Image from SocialBikeshare.org

Translation of Jianjiao’s commentary on the collapse of all but two of the many bike-share companies that bubbled up last year, and on the discourse of the hard-working, risk-taking CEO, followed by our own observations.

‘Women workers have a say: Bluegogo’s CEO has apologised, but I still haven’t gotten my wages and can’t pay rent’ (女工说:小蓝单车CEO道歉了,但我还是没拿到工资付房租)

By Li Zhi (李芝), from Jianjiao (尖椒部落), 22 November 2017

Translated by Go Slow Notes

The workers at the Jiangnan Leather Factory ended up selling wallets, my uncle sold shoes, and now Bluegogo’s former employees are selling furniture. It doesn’t matter if it’s the boss fleeing with the money or the business’s failure on the market, the result is always the same: the ordinary workers get screwed.

Bluegogo, often called “the bike-sharing company with the best bicycles,” has dissolved. The CEO Li Gang first disappeared and then eventually sent an apology, as if this were the end of the matter.

After notification about the company’s dissolution, however, it was revealed that Bluegogo workers had resorted to selling second-hand furniture in order to get by. They were forced to do this because their Bluegogo wages were in arrears and were likely to remain unpaid until February 2018.

Seeing this news, some netizens expressed concern that if the workers were still not paid by February, many of them would be unable to go home for the [Chinese] New Year!

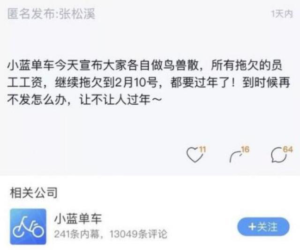

“Bluegogo announced today that wages won’t be paid until February 10 — almost New Year [February 16]! If it turns out we still aren’t paid by then, what will we do?”

Winter has come for the bike-sharing economy

In early June this year, Wukong Bike announced its withdrawal from the bike-sharing market. Since then the ‘death list’ of bike-share companies has continued to grow: in mid June 3Vbike closed down; early August saw Tingting Bike disappear; then going into September Kuqi Bike, Bluegogo and Xiaoming Bike declared financial difficulties one after the other, resulting in complications in returning user deposits.

Although known as ‘the third top company in the industry’, Bluegogo has now also announced that it has ceased activities. This has prompted the media to report on a ‘crisis of the bike-sharing economy’.

It did not take long for this crisis to emerge. The first [dockless, app-based] share bikes appeared in 2014.[1] By 2016, competition within the share bike economy was already at a very high level. When the bike-sharing economy reached its peak, all first-tier cities were covered with share bikes.

Soon however, by 2017, several bike-sharing companies had already begun to cease operations and disappear. As a result, there are now many share-bike users who have not had their deposits returned, and many workers whose wages have not been paid, with nowhere to direct their grievances.

Bluegogo’s brief life illustrates the bike-sharing economy’s cycle of competition and elimination:

2016/11/22: Bluegogo holds a news conference and launches in Shenzhen

2016/12/13: launch in Guangzhou

2016/12/19: launch in Chengdu

2017/1/11: launch in Nanjing

2017/1/18: launch in Foshan

2017/1/25: launch in San Francisco

2017/2/21: enters Beijing

2017/2/24: Bluegogo announces round B financing of 400 million yuan

2017/11: announces termination of operations.

Bluegogo did not survive for even one full year. When it closed, some observers lamented that there was no big financial backer to save the company, while others worried about the bike users who would not see their deposits returned. It seemed that no one was concerned that the workers had lost their jobs or that their wages remained unpaid.

The predictable consequences of monopoly[2]

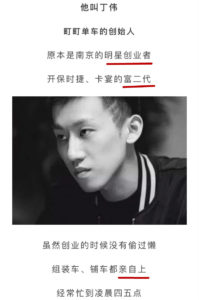

Even before the Bluegogo scandal, Ding Wei, the founder of Tingting Bike, was accused of illegally raising funds for the company and spent 40 days in detention. (Later he denied this charge, saying the reason for his detention was actually related to his father’s company.)

Before the legal controversy with Tingting Bike’s fundraising emerged, Ding Wei was Nanjing’s most famous millennial entrepreneur. After the controversy became public, the commentary was circulated online:

[Translation of screenshots:] “His name is Ding Wei. He is the founder of Tingting Bike. Formerly known as Nanjing’s most famous entrepreneur. Porsche-driving son of rich parents. While running his business he never slacked off, often working until four or five in the morning, directly involved in the bicycles’ assembly and distribution, then going into work again the next day. He really wanted to make this project work. Yet because of problems with capital flows and the entrance of Mobike and Ofo into the market, his dream came crashing down.”

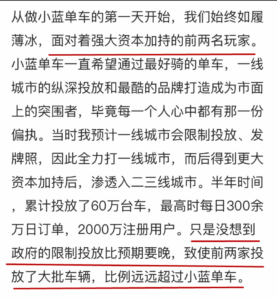

[Similarly,] when Bluegogo’s CEO sent his apology after disappearing, it included the following paragraph:

[Only underlined phrases translated] “Since day one… Bluegogo always had to face the two biggest competitors…. We didn’t realise the government restrictions on bike numbers would come so late, so the two largest companies put many more bikes into circulation than Bluegogo could.”

[Only underlined phrases translated] “Since day one… Bluegogo always had to face the two biggest competitors…. We didn’t realise the government restrictions on bike numbers would come so late, so the two largest companies put many more bikes into circulation than Bluegogo could.”

Li Gang thinks that the most important cause of Bluegogo’s failure was the competition from Mobike and Ofo. It is true that to compete on the market you need to possess a large amount of capital, you need to keep pouring it into the company in order to dominate the market. In 2016 it still seemed as though many companies could contend in the share bike-sharing economy. Within a year, however, the concentration of capital and domination by certain companies of the bike-sharing market has become obvious. Except for Mobike and Ofo, all other bike-sharing companies had successively collapsed and disappeared. Mobike essentially belongs to Daddy Jack Ma and Ofo to Daddy Ma Huateng. So in the end, the competition is only between these two big daddies surnamed Ma.

Mobike & Ofo

Although this reality is difficult, the failed entrepreneurs must have known that these ventures necessarily entail a risk. They were eager to compete and succeed on the bike-sharing market. But they should be held responsible for the consequences of the company failures.

But we see in commentaries such as these, it’s as if these children of the rich should be forgiven just for having the experience of failure, and as if some previous hard work should excuse them of any responsibility. I refuse to accept this line of argument. These entrepreneurs come from and possess large amounts of capital, and yet it is the workers and users of the bikes who bear the consequences of their failures. Why should I forgive them?

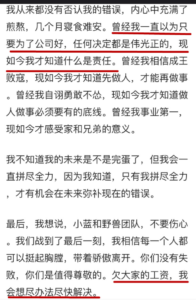

In his apology, Li Gang wrote [summarized below]:

The bold and energetic Li Gang’s only concerns were with improving the company, and all his decisions were great, glorious and correct (伟光正). It was only after the failure of Bluegogo that he realised what role his decisions played in the collapse of the company. And even though he did come to admit responsibility, all he had to offer the workers was the weak promise, “I’ll try to sort it out soon.” Anyone paying attention will know that this means there is no real plan in place to do anything.

Li Gang is able to write an apology like this, which appears to be serious but in fact evades all aspects of accountability. Meanwhile he disappears, residing overseas beyond the consequences of the company’s collapse. And yet the workers are left waiting for wages they need to pay rent and buy food.

Boss, I’m still waiting for my wages to pay rent

‘Jiangnan Leather Factory’, a song that’s become a popular meme online, has these lyrics:

[Below is our translation of the entire song rather than the selection included in the article. Listen to our favorite version of the song here or in the video embedded below.]

浙江温州 浙江温州

In Wenzhou City, Zhejiang Province

江南皮革厂倒闭了

The Jiangnan Leather Factory’s closed down

浙江温州 最大皮革厂

The biggest leather goods factory in the province

江南皮革厂倒闭了

The Jiangnan Leather Factory’s closed down

王八蛋王八蛋黄鹤老板

Our piece of shit boss Huang He

吃喝嫖赌吃喝嫖赌

Was always wining and dining, gambling and whoring

欠下了欠下了3.5亿

350 million yuan in debt

带着他的小姨子跑了

He ran away with his mistress

我们没有没有没有办法办法

We’re screwed, there’s nothing else we can do

拿着钱包抵工资工资

So we took these wallets in lieu of our wages

原价都是100多 200多300多的钱包

Wallets worth 100, 200, 300 yuan

统统20块

We’re selling them all for only 20 yuan each

20块20块统统20块统统统统统统20块

20 yuan, 20 yuan, all for 20 yuan…

黄鹤王八蛋 王八蛋黄鹤你不是你不是你不是人

You piece of shit Huang He, you’re not a human being

我们辛辛苦苦干了 辛辛苦苦给你给你干了大半年

We worked our asses off for you for over half a year

你你你不发不发工资工资

Pay us the money you owe us

你还我还我血汗钱!

That we earned with our sweat and blood!

It is true that the lyrics of this song were originally used to sell counterfeit wallets on the street, but less well known is that there actually was a boss named Huang He who ran away without paying his workers. A factory boss had fled and the workers were thrown into hardship: this is the [somber] reality behind this [often frivolously presented] song.

My parent’s generation basically all left the countryside for work and would only return at the end of the year. I remember one year, my mother suddenly asked me to go to my uncle’s house to buy a pair of leather shoes. I was happy but also a bit confused, because my family was poor, and my mother rarely spent money. But now she was telling me to buy new leather shoes when I already had an old pair of sneakers that were fine.

Later I learned that this was because my uncle’s boss at the factory had run away without paying their wages for half a year. Come the end of the year, the workers had nothing so took the shoes from the factory [back to their hometowns] and sold them themselves [on the street]. Even though many passersby stopped to look at the shoes, few actually bought them, and in the end not enough were sold even to cover the cost of transporting them home. That year, my uncle had to borrow money to buy meat for the New Year’s meals, as well as tuition for his kids and other everyday expenses. None of this hardship was of his own making.

The workers at the Jiangnan Leather Factory ended up selling wallets, my uncle sold shoes, and now Bluegogo’s former employees are selling furniture. It doesn’t matter if it’s the boss fleeing with the money or the business’s failure on the market, the result is always the same: the ordinary workers get screwed.

Who cares about the workers’ situation, and what can they do to protect themselves?

Commentary by Chuǎng

This piece from the left-feminist WeChat feed Jianjiao is an artifact of workers left in the dust of bankruptcy without pay in China’s new “sharing economy” after the high-profile collapse of Bluegogo. The author reflects on the issue of wage arrears, faced by so many workers of the previous generation in the manufacturing sector, as in the shoe factory whose boss fled without paying half a year’s wages to the author’s uncle.

The text shows increasingly rapid cycles of boom and bust in China’s “new economy.” These result from the movement of surplus capital from manufacturing into the service sector, from ride-sharing to bike-sharing and from parcel delivery to food delivery. The cycles of mass investment and fierce competition for market share, saturation and homogenisation of product lines, followed by monopolisation by one or two key players and elimination of the competitors that fall behind, like Bluegogo and its workers left without pay: these are the common dynamics of capital accumulation at work still in bike sharing as they were in the days when manufacturing played a greater role—only now at greater velocity.

Wage arrears plagued China’s bicycle manufacturers throughout the year. In the Hebei town of Wangqingtuo, known as the nation’s “number one bike town,” 75% of its local GDP and 60% of its workforce had become dependent upon bike production, but now mass closures have hit the town in two waves. On the one hand, the rise of bike-sharing pushed down individual purchases of bicycles and thus hurt factories producing for the consumer market. Meanwhile, the sharing market’s rapid expansion first caused an explosion in orders at factories producing for these new companies, providing relatively high wages for the workers, but before long the old problem of expansion and overcapacity struck, leaving closures, layoffs and wage arrears in its wake.

The article translated here represents a segment of young people in China beginning to articulate left perspectives on changing conditions of work under contemporary economic conditions. It resonates with contemporary debates elsewhere about conditions of so-called “post-Fordist capitalism,” “sharing economies,” and relations between labour and capital in these contexts. Academics and leftists have placed varying degrees of hope on the potentials of share economies, some lamenting the rearrangements of labour that render the new economies unfamiliar to old models of organising, while others see the rise of intangible commodities as qualitatively new conditions of capital accumulation. The article below is not explicitly concerned with these questions, but the commonplace questions it raises allow us to see how the intangible can be very concrete, both in workers’ concerns about access to everyday necessities and in the cycles of competition, accumulation and elimination as they have played out in these new sectors.

While theorists have highlighted the differences between “new” and “old” arrangements of work, this article presents a critique of the proletarian condition in today’s China that threads across that division. The frustrations and anger of working life that emerge from this condition continue to circulate through experiences of the factory and the sharing economy alike. There is no easy answer here, only the documentation of these frustrations alongside the dark humor of memes such as the “Jiangnan Leather Factory” song.

Translators’ notes:

[1] Traditional docked public bike systems have been operated by local governments in several Chinese cities since 2007, with Hangzhou boasting the world’s largest bike-sharing network of with 3,572 stations, 84,100 bikes and 310,000 users per day as of 2016. See ‘China’s bike-sharing bust’ and ‘Bicycle-sharing system: programs in China’.

[2] This is a direct translation of the original section title. The author is possibly alluding to the dominance of two of China’s largest capitalists coming to dominate, predictably, the bike sharing economy. However, it is a bit misleading, in that while the account of events arguably shows a tendency towards monopoly, especially now that there is a potential merger between the major two remaining bike companies, it does not narrate a situation that could be described as the consequence of monopoly.