Beyond its massive economic impact, the recent coronavirus outbreak has also raised important questions about the nature of China’s healthcare system. Elsewhere, we plan to review some of the basic facts about public health expenditures and the comparatively expensive, inefficient quality of healthcare in China. But it’s impossible to understand these issues without first understanding the character of the broader “social insurance system” (社会保障体制), of which healthcare is one part. This system is known for its long-standing financial deficits, its built-in geographical inequalities (which privilege wealthy coastal cities), and the vast divide between legal obligations on the part of employers and the de facto practice of widespread non-payment into the social insurance fund.

China technically has five types of social insurance, including the pension fund, medical insurance, unemployment, maternity pay, and work-related injury insurance. These are accompanied by a “housing fund” designed to encourage employees to save money to purchase a home. They are generally referred to together as the “Five Insurances and One Fund” (五险一金). The pension, medical and (usually) unemployment insurance technically require payments from both employer and employee, while the maternity and injury insurance are paid into by the employer alone. The housing fund is paid by both, but accrues entirely to the employee. All of this describes how these funds would work if employers were to follow the letter of the law. In reality, the application of these requirements is extremely uneven, both between different cities and among firms. This is one reason why unpaid social insurance benefits have become such a major focus of worker unrest in recent years.[i]

There is widespread recognition in China that the incapacity of this system threatens to produce social instabilities in the long term, but legitimate reforms have been piecemeal and insufficient. As was mentioned in our interview with Lao Xie, expansive promises to reform the system to the benefit of its working class recipients were made during the Hu Jintao regime. But, by the time Xi came into power, these were increasingly portrayed as “unreasonable” and the plans were rolled back. Meanwhile, a series of reforms were implemented in the other direction, further defunding or otherwise limiting social insurance access for workers. The most egregious of these efforts have focused on the pension system, explored in the article below. In recent years, for instance, the retirement age has begun to be pushed back, but only a little at a time—“like ‘boiling a frog in warm water’ (温水煮青蛙)”—and regular pension increases to keep up with inflation have been intentionally depressed.

The result is that the best illustration of the contradictions inherent in the system as a whole are presented by the pension system specifically, and we therefore use the article translated here as a general introduction to the broader systemic crisis. The piece below, by Jiang Xia (whose work we have translated previously), emphasizes the ways in which historical inheritance, economic pressure and demographic trends have combined to produce this wide-ranging crisis in the pension system. Though the emphasis here is on social insurance, the question also lies at the crux of larger demographic debates about whether or not China has passed the so-called “Lewis Turning Point,” after which old workers begin to outnumber young ones (i.e. the “demographic dividend” dissipates) and the social burden of caring for the elderly begins to hinder overall economic growth, while also placing specific familial-financial pressure on the young.

We agree with the author’s major points and analysis here, which are backed up by solid data and insightfully connects the crisis to a Marxist analytic framework. That said, the author, who is a university student within a major city, tends to draw some of the more limited language and conceptual tools common to the Chinese New Left. The piece was originally published on Tootopia (土逗公社), a now defunct clearinghouse for left-wing social theory and cultural criticism from mainland millennials. We find the often archaic and vaguely social democratic approach of both the older, academic New Left and the younger, digital Tootopia current to be an obstacle. As we’ve explained in previous prefaces, such approaches often carry with them strange presumptions about the state’s autonomy from the economy and its capacity to be a force for good—or even portraying problems as rooted in the failure of political leaders in China to be consistent with their stated socialist inheritance. Similarly, they invoke unpopular, incorrect and archaic socialist-era language in bizarre and counterproductive formulations (see the use of “workers and peasants” in the conclusion to the piece below). In some cases, we’ve simply translated these phrases into more accessible versions in English. But overall, the ways in which the Chinese Left—old and young, academic and activist—seems stuck in a ghost world of nostalgic Maoist vocabulary is itself an informative fact. And, in this case, none of these features distract or distort the central point of the piece, which remains salient.

—Chuang

Introduction by Tootopia Editors, February 21st 2019:

Chinese social insurance issues seem to have entered into two difficult situations: On the one hand, business owners complain that social insurance payments place a heavy burden on the enterprise. On the other, the portion of social insurance that covers pensions is not sufficient to make ends meet. In fact, both the private sector and the government have avoided responsibility for today’s pension deficit. Just as the private sector has refused to pay contributions to social insurance funds, the outstanding debt to older workers left behind by the reorganization of the state sector has only intensified today’s pension deficit crisis. At a certain point, pensions will be sacrificed for the sake of China’s rapid economic growth.

On the 19th of February [2019], the National Development and Reform Commission released a report titled “Redoubling Efforts to Fix Shortcomings in Public Services within the Social Sphere, a Program of Action to Advance the Formation of a Strong Domestic Market” (below abbreviated as “the Program”). Regarding elder care, the Program recommends that related services be completely marketized. It calls for the development of private institutions to care for the elderly, allows for the cancellation of existing structures, supports investment into the elder care system on the part of both domestic and international capitalists, and other similar preferential policies. The Program further deepens reforms of the non-profit elder care sector’s system for registering institutions, allowing those institutions that are in accord with laws and regulations to establish multiple branches, allowing them to reach economies of scale, to better interlink, and to build their brands. It further encourages capital that had been used in manufacturing, business or natural resources to be converted into use for elder care services. Finally, it encourages public-private partnerships at the local level in order to further the development of the Program.

In other words, from that day forward, care for the elderly no longer relies on the government, but instead on the market, which is to say that it relies on money.

In the entire Program, we can’t even find any intent to further develop the social insurance system. With the social insurance fund in deficit for many years, it seems that they have finally found a way to dispose of it. In the past, state-owned enterprises threw workers out into society like they were nothing but dead weight, but at least they had social insurance. Nowadays, private enterprise won’t stop talking about social insurance, wanting to again throw it out like dead weight, but this time into the market. In reality, both the government and the private sector cannot avoid responsibility for the burden of the social insurance deficit, because the private sector has not been paying its social insurance contributions in full, and the state left behind a debt to elderly workers during the restructuring of state enterprises. Altogether, this intensified the current crisis of the social insurance system. To a certain degree, we can say that the pension system has been sacrificed for the sake of the Chinese economy’s rapid growth.

Henceforth, care for the elderly will be truly marketized. This makes those of us who will get old before we get rich more and more worried, not daring to think about what we will do when we age. So much so that we fear we might not even be able to live a single day into our old age! How did this embarrassing fact about our pension system take shape? The article below offers an analysis.

What are the Bosses Complaining About:

Do Pensions Encumber the Development of the Enterprise?

By Jiangxia

Originally published January 17th, 2019[ii]

“You want the pony to run, but won’t provide for it in old age.”

At the end of 2018, there were two features of the Chinese economy that everyone was focused on: the first was the so-called trade war between the US and China. Since America is the nucleus of the global division of labor, the trade conflict made clear that this structure may be undergoing some sort of transformation. Under the existing global system, the conflict between each country’s interests is becoming more and more apparent. These are external pressures faced by the Chinese economy. The second feature was domestic businessowners complaining about the economic slowdown, and even “going on strike” due to high costs. The unwillingness of the bosses to invest caused domestic fixed investment to wither. This is an internal contradiction confronting the Chinese economy.

However, this “strike” is not like other strikes. It obtained an energetic response from the state: In November, a conference of private businessowners issued a statement titled “We are proud businessowners.” Soon after, a series of preferential policies were launched to help private companies buy up businesses. So what are the bosses complaining about? In reality, the costs and burdens borne by private businesses exclusively originate from two sources: On the one hand, in relation to the state, the most important costs are the raw materials supplied by state-owned enterprises, the financing received from state-owned banks, and the taxes that they are are subject to. On the other hand, in relation to the workers, the most important burdens are wage and social insurance payments. This article will discuss the burden placed on companies by social insurance payments. Through this analysis, we believe that it will, to a certain degree, be possible to reflect the character of China’s economic development in recent decades and the deep-seated contradictions accumulated in the course of this development.

A Superficial Contradiction

On the surface, China’s social insurance system seems to be a contradictory phenomenon: On the one hand, China’s rate of enterprise contribution to the social insurance fund (i.e. the portion of wages deducted as an insurance premium each month) is said to be one of the highest in the world. On the other hand, the social insurance funds for the nation as whole are at risk of falling short. In other words, although enormous quantities of money are being submitted, it’s still not enough to cover people’s social insurance needs.

Photo by: dramafever

But how high is the rate of enterprise contribution for social insurance in China, after all? To take the basic pension fund (which comprises the largest share of the social insurance fund) as an example: this alone accounts for 70% of the enterprise contributions out of all five types of insurance combined. And within the pension fund, pensions for urban workers compose the vast majority (about 90% of the total). As for insurance premiums, urban workers’ contribution to the pension fund is 28% of the total wage, with about 20% being the firm’s responsibility and 8% being deducted directly from the workers’ individual wage. Concerning questions about social insurance, the expert Zheng Bingwen explains:

Chinese pension payments have remained high. Out of the entire pension system, the pension premium sits above the 22.5% average in the European Union, and is also higher than the OECD-member average of 19.6%. It is even twice as much as the US average, and three times that of South Korea. In terms of the amount paid by the employer, the 20% contribution in China is twice that of France, and three times that of the US and Japan, while being four times that of Canada, Switzerland and South Korea. So the employers’ burden is far higher than in these countries.[iii]

It would stand to reason that the more people pay into pension funds, the more money would be available to withdraw. But from the perspective of China as a whole, beginning in 2015, urban workers’ basic pensions had actually reached unsustainable conditions (after deducting government subsidies at all levels). What does this mean? First, when it comes to the actual operation of our country’s pension system today, it follows a pay-on-the-spot model. In other words, the money that we pay into the system now is not actually used to take care of us in the future. Instead, it’s being used to support those who are already retired. Under this sort of model, then, even though we “pay in advance,” the lack of sufficient funds implies that our generation’s pensions are not enough to support today’s elderly population. It’s enough to drive you crazy. (As for why this is the case, we will discuss the issues of overaccumulation and historical debt below.)

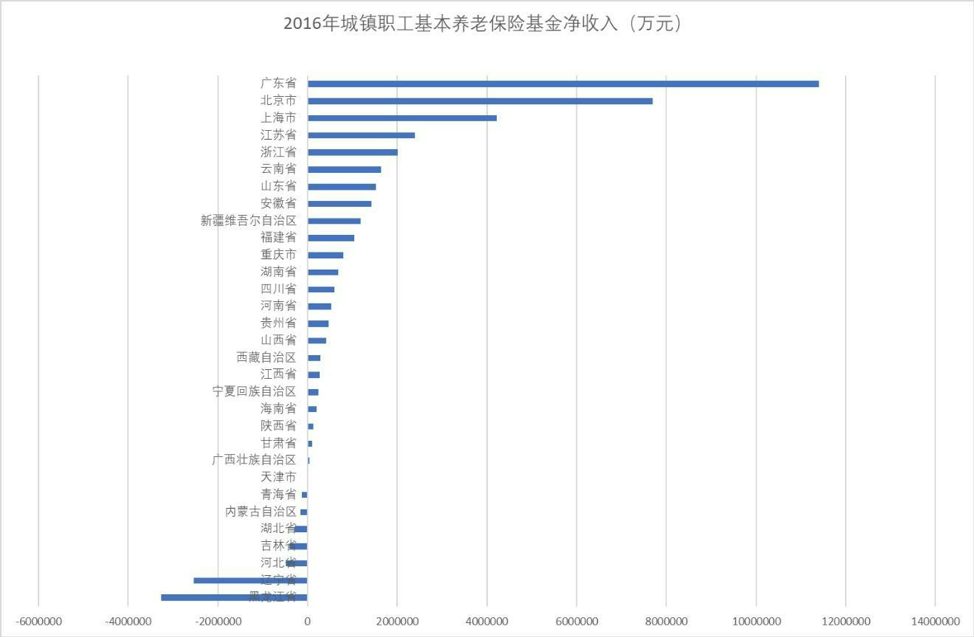

Even more unfortunate, the deficit in the pension accounts for labor-exporting (usually underdeveloped) provinces such as Liaoning is even more severe. This is due to the fact that our social insurance fund is not a truly nationwide system. In many places, the scope of the system barely reaches the county level. Here is an example: say Old Zhang is a migrant from Hebei working in Beijing. His enterprise pays its share of his basic pension contributions into the Beijing accounting system. (Social insurance accounts are divided into overall plan accounts and individual ones, but the overall plan accounts make up the vast bulk of the total.) When he grows too old to work and wants to return home, this portion of his pension cannot return with him to Hebei, but instead must stay in Beijing. Under conditions in which the total national pensions already require a state subsidy to be maintained, this can only intensify the suffering of those who have left their home provinces to work. It’s equivalent to underdeveloped provinces not only donating their labor power to the developed ones, but also subsidizing these wealthier provinces’ pensions. As the following chart shows, among China’s 31 provincial-level units, seven of them are in the red for urban workers’ basic pension accounts, with the most severe being Liaoning and Heilongjiang.

Are Higher Social Insurance Payments a Serious Burden on Private Enterprise?

Many businessowners complain that an increase in the rate of enterprise contribution to social insurance funds would push up costs. In mid-2018, when the government proposed that contributions should be collected more rigorously by the central Tax Bureau, some bosses worried that if they paid all the social insurance contributions that they owed, their films would collapse. (Which is to say that they had never paid in full to begin with….) Does this mean that higher social insurance payments are a serious burden on enterprises? On the surface, it seems to be the case, but we can at the very least offer these two arguments in response:

First, the reason that the nominal cost of social insurance payments relative to wages is so high is that the bosses have set wages too low. The rate of enterprise contribution to social insurance is a relative value, determined by the social insurance payment divided by the wage. So to say that social insurance rates are too high could mean that the absolute cost of social insurance payments is too high, or it could simply mean that the absolute level of the wage is too low. The media rarely mentions the latter, but everyone knows that “Chinese workers have long been synonymous with “cheap labor-power.”

Second, the actual rate of China’s social insurance payments is not at all as high as the nominal figures would indicate, because the majority of enterprises don’t pay the full amount legally mandated. In the first place, we must take into account the fact that more than a third of migrant workers are not even covered by social insurance funds. According to the “Migrant Worker Monitor” report,[iv] in 2014 the proportion of workers participating in the pension fund was no higher than 16.7%, and, although more recent numbers have not been released, it is unlikely that this figure has increased. Migrant workers’ social welfare is hardly protected by the labor law, the labor contract law, or the social insurance law. To a large degree, it is still as Marx says: “As long as capital is weak, it still itself relies on the crutches of past modes of production, or of those which will pass with its rise.”[v]

On top of this, in social insurance payments made by enterprises on behalf of urban workers there exists widespread falsification, underreporting of wages and underpayment of social insurance contributions. The media often cites this figure: Of all Chinese enterprises, no more than 30% pay their social insurance contributions in full. So after it was announced that social insurance payments would need to be handed over directly to the Tax Bureau in a unified collection system beginning in 2019, the problem of high social insurance payments has become a constant topic of discussion because many bosses are worried that they would not be able to conceal anything from the Tax Bureau and they would have to pay in full or else. It is commonly believed that, in its campaign to collect personal income taxes, the Tax Bureau will need to more accurately determine the real wages paid to workers in an enterprise. Its powers will therefore increase, and this will severely diminish enterprises’ opportunities to evade paying their full share of social insurance. The implementation of full social insurance payments will then influence the competitiveness of weak medium and small enterprises, such that the slightest increase in social insurance payments could cause many enterprises to sink into a deficit.

It’s apparent that the allegedly high burden social insurance places on private enterprises is actually already passed on to workers for the most part, and that business owners’ grumblings about higher social insurance payments driving up costs is largely a false presumption. After all, you can’t complain about something that hasn’t actually occurred. This explains why the bulk of China’s medium-to-small-scale enterprises have for many years relied on a system of informal employment, because: under such a system the rights of the workers have no full protection under the law. The moral character of the formal regulations are quite high, with “ensuring that the rights of the workers are earnestly protected” as the bottom line. But for the business owners squeezing as much out of cheap laborers as they can, ignoring labor law and the requirements of labor contracts has simply become the norm. “Ensuring that the rights of the workers are earnestly protected” is for the most part still an unreachable horizon.

In this way, the replacement of informal systems by formal ones has become a normal phenomenon in China. Within the hierarchy of socioeconomic relations, informally employed migrant workers occupy the lowest stratum. They are the main producers of society’s wealth, but they also bear the bulk of the burden of rising costs. Their position is, however, different to that of the environment. The destruction of the environment in the course of economic development threatens the conditions of all social classes, and in reality it’s fairly easy for such issues to obtain attention in mainstream discourse: the issue of Beijing’s smog is one such example. But, by contrast, the fundamental rights of workers are often buried in the evasive language of the free market, and it is very difficult to arouse indignation about such issues across classes.

Photo Credit: Tengxun Video

Is the Social Insurance Deficit Merely the Result of an Aging Population?

The media often blame the social insurance deficit, and in particular the pension deficit, on the aging of the population. This is clearly related to the pay-on-the-spot model used for pensions. Alongside an aging population, the burden placed on workers by retirees is increasing and the pressures on the equilibrium of the pension fund’s cash flow are growing greater and greater.

But did these pension fund problems, seen through the pay-on-the-spot model, just appear out of nowhere? The pay-on-the-spot framework is merely the method for operating the pension system, but the proximate cause—in this case the facilitating mechanism of the system—is not equivalent to the ultimate cause at the root. The aging of the population is simply the straw that broke the camel’s back. Seen from its origin, the pension given to a worker after retirement is just a portion of the value they produced while they were young, not a form of charity for the lower classes. It goes without saying that a society’s pensions are a necessary deduction from that society’s total surplus product, or we could say a portion of the value of labor-power. As repayment for labor, pensions ought to be paid in full, and if a society’s pension fund turns out to be too little, this is actually a sign that the money originally paid into the pension fund has been moved elsewhere. To put it bluntly: if a society’s rate of exploitation is too high, then its pension fund will also be exploited—but where has it gone? According to the logic of an economy maintaining continuous, rapid growth, the main use of surplus product is accumulation. In other words, the pension fund has been emptied by capitalists, the money converted into investment capital. The so-called pension fund deficit is clearly, in essence, the seizure of social insurance funds for investment. And this is a problem brought about by the over-accumulation of capital.

Following from this premise, the significance of the aging population becomes relatively clear. The burden of an aging population is the inverse of the “demographic dividend.” You can’t just force hundreds of millions of workers to contribute their low-cost labor-power and then not provide for them when they’re old. When those hundreds of millions of Chinese workers were still young and green they served as a massive reserve army of labor, and thereby pushed wages and social insurance expenditures down to a very low level. This generated surplus value on a huge scale, which was transferred to both domestic and international capitalists. This formed the foundation for rapid economic growth, while also being the source of the violent, widening gap between rich and poor—this is the reality of the so-called “demographic dividend.” But when these hundreds of thousands of working class people age, or if they get injured on the job or fall ill, the rapidly growing economy doesn’t have enough social insurance funds to take care of them. They’re merely a crop of chives to be harvested by neoliberalism: after being cut down in the spring of their youth, the remainders are simply left to rot back into the earth.

The Historical Debt of Social Insurance

Finally, we will address the other major cause of the current social insurance deficit: historical debts. Although China’s current social insurance system is on the surface supposed to be a combination of individual accounts and society-wide bookkeeping, in reality it’s still the pay-as-you-go system. Everyone’s accumulated capital in their individual account (as their own fund accumulated for their own retirement) is still funneled out to pay for the overall system, effectively emptying the account (even though the funds technically show up “in” the account, they are not really there). Why are these funds shifted out of the accounts in the first place, though? The answer actually traces back to the restructuring of state-owned enterprises that took place at the turn of the millennium. This wave of factory closures caused 20 million workers to be laid off. Under the old system, once these workers grew old their care was largely the burden of their enterprise. But as firms were already closing and others were downsizing or renegotiating their obligations, the new system saw local government take on the responsibility for social insurance funds. The problem, however, was that the local government social insurance funds did not at all correspond to the funds accumulated by the old workers who had been employed at state-owned enterprises. In order to guarantee that social insurance could be paid out at all, then, there was on choice but to use the portion of total funds sitting in new workers’ accounts, creating a deficit. In reality, the social insurance fees paid are mostly set by the scale of this historical debt. According to statistics gathered by Zheng Bingwen, in 2013 the deficit in pension accounts amounted to some 260 million yuan.[vi]

In line with the analysis above, however, this does not mean that young workers are funding the pensions of retired workers. The old workers’ pensions are what they themselves produced in their youth. In fact, those who were laid off from state-owned enterprises paid a huge price, and the pensions they receive in compensation are not nearly enough. The false appearance of old workers drawing funds from the young arises from the fact that, as state-owned enterprises were restructured, they also liquidated these old workers’ pensions—this only one portion of a much larger process of original accumulation, accruing cash for a handful of people.[vii] Calling this an “historical debt” is very accurate, then. But who exactly the “debtor” is in this situation is not entirely clear.

Photo Credit: Sina Weibo

Final Words

Why does the basic problem of the pension system described above reflect China’s rapid economic growth and its contradictions? Because the pension question directly involves all three elements of the triangular relationship essential to the Chinese economy: Labor, Capital and the State.

Firstly, the problem of the pension system covered above is one result of overaccumulation within the Chinese economy. In rational terms, accumulation should be for future consumption, with the increase in productive power today helping to create goods for consumption in the future. But in the terms of our actually existing society riven by class contradictions, it is not this simple. Instead, accumulation pushes aside consumption and assumes its place in order to solidify a system in which profit is pursued at the expense of an increase in living standards or services. Actually, in the era of the planned economy China also saw accumulation displace consumption, but this was because of an intentional strategy geared toward industrialization, with the goal of overcoming other industrial nations, and this strategy was rooted in the backwards conditions of the country itself. But under a socialist system, the reliance on rural surplus and workers’ consumption funds for accumulation ought to, at a certain point, be ultimately repaid. For example, society ought to use its formidable industrial capacity to produce low-cost agricultural machinery and everyday consumer goods.

But the reality of so-called repayment (反哺)[viii] is that it has a structural prerequisite: that the authority over society’s surplus be, for the most part, exercised through a communally managed economy—and it is essential that the masses of workers and peasants possess a certain control over this economy, to prevent their becoming alienated within it. By contrast, so long as the social surplus is mainly seized in the hands of private capital, it will always first and foremost be used to sate capital’s thirst for endless growth. It follows, then, that workers consumption must be sacrificed for the sake of profit and capital accumulation. According to the logic of capital, social insurance is, of course, not profitable. It is nothing more than a cost and burden. So we again return to the question of social insurance funds. We can conclude that, in order to both reduce private industry’s feeling of burden and more or less ensure a sustainable flow of funds for social insurance, the only method we can ultimately think of is to invest social insurance funds into state-owned enterprises. It can clearly be seen that so-called “repayment” still largely requires relying on the publicly-owned economy. But when all is said and done, to what degree to should you extend such an approach, in practice? This immediately becomes a question of the extent to which the economy takes on a communal character, and the degree to which control is given over to the workers and peasants.

In addition, via our analysis of the pension question we can also see that China’s rapid economic growth (over-accumulation) rests on a multitude of informal systems. Private industry’s large-scale and ubiquitous methods of accumulation, whereby worker’s rights are sacrificed for the sake of profit and they are left to wander on the edge of legality, also accumulates a symmetrical mass of contradictions as private industry levels more and more demands on the process of formalizing these informal systems. In recent years, we can clearly see an intensification of the conflict between labor and capital, and at the same time observe an escalation in the demands made in the ceaseless collective actions engaged in by workers (having moved from demanding their salaries or social insurance payments to demanding an increase in their wages and even the formation of labor unions).[ix] These efforts toward formalization will, to the same extent, smash existing benefit structures, and are therefore bound to be faced with enormous resistance. This contest will determine the direction of Chinese industry’s employment system and its level of workers’ rights in the future.

老板们在抱怨什么:养老保险拖累了企业发展吗?

作者: 江下的老马

日期: 2019年1月17日

土逗公社

“又要马儿跑,又要马儿不养老。”

编按:中国的社保问题似乎进入了一个两难的局面:一方面企业家们抱怨居高不下的社保缴费率加重企业负担,另一方面以养老金为代表的社保基金却多年入不敷出。其实,企业和政府对当前养老金的亏空都负有不可规避的责任,正是大部分企业实际上未足额缴纳社保、国企改制时遗留下工人养老欠账的问题加剧了当前的养老金危机;从某种程度上说,亏空的养老金成了中国经济高速增长的牺牲品。

2月19日,国家发改委等18部门发布《加大力度推动社会领域公共服务补短板强弱项提质量 促进形成强大国内市场的行动方案》(以下简称“《行动方案》”)。在养老方面,《行动方案》提出,全面放开养老服务市场。推动民办养老机构发展,取消养老机构设立许可,支持境内外资本投资举办养老机构,落实同等优惠政策。深化非营利性养老机构登记制度改革,允许养老机构依法依规设立多个服务网点,实现规模化、连锁化、品牌化运营。鼓励民间资本对企业厂房、商业设施及其他可利用的社会资源进行整合和改造后用于养老服务。开展城企协同推进养老服务发展行动计划。

也就是说,在今后的日子里,养老不能靠政府,还是要靠市场,最终,就是靠钱。

在整个《行动方案》中,我们甚至看不到社保发挥的作用,社保基金多年的入不敷出,似乎终于找到了“解决途径”。曾经,国企把职工养老作为包袱甩给了社会,有了社保;如今,民企对社保也喋喋不休,想把这个包袱继续甩给市场。其实,企业和政府对当前养老金的亏空都负有不可规避的责任,正是大部分企业实际上未足额缴纳社保、国企改制时遗留下工人养老欠账的问题加剧了当前的养老金危机;从某种程度上说,亏空的养老金成了中国经济高速增长的牺牲品。

今后,养老真真成了市场化运作了。这不禁让未富先老的我们感到一层层的焦虑,我们不敢想象我们老了以后会怎么样,甚至,我们都不知道能不能活到老的那一天呢!这个尴尬的养老局面,到底是怎么形成的?本文为你分析。

老板们在抱怨什么:养老保险拖累了企业发展吗?

2018年底,中国经济最令人瞩目的是两件事情:一件是所谓的中美贸易战,表明以美国为核心的全球分工体系或许正在发生某种结构性的演变,现存世界体系下各国的利益冲突越来越明朗化,这是中国经济所面临的外部压力;另一件是国内民营企业家抱怨经济不景气、经营成本太高而集体“罢工”,老板们不愿再投资导致国内固定资本投资萎缩,这是中国经济所面临的内部矛盾。

不过此“罢工”与彼罢工不同,得到了国家的积极回应,11月份召开的民营企业家座谈会提出“民营企业家是自己人”,随后就有一系列惠及“自己人”的优惠政策陆续出台,帮助民营企业接盘。那么老板们在抱怨什么呢?其实民营企业的成本和负担无非来自两个方面,一方面跟国家相关,主要有供应原材料的国有企业、帮助融资的国有银行等金融机构,还有政府税收;另一方面则跟劳动者相关,主要是工资和社保。本文将讨论的是企业社保负担的问题。通过对这个问题的解析,我们认为可以在一定程度上反映出中国经济在过去几十年发展过程中的特点以及其中蕴含的深层次矛盾。

一个表面上的矛盾

从表面上,中国社保基金存在一个非常矛盾的现象:一方面,中国的社保缴费率(社保费占工资的比值)号称处于世界最高水平,另一方面全国社保基金却又存在收不抵支的风险。也就是说,钱交得很多却不够用。

我国社保缴费率有多高呢?我们主要以社保基金中占比最大的基本养老金为例,基本养老金收支规模占到五项社保基金的70%左右;而在基本养老金中,又以城镇职工基本养老金占比最大(收支规模占比90%以上)。从缴费率看,城镇职工基本养老金的缴费率也就是养老金与工资总额的比值为28%,其中20%由企业负担,8%由职工负担。根据社保问题专家郑秉文的介绍:

“中国社会保险费率居高不下,其中养老保险费率既高于欧盟国家22.5%的平均水平,也高于OECD成员国19.6%的平均水平,甚至是美国和加拿大的2倍多,是韩国的3倍多 。从企业雇主的缴费来看,中国20%的费率是法国的2倍,美国、日本的3倍,加拿大、瑞士和韩国的4倍,企业的负担远高于这些国家……”

——郑秉文:《供给侧:降费对社会保险结构性改革的意义》,2016

按常理来说,养老保险交得越多应该越够用,可是从全国总量上看,从2015年开始,在扣除各级财政补贴收入之后全国城镇职工基本养老保险事实上处于收不抵支的状态。这是一个什么概念呢?首先要说到我国现行养老金在实际操作上是现收现付的模式,也就是说,我们现在交的养老保险费不是用来未来养我们的,而是已经用来赡养现在的退休老人。那么在这样的模式下,收不抵支就意味着即使“预支”我们这一代人的养老金给现在养老还是不够——想想就头大!(至于为什么会不够,后面讨论过度积累和历史欠账问题时将谈到)。

更悲催的是,辽宁等劳动力流出省份(往往也是落后省份)养老金账户亏空更加严重。这是由于社会保险基金并没有实现全国统筹,在多数地区统筹水平甚至仅停留在县级。举个例子,老张是一个从河北到北京打工的农民工,企业给他缴纳的基本养老金进入了北京的统筹账户(社保账户分为统筹账户和个人账户,统筹账户是大头),到他老了干不动要回老家的时候,这部分养老金却不会跟着他回到河北,而是留在了北京。在基本养老金全国总量已经需要财政补贴维系的情况下,这就进一步加剧了劳动力流出省的困难,相当于落后省份不仅给发达省份贡献了劳动力,还补贴了养老金。如下图所示,2016年在31个纳入统计的省、市、自治区中,已经有7个地区的城镇职工基本养老金处于亏损状态,尤其以辽宁和黑龙江两省最为严重。

社保缴费率高代表民营企业的负担重吗?

许多企业家抱怨社保费率高推高了企业成本,在去年年中政府提出社保费从2019年开始由更加严格的税务局收缴时,有些老板更是担心足额缴纳社保会把企业交垮(emmm也就是说他们从来没有足额缴纳过……)。那么社保缴费率高代表民营企业的负担重吗?表面上看是如此,但我们认为至少能从以下两方面反驳:

第一,名义上社保费占工资比例高可能是因为老板开的工资太低了。社保缴费率是一个相对值,是社保费用除以工资,所以说社保缴费率高既可能是因为社保费用的绝对水平确实很高,也可能只是因为工资的绝对水平很低。在媒体的宣传中,后面这个因素是很少被提及的;但众所周知的是,中国工人一直以来都是廉价劳动力的代名词。

第二,中国实际的社保缴费率并没有名义数字显示得那样高,大部分企业并没有合法足额地缴纳社保。首先,我们必须考虑到占中国劳动力三分之一以上的农民工群体并不能被全国社保基金有效地覆盖。根据农民工监测报告,2014年农民工参加养老保险的比例不过16.7%,此后的数据不再公布,但想必也不会很高。农民工的社会保障难以受到劳动法、劳动合同法、社会保险法的保护,很大程度上依然如马克思所说的,“要在以往或随着资本的出现正在消逝的生产方式中寻求拐杖”。

其次,在城镇职工社会保险的缴纳中也存在普遍的瞒报、低报工资、不足额缴纳的情况。媒体中经常引用的数字是,中国企业中足额缴纳社保的比例不足30%。所以当2019年社保费用由各地税务局统一征缴的消息放出之后,社保费率高的问题才又被拿出来反复说事,很多老板担心瞒不过税务局,真的要严格足额缴费了。一般认为,税务局由于征缴个税的原因对企业职工的实际工资水平更清楚,执行力更强,因此将严重缩减企业躲避足额缴纳社保的空间。社保足额缴纳的执行对竞争力弱的中小企业有很大的影响,仅社保补缴一项就可能使不少企业陷入亏损。

可见民营企业所谓的社保高负担其实已经在相当大的程度上转嫁给了工人,企业家们抱怨社保费率高推高企业成本在很大程度上是一个伪命题——毕竟,你不能抱怨没有实际发生的事。上述事实说明中国大量中小企业的经营长期依赖一种非正规的用工体制,在这种体制下劳动者的权益无法得到合法的、完全的保障。正规制度格调通常很高,“切实保障劳动者权益”是其底线;而对于靠压榨廉价劳工来积累资本的大量企业家们来说,漠视劳动法、劳动合同法的情况见怪不怪,“切实保障劳动者权益”说是够不着的地平线还差不多。

于是,非正规制度取代正规制度在中国成为了普遍的现象。在生产关系的等级结构中,以农民工为代表的非正规劳工处于最底层。他们是社会财富主要的创造者,却也是增长代价主要的承担者。甚至,他们的处境可能还比不上自然环境。经济增长过程中对自然环境的破坏由于威胁到社会中所有阶级的生活环境,实际上要更容易得到主流话语的关注,比如北京的雾霾问题;而劳工的基本权利则经常湮没在自由市场经济的遁词之中,难以激起人们同等程度的共情与愤慨。

社保亏空只是因为人口老龄化?

媒体经常将社保基金尤其是基本养老基金的亏空归咎于人口结构的老龄化,在现收现付养老模式的框架下看确实会得到这样的推论。随着人口老龄化,每个劳动人口要负担的退休人员就会增加,养老金收支平衡的压力就会越来越大。

但如果跳出现收现付的框架来看养老问题呢?现收现付不过是操作的模式,须知促成事物的直接原因并不等于根本原因,人口老龄化不过是压死骆驼的最后一根稻草。从根本来源上看,退休之后的工人所拿到的养老金都是他或她年轻时创造的价值的一部分,并不是其他阶级的恩赐。社会养老金本来就是社会总剩余产品的一项必要的扣除,或者视为劳动力价值的一部分也并无不当。作为劳动的回报,养老金理应足额给付;如果一个社会的养老金发生不足,实际上就表示原来的养老金被挪作他用了。更直白地说,就是这个社会剥削率太高,把养老金都剥削走了——那它被剥削去了哪里?对于一个连续保持高速增长的经济而言,剩余产品的主要用途就是积累,也就是说养老金被资本家挪作再投资的资金了。可见,所谓养老金不足的问题本质上是积累基金挤占社保基金,是一个由过度积累导致的问题。

在这个前提下再来看人口老龄化在其中所起的作用就比较清楚了。人口老龄化的负担是与“人口红利”相对的,不能只让几亿工人贡献廉价劳动力而不给他们养老。当几亿中国工人尚属年轻的时候,这个数量庞大的产业后备军使得他们的工资和社保基金被压到了一个很低的水平。这就形成了大规模的剩余价值,既输送给国内的资本,也输送给国际的资本;既形成经济高速增长的基础,也成为剧烈贫富分化的源头——这就是所谓的“人口红利”。而当这几亿工人阶级年老,亦或遭遇工伤和疾病的时候,高速增长的经济却没有足够的社保基金对他们进行保障。他们只是新自由主义时代的一波韭菜,在被割去了青春之后,剩下的部分是要烂在土里的。

社保的历史欠账

最后还要说明造成当前社保基金不足的另一大原因,也就是历史欠账问题。中国现行社保制度虽然明面上是社会统筹与个人账户相结合,实际上依然是现收现付制,个人账户(为自己未来养老做积累)积累的资金基本上已挪用于统筹支出,形成空账(账面上有那么多钱,其实没有)。为什么个人账户里的资金要被挪出来?这实际上是由世纪之交的国企改制引起的。国企改制造成超过2000万人下岗,这部分工人的养老在旧体制下本该由企业主要负担;但企业已经被改掉了,于是就在新的社保体制下由地方政府的社保基金负担。问题是在这个新体制中,社保基金并不存在对应国企老工人的社保基金积累。为保证社保基金支出,就不得不动用新工人的个人账户部分,于是形成后者个人账户的空账。事实上,养老金缴费率主要就是考虑到历史欠账的规模而制定的。根据统计数字,2013年我国养老金个人账户空账大概为2.6万亿元(数据引自郑秉文:《中国养老改革之我见》)。

与之前的分析一样的道理,我们并不能就此认为这是新工人在养老工人。老工人的养老金是他们年轻时创造的。事实上,国企下岗工人付出了巨大的代价,这部分养老金的补偿是远远不够的。造成这种假象的原因在于老工人的养老金积累随着国企改制一起被改掉了,事实上形成了一小部分人原始积累的来源之一。所以用“历史欠账”来指称这个问题是很恰当的,只不过债务人究竟是谁,是不太说得清楚的。

尾论

为什么我们说基本养老金的问题可以反映中国经济增长的特点以及其中蕴含的矛盾呢?因为养老金问题直接涉及到了中国经济中最重要的三角关系:劳工、资本和国家。

首先,我们说养老金问题是中国经济过度积累的后果之一。按道理,积累是为了将来更多的消费,现在提高生产能力是为了以后生产更多消费品。但对一个存在阶级矛盾的社会而言却不是这样简单,积累挤占消费的现象会固化为一种制度,为追逐利润而非提高生活水平而服务。事实上在计划经济年代,出于工业化赶超战略的考虑,中国就存在积累基金挤占消费基金的情况,这是由落后国家的国情决定的。但是在社会主义体制下,工业积累对农业剩余和工人消费基金的挤占在到达一定时期之后就应该开始反哺,比如利用更强大的工业生产能力提供更廉价的农业机械、生活用品等。

但所谓反哺的实现是有制度前提的,即社会剩余的支配权应该很大程度上掌握在公有经济手中,并且工农群众需要对公有经济具备一定的掌控力以防止其发生异化。相反,如果社会剩余主要掌握在私有资本手中,它就首先要满足资本不断增殖的渴望,就必须为了利润和资本积累牺牲工人消费。对资本而言,社保当然不是一种福利,而是成本和负担。再回到社会基金的问题,我们发现如果既要给民营企业减负,又要至少保证社保基金的收支可持续,最后能想到的办法就是社保基金入股国有企业。可见,所谓“反哺”很大程度上还是要依赖公有经济的。但是这种作用在实践中究竟能达到什么程度,就是另外一个直接关乎公有制经济性质、工农群众对其掌控程度的问题了。

其次,透过养老金问题我们也能看到,中国的高速增长(过度积累)是以很多非正规制度为基础的。企业大规模地普遍性地牺牲劳动者合法权益来获取利润,游走在法律边缘,这种依赖非正规制度的积累体制会积攒相当多的矛盾,进而越来越表现出对正规化制度的诉求。我们从近年来劳资冲突的紧张化,以及集体行动中工人不断升级的利益诉求(从讨薪、补缴社保到涨工资,再到组建工会)中可见一斑。这些正规化的努力会在相当大的程度上打破既有的利益格局,因此必定都会面临极大的阻力;而不同主体的力量博弈将会决定中国企业用工制度、劳动者权益保障水平的未来走向。

作者:江下的老马

编辑:土逗饼

美编:太子豹

Translators’ Notes

[i] For more detail on the legal requirements, see Adam Livermore, “Understanding China’s Pension System,” China Briefing, 14 September 2010. <https://www.china-briefing.com/news/chinas-social-security-system/>

[ii] As part of the latest round of the crackdown on leftist and labor activist groups since 2015, Tootopia was shut down and forced to delete its online archives in June 2019. This article was widely reposted and can now be accessed here, for example: http://www.wyzxwk.com/Article/shehui/2019/01/398397.html

[iii] 郑秉文:《供给侧:降费对社会保险结构性改革的意义》,2016

[iv] This refers to the name of a series of reports released by the National Bureau of Statistics. The report used here by the author is not directly cited, but the 16.7% figure appears to originate in their 2014 report, available here: <http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/201504/t20150429_797821.html>

[v] This is from the Grundrisse, the text used is the Martin Nicolaus translation, and the quote is located in “Notebook VI – The Chapter on Capital,” available online here: <https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1857/grundrisse/ch12.htm>

[vi] The author cites an article titled My Perspective on China’s Social Insurance Reform by Zheng Bingwen: 郑秉文:《中国养老改革之我见》

[vii] The author is arguing here that the restructuring of socialist-era industry was an act of “original accumulation” in the Marxist sense, in which land, resources and/or labor are seized by a powerful minority, to be thrown into capitalist production. Original accumulation is also defined by the fact that it establishes and maintains the conditions for continuing capitalist accumulation. Often mis-translated as “primitive accumulation,” this is sometimes seen as the historical moment initiating capitalist production in an area. Though original accumulation does mark the entry of capitalism into a particular territory, it is incorrect to perceive it as a delimited “stage” that is then simply replaced by formal, less directly coercive mechanisms of exploitation and plunder. Instead, it is more accurate to think of original accumulation as changing form over time, but existing alongside more formal capitalist relations of production. It is both the continual maintenance of the baseline conditions for accumulation, and the mechanism whereby capitalism undergoes geographic expansion. We concur with the author here that the deindustrialization of the socialist era industrial belt was a key example of early original accumulation in China. For more detail, see part two of our economic history: “Red Dust,” Chuang, Issue 2, Bell & Bain, 2019.

[viii] Here and in several other places, the author is using terms common to the Chinese New Left, which combine a nostalgia for socialist era history (i.e., referring to “workers and peasants” in the subsequent sentence) with moral appeals that draw from socialist history and Chinese moral philosophy in equal parts. The term used in this instance, 反哺 (fanbu), commonly invoked by the New Left, derives from the 6th-century writings of Emperor Wu of Liang, describing a raven that provides food to its mother after becoming an adult. In the contemporary usage, the meaning is basically a generic one of fulfilling the duties of filial piety by taking care of your parents, or the elders of society at large.

[ix] The author takes a position common to many leftist activists and academics both within and outside China, claiming the existence of a “workers movement” that is in the process of moving to more aggressive demands, including demands for the formation of independent labor unions. As we have covered extensively elsewhere, this is a mis-portrayal of both the recent history of unrest in China (see: “No Way Forward, No Way Back: China in the Era of Riots,” Chuang, Issue 1, 2016) as well as the current trends exhibited by the best available records of mass incidents (see: “Picking Quarrels: Lu Yuyu, Li Tingyu and the Changing Cadence of Class Conflict in China,” Chuang, Issue 2, 2019).