In recent years, right-wing discourse has become more and more common on the Chinese internet, particularly among young people. There seems to be a general perception among left-leaning activists (but particularly students, who tend to be involved in more discursive debates) that the right-wing politicization of young people is now far outstripping that of the left. Though this is for the most part an online phenomenon, the more mainstream acceptance of right-wing cultural interventions is something to be wary of. There are also certain events that hint at how the New Right might take material shape in the future: for instance, young nationalist youth volunteering to go “fight the traitors” in Hong Kong. Though the struggle in Hong Kong has a complex and unique character, we suspect that similar sentiments could be mobilized in other, hypothetical, instances of severe civil unrest in the future. However, in order to deflate the oft-invoked specter of a hyper-authoritarian China, we have to emphasize here that online comment boards do not compose a real right-wing mass movement. At present, the Chinese state has little need for the mass mobilization of a militaristic far-right. But the slow gestation and popularization of right-wing thought is nonetheless worth deep examination.

The following article was originally posted on Tootopia (土豆公社) in February of 2019.1 We’ve chosen to translate it for a few reasons: First, it acts as a good representation of the types of cultural commentary circulating among young Chinese leftists. We can thereby see how such an audience regards the ideological mechanisms that lie behind cultural production, and how social commentary is voiced in response to such mechanisms. Second, it offers a good critique of two major trends in the contemporary Chinese political scene, at least as they manifest online. Though some of those who hold similar positions might consider themselves “on the left” in some fashion, we define such positions as within the Chinese New Right. In line with this, the author dissects these two right-wing trends of thought, illustrating yet again how variants of nationalism, often alloyed with a fetishization of industrial development, act as a sort of a priori presumption within the Chinese political scene. The article itself stands out precisely because of its emphasis on internationalism—although the author still seems to counterpose a “true patriotism” against the more reactionary forms of nationalism detailed here.

The two trends singled out by the article are translated here as “Prometheans” and “Young Cyber-Nationalists.” But it should be noted that no adequate, exact translations exist for the original terms. Translated more literally, they are the “Industrial Party” (工业党) and “Little Pinks” (小粉红), respectively. The author gives a more specific definition of each, emphasizing the basic demographic and class background of the two trends’ supporters. But some basic knowledge of each term is presumed, so it will help to give a brief overview to orient the reader: The “Industrial Party” is often used interchangeably with the “Party of Technology” (技术党), and both are terms that refer to those who believe that the advancement of technology via industrial development is the most essential element behind human progress and drives ideological changes. Though this seems to express a basic Marxist position, the emphasis is placed on technology itself, rather than the reorganization of the relations of production. It is usually (though not always) expressed as a form of technological reductionism, then, and carries similar connotations as Promethianism in English, which bears a symmetrical ambiguity (i.e. it’s possible to interpret it as a form of reductionism, but it’s also possible to cast it in a more charitable light). The term “Little Pinks,” by contrast, has less breadth. It refers to netizens who patriotically defend China online—both on the domestic and overseas Chinese internet. They are on average very young, and at this point have very little presence offline. In this regard, they are maybe comparable to the early years of the alt-right in the US, though without any attempt to incorporate “countercultural” elements into their nationalism. We translate it as “Young Cyber-Nationalists,” emphasizing the meaning but losing the simultaneously diminutive and illustrative phrasing of the original.

The entry-point for the author’s critique of these trends is not, however, overtly political. Instead, each is explored through their cultural presence, with the author arguing that both trends converge in their defense of the popular sci-fi film The Wandering Earth. In recent years, the international renown of Chinese science fiction has grown rapidly, after being catapulted to prominence by well-received translations of Liu Cixin’s Three Body Trilogy. Now a series of major films and possible television series are in the works, largely based on Liu’s writing. Meanwhile, lesser-known Chinese sci-fi authors have begun to make a name for themselves in English, largely due to the translation work of American-born-Chinese author and translator Ken Liu. The range of Chinese sci-fi on offer in English has broadened substantially, and it’s not an exaggeration to say that the genre is now one of the most popular forms of Chinese cultural production consumed by foreigners. This has also inflated its importance for the Chinese state, which is intentionally building “soft power” via the promotion of domestic cultural products overseas. Though Liu’s books have already reached widespread popularity, the real key to this effort is a series of Chinese-produced films capable of challenging Hollywood-style blockbusters. The film version of Liu Cixin’s short story, The Wandering Earth, is one of the first major films released in this effort. A fully domestic production, the movie performed well despite departing substantially from the source material. It is currently China’s second-highest grossing film of all time, as well as the second-highest grossing non-English film of all time (behind 战狼2 – Wolf Warrior 2, another Chinese production with strong nationalist undertones), and has made it into the top 20 highest-grossing sci-fi films of all time.

Like any major cultural production, it reflects the contradictions underlying the “common sense” ideology of the society that produced it. This is the entry point for the author, who sees the film as a looking glass capable of showing the conservative core of the film’s political presumptions. The original title, difficult to translate literally, refers to the zhaoyaojing (照妖镜), a magical mirror referenced in ancient Chinese literature that reveals ghosts and demons in its reflection. A related folk superstition led to the practice of hanging circular mirrors, referred to as zhaoyaojing, above main entryways of a new house. The author’s original title might then be translated as something like: Wandering Earth: A Magic Mirror Reflecting the Monstrosity of the Prometheans and Young Cyber-Nationalists. The idea is, essentially, that the conservative nucleus of these trends of thought is revealed in the film’s mirroring of these ideological assumptions, and especially in the fan response to the film’s reception. Though we don’t endorse all the positions taken by the author, the piece is a rare intervention against the kind of default nationalism assumed by many activists and political theorists (“left” and right) in China.

–Chuang

Introduction by Tootopia Editors

Wu Jing, idol of the young cyber-nationalists, and Liu Cixin, spiritual leader of the Prometheans, have come together to create the film Wandering Earth. It’s only natural that these two groups, happily joined together, couldn’t stand to see the Douban hipsters deflate the film’s average rating.2 But in the background of this great spat, the powers of contemporary China’s three major tides of thought collide.

The Wandering Earth: A Reflection of the Chinese Right

By Yuyan

Originally posted on Tootopia, 13 February 2019

As in previous years, the lineup at movie theaters during the Spring Festival is divided up between domestic productions. But this year, one stands out: the controversial and popular film, The Wandering Earth. Aside from the extremely flattering media and the inevitable disappointment that accompanies the film’s departure from its eponymous source, the controversy has largely arisen from two entertainment figures who, when they make public appearances, project an aura that attracts die-hard fans: Wu Jing, the protagonist, and Liu Cixin, the story’s author. And these two individuals thereby represent two major trends in contemporary Chinese society

Spokespeople of the Young Cyber-Nationalists and Prometheans

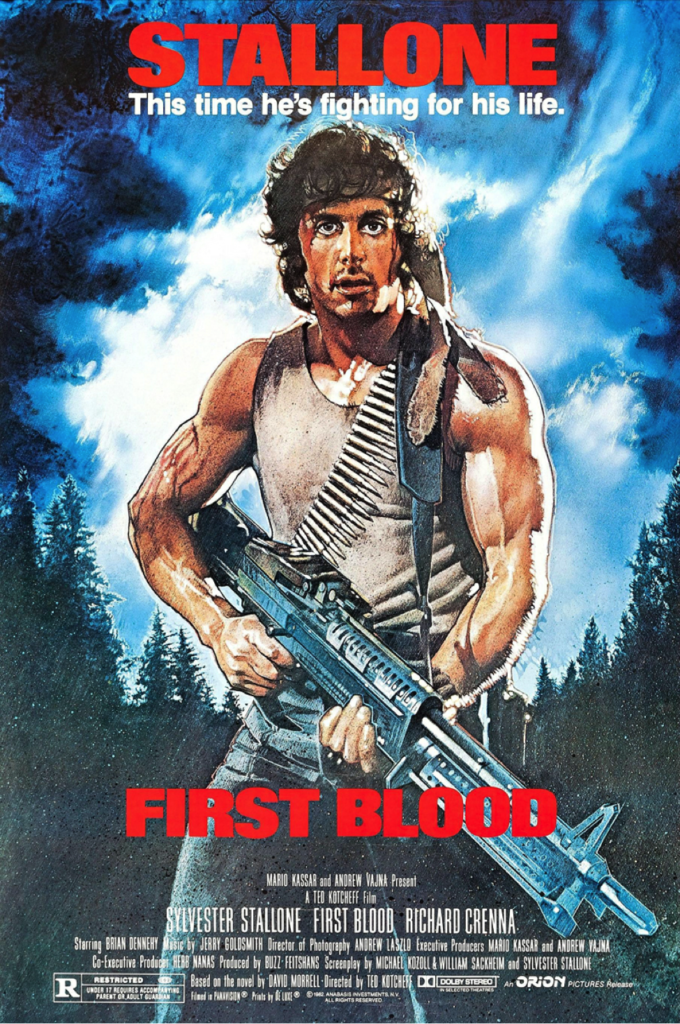

Wu Jing has today become a symbolic representative for the ideas of the young cyber-nationalists, similar to what happened to Sylvester Stallone after First Blood, where he played an American soldier in Vietnam. The young cyber-nationalists are 20-somethings with a relatively low level of education, sitting somewhere in the lower rungs of the urban middle class. They believe that hostile forces from overseas are either the root of all evil in Chinese society, or at least are the main obstacles to be overcome, and they therefore think highly of China’s rapid rise in military power and its hard diplomacy.

Liu Cixin has become the spokesperson of the Promethean trend, which is based among people in their thirties and forties who tend to have a higher level of education and compose the upper rungs of the urban middle class. They hope that China’s industrial level can quickly surpass that of the West, and they revere the idea of a small intellectual elite ruling a country. But they also often fear that the vast uneducated masses might decide to rise up and lay siege to the efficient order of the elites. It is, then, very easy for them to take pleasure in the fictional scenes of extreme cruelty in Liu Cixin’s writing, because, in their opinion, such scenes of cruelty are simply a reflection of the dog-eat-dog reality of the world (domestically and internationally). This leads to the conclusion that the small intellectual elite must become strong leaders, since the masses cannot rule themselves and therefore must be protected by the intellectual elite while also following their orders, which are pronounced in the name of science.

The hope and imagination of Chinese Science Fiction gathers these two groups together under a single banner. On the one hand, the young cyber-nationalists consider Chinese-made Hollywood-style blockbusters to be a symbol of cultural soft power. On the other, the Prometheans take Chinese sci-fi movies to be a symbol of China’s technological hard power. Therefore, although the film has almost completely transformed the plot of the original novel, especially insofar as it changed the portrayal of the masses from ignorant and backward to wise and courageous, both sides have nonetheless found a powerful resonance in their unyielding support for such domestic sci-fi films. Ultimately, both sides are volunteer propagandists for the state (ziganwu),3 deeply driven by the emotive power of narrow nationalism and a spirit of exceptionalism. The Prometheans are simply a more rational and refined version of the young cyber-nationalists, while the young cyber-nationalists are young, precocious versions of the Prometheans, and as they age they will become Prometheans themselves.

After the premiere of The Wandering Earth (now China’s so-called number one domestically produced hard sci-fi film), these keyboard warriors not only found a shared idol, but, more important, they unexpectedly discovered a shared enemy. During the Spring Festival most people have substantial free time, and therefore a severe conflict was ignited online over the weeklong break, each faction intensifying its crusade against the other, such that the die-hard fans of the movie devolved into unilateral condemnation of their opponents. The narrow nationalism and xenophobia of the young cyber-nationalists combined with the positivist zealotry and rationalist prejudice of the Prometheans to form a sort of fascist-style fanaticism within online discourse. Together, they sought to suppress any voice that questioned the film or was at all critical of it, howling, without a shred of irony: We must uphold The Wandering Earth! If you don’t give it a good review, you are not Chinese! If you don’t give it a good review, you are not a patriot!

Do We Want Wealth and Technology, or Science and Democracy?

On the other side of the controversy lie those who gave a low rating to The Wandering Earth online, including all of those who criticized the film from various angles: whether this be their own personal experience of watching it, critiques of the cinematic skill behind the film or the narrative sequence, or conceptual critiques like the portrayal of women, individual power, freedom of speech or the transparency of public discourse. Faced with the fanatic assault of the young cyber-nationalists and the Prometheans, such disparate groups gradually started to cling together for protection, eventually forming a united front. They did not concede to the opinion of many professional film-reviewers and kindhearted audience members, who argued that “a blemish does not obscure jade’s luster.” Instead, they persisted in assigning the film a low ranking.

If this conflict has already far exceeded the box office success of the film itself, this is because it reflects a central contradiction that will arise in struggles over the direction of the development of Chinese society over the next decade: Do we want wealth and technology, or do we want science and democracy? In other words, do we want something like the desperate fighting against the tide represented by the Self-Strengthening Movement of Li Hongzhang and Zeng Guofan, or do we want something more like the New Culture Movement of Chen Duxiu and Hu Shi, starting over from scratch?4 For now, this question has not clearly pressed through to the surface. Instead, we can focus on The Wandering Earth and the explosive debate within public discourse that has accompanied it, as well as the social trends that sit behind this debate.

To be fair, although The Wandering Earth is full of scenes featuring over-idealized characters with exaggerated heroism, not to mention the film’s general anti-democratic and anti-scientific feudal values (for instance, the extremely conservative obsession with one’s native soil: “Earth has oppressed me thousands of times, but I am nonetheless attached to it”), some of its content is still able to instigate a feeling of awe in the audience. For example, people from all over the world coming together in the rescue mission, the two astronauts sacrificing their lives for the benefit of all humanity, the world deciding by lot which half of the population will take refuge in the underground cities and which half must accept death. These aspects are strong manifestations of modern values like liberty, equality and fraternity, which are themselves an incarnation of the heritage of socialism, embedded in the subconscious of Chinese people.

Unfortunately, these aspects that accord with socialist values are merely occasional decorations, or simply asides, separate from the main act. All the governments and peoples of the world forgetting their old differences and working together, what a moving scene! But what of the United Earth Government? And what of these people from all over the world? These topics, though deserving of detailed exposition or at the very least some attention, are not even openly addressed in the film. The United Earth Government merely toys with the protagonist, leading him in circles, and the people from all over the world are confronted by a series of setbacks which lead them to give up one by one until, hearing the crying plea of the female lead in a global broadcast, they immediately leap up passionately and return to the struggle. From start to finish, the film’s main focus is on a handful of heroes determining the fate of the world. The main recurring scene is merely an illustration of the deep feelings between father and son, placing a halo on the protagonist. Such scenes also contain an implicit system of values: a mixture of the bewitching potion of feudal patriarchy and the self-help “chicken soup for the soul” of bourgeois individualism.5 Both are little more than stubborn relics that obstruct modern development and social progress. The choices made about such scenes are not merely based on what is interesting or not, but, in the end, reflect the values of the screenwriter and director. The internationalist value system stressing the collective fate of humanity is little more than a stopover within this vacuous fantasy. Aside from the saintly, omnipotent protagonist, the film offers no realistic or logical means to obtain this lofty dream. Instead, it has difficulty even concealing the myriad power struggles and egocentric schemes that motivate its characters.

Therefore, the film is really more of a Wuxia story disguised as sci-fi. The only difference between the film and a classic Wuxia story in the style of Jin Yong is simply that the fantasy figure of a heroic, knight-errant protagonist serving the broad masses is built up until he is actually saving all of humanity. Moreover, despite being enveloped in the appearance of sci-fi, the core element of sci-fi has been entirely excised: exploration of the relationship between science and human society. The film doesn’t reveal any ideas about the future of society or humankind, merely fabricating an End Times disaster for the characters to face. And this particular disaster is actually an expression of real disasters: capitalist economic crisis, environmental crisis, and crises of political legitimacy, as well as protests against them. It follows that the fantasy of a heroic savior, as well as the fantasy of all the people of the world, undivided by class or race, coming together to rescue themselves, ultimately become the sigh of the oppressed, the heart of a heartless world, as if they were the spirit of the spiritless capitalist system.

Behind The Wandering Earth, the Underestimated IQ of the Audience

Netizens satirically hit the nail on the head with their criticisms, arguing that The Wandering Earth is not hard sci-fi but instead “trying-hard-to-be sci-fi,” or that it’s just got a “hard packaging of sci-fi” and has been “pressed hard to fit into the slot of sci-fi,” and that its title should be changed to The Clickbait Earth.6 In a word: an embroidered pillow is still a bag of fluff. In everything from the main themes (rebellious heroism, familial affection, the coming-of-age process), to the narrative flow (following multiple groups of characters, having the leads give speeches, including an elder and a pretty girl, showing the family photograph, valuing human life, displaying virtues of fraternity, having unexpected mishaps arise, a major climax and a satisfactory ending), and the production methods (zooming camera shots, visual effects, impressive backdrops and symbols of consumption)—all are completely copied from the style of Hollywood’s film industry. The Wandering Earth totally ignores the soul of cinematic art: telling a story.

Almost every scene simply serves as a foil for the heroic lead characters, giving an excuse to display exaggerated family values and nativist sentiments, as well as space for the deployment of Hollywood-style techniques. It is only from this perspective that the many weird and abrupt features of the film’s narrative make sense. For example: the spooky voices of the unseen United Earth Government, the AI system MOSS being rendered idiotic and taken over by the heroic lead character, the female character (called “Duoduo” or “Yatou”) who always holds back the heroic lead, the heroic astronaut’s wife who is willing to sacrifice herself yet barely shows her face (to say nothing of playing up her noble spirit), or the astronaut’s mother-in-law who is remembered only in her service to a man (cooking a bowl of noodles for him)…. Or for another example, why didn’t they edit out pointless subplots like when Duoduo’s failure to keep a secret caused a minor hero to be caught up in a car chase? These decisions were made not merely to match the Hollywood clichés, as if any big blockbuster required a car chase. The more important reason the director makes these plot choices is to play tricks on the audience: when you’re crying you can’t pay attention to whether or not the plot is rational, so they do the utmost to stir up large emotions or send a side character to their death. They make you laugh in order to hinder you from going online and making malicious comments, not caring whether or not you understand the plot. Certainly, this is Hollywood’s public secret: the vast majority of audience members do not use rational thought, instead merely giving a conditioned reflex in response to suggested moods, like lower-order organisms.

The Kernel of Reverse-Nationalism

In reality, if we’re speaking of the “hard core,” the true core of the film and the thing which unifies its supporters is a bone-deep kernel of reverse-nationalism, so customary that it’s rarely called into question, summed up in the thought: all things from the West are good and proper. Ironically, in the eyes of many audience members, the film would be imbued with their nativist sentiments only after being disseminated and packaged through the media, and therefore it became unacceptable to criticize their idol. Among the supporters of The Wandering Earth there are a few die-hard fans, but most are just kindhearted, down-to-earth people. Together, they criticize and jeer at those who think Hollywood sci-fi films are superior, calling these people “Admirers of Foreign Dogs.” But they don’t realize that they are the pot calling the kettle black, because the very reasons they support The Wandering Earth are founded on a standard of critique drawn from the Hollywood capitalist film industry. Furthermore, Liu Cixin’s novels and even contemporary Chinese sci-fi more broadly has gained popularity in the media and within academic circles, thereby entering into the view of the public. But this started when Liu Cixin’s The Three Body Problem won the English-speaking world’s Hugo Award for science fiction, and a major reason for this was that the foreign translator, himself a writer and avid fan, used more lively and literary language in the translation than in the original. To use another example: after Mo Yan won the Nobel Prize for Literature, many WeChat feeds marketed articles falsely attributed to Mo Yan, in order to gain more traffic. This is yet another example reflecting the way in which reverse nationalist thinking is universal within our country.

But the knockoff Hollywood images, the story’s backdrop of a shared human destiny, and the many tear-jerking moments of continual sacrifice for the sake of saving the earth—all operate on the surface to cover up the many deficiencies of The Wandering Earth’s narrative and value system. Moreover, the dissemination of “the number 1 domestically-produced hard sci-fi, Hollywood-style blockbuster” has itself produced simple nativist sentiments in audiences, despite such deficiencies, making them unwilling to go critique the film. This sort of simple nativism and the familial sentiments repeatedly shown in scenes of the son, father and grandfather are actually identical in their content: the foundation beneath both is the particularistic system of ethics advocated by traditional Confucianism (“close relatives and distant relatives should be treated differently,” “relatives cover for each other,” social and biological determinism, etc.), rather than the universalist ethics advocated by modern society (“making the rules democratically in front of everyone,” “showing love for others equally,” “heroes do not pay attention to one’s origins”).7 It’s just like the popular online phrase says: “You can throw a thousand curses at your alma mater, but can’t bear it if others utter just one.” Against the backdrop of all of humanity rescuing itself, the ideology of the family nonetheless gives precedence to one’s own immediate progeny. From this, we can observe both the deficiency of imagination in the script and its adherence to traditional values, all in one place. Taking this sort of particularistic ethics to the extreme, it follows that die-hard fans of the film would express a narrow nationalist way of thinking in phrases such as “the other must be different from me,” or “those who wrong the Han will be punished no matter how far away they are.”8 What kind of work of art has these sorts of fans? We can truly say: “birds of a feather flock together.”

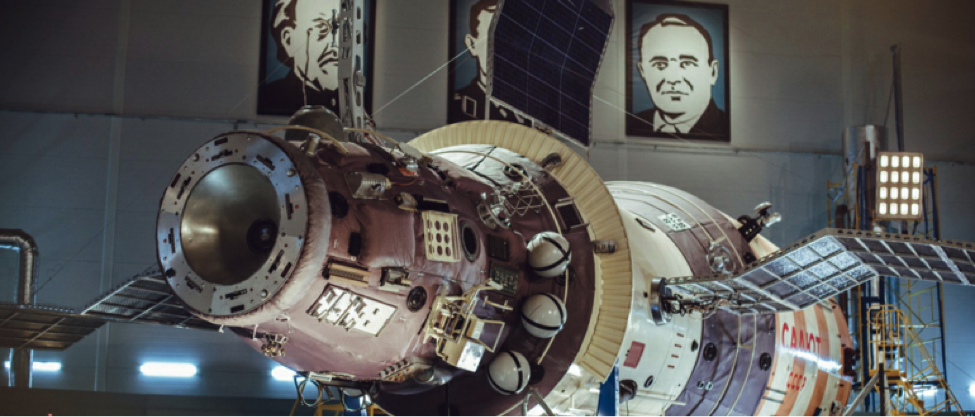

Without comparison there is no harm, although the lesson of history is that people never absorb the lessons of history. The Russians spent 40 million RMB on the production of Salyut 7, and compared to the 230 million RMB invested into The Wandering Earth, it’s hard to see the difference, yet the Douban audience score is only 7.7 (at the time the author finished writing The Wandering Earth had already seen its score on Douban slide from 8.5 to 7.9). Some professional critics (for example: Zhang Xiaobei, Wuya Huotang, Xiedu Dianying and Lu Zhiyu) were generous in giving The Wandering Earth 5-star reviews, showering it with praise and encouragement. Their main reason was that the visual effects had the appearance of a Hollywood film—but these same reviewers had only given the Russian film 3- or 4-stars. Another critic going by “Zhang Yongxuan Wayne@,” though praising the film Salyut-7 (“it uses low-cost techniques with great efficiency, reaching the same level of visual effects as Hollywood”), nonetheless only gave it a very low 2 stars. Meanwhile, he gave The Wandering Earth the standard of 3 stars, afterwards giving it the severe critique: “This is not China’s premiere hard sci-fi film. I just have to say nice things, but on a personal level I was disappointed that it did not meet my expectations, especially when it came to the fake-looking the visual effects, which simply didn’t meet the visual standards of sci-fi. Relying on the imaginative power of the novel, the execution was clearly weak. The development of the story and the attempt to implant deep feelings were both particularly garish. Moreover, the use of digital confetti action shots and big explosions to stir up emotion as well as the constant, narcissistic attempt to twist everything to fit a pedantic system of values were both hideous. I was embarrassed to death on several occasions.”9 These film industry insiders’ attitude is narrowly focused on protecting their baby and defending the industry’s common interests.

One user, calling himself “Fan of modern Chinese history” gave the film a low one-star, offering the reason: “Our nation has been harmed and humiliated by polar bears [i.e. Russians] for nearly two centuries, much longer than by the Japanese, and while the latter have expressed remorse, the polar bears think they haven’t done anything wrong… so I reject anything produced by them…. Of course this may not be entirely fair regarding films and the struggling masses, but… so the fuck what?” This narrow nativist sentiment is at last taken to its conclusion! We cannot help but ask, are Russians not also members of the great human family? If The Wandering Earth, as Chinese people’s botched copy of a Hollywood blockbuster, is worthy of encouragement, then are the Russians’ successful imitations not also worthy? Are we really saying that Chinese people can only encourage things Made in China, and cannot support things made even better in other countries?

What is a Good Chinese Movie?

Nonetheless, returning to the point, of course we can encourage domestic productions! As long as the artwork is actually excellent, there’s no problem. For example, the 1986 film, Dislocation, a genuine hard sci-fi film. Raising the issue of the relationship between robots and humans, the film could even be considered the first major milestone in domestically-produced sci-fi movies. And yet how many people have heard of it? I’m ashamed to say that it was only through the discourse around The Wandering Earth that I myself just heard of it. If you have no resources to find older films online, you can read the newly released, domestically produced short story The Realism of The Wandering Earth,10 and learn about the fundamental components and real charm of sci-fi stories—rather than following only those authors and critics who blindly chase after Western book prizes. It is a mistake to think that it is only those who win Western awards or conform to Western critical standards are producing excellent works of art.

Thinking back a little, in the course of Chinese filmmakers’ arduous struggle through the ‘50s to the ‘90s, a number of excellent works were produced. But none relied on large charity investments or ticket sales, and they didn’t cater to the nationalist tailing of Hollywood standards either. Instead, they relied on a sincere pursuit of social progress and human liberation. Even The Wandering Earth makes its audience feel fragments of such lofty ideas, with the heritage of socialist culture deeply engraved in it. But today, if we do not break free from the mechanisms of film production dominated by capital and power (权贵), trying in vain to rely on vested interests, then any efforts to effect a renaissance of Chinese film will be as doomed to failure as Sun Wukong trying to escape the Buddha’s Palm.11 The Wandering Earth is no more than another disappointing milestone on this wrongheaded path of the arts.

One of the Ancients said: “The good thing about The Water Margin is that they surrendered, so it can provide a negative lesson for the People: they can know who surrendered.”12 Another said: “The Water Margin is very clear: Since they did not oppose heaven, they are granted amnesty when the army comes, and they are ultimately employed on behalf of the nation, fighting other bandits—they are no longer bandits ‘Acting for Heaven and Exercising Morality.’ They have at last become slaves.”13 At last we come to the point! It is lucky that The Wandering Earth has drawn out such lofty dreams, heavy with the hope of saving all humanity, while also drawing out those over-ambitious, narrow patriots proclaiming the hegemony of China over the world, as well as the fake internationalists. This is truly a magic mirror, allowing us to see through the conspiracy! It is only the true patriots and real internationalists, not placing their own country above others and seeking the real unity of the entire world, who have had the courage to give deep thought to The Wandering Earth and say “no,” critiquing the film and critiquing themselves. This is never an easy task, since it requires that you be strict with yourself. However, these nationalist youth happily dancing across the stage are in reality not completely useless. In fact, they may be able to act as the main force of a New Democratic Revolution. But since the husk is so severely rotten, it will never be able to contain them, and they will have an urge to burst through the cocoon. We will then be able to act as the vanguard of the next socialist transformation. The lesson of history is that people never learn the lesson of history. We might as well wait and see.

Notes from Chuang

- Tootopia was probably the most popular platform for Chinese left millennials until it was shut down by censors in a wave of repression earlier this year.

- Douban is a major Chinese social media network and includes a feature for user rankings of popular media. The reference here is to a recent controversy, in which some have accused users of receiving bribes in exchange for giving The Wandering Earth a low rating on Douban, and/or changing previously good reviews into bad ones. Despite little evidence, Douban was forced to respond to the accusations, though it’s unclear if any action was taken. Also note that the original Chinese has been simplified here. The original (自诩文艺青年的豆瓣瓜友们) is more literally translated as self-satisfied Douban Hipsters eating melon on the sidelines, referring to the phrase 吃瓜群众, (literally: melon-eating masses) which evokes the image of people eating melon on the sidelines as they watch the spectacle of great events passing by. The connotation is similar to the English word “sheeple,” but more specifically refers to ignorant spectators, rather than just ignorant masses in general.

- This is an abbreviation of the author’s own phrase: “自带干粮的五毛党”, the final three characters, wumaodang (the “50 Cent Party”) are a shorthand for online propagandists of official positions, who were once rumored to be paid fifty cents for every post they made in support of the regime. The first three characters zidai ganliang (literally “who bring their own rations”) implies that these posters are doing the work of the 50 Cent Party, but for free. An English-language Wikipedia page is available with more detail on the history of the 50 Cent Party: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/50_Cent_Party>

- The Self-Strengthening Movement was an effort at reform undertaken during the late Qing dynasty, following the defeat of China in the Opium Wars and the turmoil caused by the Taiping rebellion. Li Hongzhang and Zeng Guofan were both military generals and scholar-officials, each having led efforts to suppress the Taiping rebels and then to support economic and military modernization. The Self-Strengthening Movement was, in some respects, comparable to the Meiji Restoration in Japan, but was in others far more limited: it sought to largely keep political structures and cultural practices intact, purely engaging in a technical modernization of the economy and military. Though influential for later reformists, it was proven a definitive failure after China’s defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). The author uses it here as an example of an attempt to force limited reform while preventing a change in the political structure and maintaining conservative cultural practices, describing the Self-Strengthening Movement as “力挽狂澜”(liwankuanglan), literally “pulling strongly against a furious tide,” or exerting all one’s energy to save a desperate situation. The opposing reference used here is to the New Culture Movement, a later reformist effort that included both liberals and the far-left, and was based in a more complete modernization, founded on the reinvention of culture from the ground up using modern (often Western) practices, and emphasizing things like vernacular literature and an engagement with Western philosophical and political schools. The author notes both the involvement of Hu Shi, a prominent liberal and later supporter of the Nationalists (fleeing with them to Taiwan, where he became a well-known academic), as well Chen Duxiu, founder of the Chinese Communist Party.

- The term 鸡汤, literally “chicken soup” is a reference to “chicken soup for the soul” as translated from the English book series of the same name. But the term has come to be used more widely in Chinese for any ideology aimed to boosting optimism that your life will improve through individual effort, soothing discontent about economic hardship by perpetuating Horatio Alger stories and the myth of “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps.”

- These sarcastic criticisms all involve wordplay in the original Chinese, which has only been loosely reproduced here. The term for “hard sci-fi” is “硬核科幻” (yinghe kehuan), and the criticisms each play with alternate forms that use 硬, meaning hard, stiff, firm, etc.: 硬要(yingyao) to try hard to do something, 硬壳 (yingke) a crust or hard shell, and the combination of 硬(ying) and 套 (tao), the latter a verb meaning both to envelope, sheathe or encase, as well as to copy. Similarly, the term translated here as “clickbait” in Chinese is 流量 (liuliang), just meaning mobile data, but here refers to its use in the term 刷流量 (shualiuliang) which means something like “click farming.” This creates a pun with the film’s title, since the word for “wandering,” 流浪 (liulang), sounds almost identical.

- The original Chinese for the quoted “Confucian” phrases above (亲疏有别、亲亲相隐) are not actually derived from Confucius, but are instead mostly quotes about Confucianism popularized during the Cultural Revolution. Meanwhile, the use of “social and biological determinism” here is an assumption of the author’s meaning. The original Chinese is simply (出身论血统论), but both these terms (chushenlun and xuetonglun) were opposing theories of “determinism” during the Cultural Revolution. The author seems to be using them interchangeably here, however, just to indicate a general determinism about one’s social class and status.

- Both of these are set phrases derived from Chinese history. Their original form did not imply modern connotations of racial difference or nationalism, but they seem to have gained some degree of this meaning through later use, as indicated by the author’s use of these phrases here. The original Chinese is “非我族类,其心必异” and “犯我强汉,虽远必诛” respectively.

- The term “embarrassed to death” here is a very distant translation of a Chinese internet phrase often used to describe particularly hackneyed aspects of film and television: “尴尬癌犯 (ganga aifan)” literally translated as something like “cancerously embarrassed,” with the connotation that the embarrassment (尴尬) is a cancer-like (癌) violation (犯).

- This story was originally posted on Weibo, and can be found on the Western internet here: <http://www.dapenti.com/blog/more.asp?name=xilei&id=138522>

- This refers to the famous bet between the Monkey King Sun Wukong and the Buddha, in which Sun bets the Buddha that he can escape the Buddha’s palm. He runs to the edge of the earth, finding five pillars, and carves his name there. Thinking that he’d succeeded, he returns and discovers that the pillars were the Buddha’s fingers. The Buddha then imprisons him underneath a mountain for five hundred years.

- The Quotation is from Mao Zedong, spoken in 1975 during the final year of the “long” Cultural Revolution. During the Cultural Revolution The Water Margin was included in a wide-ranging campaign to critique the Chinese classics, and students were instructed to “Critique The Water Margin, and criticize Song Jiang” (Song Jiang is the novel’s hero). For more on the source of the quote, and an overview of the novel’s reception in the Cultural Revolution, see: “毛泽东评《水浒传》:这部书好就好在投降” <http://dangshi.people.com.cn/n/2014/0404/c85037-24828947.html>

- This quotation is from one of Lu Xun’s essays on literature: 鲁迅, “流氓的变迁”, 鲁迅文集·杂文集·三闲集. <http://www.ziyexing.com/luxun/sanxianji/luxun_zw_sanxianji_32.htm>