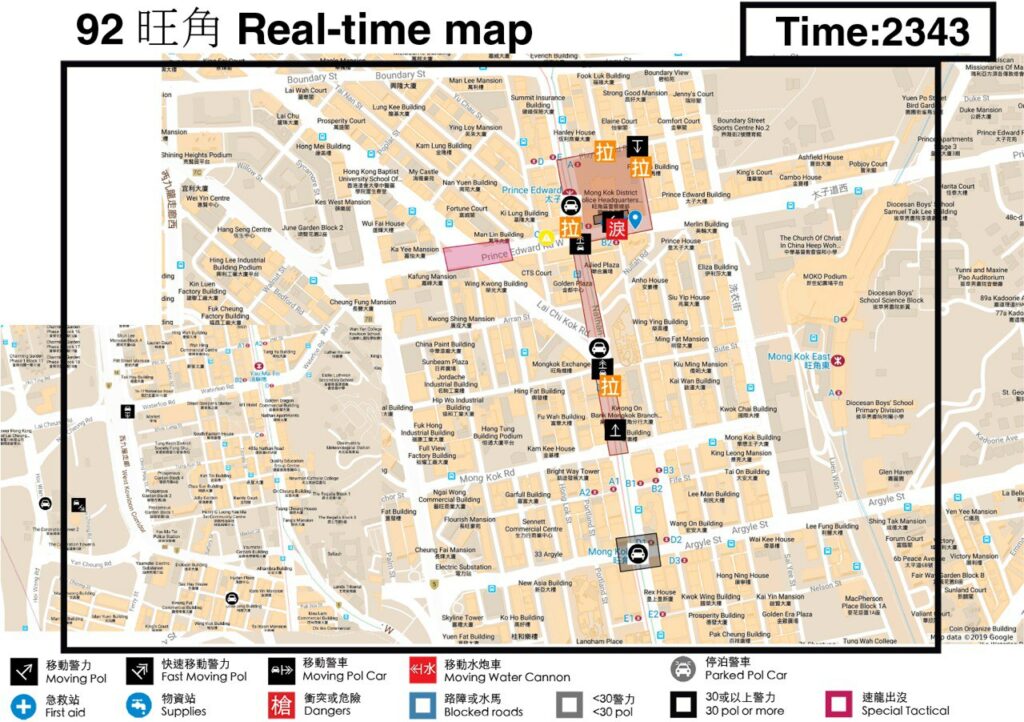

The frontlines are organized anonymously. People pay cash for SIM cards to register temporary phone numbers on encrypted messaging apps like Telegram, where individuals sign up for tasks like building barricades or disabling traffic lights. In contrast to black blocs in America, where affinity groups are based around trusted friendship networks, nobody on the frontlines in Hong Kong knows each other outside the protests. This ensures a degree of security: if someone is caught, they will be unable to inform against other protesters, who they only ever meet behind masks and screen names. Labor is specialized, and tasks are voluntarily coordinated via Telegram groups containing thousands of people. Some groups organize to bear colored flags, so that people in the back of the demonstration can know what’s happening on the frontlines, while other groups are “smoke extinguishers,” tasked with using steamed fish plates and water jugs to contain and neutralize tear gas. Those who can’t risk being in the frontlines run communications networks from home, synthesizing information from people on the ground and disseminating it to tens of thousands of people via live mapping websites. Online forums such as LIHKG provide a platform for long-format discussion and voting on the strategic direction of the movement.

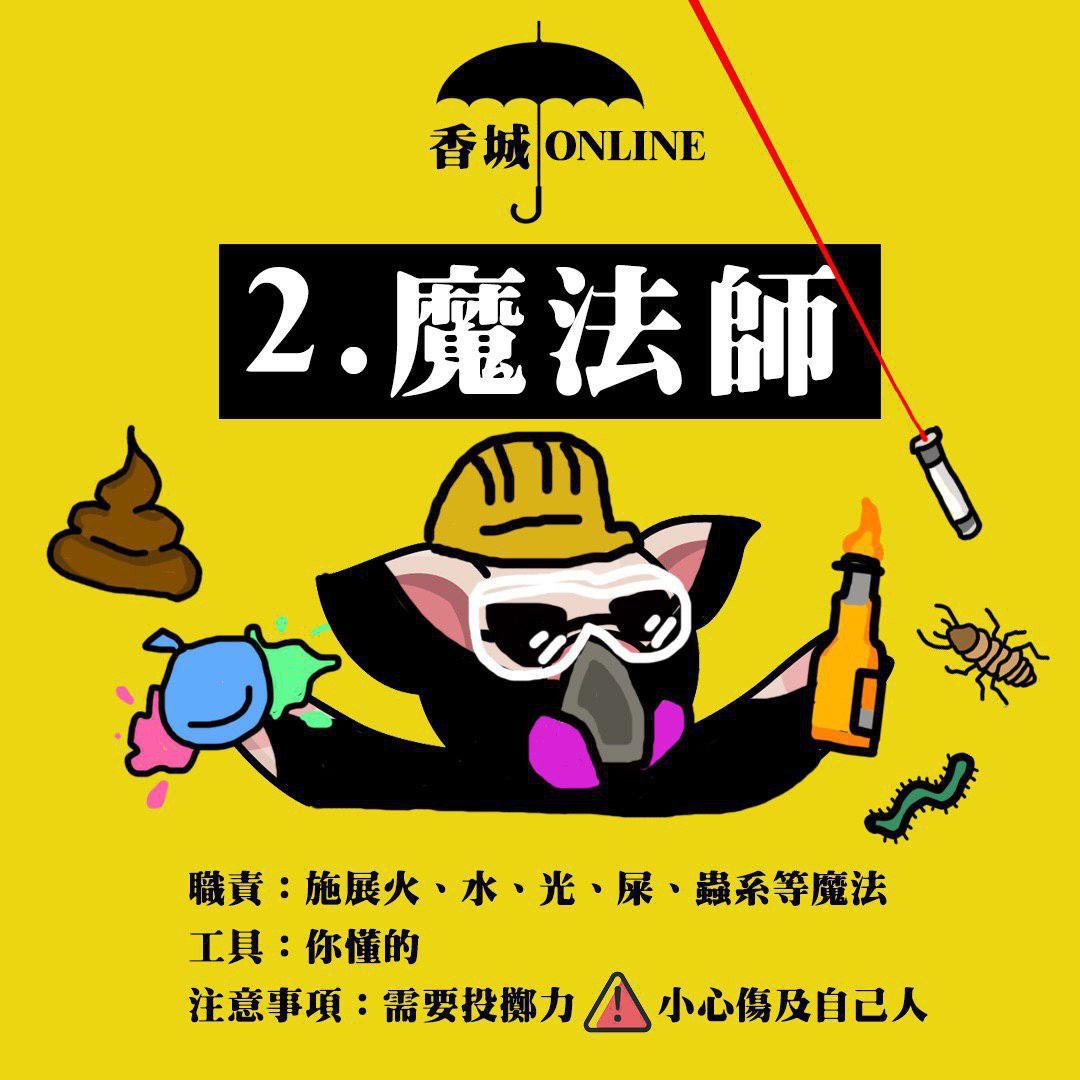

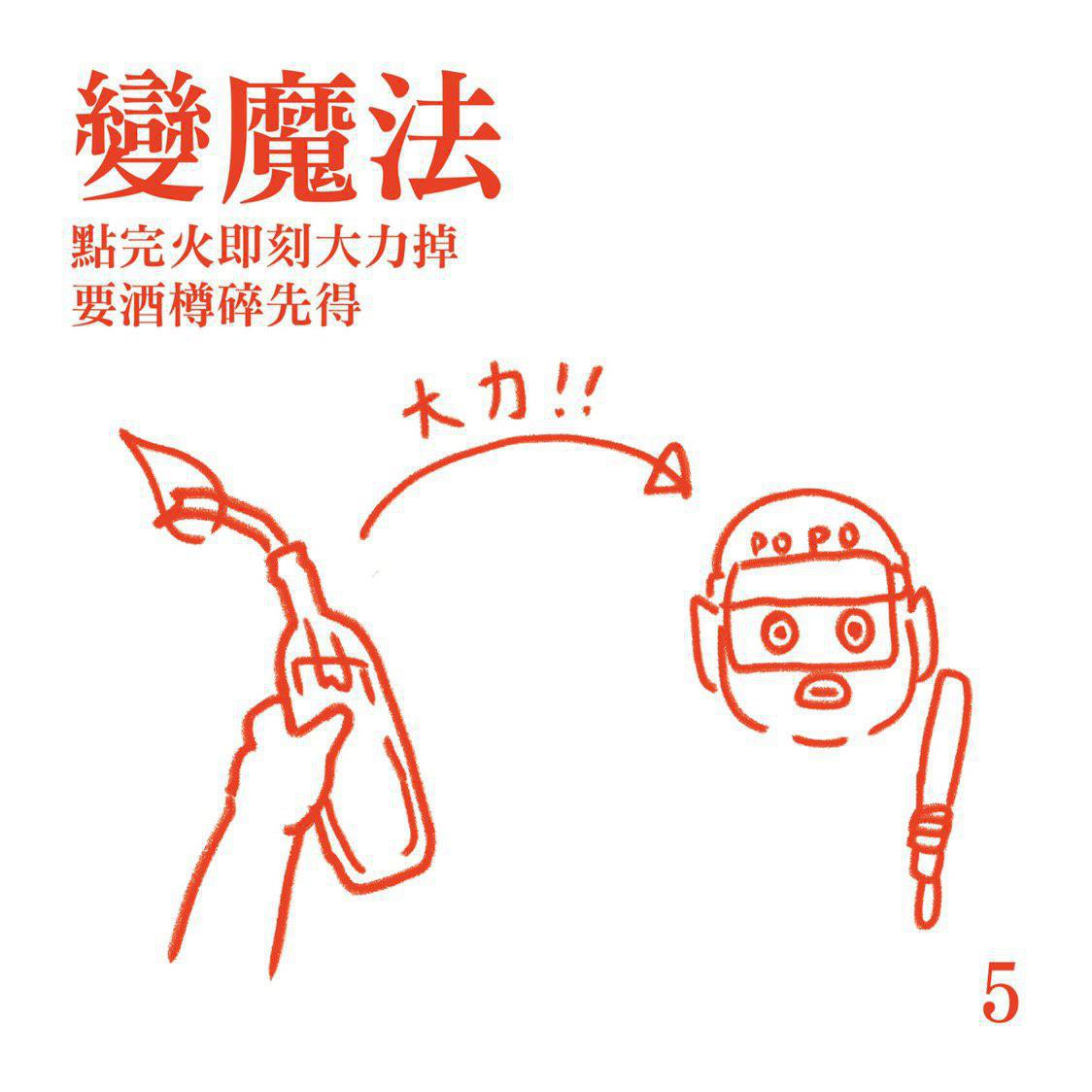

When the frontline protesters use “fire magic” (slang for throwing molotovs or burning barricades), “light mages” use laser pointers to keep the cops from advancing, giving crucial distance for the protest to breathe. Shined directly at the lens, a blue laser will permanently disable police cameras. On nights after big demonstrations, people flood online message boards with stories about how they “dreamed” of using “magic” while “shopping.” Metaphor and euphemism allow participants to discuss tactics openly while retaining a degree of opacity. Umbrellas and sunglasses, disposable rain ponchos, cheap surgical masks, traffic cones, a surplus of mass produced electronic goods: these are simply the objects at hand, the basic components of life in Hong Kong. Like the ubiquitous yellow safety vests in rural France, protesters have turned their everyday surroundings into an arsenal.

During a demonstration on August 24th, protesters used a portable angle grinder to fell a surveillance tower. In a form of proletarian research, they dismantled the tower, and quickly examined the parts inside. After confirming that the towers were constructed using the same components as the surveillance systems in Xinjiang, more than twenty towers were attacked that day. That evening, we asked an older comrade what he thought about the action: “This was the smartest thing people could have done. The government said they were not going to be used for facial recognition. The only way to verify that is to tear the thing down.” The next day, the company that supplied the parts for the towers announced it was canceling its contract to install an additional 350 of the same “smart lamp posts” throughout the city.

An hour later, a flash mob pops up in a major shopping district of Kowloon and quickly begins barricading the narrow streets. We get word of the action and make our way as fast as we can. The police have the same idea. As we walk, we are overtaken by a caravan of approximately fifty riot vans making their way through traffic on the two-lane road. By the time the ‘dogs’ (slang for police) arrive, the flash mob has dispersed, headed elsewhere to do exactly the same thing. The dogs exit their vans, in full riot gear and armed to the teeth, but there are no “protesters” to be seen. The composition of the crowd has changed dramatically, and the cops are fucked. There are fewer youth in masks, and residents from the area are pouring out into the streets to see what’s happening. They heckle the cops: “What are you even doing here? There’s no demonstration!” The cops awkwardly dismantle the barricades at a turtle pace, hindered by the angry mob of residents. After about an hour, the police climb back in their vans and leave. We split as well, taking the long route home to avoid the trains and catch some more tags. By the time we arrive in Mong Kok, an almost identical situation has played out. The police are again surrounded by thousands of angry citizens, cursing at them in colorful Cantonese. We see a contingent of Raptors rush out of the police station and into Prince Edward Station—only later did we find out why.

August 31 2019 from Bureau Spectacular on Vimeo.

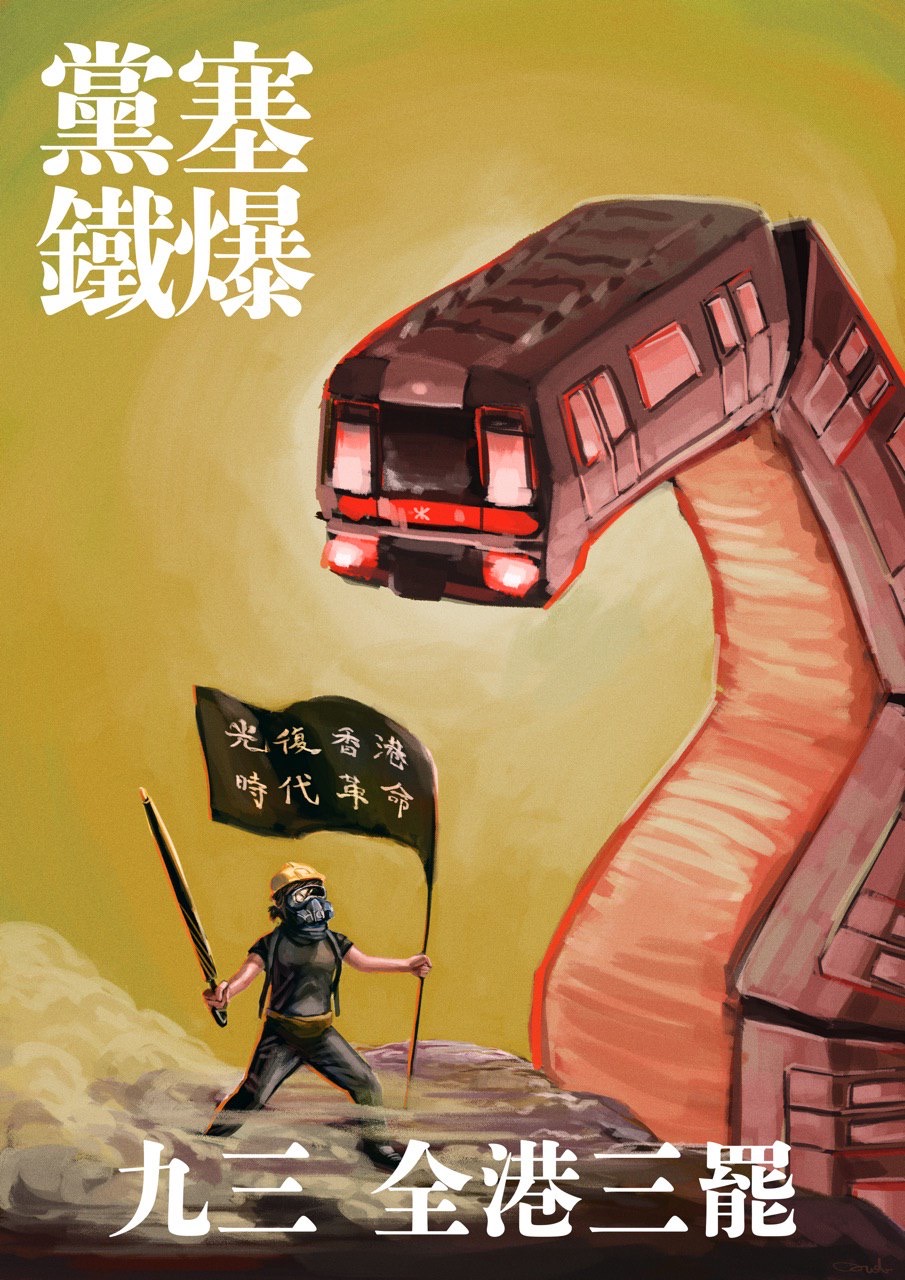

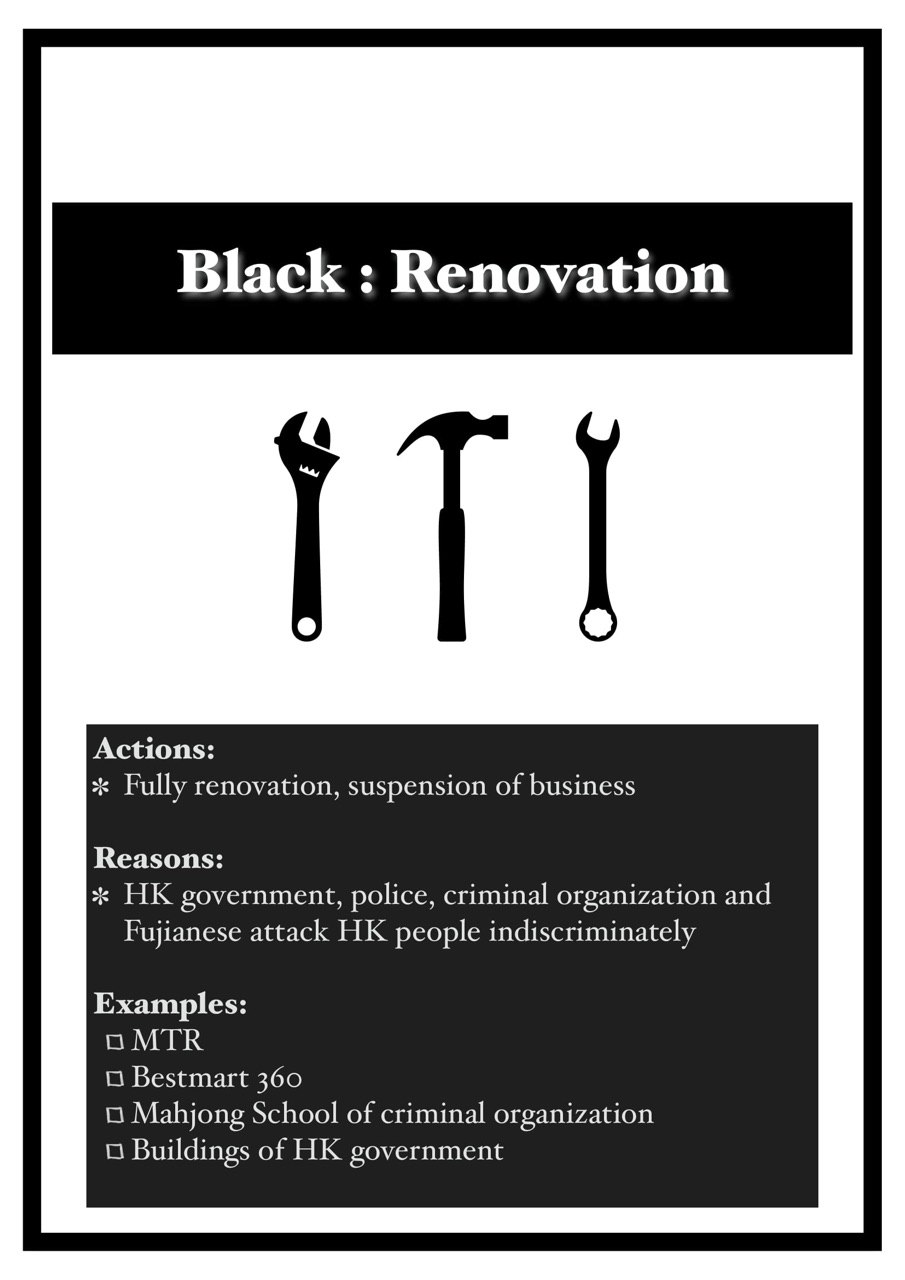

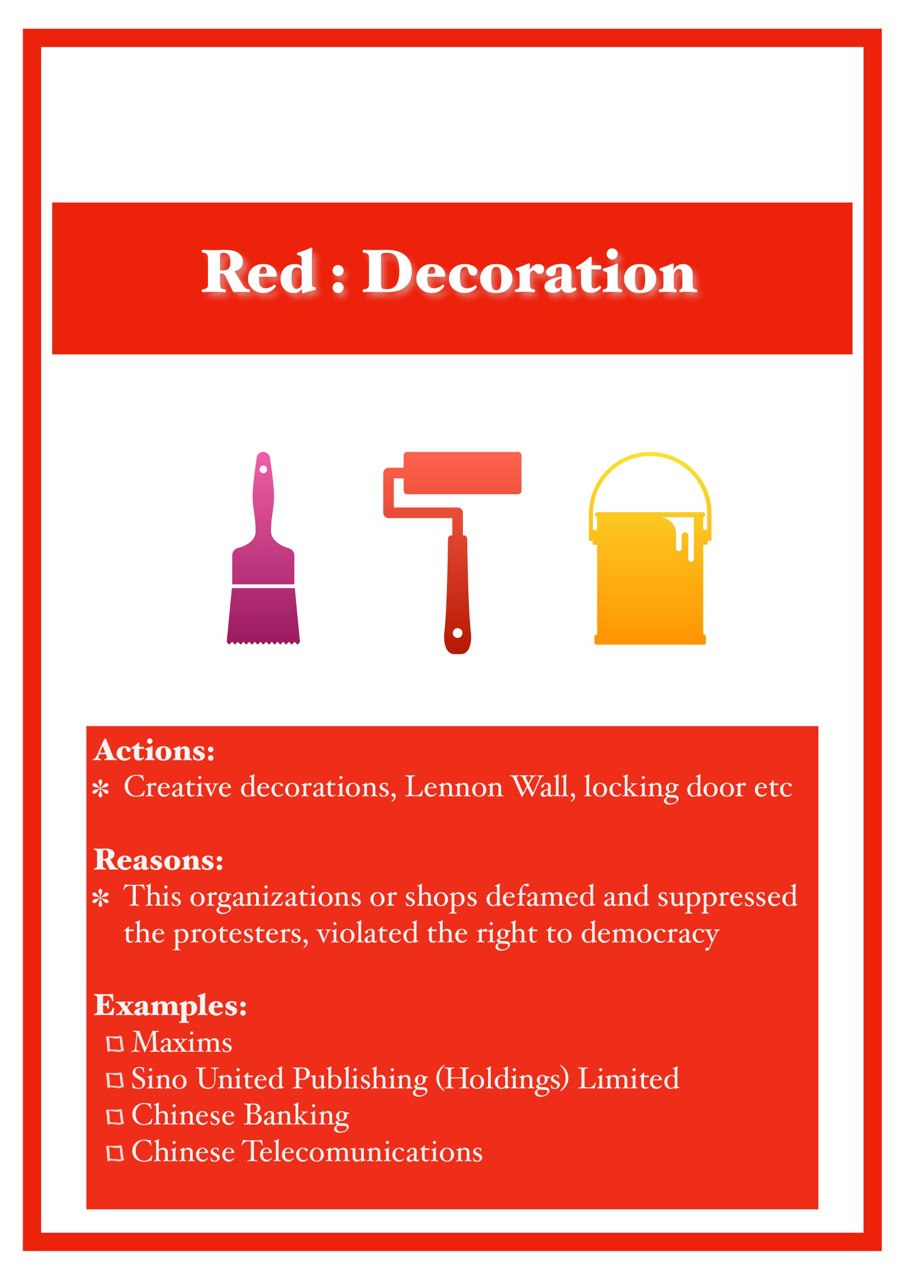

A second example of this type of targeted sabotage is the widespread destruction of the Metro stations. The Metro (Mass Transit Railway, MTR) is vital to the protesters’ “be water” strategy, which requires demonstrators to have access to quick transportation to move spontaneously from one district to another, decentralizing and regrouping. By August 25th, the MTR began cancelling all stops at the stations where the demonstrations were scheduled to happen, forcing people to walk long distances, and stranding people in unsafe areas. A sentiment developed that the state was using public infrastructure against them. Posts online described the MTR as part of CCP’s “national pacifying machine.” Memes and propaganda videos emerged encouraging people to “Join the Fare Dodging Movement.” This is a major shift from the earlier practice of ordered civility, where sympathetic people would leave coins for protesters to buy tickets anonymously.

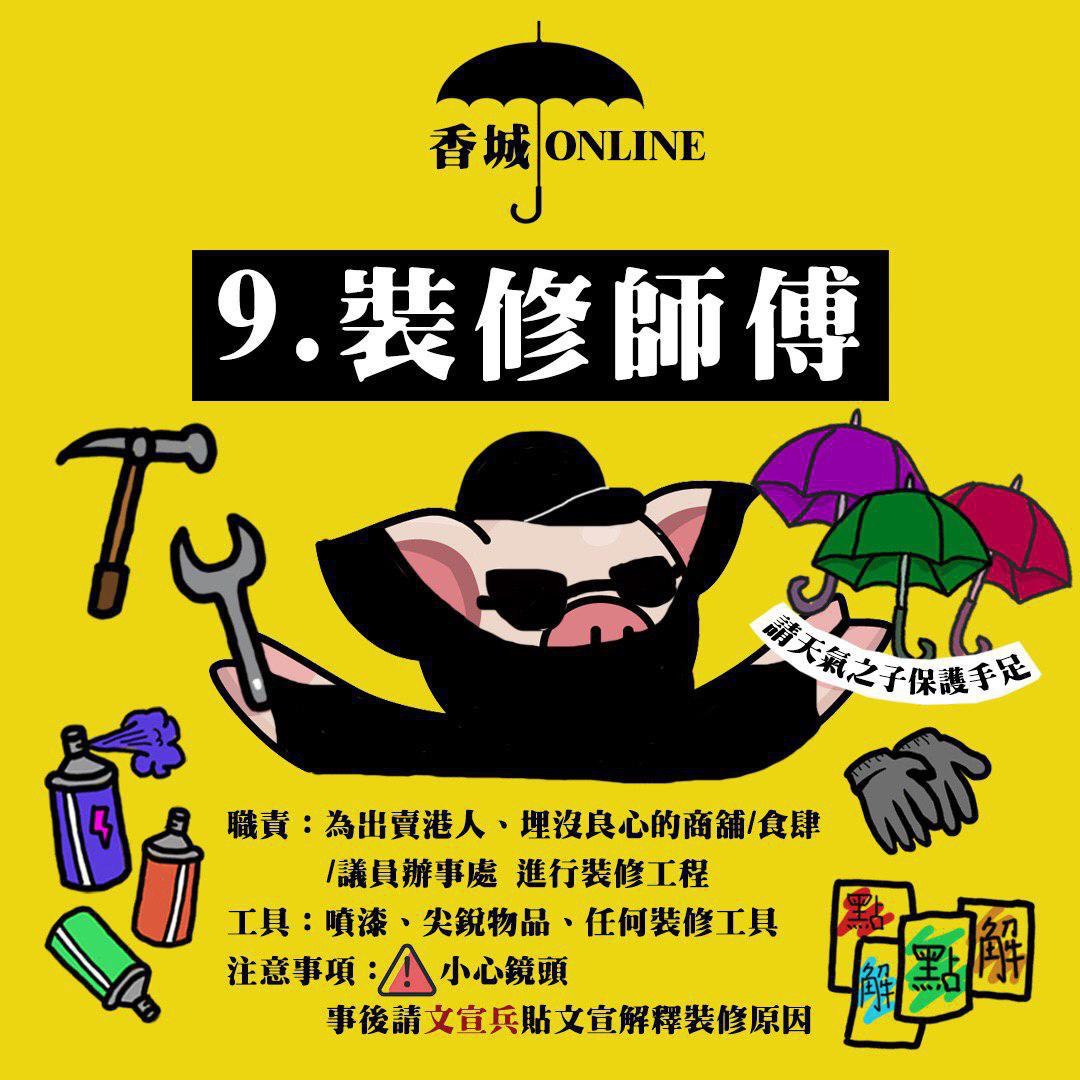

This distrust of the MTR was confirmed on August 31st, when the MTR halted all trains and allowed police to enter the closed Prince Edward station, where they savagely beat both protesters and civilians. The following day, 32 stations, one third of the total in Hong Kong, were vandalized: CCTV cameras and turnstiles were dismantled, stations were flooded with fire hoses, and ticket machines were smashed by teams of “engineers” (movement slang for skilled saboteurs). Soon the police would begin raiding all forms of public transportation, checking IDs and searching backpacks on busses and ferries. In response to the danger of using public transportation, “School Bus” groups emerged on Telegram where thousands coordinated to pick up protesters safely by car.

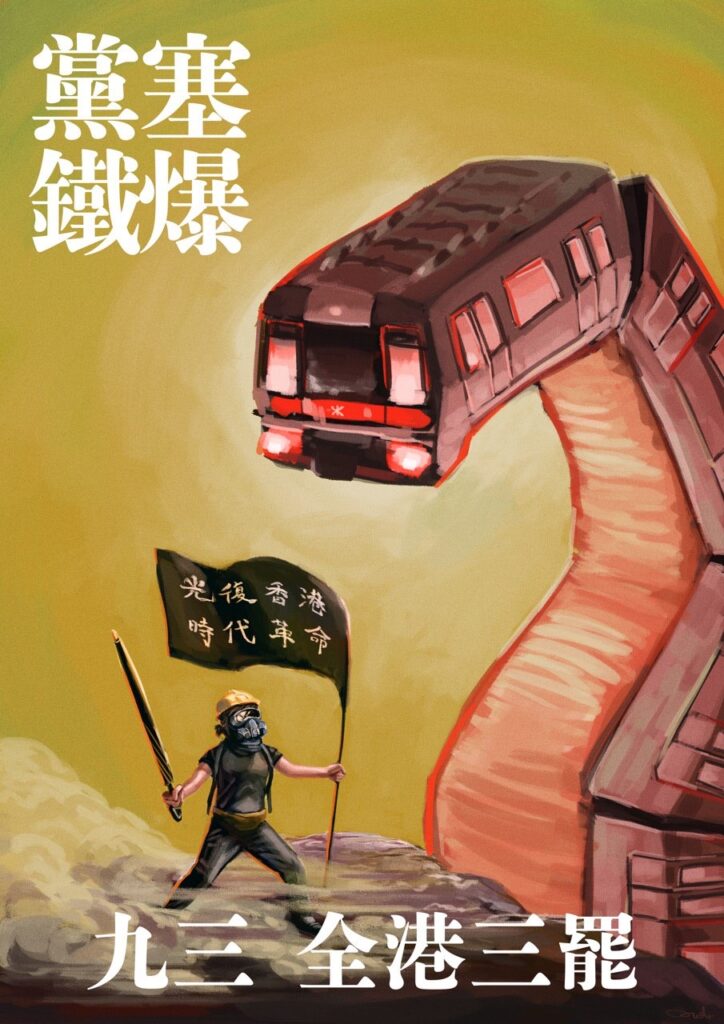

A poster advertising “saam baa” (“three strikes”, advocating the closure of businesses, mass boycotting, and strikes by workers) in protest of the MTR’s collaboration with the police.

4 – BE WATER, MY FRIEND

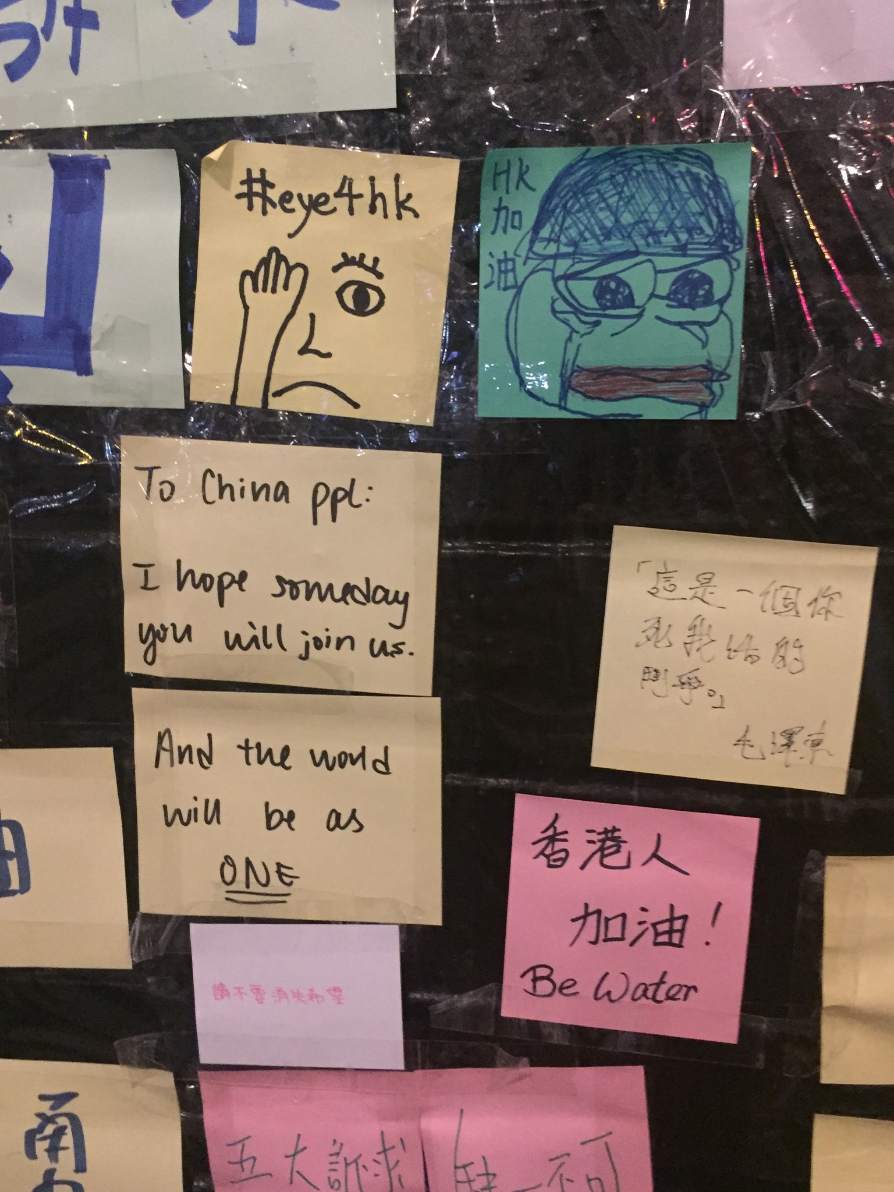

Now that the extradition bill is in the process of being withdrawn, the demands for police accountability have taken center stage. This is now one of the largest movements against police brutality that has ever existed. But this also represents a limit: the movement is stuck in a reactive cycle of provoking the police and responding with indignation at police violence. Revolts stuck in this type of revenge cycle are “fated, over and above the consciousness of the rebels, not so much to vanquish the demonic adversary as to counter it with heroic victims.”[ii] The popular slogan taken from Hunger Games “if we burn, you burn with us” is a perfect demonstration of this policy of mutually assured destruction. Demonstrations are regularly pitched as responses to specific triad or police attacks. The unfortunate consequence of this cycle is that the movement appears stuck in an endgame scenario, waiting to see who can hold out longer, or—tragically—who will shoot first. Only opportunist revolutions can occur within the framework of forming a new government to “restore law and order.” There is no “just” democratic society that Hong Kongers can call upon to save them. To truly end this cycle of violence would mean abolishing the police force itself, and by proxy, capitalism. For a western audience it is worth elaborating the “be water” strategy, which developed in response to the failures of the Umbrella Movement. With its permanent occupations, pacifist discourse, and political leaders, the lessons from this movement created a culture where tactics that do not work are quickly abandoned. The strategy is simple: disrupt and desert. People are still organizing long term in their neighborhoods or coordinating the maintenance and defense of Lennon Walls (message boards spread throughout the city) for example, but the emphasis is on spontaneity, unpredictability, and adaptation.

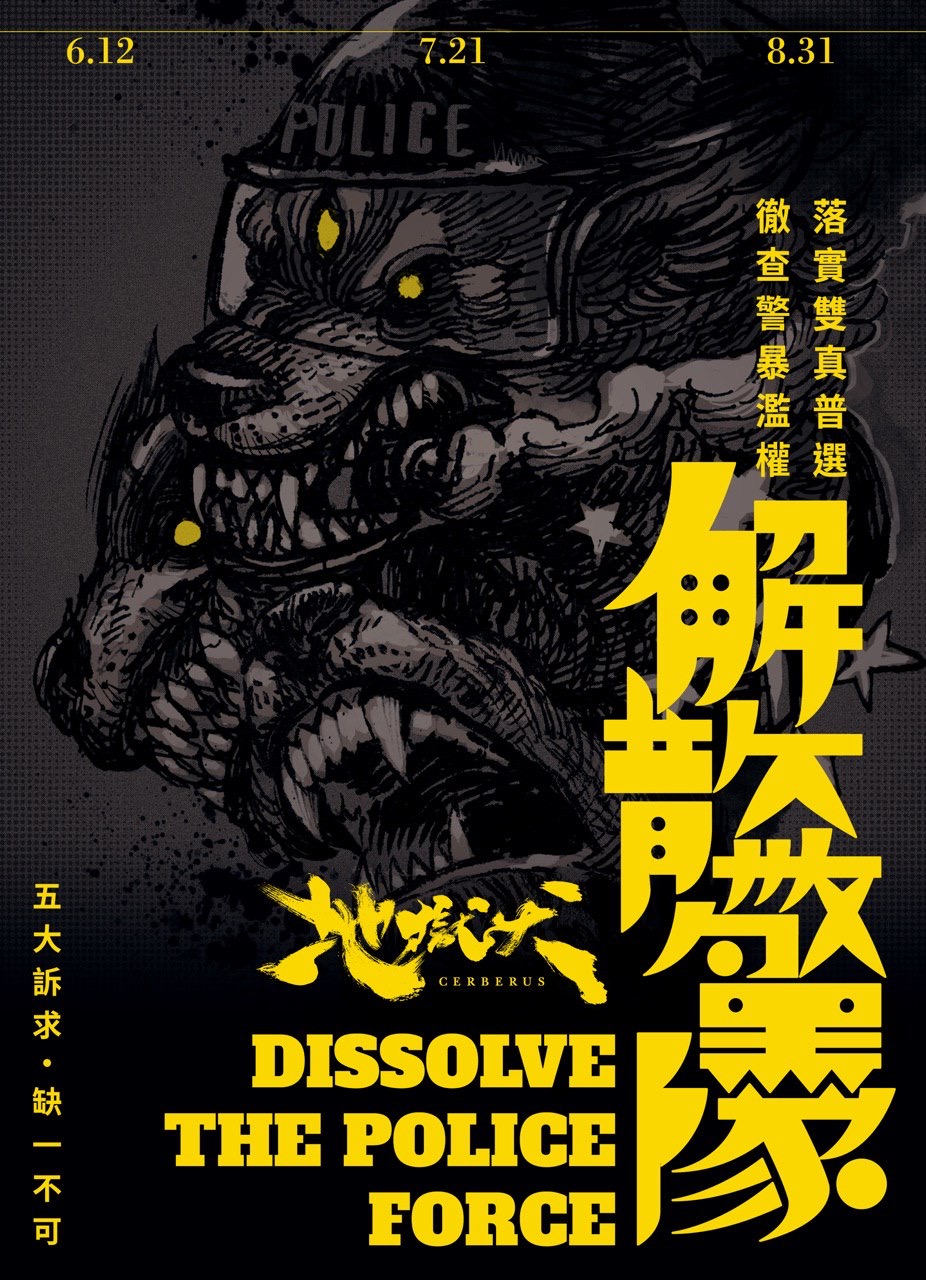

One of many anti-police graphics distributed in the movement.

It seems helpful, by way of a popular forum post, to elucidate exactly what this strategy entails. We quote at length:

We’ve talked about ‘Flash Mobbing the Doghouse’ from August 5 until today, but when the fuck have we actually flash mobbed? Every time it becomes a standoff, waiting for the dogs to surround us, does everybody understand that we’ve already fucked the dogs over the moment they put on shields and gear. Once we lure the dogs out, we should know to scatter immediately, they have to hold the road for 3-4 hours before they can reenter the doghouse, and then have to de-gear, write reports, that’s what’s fucking meant by fucking over dogs: mental torture! Once it becomes a standoff, once someone gets arrested, they will bring him into the doghouse to work off their anger; fucking over dogs is about keeping them pent-up without release[…] Being without organization or leadership is our greatest strength. All we need is to ‘genuinely Be Water’, not be impulsive, scatter immediately once the dogs gear up, that is the highest level of fucking over dogs.

Lure them into attack, then leave them behind. This is the simple physics used to block the economy and tie up police resources.

It’s late by now, and we’ve been in the streets all day. We go home to take a breather and crack open a beer. When we enter the apartment: a group of older comrades has gathered inside to watch the events of the night on livestream; they cheer loudly as we enter. As the momentum heats back up, we decide to hit the streets again. This time, we don’t have to go far. We walk about one block when we see a group of youth running in our direction. We advance cautiously in the direction they were running away from, confident that we pass as innocent tourists. We go up a little bit further and the situation is tense: a first aider is being arrested, and the dogs are brandishing their batons against a small crowd. When the Raptors charge in, the small crowd chaotically breaks off down multiple dangerous streets. As we run, a comrade pulls us off the street and into an apartment stairwell. We run ten stories up and exit onto the rooftop. Here we can relax and enjoy an aerial view of the revolution unfolding all around us. From this perspective, we can see that every road leading into the neighborhood has been blocked. Cars are honking incessantly, and many people have left their cars in the middle of the street to join the crowds. From the ledge of the rooftop we shine lasers at the cops below and laugh when they look to find its source. The mood is ecstatic and fearless, it is the hour of revolt, and everyone can taste it. The cops are forced to retreat behind giant shields into their doghouse by 4 am. At a press conference two days later, police superintendent Yu Hoi-Kwan says that “some protestors were pretending to be civilians.” She later admitted, however, that “it was difficult for police to differentiate between reporters, civilians, and protestors.” That night the police barricaded themselves inside, and we controlled the streets.

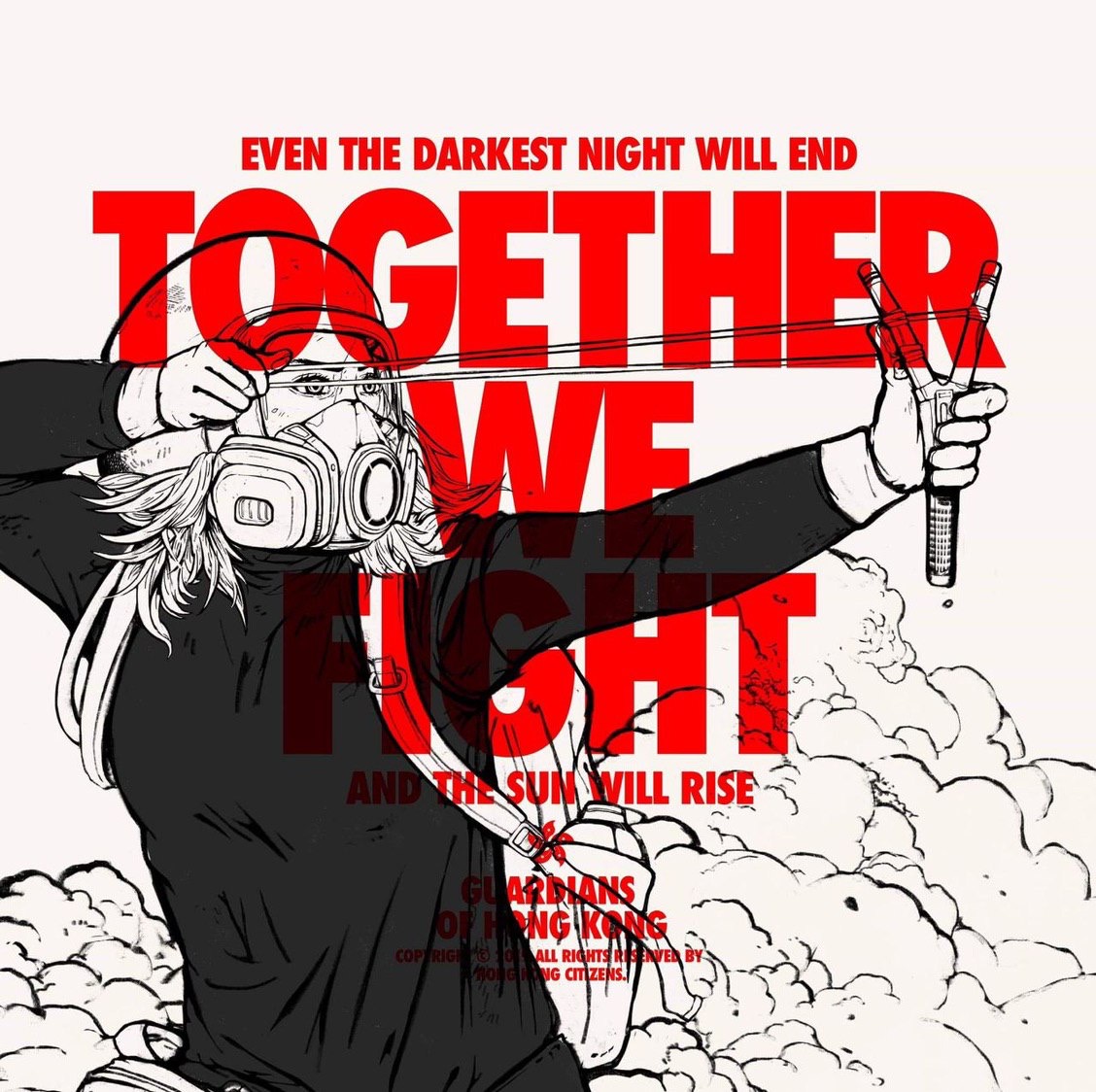

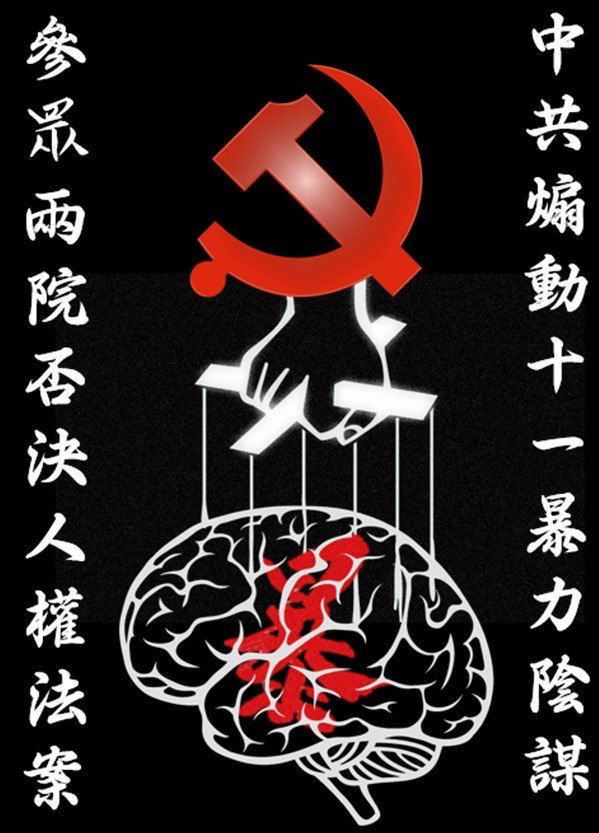

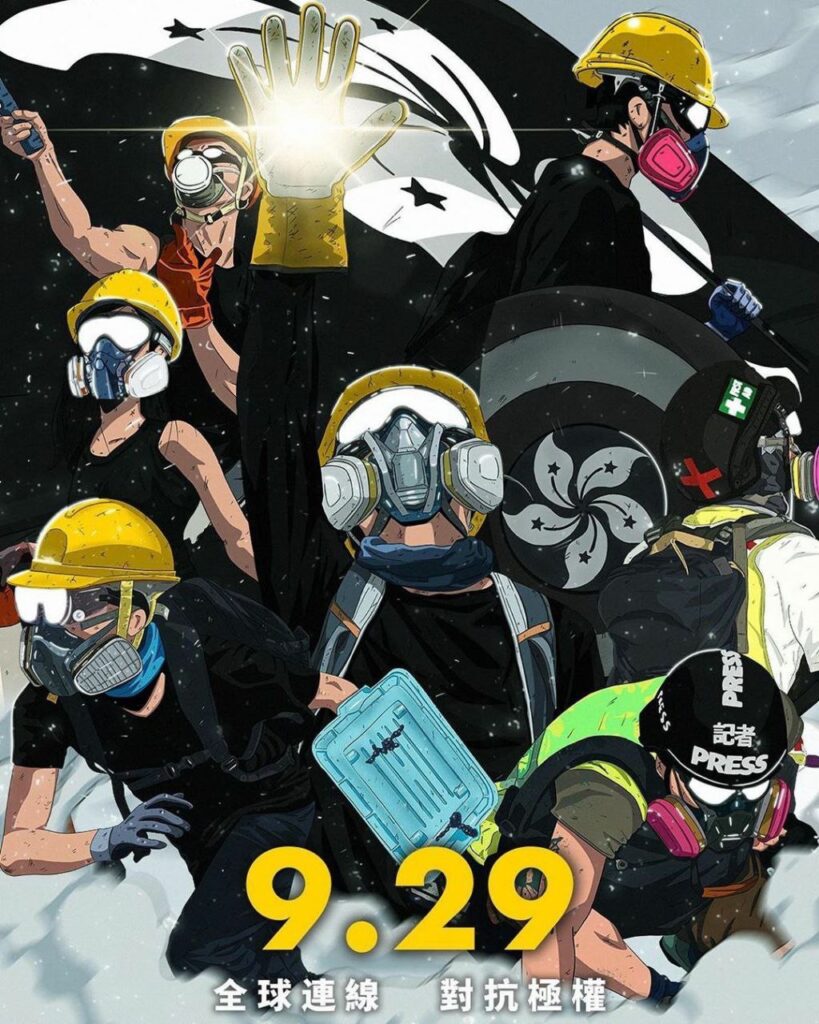

Another poster produced by the protestors, the bottom text reads: “The entire world connected, opposing totalitarianism”

5 – YELLOW HELMETS, YELLOW VESTS, BLACK MASKS

The movement in Hong Kong shows us something very essential about the future of revolution: not everyone will be there for the same reasons. We will find ourselves in Unholy Alliance. Movements like this, which challenge the traditional categories of left and right, will continue to happen as the present organization of the world collapses. We need to develop partisan procedures for engaging with these movements and cultivating discursive, technical, and infrastructural leadership. If we’re not engaged from the beginning, we run a very real risk of ceding the popular impulse to reactionaries.

We are undergoing a long-term transition into an era of disruptive technology and shifting geopolitical arrangements, compacted by a climate emergency which promises to alter the way we live our lives forever. Whatever comes next will be much, much different than the revolutions leftists nostalgize. We are still in the beginning of this shift. The age of anarchy is far from over; it has always been here, sequestered beneath a thousand failed nation-states, those vacant constituencies of aging industrial behemoths, or techno-feudalist warlords dreaming of blasting off into space. In the face of this we understand that everything really is up for grabs.

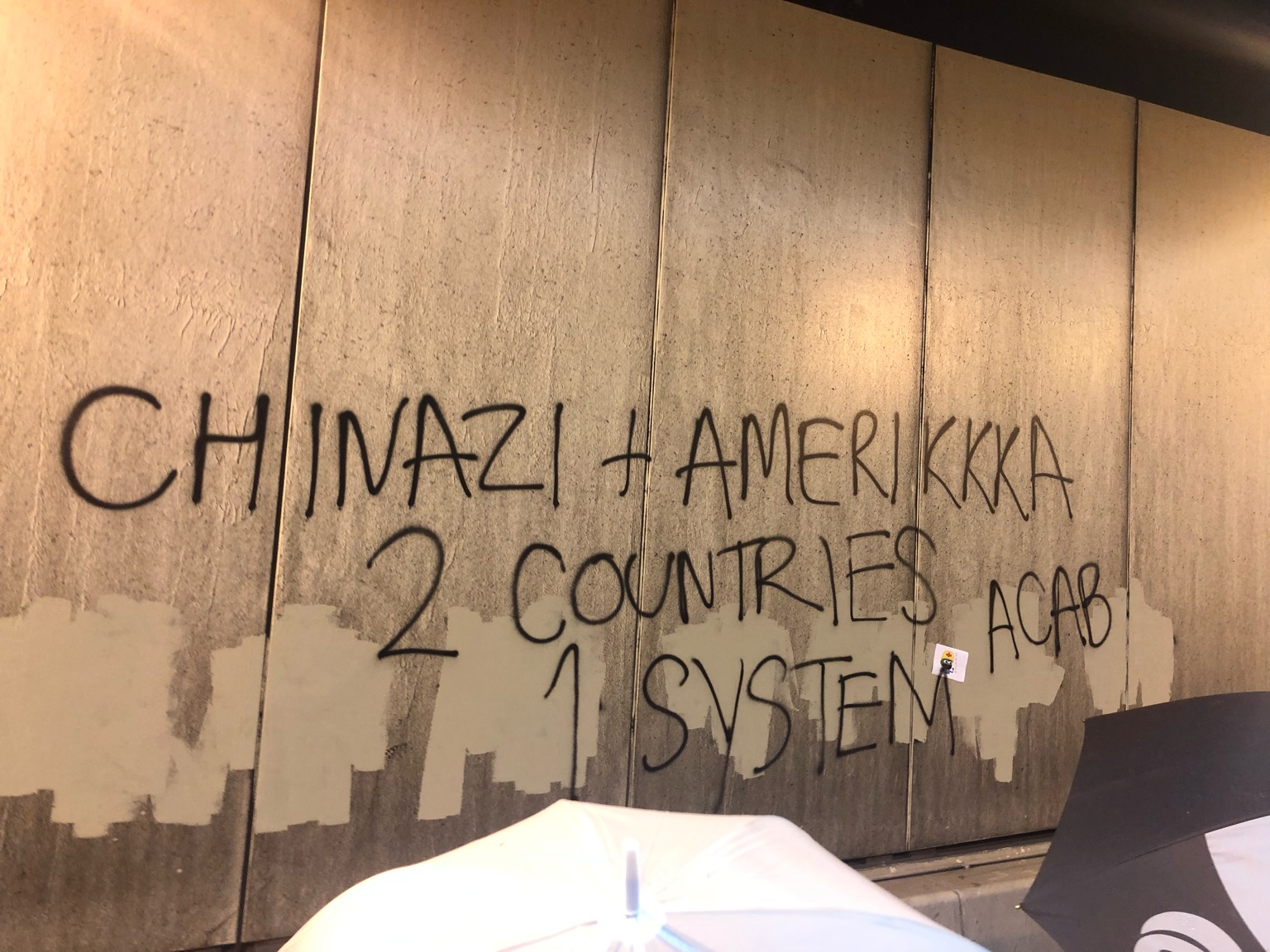

The techniques used in the protests in Hong Kong must surpass the need to fight against the police and be used to build a different way of living entirely. There can never be a revolution “inside” Hong Kong, only out of it. China controls its resources. This is the ultimate contradiction of the struggle in Hong Kong: the revolution can only be completed with the help of people in the mainland. The movement’s inward focus is its biggest weakness, which “prevents them from looking across the border to find their natural allies in the rioting migrant laborers of the Pearl River Delta.”[iii] We need to be able to see our situations nonlocally. Communists fighting against democracies in the West should be able to identify with pro-democracy activists fighting “Communism” in the East, recognizing each other as partisans of the same struggle. Places at the edge of the former Socialist Bloc, like Hong Kong, or Ukraine before it, are especially important for international partisans to engage with. Movements that unfold in these contexts are susceptible to nationalist impulses as a means of counter-identifying with totalitarianism. Revolutionaries fighting against borders and nation states must find ways of identifying with these struggles to prevent opportunistic right wing forces from establishing even more repressive regimes.

As with the Arab Spring, leftists may dismiss the movement in Hong Kong as merely a struggle for “democracy.” But movements will not always fit neatly into established discourses. As friends wrote at the beginning of the Yellow Vest movement, “whoever satisfies themselves with their political ideology is condemned to perish. This is the terrible lesson of the twenty-first century.”[iv] Nineteenth and twentieth century ideologies will instruct but not determine the content or the form of the emerging disarray. From the margins of proletarian life, new hypotheses will emerge for resolving the impasses of the present, and in most places they will be rolled out in unrecognizable costumes and empty slogans. If we are always looking for what we expect, evaluating these movements based on preconceived ideological criteria, we will never be privy to their most unique and singular advancements. We will miss that which is entirely new and unbelievably complex, born of singular circumstances.

CODA

A MESSAGE TO THE YELLOW HELMETS

Hong Kongers: you are so brave, and we stand with you in your fight for liberation. But we come bearing a message of caution. The American government – the ‘democracy’ it supposedly represents – is as bankrupt as the CCP. In our country, you will find no justice, as so many of us discovered during Occupy Wall Street, in Black Lives Matter, and on the plains of Standing Rock. We too are gathering our forces. Like you, we have risen against an absent future, been tear gassed in the shopping malls we grew up in, been tortured and humiliated in police dungeons. We too have tasted victory, if only for an instant. We have built barricades and freed our friends, set fires and made history. We admire your determination and your relentlessness, your capacity to care for one another so thoroughly. Your courage gives us hope and momentum, clarity and confirmation. The scale of your movement, its technical ingenuity and its creative joy will continue to amaze us for years to come, and we will share its secret tactics to revolutionaries here. You have shown what is possible when millions of people collaborate amidst emergency, defeat and catastrophe to fight for their lives against all odds.

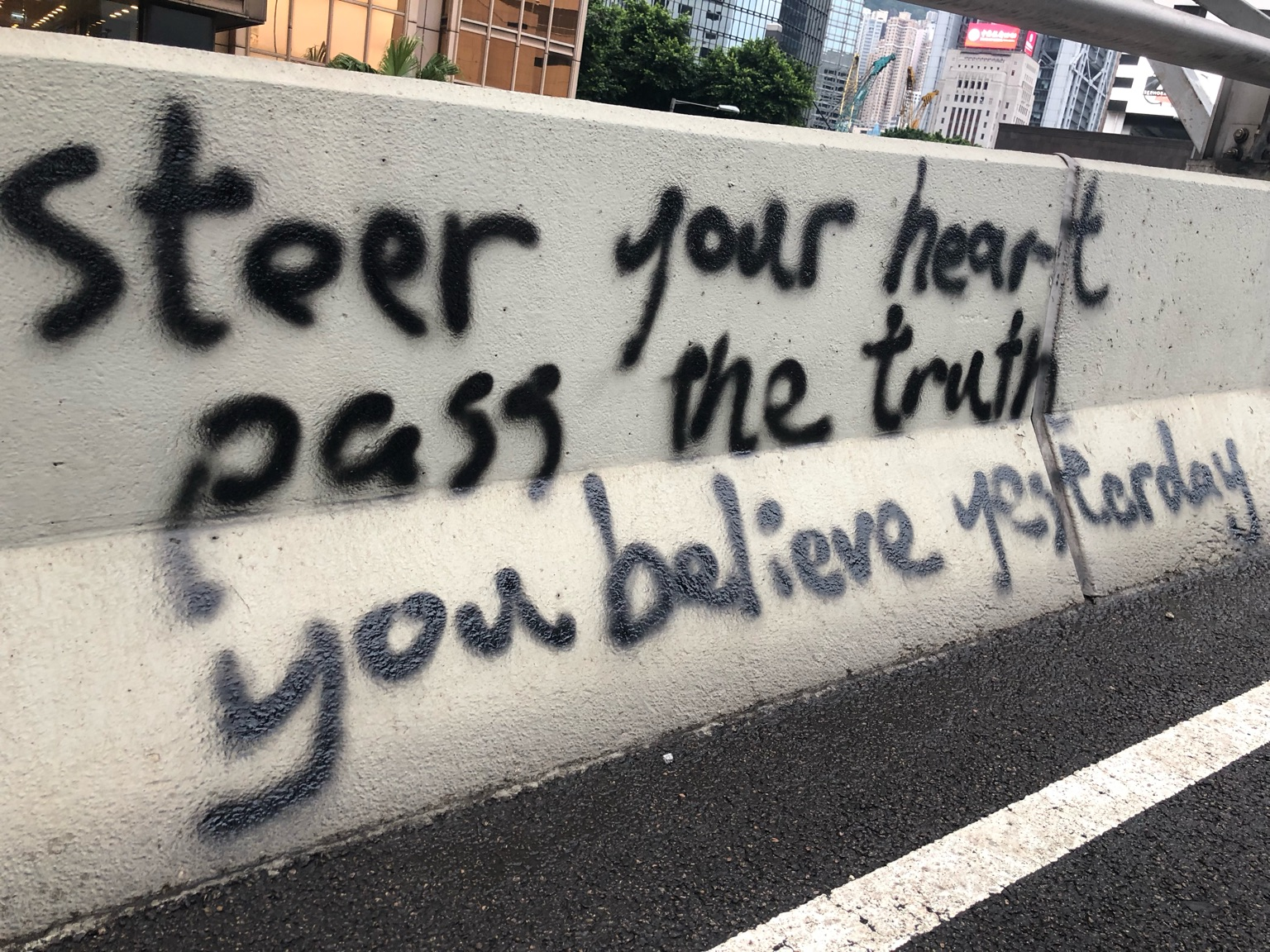

We stand at your side against all police and all governments, whether capitalist or socialist, fascist or democratic. From Chile to West Papua, from Sudan to Hong Kong, from Puerto Rico to Okinawa, in Kurdistan and Chiapas: the people have chosen. Hong Kongers, your fight is not over yet, this will not be your last battle. There is no way to regain the Empire’s grace that would restore Hong Kong to glory. Western democracies are collapsing, and America has certainly never been ‘great.’ Let’s keep our sights set forward and steer our hearts past the truths we believed in yesterday.

As for all of us, it seems our revolutionary imagination is trapped in an anachronistic framework which, ironically, doesn’t go back far enough. As the sea rises in the Pearl River Delta, your struggles, like all others, will become ecological struggles, fighting for access to food, shelter, medicine and water. We will not struggle to win negotiations with governments but rather to fashion collective forms of living that are not catastrophic, and which offer us a vision of the good life: We must fight and we must win. Youth of Hong Kong, you’ve taken us to the furthestmost place, and we look to you in the struggles to come.

And if you burn, we burn with you.

Written 7-14 September with updates on 3 October

In memory of the martyrs of the movement.

Mr. Leung Tsun Kit (35 years old) – June 15th, 2019

Ms. Lou Yan (21 years old) – June 29th, 2019

Zhita Wu (29 years old) – June 30th, 2019

Mrs. Mak (28 years old) – July 3rd, 2019

Mr. Mui (32 years old) – July 5th, 2019

Mr. Fan (26 years old) – July 22nd, 2019

Mr. Kwok (25 years old) – August 27th, 2019

Mr Gei (16 years old) – September 2nd, 2019

Chan Yin-Lam (15 years old) – September 19, 2019

Chow Tsz-Lok (22 years old) – November 8, 2019

And all those unnamed

Notes

[i]The Moral and National Education Law saw the reformatting of Hong Kong’s school curriculum to emphasize national unity and the mainland political system, while disparaging Hong Kong’s tradition of liberal democracy. The Electoral Reform began the process of restructuring the Hong Kong political system. While many hoped that it might open the door to “universal suffrage” (i.e. full general elections with no seats appointed by the mainland and no process of mainland approval of candidates), in fact the reform process only saw Beijing harden its control over the upper echelons of Hong Kong politics. Both were important precursors leading up to the 2014 Umbrella Movement.

[i]Lo Mei Wa, “Letter to a Future Daughter on the Occasion of the “Fishball Revolution”, Guernica, 29 February 2016. <https://www.guernicamag.com/lo-mei-wa-letter-to-a-future-daughter-on-the-occasion-of-the-fishball-revolution/>

[ii] “The Symbology of Revolt” Furio Jesi. Seagull books, 2014

[iii] “Black Versus Yellow,” Ultra, Oct 3, 2014. <http://www.ultra-com.org/project/black-versus-yellow/>

[iv] “Paris / November 30, 2018,” Liaisons, 20 February 2019. < https://en.liaisonshq.com/2019/02/20/30-novembre-2018-paris/>