Image from Trang Quân sự Việt Nam

Guest article by comrades at Đã Thành Đồ Sơn. Follow their blog for news, translations & analysis of capitalism & class struggle in Vietnam.

—–

The Spectacle of Internet Uproar and Celebrity Beef

After the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s July 12th ruling denied China’s historic claims to sovereignty over the entirety of the South China Sea, international social media exploded in support–or in China’s case, rejection–of the decision. Notably, while Chinese state media opted to forego announcing the ruling, Xinhua did declare that the “law abusing” tribunal had issued an “ill-founded award”. Qing Wei Studios, a group with links to the Communist Youth League, put out an awkward video montage weaving manic electronic music, and webcam recordings of Chinese netizens saying “who cares” with b-roll clips of military hardware. The comment section of the YouTube video is a microcosm of the wider internet, with Vietnamese, Filipino, and Chinese internet users calling one another “dogs” in an apparently google-translated nationalist showdown.

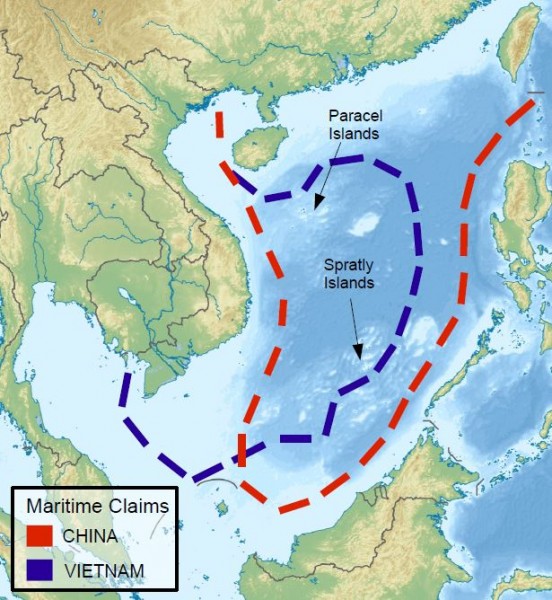

The battle wasn’t restricted to loathsome swarms of internet trolls, but spread to the celebrities of both countries. Pro-China Hong Kong celebrities, many of whom are popular among Vietnamese youth, struck first by sharing a map of China that includes Taiwan and the Nine Dash Line imprinted with the words “China cannot lose even one bit of itself”. Not to be left out, Vietnamese celebrities responded by claiming “Hoang Sa (Paracel), Truong Sa (Spratly) belong to Vietnam” with a map with the South China Sea (East Sea to the Vietnamese) highlighted in red and containing the English word “No!”. Kyo York, a token white-American Vietnamese-language performer, notorious for performing in blackface as Lionel Richie, also dove into the fray. His facebook status defending Vietnam’s “values” was shared nearly 150,000 times.

Concerned Responses

Though some meaningful changes may be in the works, the social media spectacle was not paralleled by a shift in the balance of forces in the region. Vietnam will “sue” China for compensation due a fisherman who had his boat sunk by Chinese Coast Guard ships operating in the area. A lawsuit would be unprecedented, and goes hand in hand with Viet state-media’s new willingness to publish details about Chinese boat attacks and the “cow’s tongue” (nine dash line). These details were once limited to the various illicit anti-regime blogs. Despite this, Filipino and Vietnamese boats are still at risk of being sunk or denied access to the regions in question. Finally, to the continuing dismay of the other ASEAN states Laos and Cambodia have again aligned with China, announcing that nations should negotiate with China individually and outside of the court. Soon after, China reiterated the need for bilateral talks, and compared the South China Sea to an empty parking space being trespassed upon by a conniving neighbor.

That being said, others point out that beneath China’s tough talk, it has in fact quietly adjusted its position in response to the Hague’s ruling, bringing it more in line with UNCLOS, which actually leaves plenty of room for the Chinese to maintain a powerful presence in the region. Furthermore, while the decision directly addressed the Philippine’s dispute over the Spratly Islands, the Paracel Islands are roughly equidistant from Vietnam and China, and much larger, leaving it more vulnerable to an Exclusive Economic Zone claim.

Scepticism toward the ruling has even been shared by pro-American publications worried that the decision has emboldened the Philippines, who are tied to the United States by a mutual defense pact. This gives the Phillipines the ability to drag America into a conflict, a situation roughly analogous to Russia and Serbia leading up to WW1. It’s doubtful, however, that the weak Philippines will seek a conflict with Chinese, instead they’ll likely use the ruling as leverage to try and negotiate some concession from China’s sweeping claims.

Finally, a common leftist position, exemplified by this WSWS article, sees the ruling, like the Trans Pacific Partnership, as part and parcel of a fundamentally American imperialism. While the US government is by all accounts an expansionist organization, myopically focusing upon its hypocrisy is at times neurotic repetition couched in the rhetoric of the anticolonial era. Post WW2 American expansion, though ideologically drawn from 19th century notions of the civilizing mission and progress, was based on a fundamentally international market system that differed from the 19th century metropole-oriented monopoly colony. The common leftist perspective tends to more or less view Russia and China as the last bulwarks against American expansion, or the last nation’s untainted by complicity in American empire, and therefore worthy of some form of “critical support”. Framing the actors in this way forces the author to wait until the final moments before summoning forth the specter of international working class solidarity, needed now to steer the world from the brink of war. Why, where, and how the international working class would come to save the day this time, instead of yesterday or the decades before, remains unanswered.

A Region-focused Approach

Even a cursory investigation into the prevailing economic and social circumstances in the affiliated nations gives us a more detailed, though no less worrying perspective on the recent events. The rest of this essay hopes to provide such a cursory investigation, focusing on Vietnam and China.

First, nationalism is an ambiguous, though pervasive, force in Vietnam. It is the fundamental language through which the party-state is both critiqued and supported. Party propaganda seamlessly weaves revolutionary heroes with prehistoric national myth as evidence of its loyalty to a historically transcendent Vietnamese people– a people defined in opposition to a historically transcendent Chinese colonialism. For the most part, these founding legends are 20th century fabrications and elaborations. It’s difficult to gauge the degree to which these stories are accepted by the population, but it’s inarguable that the Vietnamese Communist Party has egregiously distorted its history throughout all levels of the educational system.

Because of the centrality of this conception of Vietnamese-ness, any failure to oppose “the Chinese” is seized upon by anti-regime activists as a sign of the party’s intention to sell the country [bán nước]. Anti-regime conspiracy theories view Chinese soft-power infrastructure projects, Vietnam-China joint state natural resource extraction ventures, and the South China Sea dispute as a “salami slice” approach to completely annexing the country. State media stokes these fears by exposing Chinese tour guides and rude tourists, or threats that imply Vietnam is a runaway province of China. Furthermore, the Vietnamese state’s refusal to recognize Taiwan as a sovereign state has its popular reflection in a common tendency to conflate Taiwanese capital and the Chinese state. This popular ‘mistake’ is actually vindicated by the fact that this supposedly “Taiwanese” capital had cut its teeth in the Pearl River Delta, and brought veteran mainland Chinese management along in the chase for low wages. This is illustrated by the 2014 anti-China factory riots, in which Taiwanese factories were reportedly looted and burned in anger over a Chinese oil rig settling near the disputed Paracel Islands. Blame for “mistakenly” looting Taiwanese investments instead of authentic mainlander projects cannot be attributed to uneducated but patriotic proletarians who are unable to tell the difference, nor blamed on the party-state who created the discursive conditions for this supposedly mistaken understanding, but instead reflects both a worker revolt against labor conditions more generally, and the deterritorialized nature of contemporary capital, where mainlanders play a significant role in managing Taiwanese and Singaporean enterprises. Alternately, Anner and Liu theorize that East Asian factories were more commonly targeted due to a shared managerial style that is especially unbearable to Vietnamese workers. Whether or not mainlander management played a pivotal role in determining which factories would be attacked, the chain of events testifies that China is metonymically associated with East Asian domination in general.

Lastly, the above mentioned nationalist history predictably involves an exaggerated incorporation of the Paracel and Spratly islands into the natural “Vietnamese” territory. Anti-regime activists are yet to realize what the UNCLOS ruling implies for their territorial claims in the South China Sea, perhaps because the Party’s weakness in opposing Chinese domination over the islands forms the core of their grievances. While cutting off the “cow’s tongue” (reclaiming the South China Sea from Chinese domination) is central to all parties’ platforms, The pro-government (and anti-American) Vietnamese Communist Youth official Facebook was the first to point out that the spirit of the UNCLOS ruling also cuts out the “dragon’s belly” (Vietnam’s maritime claims), a much more ambivalent development for Vietnamese territorial aspirations, and a challenging balancing act for the Party, who has for decades posted signs on every corner proclaiming that the islands “belong to Vietnam”.

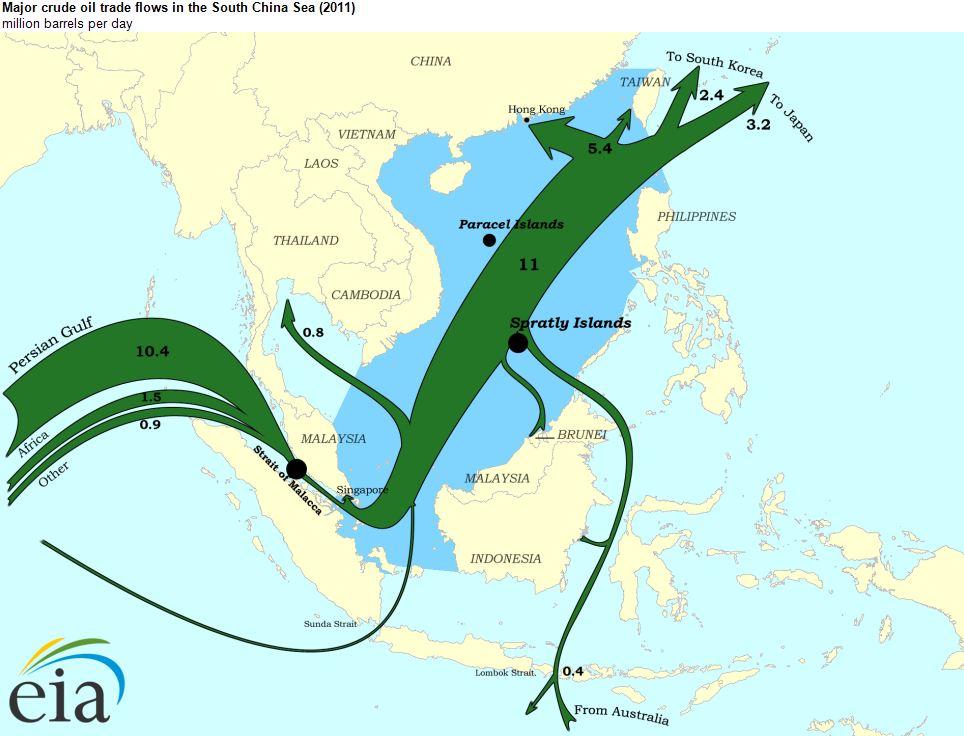

The PCA victory is not a victory for any individual nation-state in terms of gaining validation for maritime claims. Freedom of navigation is first and foremost freedom for capital, a force that recognizes no sovereignty and admits no historical claims. America’s objection to China’s territorial claims is framed in terms of its threat to freedom of navigation, which is ultimately a threat to the free flow of capital. Though many see the United States’ obsessive focus on open seas as a cynical justification for anchoring aircraft carriers within striking distance of the Chinese mainland, this fails to explain China’s sudden determination to annex the region in the first place. The scramble for the South China Sea is first and foremost a reaction to the shifting center of global production. Manufacturing is fleeing China and being blown south along the monsoon winds. The court is not an agent of US empire, but an agent of global capital. While China wishes to ensure its continued stakes in global production, the court’s decision seeks to ensure that goods and capital have an unobstructed path around the crisis ripe Middle Kingdom.

Source: http://pages.stolaf.edu/asiaforecast2014/portfolio/sino-vietnam-relations/

North of the border, China is in the midst of a clear economic downturn. While some are optimistic of China’s ability to bounce back, signs point toward the onset of chronic stagnation, which is bound to lead to rising unemployment and a further growth in already severe social unrest. While the Chuang Journal provides in-depth analysis of many of the factors involved, capital’s hunt for spatial and technological fixes to Pearl River Delta labor unrest is central to the sudden global focus on Southeast Asia.

In perfect tandem with Chinese slowdown, ASEAN has grabbed the baton as the premier global site for FDI, 2013 marked the first time the five largest member countries combined received more FDI than China. The free(r) movement of trade and peoples within ASEAN has not prevented a regional division of labor forming, with older member states like Singapore, Indonesia, and Malaysia responsible for tech-heavy production, and countries like Vietnam and Cambodia dominated by the labor-heavy textile industries. The nature of a constellated system of trade-agreement-bound states is such that they also compete with one another for capital, while no governing body exists to distribute or delimit who invests where. From capital’s perspective, this is a major advantage over the potential meddling of the capricious Chinese state. Furthermore, as AmCham Vietnam makes clear, a lot of the capitalists are specifically fleeing the Pearl River Delta because of rising wages. Proletarian activity is not exterior to the machinations of bourgeois states, nor a saint to be beckoned during desperate times, but is in fact at the core of capital’s tireless mania.

A second factor in China’s unrest is the increasing automation of production. Heeding Xi Jinping’s call for a “robot revolution”, Guangdong province alone has vowed to invest $8 billion on automation between 2015 and 2017. While China’s rapid, export-fueled, national development is the envy of many Southeast Asian and African nations, the dropping costs of industrial robots aren’t only a concern for Chinese workers, but may spell disaster for Southeast Asian nations who are seeking replicate the Chinese experience, especially Vietnam. The ILO, for example, claims that 84% of Vietnamese textile workers’ jobs are at immediate risk from “sewbots”. While they advise that nations at risk need to increase investment in “human capital”, how countries like Bangladesh and Vietnam should fund these investments is not clear. Automation is already encroaching on manufacturing in Indonesia, where, as FT relates, one Japanese factory in Batam received 3000 in person applicants for 80 positions. The crowd was so large that the executives mistook it for a labor protest. If these hypotheses are in fact borne out, then Vietnam’s industrialization push will be stillborn, and workers on all sides of the disputed islands will find themselves increasingly marginal to the global production process.

The South China Sea and the TPP are critical to the process of partially deindustrializing China. Though invited, China is unwilling to sign on to the TPP because of marginal potential for profit and its serious challenges to member state sovereignty. Japan and four ASEAN countries are firmly committed, with Korea and Taiwan both seeking entry. The TPP is wildly popular in Vietnam, which will see a massive boost in exports through the arrangement. Wealthier countries like Korea, Taiwan, and Japan will take further hits to labor in agriculture and manufacturing, while increasing profits for native MNC’s who are already outsourcing and hope to continue to do so. It’s worth mentioning here that despite Vietnam’s love for American aircraft carriers in the South China Sea, and their fanatical love for Obama, American capital plays a relatively small role in the country. The largest investors are Korea, Japan, and Taiwan, in that order. While the USA is doing all it can to “pivot towards Asia”, and towards Vietnam specifically, it seems erroneous to paint this story as one of American imperialism, or neocolonialism. A Vietnamese factory worker is more likely to face off with Chinese, Korean, or Japanese capitalists, but she is also more likely to listen to Korean pop, occupy her child with Japanese cartoons, or enjoy a bubble tea while watching Journey to the West on her Oppo phone.

Source: https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.cfm?id=10671

War?

Still, beyond the potential damage dealt directly to American trade, Chinese control over the South China Sea would to some extent entail Chinese control over Korean, Japanese, and Taiwanese capital. These three countries are longstanding American allies, and it stands to reason that should China be determined to dominate the South China Sea as a territorial water, thereby dominating one of the most important shipping lanes in the world, an American allied coalition may be dragged into conflict.

First we should make clear that an America-China war would be catastrophic for the global economy. America is strongly incentivized to mediate rival claimants and prevent conflict. Though “pivot towards Asia” is still widely used by commenters, it’s worth mentioning that the American military strategy in the South China Sea is now called “Asia Pacific Rebalancing”, which, as the name suggest, focuses on empowering American allies to defend themselves against China. Though there is a mutual defense treaty between the United States and the Philippines, no such expectation for American protection exists for Vietnam. The war between these two nations would likely be a limited naval engagement, featuring China inundating military targets with high volume long range missile strikes coordinated alongside electronic attacks on communications, seeking to destroy as many Vietnamese naval and economic assets as possible in order to “teach it a lesson”. There is no real benefit to invading the Vietnamese mainland. Vietnam, in turn, would probably seek to use its submarines to attack shipping lanes and ground targets. Even a couple sunken container ships would entail significant economic losses through deterrence and ballooning insurance costs.

Besides dying as soldiers in war, or dying through the destruction of civilian infrastructure in missile or bomb attacks, one significant negative impact on working class organization would be an epidemic of feverish nationalism. If, as Joe Buckley wrote in 2014, the South China Sea dispute functions primarily as a convenient distraction from Vietnam’s pressing domestic issues, a shooting war would give the party carte-blanche to fiercely crush any dissidence. A scary thought considering how heavy-handed they are in peacetime. The Hague’s ruling has already done much to drown out anger at the government over their handling of Formosa steel plant pollution scandal, even as Formosa unbelievably finds itself in a second pollution scandal, this one with clear signs of local-government collusion.

Another possible outcome is that the two countries’ Communist Parties collapse after a pair of humiliating military defeats. While some may see the potential power vacuum as a golden opportunity for worker organizations to seize power, Vietnamese workers are ill prepared to rise to the occasion. While both parties are irredeemably reactionary, it’s hard to imagine a progressive force taking over during jingoist pogroms with likely backing from the CIA, who would seize any opportunity to install friendly governments in the area.

Conclusion

In sum, despite the explosion of media attention, little has actually changed after the Hague’s ruling. However, barely hidden behind the rhetoric of American imperialism over a historically transcendent Chinese territorial integrity, a reshuffling of the spatial coordinates of global production is taking place. As the adage goes, the more things change the more they stay the same. The strait of Malacca will continue its more than 500-year reign as one of the major arteries of global shipping. The difference today is that emerging consumer markets in East Asia will begin drawing more and more from a Southeast Asian manufacturing base. Therefore, Chinese military proximity to SE Asian industrial centers doesn’t only threaten the west side of the strait, if China dominates the South China Sea, it will be that much closer to dominating emerging East Asian capital. A domination that the other nations may not take lying down. War, however, has to be seen as a serious danger for the working classes of Vietnam and China, not so much because of the risk of fatality, which would hopefully be minimal and limited to professional navies, but due to the opportunity it presents for co-opting and crushing labor organization on an unimaginable scale. Vietnamese proletarians, if they can overcome nationalism, have much to gain from the experience of Pearl River Delta workers. Not only because capital tends to homogenize the experience of labor, but also because both groups are working at the very same companies, sometimes managed by the same individuals. With the “economic escalator” of Chinese/Korean style development foreclosed due to the increasingly low cost of industrial robots, Vietnam’s other ‘development’ options look bleak. Building Viet-Chinese proletarian cooperation is a longshot, but a war would seal off what little opportunity is left.

A critical note in the presentation of this article in abridged form at the Netherlands blog arbeidersstemmen.wordpress.com :

The article by the group Dja Đồ Thành Sơn also develops on the usual position of the bourgeois ultra-left, for example, most Trotskyists. These see the court ruling as a smart move by the Americans against Russia and China, which they regard as the last bastions against imperialism. The article points rejects the “critical support” of China and Russia, which follows from that reasoning. However, the article opposes this with a very weak reasoning:

(…) “summoning forth the specter of international working class solidarity, needed now to steer the world from the brink of war. Why, where, and how the international working class would come to save the day this time, instead of yesterday or the decades before, remains unanswered ”

The point is that the leftist bourgeois positions, from most anarchists Trotskyists to Maoists and Stalinists, are simply waving the banner of anti-imperialism and international solidarity to lure workers in reality under the national flag. In some cases by he formation of fronts with the ruling pro-Chinese and / or pro-Russian factions of their own bourgeoisie (eg Laos and Cambodia), in most cases by forming a front with oppositional bourgeois forces which represent another foreign policy (eg Vietnam or the Philippines). When it comes to the real international solidarity as expressed itself in the resistance of workers against the First World War, a resistance that culminated in the revolutions in Russia and Germany, then we must conclude with regret that this subsequently has not repeated itself on a massive scale. But that makes the lessons we can draw from this historical experience, no less important.