Translation of an illustrated piece recently circulated among electronics workers in the Pearl River Delta, followed by a commentary by Victor Grant. The Chinese version (马克思来到富士康,他惊呆了!) was originally published last spring on WeiGongHui (微工荟 — “WeChat Union”), an independent platform of news and analysis by and for young migrant workers in southern China.

After more than a century, why are workers still living in such misery?

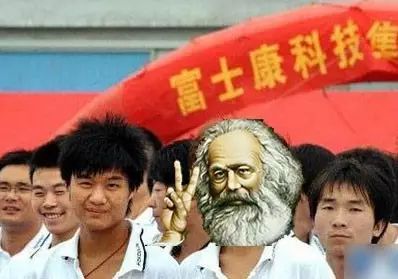

Today is a special day: it’s Karl Marx’s 199th birthday. He has traveled through time to the present and come to Foxconn. Let us know if you see him!

Today is a special day: it’s Karl Marx’s 199th birthday. He has traveled through time to the present and come to Foxconn. Let us know if you see him!

On the 5th of May, 1818, Marx was born into a lawyer’s family in the German Confederation, but when he saw the rising tide of the 19th century labor movement, he chose the working class and dedicated his life to their cause. He predicted the crisis of capitalism and the advent of socialism.

But after the socialist revolution…

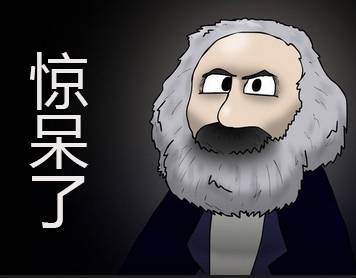

“OMG!”

“Oh my! It’s one thing to get rid of the bosses, but quite another to eliminate this repugnant system! We’ve still got a long way to go before the workers are truly liberated.”

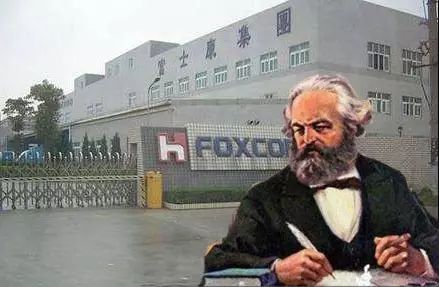

Marx decides to set aside his writing for a moment and go visit the world’s largest processing plant: Foxconn.[1]

- Interviewing for a job

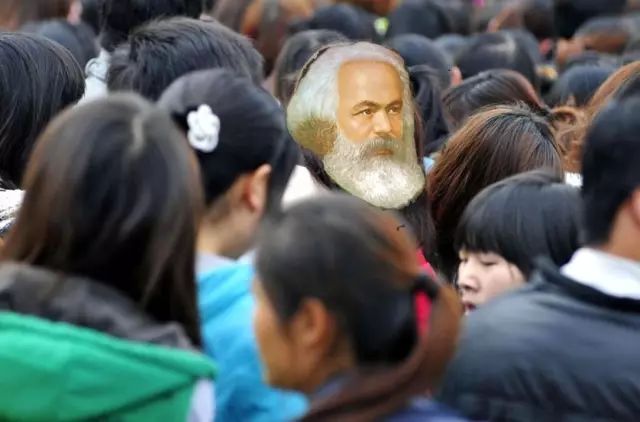

Amazing! There are so many people, many more factory workers than in Victorian England.

Marx joins the ranks of workers and becomes one of them.

Is this a physical exam or the quality inspection of a commodity?

They say, “Anyone who comes here is a Foxconn person”[2] — do you take me for a fool?

- Foxconn, I’m here!

This dorm, why do I think it looks more like a prison?

Why does everyone look so cold? Aren’t workers supposed to be friendly to one another?

Some of the dorms are so filthy and messy!

- On the way to work

Since they live far from work, the workers have to get up by 7 a.m.

The streets are flooded with people!

Marx thinks, “With this many workers, what kind force would arise if their individual powers were consolidated into a movement?”

He swipes the card, enters the factory, and is about to become an actual worker.

- At work

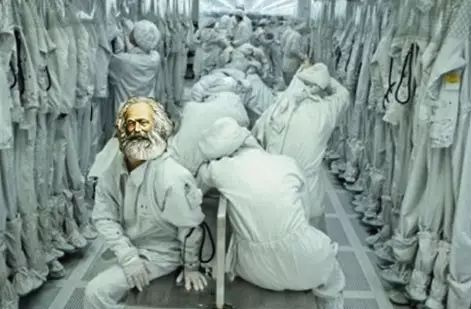

Marx is assigned to work in a dust-free workshop. How advanced! They had nothing like this in Victorian England. But the suits are so uncomfortable. Can you even recognize which one is Marx?

Marx is tired from working. He’s finally given a break, so he can get some fresh air and rest for a moment.

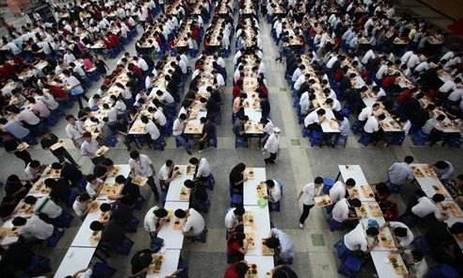

- Time to eat!

What an enormous dining hall!

But the lunch is disgusting…

Still, it’s nice to eat together with fellow workers.

- Back to work

With some effort, Marx obtains approval to be relocated to another workshop.

“Like a turnip in every hole” (一个萝卜一个坑), the work process design and division of labor are much more sophisticated than 200 years ago.

But this optimized division of labor makes you more exhausted, and it’s harder to find a chance to catch your breath.

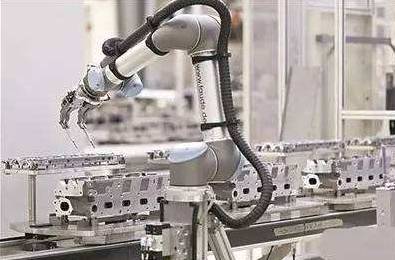

He finally gets to see the legendary robots. But now that workers are cheaper, the company would rather let the robots take a break while the workers continue to slave away. This damn boss! (他老板的)[3]

- After work

It’s 8 p.m., finally time to clock out! He gets a taste of emancipation the moment he swipes his card.

Everyone is bored, so they decide to go to the Internet café together. But the café is even more boring. What the hell is League of Legends? Some new form of opiate?

Marx would rather research how to organize people or write articles for WeiGongHui.

- Repeat

Repetition: day after day, year after year, it’s as if Marx has seen the workers’ entire lives.

“Yes, this is alienation! The boss has turned the workers into boring labor machines.”

It is not only the few actions they perform at work that get repeated. Getting up early, brushing their teeth, eating breakfast, going to work, eating lunch, getting back to work, eating dinner, again back to work, sleeping, and then, the next day, entering another cycle of repetition. Day after day, year after year, even generation after generation.

We cannot stay silent like this. No matter how uncertain we may feel, we must be like Marx and boldly speak out!

Marx can’t help but think: how on earth can the scene he portrayed in Capital still remain unchanged after more than a century?

But something has changed: Now there are more workers, so their power can grow stronger.

“There has never been a savior, we cannot depend on gods or emperors. / If we want to create good fortune for humankind, we must do it entirely on our own!”[4]

“We want you! To give written expression to workers’ voices. Address submissions to…”

Commentary by Victor Grant

Marx’s arrival on the Foxconn factory floor gives comical expression to a sensitive question that has long haunted China: where is Marx in the largest economy still ruled in his name? This playful thought experiment conducted by a group of activist factory workers stands in stark contrast to the official propaganda repeated by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), whose leadership insists that China remains socialist in some sort of Marxian sense. For example, at a celebration of the CCP’s birthday two years ago, Xi Jinping asserted, “The whole party should remember, what we are building here is socialism with Chinese characteristics, not any other –ism.” This stance is coherent with the party’s developmentalist perversion of Marx that children are forced to memorize in school. The CCP reinterprets Marx to justify China’s blatantly capitalist features as necessary for “the primary stage of socialism” and then denounces any other reading as inappropriate for China’s “national conditions.”

Forty years after Deng Xiaoping’s “Reform and Opening” initiated China’s reincorporation in the global economy, the commodity form seeps deeper into all spaces of social life, from wages to housing, to healthcare and education, to shopping malls and shared bikes. In this context, a handful of young workers exposed to Marx’s writings and alternative readings of them have begun to wonder: “What would the old man think” about their present reality?

Forced to work under alienating conditions for the money they increasingly need just to survive, these workers surely fit Marx’s idea of a proletarian “class in-itself,” but many activists and academics have expressed frustration about workers’ continued failure to become a “class for-themselves.”[5] They strike only for narrow economic grievances related to their specific workplace and rarely assert a broader class-based perspective. In this sense, it may seem that the prospect of a Marx-inspired movement is nowhere to be found.

This cartoon is part of a different story. It helps to show that Marx and his ideas are still alive in China, and that the meaning of his writings is highly contested.

Recently the CCP has tried to tighten its authority over how Marx is interpreted, with the Central Committee’s “Document Number 9” instructing party members to silence anyone who questions the “Reform and Opening and the socialist nature of socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

It should come as no surprise, then, that alternative readings of Marx are suffering increased repression. Last November four young activists were arrested for participating in a Marxist reading group at Guangdong University of Technology, and four other members of the group were forced into hiding to avoid the charges of “gathering crowds to disrupt social order.” The group’s activities grew beyond reading and expanded into activities aimed at fostering relationships between students, campus workers and other proletarians in the surrounding community. While it was probably the latter activities that were the more immediate impetus for the crackdown, it was Marx’s writings that provided the group with a sense of purpose and direction. As one observer wrote, “Though the state promoted an ‘official’ version of Marxism as an ideological tool to justify its authoritarian capitalist rule, these activists found in Marxism something quite different: a powerful lens to make sense of class inequalities and oppressions, to which they had already been sensitized, and to fight the system producing these inequalities and oppressions.”

This was not an isolated incident (a similar crackdown on a Marxist reading group occurred in Nanjing a few months earlier), nor are such alternative readings of Marx limited to academic contexts – as illustrated by the cartoon translated above. There Marx takes on a notably different character than the stogie scientist portrayed in Chinese textbooks. He is empathetic and humorous, trying to find ways of helping the workers through direct experience and careful reflection. He delights to eat with his workmates in Foxconn’s dining hall and engages with them at every opportunity he gets. Along the way he finds flaws with everything from the recruitment process to the workers’ obsession with League of Legends.

Radical social critique naturally arises in all corners of society — where one false narrative persists, other explanations crop up. While still unusual, this is not the only case we have observed of young Chinese workers developing sympathies for Marx as inspiration for their struggle. Despite years of neglect and distortion, revolutionary ideas are still available and occasionally discovered by the proletarian denizens of a nominally Marxist state, and some of the striking workers and community organizers find that they are the real communists in town, rather than their washed-up leaders. As one labor activist we talked to put it, “The old revolutionaries were working for communism, and that’s basically what we’re doing too.”

Can the alternative Marxisms we see in this cartoon or these reading groups ever be stamped out by the CCP’s developmentalist Marx? Perhaps Chairman Xi could learn from the old man himself who observed that, “It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but on the contrary their social existence determines their consciousness.” In other words, theories that do not somehow fit people’s lived realities are unlikely to hold for long.

Notes

[1] This is a literal translation of the Chinese. Here, “processing plant” probably means OEM (original equipment manufacturing) plant, and “Foxconn” probably means Foxconn’s factory complex in Longhua, Shenzhen. (Of course, Foxconn is a company with many plants, none of which rank among the world’s largest ten.)

[2] This term “Foxconn person” (富士康人) is a managerial slogan intended to foster workers’ sense of identification with Foxconn, like Walmart’s use of the term “associates” to describe their employees.

[3] There is a pun here that’s impossible to translate. The common equivalent to “damn” is literally “his mother’s!” (他妈的), but here it is rendered “his boss’s!” (他老板的).

[4] Lines from Chinese version of “The Internationale.”

[5] See, for example, Elly Leung & Donella Caspersz, “Exploring workers’ conciousness in China,” Labour & Industry: a journal of the social and economic relations of work, Vol. 26, Iss. 3, 2016.

Translations of Comment by Victor Grant

in dutch:

http://arbeidersstemmen.wordpress.com/2018/03/29/marx-bezoekt-foxconn/

in german:

http://arbeiterstimmen.wordpress.com/2018/03/29/marx-besucht-foxconn/