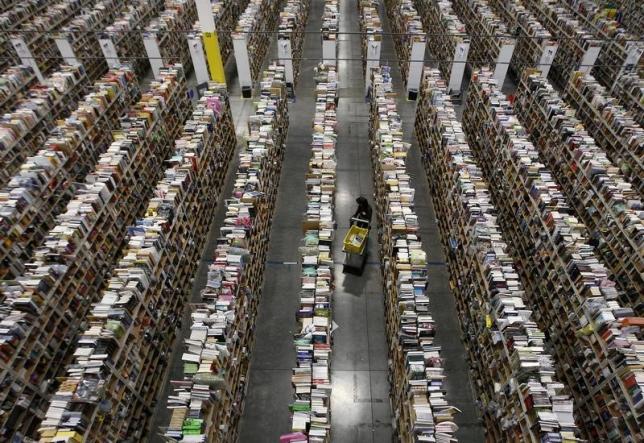

Photo from Reuters/Ralph D. Freso

Results of an inquiry into the situation of Amazon warehouse workers in China—part of a project on ecommerce, logistics and supply chains by the “Inbound/Outbound Notes” collective.

—

Amazon has long been in the news – for its giant size, its rapid growth, its silly new inventions of drones and talking buttons for placing orders. Amazon’s employees have shifted the spotlight from the consumer perspective to their own working conditions. They’ve moved from quietly sweating away behind the walls of Amazon’s massive “fulfillment centers” to speaking out and eventually fighting back against the monotony of picking and packing, of being bullied around and treated like children by managers, against low wages and long hours, against changing shifts and short breaks and so on. Workers in Germany, Poland and France have gone on strike or used other collective actions, such as slowdowns, to assert their demands and resist intimidation by this seemingly all-powerful exploiter.[1]

A lot of goods that Amazon ships to American, European and Japanese customers are made in China. And here too, Amazon has been trying to establish roots. However, in China, Amazon is a dwarf and light years away from the dominating position it holds elsewhere. Still, Amazon’s global reach coupled with its workers’ struggles and networking efforts elsewhere make it a particularly interesting case for comparing work conditions and for exchange among workers in different parts of the world. This article draws on conversations with workers in European and Chinese warehouses and makes some comparisons.

And what’s far more important than an interesting case to study and compare are the readers to whom we hope to provide an insight into the working conditions of their Chinese colleagues. Around the globe wherever we spoke to Amazon workers in France, Germany, Britain, Poland, Spain, Japan and China, they were eager to learn about their colleagues in other countries and how their situations compared. Amazon thus not only creates the same standardized working conditions in warehouses around the globe, it also creates workers’ interest in learning about each other and getting in touch. Workers from warehouses in Germany, Poland and France meet regularly these days and talk directly with one other. Since Asia, Europe and North America are a bit further apart then a few hours driving, we want to help bridge the gap and describe the work and life of Amazon workers in Chinese warehouses to their workmates.

We were able to meet about a dozen workers from an Amazon warehouse in China on multiple occasions over the course of several months. They told us about their work and their lives, and we shared with them a few stories about Amazon warehouses from our friends in other countries. Our encounter began with an unexpected misunderstanding: the Chinese workers assumed our friends in European Amazon warehouses must all be managers, and that the sort of work they do in China would be done by robots in Europe. They could not believe that workers in Germany or France would do the same tedious and exhausting physical work that they do, so we used pictures, videos and stories from our friends to show this. The following report is based on what evolved from this encounter.

Amazon in China

In 2004 Amazon first entered the Chinese market by buying Joyo.com. This was the 7th regional online platform by Amazon after those in the USA, Canada, France, Germany, Japan and the UK. Joyo.com had started as a website for downloading software and quickly became China’s 33rd most popular website. In 2000 Joyo.com started selling books online, first in Beijing, then Shanghai and eventually Guangzhou. In 2007 Joyo.com was renamed Amazon.cn.

Today, China is the world’s largest ecommerce market, with US$589.6 billion in sales originating from Chinese vendors in 2015, a 33% year-over-year increase, according to the National Bureau of Statistics.[2] Especially young people do much — if not most — of their shopping online, from clothes to books to electronics and even fruit.

In this huge market, Amazon is a relatively small player. According to McKinsey, in 2015 Amazon China employed about 5,500 people[3] and had a small market share compared to the situation in the US and Western Europe. While the Chinese companies Alibaba and JD.com control about 54% and 23%[4] of China’s online retail market, respectively, as of 2015, Amazon’s market share was only about 1.1 to 1.5%, ranking 5th or 6th place among online retail platforms.[5] Given this tiny market share, Amazon would not be the first choice if one’s goal were purely to investigate working conditions in Chinese ecommerce.

One major difference between Amazon and Alibaba’s retail services is that the latter function almost entirely as platforms for independent vendors to set up their own online stores. Taobao.com and its rural variant Cun.Taobao.com are “C2C” (consumer to consumer) platforms like eBay, allowing any of the website’s 400 million users to set up their own shops with little capital or experience, often selling homemade products like soap or jewelry that would be unavailable elsewhere. Although Taobao’s spin-off platforms Tmall.com and Tmall.hk are classified as “B2C” (business to consumer), they still differ from Amazon in that the overwhelming majority of their orders are processed not through Tmall’s own “Supermarket,” but through 50,000 different shops run by companies such as Uniqlo or Nike. Alibaba’s founder Jack Ma has argued that this business model has provided an advantage over companies like Amazon, which has to process and warehouse most of its own orders.[6]

Although in recent years, Amazon has opened up its platforms to more third-party vendors, in China it still lacks the multitude of personal, political and economic connections along the supply chain that have made companies like Alibaba and JD.com so successful. Such connections and experience have, for example, facilitated the creation—often by government initiative—of over 1,000 “Taobao villages,” where the entire economy has become reorganized around the production, warehousing, sale and delivery of commodities via Taobao and affiliated logistics companies, from which Alibaba’s shareholders get a cut at multiple steps along the way.[7] This is something Amazon has no hope of emulating in China—at least not in the near future.

Amazon started with selling books and then expanded to selling all sorts of other stuff. From the very beginning, its business included warehousing and packing goods. In 2006, Amazon opened up to third party vendors who either organize shipping of their products themselves or have Amazon handle it. In 2016 “marketplace sellers,” i.e. third party vendors, made up 40% or more of all Amazon sales.

Common problems with independent sellers in online marketplaces are fake products or poor quality. Shoppers have difficulties reaching out to the sellers. This happens with independent sellers on Amazon in Europe and even more so with Taobao. A large portion of the products offered on Taobao are cheap, but many are fake or of low quality. A Chinese state survey in 2015 found only 37% of products on Taobao to be genuine.[8] In contrast, Amazon’s status as a major American company gives it the reputation of delivering higher quality goods. However, there are other Chinese ecommerce companies such as JD.com that are also considered more trustworthy than Taobao and where people would turn in order to buy certain products such as electronics. Another problem that Amazon faces in China is that its shipping is comparably slow because it neither operates its own parcel delivery system (as JD does) nor does it cooperate with delivery companies as closely as its rivals (such as Alibaba). Its main transport provider among others is Shunfeng. At the same time as Amazon is expanding into delivery in the US and some European countries, it is also trying to do the same in China and already operates its own “Amazon Prime” delivery service called yuanpei (原配) which serves only central areas of certain major cities. Both the workers we talked to and other Chinese consumers often mention Amazon’s lack of a speedy delivery service as the company’s disadvantage in comparison with its rivals. This is remarkable considering that Amazon’s major advantage in Europe is generally considered to be the speed of its deliveries.

In central areas of a few cities, Amazon.cn does some of its own delivery for “Prime” customers (Photo: Maosuit.com)

Amazon is also expanding its business into trans-pacific ecommerce. The company is preparing to operate as a middleman across the Pacific Ocean for companies delivering goods between China and US to sell them on the Amazon marketplace—an arrangement known as “cross-border ecommerce.” By August, Chinese customers had placed more than 10 million orders for overseas items through direct delivery at Amazon.com. Cross-border sales in the first half-year in China have seen rocketing growth, a year-over-year increase of 400 percent.[9] On the other coast, US online shoppers will spend about US$30 billion this year on cross-border transactions. That’s a 10 percent increase from 2015, with China the leading source of goods purchased, according to a February report by EMarketer.[10] For a giant like Amazon with few remaining markets into which it could still expand, cross-border ecommerce seems to be the new frontier for potential growth. But Alibaba is not far behind Amazon on this front: AliExpress, Alibaba’s new online marketplace in the UK, now allows Chinese vendors to sell directly to UK buyers and deliver to their doorstep at very low shipping costs. And in January 2017, Alibaba held talks with the Bulgarian government about possibly opening a warehouse in Bulgaria to serve the European market.[11]

According to MWPVL International, Amazon operates 17 warehouses in China[12] , but the numbers concerning China are not entirely accurate as we know of at least one warehouse included in this number that actually closed in 2014. Most of the warehouses in China are located near Tier 1 cities or other big cities e.g. Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Tianjin, Wuhan, Chengdu and Nanning.

Amazon in “City X”[13]

Amazon opened the first warehouse in “Y Province,” “FC1,” in the late 2000s in the capital city’s main industrial district. Later a second warehouse opened, “FC2,” and finally the first one closed, leaving FC2 as Amazon’s only warehouse in the province. It is reported to have an area of less than 100,000 square feet, but we could not verify that with workers. Including management, about 400 people work there, including over 200 on the warehouse shopfloor and 150 in the office. The workers we talked to estimate that 70% of the products FC2 processes are books, with a variety of other commodities making up the remainder.

FC2 shares a logistics park with five or six other warehouses, almost all for ecommerce platforms, including one operated by JD. Some of the other warehouse companies have dormitories inside the precinct but Amazon does not offer dormitory accommodation. There are a few factories in the area around the warehouse compound. Residential neighborhoods are within a short walking distance, along with a major bus stop and a metro station roughly 20 minutes away. Many of the Amazon shopfloor workers live in a nearby village. There, most of the residents are migrants from neighboring other provinces who rent rooms from the local villagers.

Work Organization

Considering Amazon’s high degree of standardization, it’s no surprise that the work in FC2 closely resembles that in Amazon warehouses we’re familiar with in other countries. Work is divided into two main sections: Inbound and Outbound. The three largest Inbound departments (known as “teams”) are Receive (收货) — unloading pallets from trucks —, Sort (分件) — upacking, checking-in and sorting the products (分件) — and Stow (上架) — moving the products to their designated places in the warehouse and putting them on storage racks. In Outbound most workers work either in Pick (捡货)— selecting items from shelves — or Pack (包装). The Pack department is divided into rebin (配货), SP (包装) and SV (打包裹单) — these subsections handle packages containing single or multiple items separately. Apart from these main departments there are also other sections handling customer Return (返厂), Problem Solving (问题解决), Flow Control (流程控制), Training (培训), and Quality Control (质检). The separation between Inbound and Outbound seems fairly large, “like two separate worlds” as one worker put it. At times someone from Inbound will be transferred to Outbound because of personnel shortage, but workers told us that this rarely occurs. Workers in Outbound know each other because they have to interact regularly across different departments, but they have little interaction with colleagues from Inbound.

Every step in handling items and fulfilling customer orders requires workers to scan each item using a handheld scanner (扫描枪). Every step is registered with the warehouse’s computer system, and managers can always look up who processed which item at what time. This way, Managers always know how fast each worker is working and where, in the jungle of warehouse shelves, she is just about to pick the next item. All positions in the warehouse require workers to stand or walk. Workers told us that picking items from shelves is probably the most exhausting position, requiring them to walk between 10 and 15 km per shift on average, often while pulling or pushing a cart or even two carts if an order is too big to fit into one. The work process is standardized using SOPs (standard operation procedures), as in all other Amazon warehouses. In FC2 they use SOPs from the United States, but the level of automation in FC2 is lower, so they have to rewrite them according to local conditions.

Workers in each department are trained in how to work in other departments. Workers from Pack, for example, are trained to work in Pick. If the manager finds that a certain worker performs faster or “better” in another department, she may be permanently transferred there. We spoke to workers who saw this as a good opportunity that Amazon offers for them to develop new skills, while others pointed out that the company does this for its own benefit.

Almost all shopfloor workers and department heads (known as “team leaders” or “TLs”) whom we talked to came from other provinces or rural regions of Y Province, only one office worker grew up in City X. Although many workers have been living and working in City X for many years, they don’t have hukou (household registration) there which would entitle them to local social services such as free public schooling for their children. One worker told us that hardly anyone over 35 is recruited because even basic-level jobs (pugong, level zero or one in Amazon’s ranking system) require at least junior secondary education (chuzhong) and the ability to read some English, which older workers are less likely to have. Most of the office workers are fresh out of college, whereas most of the shopfloor workers are in their late 20s and early 30s. In terms of gender, there are more women than men in every shopfloor department except for Stow, which requires heavy lifting. Amazon limits the weight female workers are allowed to lift to 10 kg, in contrast with 15 kg for men, although this is not required by Chinese Labor Law (as it is in Poland, for example).

Wages and Working Hours

The basic monthly wage on the warehouse shopfloor, which is called “level zero,” starts at about 10-15% above the local minimum wage and after 6 months there is a pay rise of another 10% of the local minimum wage, with further increases every 6 months until it reaches the maximum of a little more than 1.5 times the local minimum wage. Adding overtime and bonuses, a shopfloor worker can make between 150 and 200% of local minimum wage a month, and a TL can make between 150% and 250% of local minimum wage per month, averaging about 200%. The wages for office workers start at level 3. One office worker we talked to earns a basic monthly wage of over 200% of local minimum wage at level 4.

Wages are composed of a basic wage in addition to overtime (1.5 times the basic hourly wage for regular overtime and 3 times the basic wage for holidays), a tri-monthly bonus and a high temperature subsidy (120-130 yuan per month – lower than the legal requirement of 150). For night shifts, a subsidy of 12 yuan is paid per day if the work goes after midnight. In addition, Amazon pays a food subsidy of 7 yuan per day with each meal costing 6-7 yuan at the logistics park’s shared canteen (run by an outside company), but workers said the food sucks. Bonuses are officially said to be calculated for each individual worker based on 3 factors (work speed, attendance and frequency of mistakes), but the results are not announced publicly in the warehouse. Actual bonuses range between zero to 80% of one month’s minimum wage per 3 months. Workers find it unclear how their bonuses are actually calculated, but they do know that they lose their bonuses if they take too many days off from work for paid sick leave or vacation time during the three months when a bonus is calculated.

We asked workers how they get by with their wages and learned that some can economize and live on as little as half the minimum wage each month, but most usually spend a month’s minimum wage on expenses such as rent and food, with rent for a single room in the area around 20-25% of the monthly minimum wage. One worker, who said he wants to enjoy life while he’s still young, said he normally spends between 100% to 150% of the minimum wage each month due to additional expenses such as alcohol and cigarettes. These living expenses are similar to those of workers in other industrial areas of City X, except that the rent is a little higher in FC2’s neighborhood than in industrial districts further away from the city centre.

According to workers we talked to, FC2 defines regular working hours (before overtime sets in) as 166.64 hours per month. (This is said to be based on 8 hours a day times 21.75, because the state labor regulations define a working month as 21.75 days, although this would add up to 174 hours per month.) Workers get at least 30 minutes for lunch, sometimes more if it’s not busy; they clock in and out for lunch, but there is no penalty for clocking in late afterwards. Office workers have regular working hours from 9 AM to 5:30 PM. Warehouse workers have changing shifts and working hours based on a “flexible scheduling system” (综合工时制), which in this case seems to mean that one has 40 hours per week, without fixed daily working hours or starting times, before overtime sets in.[14] Workers in Inbound work only day shifts (starting at various times in the morning, depending on each week’s schedule), whereas about two-thirds of Outbound workers work the night shift (starting anywhere from 3 PM to 7 PM and ending between 11 PM and 3 AM). Normally, workers have two days off per week, but during peak times they have to work six days a week. New employees start with 12 days of paid vacation per year, which increases to 15 days after 5 years working at Amazon and finally to 20 days after 10 years.

Aspects of the employment structures in Amazon warehouses vary from country to country. For example, although Amazon does not pay its warehouse workers very well, it does usually pay a little more than other big employers of unskilled or semiskilled labor in the area, including other warehouses. Amazon preferably chooses regions with rather high unemployment for its warehouses and then pays a little more. In East Germany, for instance, it pays 10.30 euro compared to basic-level work on a pig farm for the minimum wage of 8.50 euro per hour. What seems to be consistent with the situation in City X is that Amazon tries to be a little better than the worst-paying employers in the region – according to what workers told us.

Contracts

Regular warehouse shopfloor workers (as opposed to both office workers and the occasional temp agency workers) are not directly employed by Amazon, but by a company we’ll called “City X Logistics” (CXL), which also owns the logistics park in which FC2 is located, including the warehouse building itself. They are given one or two year contracts. During busy periods such as the weeks leading up to “Singles Day” (November 11), FC2 also hires temporary workers from a certain labor dispatch agency. For example, in the Pack department, where about 50 regular workers are employed in total (with less than 10 working day shifts and over 20 working evening shifts), during one busy period the workers told us about, FC2 hired 8 agency workers, and during an even busier period it hired as many as 30. Office workers, on the other hand, sign permanent contracts with Amazon when they are first employed.

In European warehouses, Amazon employs many permanent workers on the shopfloor. In German or French warehouses, up to 80% of the workers have permanent contracts, while in Poland only 50% do, with many temporary workers employed by agencies. Often, Amazon starts hiring only workers on fixed-term contracts for a new warehouse, but over time they have to make an increasing number of workers permanent because of labor law requirements and the shortage of available workers. The latter reason is linked to the seasonal aspects of ecommerce in countries that celebrate Christmas. Starting in October, Amazon has to hire additional staff to handle the extra workload, only to fire most of them on Christmas day. Several years into this hiring-firing cycle, it becomes increasingly difficult for Amazon to find new workers for Christmas in the area around its warehouses and has to look as far as 1.5 hours away in one-way commuting time. In other words, the seasonal peaks require a seasonal high turnover that becomes increasingly difficult to fulfill, so Amazon has to organize its non-seasonal business on a more permanent basis to reduce the overall turnover.

In City X, Amazon signs permanent contracts with all 150 of its office employees, but none of its warehouse shopfloor workers. Chinese Labor Law requires employers to offer permanent contracts to its employees after the completion of two fixed-terms contracts – as in Germany and many other countries. None of the workers we talked to, however, had worked at FC2 for more than two contract periods, although a few had previously worked at FC1 (the old warehouse, now closed), where they had signed contracts with Amazon rather than CXL. This may be one reason why FC2 switched its shopfloor contracts from Amazon itself to CXL in 2014. At that time some shopfloor workers who had previously signed with Amazon at FC1 were transferred to FC2 and given new contracts with CXL to sign.

City X’s labor market provides Amazon with huge numbers of migrant workers – between ten and thirty million for the region as a whole. Because of the small size of Amazon’s workforce compared to the size of the labor market, hiring on fixed-term contracts does not face the same difficulties of a limited labor market as for warehouses in Europe. Here, Amazon only has to compete on the terrain of pay and working conditions. And in this it seems to be doing quite well, because we did not hear about Amazon having problems hiring warehouse workers here.

Managerial Control and Workers’ Grievances

Concerning penalties and pressure put on workers, none of those we talked to had heard about people getting fired. Rather, as one worker told us, Amazon’s strategy seems to be moving workers to different departments to pressure them quit on their own. In that way, the company avoids having to pay severance pay. There are security checks at the gates, and no cellphones are allowed inside the warehouse – the same as in Europe. Only TLs are allowed to have cellphones, and those are company phones rather than personal ones. Chatting is of course common among workers, although the managers try to limit it. Workers don’t wear uniforms but have to follow a dress code for safety: long hair has to be in a bun so it doesn’t get caught in the machinery, no dresses, skirts, flip-flops or sandals are allowed, shorts may not be above the knee, and workers have to wear gloves.

No union is active in the warehouse. Most of the workers had never heard of a “union,” but a few had. One way the company tries to deal with discontent is by providing feedback forms for the workers to fill out and return to their TL, but none of the workers we talked to had actually used these forms.

One point of dissatisfaction seems to be the Social Insurance arrangement.[15] According to Chinese Labor Law, both employees and employers have to pay into each employee’s Social Insurance accounts, but the share paid by employers differs between municipalities. Although the warehouse (Amazon) and the direct employer (CXL) are both located in City X, they use Social Insurance accounts based in the nearby “City Z.” The only reason for this seems to be that in City Z the mandatory employer contribution towards each employee’s account is a slightly smaller percentage of the wage than in City X. For workers, having their accounts based in City Z means that it is difficult to access services. For example, they cannot use their health insurance (one of the five components of Social Insurance) to see the doctor in City X. Instead, the company reimburses 90% of the medical fees for City X hospitals ranked at level 3 or above (三级以上).

We were surprised when workers told us that they had not heard about firing or penalizing of low work performance. Because Amazon pays hourly wages in all the warehouses we know of (as opposed to piece rate, which is used at the JD warehouse next door, for example), it has to put a lot of emphasis on increasing the work speed. Since every step from unpacking to storing, picking and packing items is registered, managers can easily look up the average speed of groups of workers and of individual workers. In order to pressure workers to work faster, managers in European warehouses set targets for the number of items to be picked or packed per hour. If workers don’t meet the targets, they often face consequences — from bonus reductions and psychological pressure through meetings with management, to sanctions or being sacked (depending on the conditions of their employment). Many workers in German, Polish and French warehouses have said that this puts a lot of pressure on new workers in particular, but over time this pressure becomes less effective as workers become desensitized or rebellious. In Germany and other countries, workers have become especially resistant to this kind of pressure through the ongoing strikes and other collective actions. Taking these actions has created the space for workers to build stronger friendships, trust and the confidence to reject management’s demands.

As with the work speed, mistakes such as picking or packing the wrong item are also traceable through the computer system. In some countries, Amazon traces these mistakes back to individual workers and penalizes them by cutting their bonuses. In the City X, however, workers did not tell us about being penalized for these kinds of mistakes during the work process. It is still unclear to us how accuracy is checked and how the management deals with mistakes made in Stow, Pick or Pack.

Over the past five years or so, more and more injuries and health problems related to the work in Amazon warehouses has become visible for workers in Germany. The exhausting process of picking and pushing a heavy cart through the warehouse wears on the skeleton and leads to back problems, as well as to aching joints and shoulders. The sick rate in German Amazon warehouses is very high, with 15-20% of workers calling in sick on any given day, on average. Mental health issues are also quite common. Despite offering bonus payments to workers who do not call in sick and show up, Amazon Germany’s attempts to lower the sick rate have been mostly unsuccessful.

When we asked about calling in sick, workers in City X told us that they can get one day sick leave per month without deductions from the monthly wage, but additional sick days lead to deductions. Amazon introduced these deductions because management believed that too many workers had been calling in sick over the past few months. It is possible that this increased frequency of people calling in sick may be related to an observation one worker made: over the three years he had worked there, the number of shopfloor workers decreased (he estimated by a few dozen workers but wasn’t sure), whereas the amount of work had stayed about the same,[16] so the pace had increased significantly. But workers could not tell us what the average sick rate is. In order to call in sick, workers have notify their TL or manager and provide a doctor’s certificate when they return to work. Unsurprisingly, they have to pay a doctor in order to get the certificate. When workers return to work after a couple of sick days managers might ask them why they were sick. Although this is a common pressure technique, some workers from FC2 felt that this was just an expression of caring.

We learned that Amazon grants pregnant workers 4 months of maternity leave, one month more than the 3 months required by China’s Labor Law. If workers take leave later than 4 months before giving birth then they can take the remaining days afterwards. The Labor Law grants additional 15 days for difficult births and for women who give birth to twins, triplets and so on. This is very little leave in comparison to Poland or Germany where pregnant women workers are sent home by Amazon and paid their full salary for 9 months. Workers from FC2 told us that quite a few became pregnant recently. Two women told us that they prefer Amazon to some employers because they follow the Labor Law in general, particularly with regard to maternity leave, and that Amazon wouldn’t find excuses to fire women when they get pregnant. One woman originally planned to quit when she got pregnant, but her manager encouraged her to stay because they needed her as a TL, so they switched her to day shift until she was ready to go on maternity leave.

In European warehouses, the strict and often ridiculous safety rules and standardized procedures are a common source of complaints. Workers in Germany told us that they feel they are being treated like children when everything from pencil to broom has its designated space marked with a line and a sign, or when every step in the work process is perfectly standardized and hardly involves any proper thinking by the workers. Workers from FC2 did not describe the standardization as frustrating – maybe because they had experienced worse conditions elsewhere or because of other reasons we don’t know.

How workers feel about Amazon: impressions and aspirations

In general, the City X-based workers we talked to have given us a surprisingly positive impression about their jobs, in contrast with what we’ve heard from and read about Amazon warehouse workers in other countries. It’s possible this could partly be a matter of trust and the desire to put on a positive face for foreigners, but in other respects some of these workers have spoken rather candidly about personal matters in their lives. In any case, we can recount a range of positive and negative details they’ve mentioned about how their work experience at Amazon has compared with other jobs they’ve had and impressions they’ve gotten of other warehouses in the area.

Almost all the employees we talked to had only the minimum middle school education (chuzhong) and no experience with logistics work before they started at Amazon, yet several of them had risen to low-level management positions and developed skills that they think might be transferable to other workplaces. Although the Level-3 position of TL requires at least a vocational high school degree (zhongzhuan) for new recruits, we met several TLs with only middle school degrees and one or two years of experience as basic-level warehouse workers (pugong, ranked at level zero or one). Office positions require at least a bachelor’s degree (benke) for new recruits, but we met a Level-4 office worker with only a vocational college degree (dazhuan) who got the position after working in Pick for a year because of good performance (coupled with personal connections).

The TL for Flow Control proclaimed glowingly that “Amazon places great value on human resource development (rencai peiyang),” in comparison with the bicycle factory where he had worked previously. That job had no future, he said: “You could work there your whole life and you’d still be in the same position.” He just happened to have quit that job in order to take care of family affairs (a common practice for migrant workers in China), and when he returned, the factory was no longer hiring but the Amazon warehouse across the street was. At first he thought of it as just another job, but eventually he recognized that it offered opportunities for advancement.

Managers encourage workers to learn all the different basic-level positions so they can be transferred at the last minute, if a worker calls in sick for example. Once someone has acquired experience in all the main departments, they become more eligible for positions in special departments such as Flow Control, Problem Solving or Training. Although these positions don’t necessarily pay more and are ranked the same as others (for example, a TL in any department is ranked as Level-3), the workers we talked to believed them to be preferable both because they allowed workers to learn skills that might be transferable to other workplaces, and because they would be better springboards for higher-level management positions. The TL of Flow Control mentioned computer programs he had learned on the job, and he was paying money he had saved up during his three years at Amazon to attend night school at a vocational college. Upon graduation, he hoped to obtain a higher-level management position at Amazon, and if not, he was optimistic about finding a better job elsewhere.

Of the ten or so employees we talked to who started out as basic-level warehouse workers, that TL for Flow Control and the Level-4 office worker had the most positive attitudes toward Amazon in general, but none of the others expressed a clearly negative attitude, especially when it came to comparison with previous jobs and neighboring warehouses. One Level-1 worker in Pack had also been at Amazon for about three years. When we first met him in the spring of 2016 he too was hoping to eventually become a manager, like a friend who had risen from the same position to middle management—mainly through his own diligence, we were told. Nearly a year later, he was still in the same position at the same wage rate, but he had finally been offered an opportunity to begin training as a TL, because two of the department’s six TLs had gone on maternity leave. Despite this new opportunity, he now seemed less concerned about trying to move up the ladder than before, and instead treated the job as simply a way to enjoy his youth in this cosmopolitan city for a few years before deciding whether to return to his small town in central China. (He was about 30 years old.)

Another worker told us that he had learned of higher paying jobs in the same area, including the JD warehouse next door, but he thinks a little extra money isn’t worth the physical and mental stress that such jobs force you to endure, or the time you’d have to waste working overtime there. Every day before and after work, he and his coworkers overhear JD managers scolding their workers through bullhorns, whereas at Amazon “it’s the computer that tells you to hurry up” (cui ni de shi diannao, bushi ren), along with the occasional one-on-one “conversation” or “warning” by a manager. Whereas Amazon workers in other countries often complain about this perhaps more insidious style of discipline, a couple of the workers we talked to considered it preferable to the more brutal alternative on display at the warehouse right next door.

Furthermore, workers described the work at the Amazon warehouse as rather safe because management put a lot of emphasis on work safety. Workers from different continents have given this common example: when someone walks down a flight of stairs she has to hold the handrail according to the company rules. Sharing this example of seemingly absurd safety regulations stimulated laughter among the Chinese workers too.

When asked whether workers would recommend Amazon to relatives and friends, as consumers, they responded that the delivery time was so slow, particular in their hometowns, that they would not recommend it. As employees, however, at least two workers we talked to got their jobs through recommendations from relatives, and one of these got a promotion relatively soon because she is from the same hometown as the general manager.

Two workers we spoke to run small online shops selling cosmetics, food and various other products on Yunji, another ecommerce site which has subcontracted Amazon to handle its warehousing. While running online shops is not uncommon in China these days, there seems to be a link between the kind of work that some workers do at Amazon and this business they do in their spare time. Despite hearing a few stories of workers’ online ventures, only one office worker we met could find the time to run her shop somewhat successfully.

At the time of writing, workers regarded Amazon’s market share as shrinking in China over the past few years, and estimated that only about one in ten Chinese people had even heard of Amazon. They had observed for a while that few new workers had been hired after many left FC2 in 2015-2016, and whenever volumes increased they had to handle an increasing amount of work with fewer workers than one or two years earlier, so work became more exhausting. Another impression one worker shared was that Amazon.cn had become increasingly dependent on selling its warehousing services to Chinese ecommerce platforms such as Yunji over the past few years, but now those platforms were building their own warehouses and so may no longer need Amazon’s services. She and some of her coworkers thought of this as a bad sign for the outlook of FC2 and the potential to move up the ladder there. After workers had received their year-end bonus in early 2017, she told us, they had started to look around for other options.

Further Exchange

When Amazon workers from Poland and Germany met to discuss strike and organizing experiences and to plan their next meeting, one Amazon worker from Germany pulled out her work schedule for the whole year to decide on a date. Another worker from Poland saw this and asked with surprise “wait, do you get work schedules for the whole year in advance?” She continued, “we only get monthly schedules because the management claims that customer orders and the work load are so unpredictable that they can’t make schedules for the whole year!” In German warehouses Amazon was using past market data and statistics to make more long-term planning possible – and so, the Polish management’s lie was made visible. Incidentally, workers in FC2 don’t get their schedules for the next week until one day in advance.

Through offering this report, we hope we can contribute to this kind of exchange among workers. We hope this information can help to break the separation of workers across national and regional borders, and the divide and rule strategy by which management governs. In order to follow this path, there is much more to do. For example more exchange between other Chinese warehouse workers would be helpful to see how the working conditions differ between JD, Alibaba-related warehouses and Amazon, or looking into the conditions of transportation and delivery workers who provide logistics for these warehouses.

—Inbound/Outbound Notes, April 2017

Notes

[1] On the struggles and cross-border networking among Amazon workers in Europe and, to a smaller degree, India, see:

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2016/03/amazon-poland-poznan-strikes-workers/

http://en.labournet.tv/video/6925/amazon-workers-meeting-poznan

https://angryworkersworld.wordpress.com/2015/11/06/open-letter-to-iww-comrades-regarding-amazon/

[2] https://www.digitalcommerce360.com/2016/01/27/chinas-online-retail-sales-grow-third-589-billion-2015/

[3] http://www.mckinsey.com/industries/retail/our-insights/amazon-chinas-president-on-transformative-technologies

[4] http://seekingalpha.com/article/3960629-jd-com-dominating-rapidly-growing-chinese-online-retail-market

[5] https://www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2015-09-10/amazon-struggles-with-china-market-a-case-study

[6] http://www.cnbc.com/2017/01/18/jack-ma-difference-between-alibaba-and-amazon.html

[7] https://qz.com/899922/once-poverty-stricken-chinas-taobao-villages-have-found-a-lifeline-making-trinkets-for-the-internet/

[8] http://www.cnbc.com/2015/01/28/china-agency-slams-alibaba-for-fakes.html

[9] http://www.ecns.cn/cns-wire/2016/09-20/227133.shtml

[10] http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/tech/2016-09/21/content_26847915.htm

[11] http://www.reuters.com/article/us-bulgaria-economy-alibaba-idUSKBN14V226

[12] http://www.mwpvl.com/html/amazon_com.html

[13] We decided not to disclose the name of the city and the location of the warehouse.

[14] It was the introduction of such a “flexible scheduling system” that led retail workers in several Walmart stores throughout China to strike last summer: “With the new flexible scheduling system—allowed under China’s labor law, but only approved by the labor bureau for highly seasonal businesses—Walmart is in the process of replacing the existing eight-hour day for full-time workers. Store managers will be permitted to allocate workers any number of hours per day or per week, as long as each worker’s total adds up to 174 hours per month.” See “In China, Walmart Retail Workers Walk Out over Unfair Scheduling” by Kevin Lin, http://labornotes.org/2016/07/china-walmart-retail-workers-walk-out-over-unfair-scheduling.

[15] China’s Social Insurance system includes five programs (the Pension System, Medical Insurance, Unemployment Insurance, Work-Related Injury Insurance and Maternity Insurance) that are funded by contributions from both employer and employee. For details, see “China’s Social Insurance System,” http://www.clb.org.hk/content/china%E2%80%99s-social-security-system .

[16] He said the amount of orders had decreased in 2015-2016, so FC2 had stopped hiring and several dozen workers had left. After FC2 started processing orders for the online platform Yunji in mid-2016, the amount of work had returned to its earlier level, but few new workers were hired, so the pace of work increased.