Overview: Class Wars

The ascent of the mainland in international production chains was, however, only made possible because of rapid and far-reaching changes to the decaying class structure left behind by the developmental regime. In this section we detail the formation of both the top and bottom of a capitalist class system in mainland China. The decades covered here are the final years of the transition, marked by rapid expansion of the market, rapid financial restructuring, the conversion of state-owned enterprises into multinational conglomerates, and the final destruction of the socialist-era industrial belt in the Northeast. By the early years of the new millennium, China had completed its transition to capitalism.

The process of transition is a contingent one, with subsumption into the capitalist economy taking a markedly different character in different regions at different times. One feature of the Chinese case, explored throughout, has been the wholesale exaptation of certain mechanisms from the developmental regime in order to stabilize the transition, ensuring conditions necessary for the accumulation of value. In the transition to capitalism, novel adaptations are of course important, with the commodity form, the wage and the specifically capitalist role of money all playing such a role. But equally important are features that originate from previous modes of production, adapted to serve the needs of accumulation. As suggested above, this extends to the market itself, with pre-capitalist commercial networks exapted into the capitalist world in both Europe and Asia.

Another case more specific to China that we have emphasized here and elsewhere is the hukou system. Whereas its function in the socialist era was to secure the urban-rural divide by freezing population movement, the process of transition gave the hukou an opposite function: facilitating migration while also generating a dual labor market in the cities, thereby helping to suppress both wages and unrest. The early proletariat was a product of the collapse of the rural economy, and for many years, full inclusion into this emerging class was largely a matter of one’s rural hukou status. But even after proletarian conditions generalized, hukou remains to this day an important dimension of state control, helping to maintain accumulation overall.

A similar process of exaptation helped to form the top of the class hierarchy, as technical and political elites within the developmental regime’s bureaucracy fused. This fusion positioned these elites such that they became the main beneficiaries of the privatization taking place in the nineties and into the new millennium, which would transform this provisional ruling stratum of “red engineers” into a properly capitalist class. In this way, the administrative capacities of the bureaucracy would be exapted, transforming the party into a managerial body of the bourgeoisie.

But these processes were not without conflict. The transformation of the ruling class and the birth of the proletariat took place through a sequence of struggles in the final decade of transition. The first of these was the Tiananmen Square movement in 1989, which would ultimately set the terms of continuing reforms—ensuring that they would both exclude the interests of the old industrial working class and be defined by a process of marketization helmed by the existing party, rather than some new political organ. The crushing of the unrest ensured the stability necessary to attract new rounds of investment throughout the subsequent decade, and to engage in a wide-ranging process of financial reform, remodeling the banking system and capital markets in mimicry of the high-income countries.

We open Part IV with an analysis of Tiananmen, then, as the event that secured the position of the new ruling class and made possible the following decade of reform. The second major struggle in this period was the gutting of the developmental regime’s industrial heartland in the Northeast at the turn of the century. This process was defined by mass privatization, layoffs, and protests. The end result was the disintegration of the final remnants of the developmental regime’s class system, and the completion of the transition to capitalism. We therefore close with the defeat of these protests and the creation of the Northeastern rustbelt.

Tiananmen Square and the March into the Institutions

By the mid-1980s, a small but increasing number of urbanites had broken out of the iron rice bowl of the danwei (state work unit) system, with its guaranteed employment and state grain rations, jumping into new opportunities created by an expanding urban consumer market. Small business was encouraged by the state to fulfill increasing demand. Shops opened up all over Beijing, for example, selling cheap goods usually produced by the TVE (township and village enterprise) sector and/or by new migrant labor, such as workers from Wenzhou who produced popular leather jackets in small, family-run businesses in Beijing’s Zhejiang Village. In Haidian, Beijing’s university district in the northwest of the city, the morning brought a train of peasants on donkey-drawn carts carrying produce to sell on the open market. Street vendors also proliferated, creating a much more vibrant nightlife in the city. Families started privately run restaurants by breaking holes in the walls separating the sidewalk from small danwei buildings. Customers stepped through the hole in the wall into a restaurant that focused on serving good food marketed to changing urban tastes, markedly different from the bland taste of state-run restaurants with terrible service.

This was the point at which marketization could clearly be seen to be transforming the fundamental spaces that composed the socialist-era city. Markets bustling, new migrants settling and the literal opening of the autarkic danwei walls all seemed to symbolize a new era of free movement. On one level, this echoed traditional patterns of urban development on the East Asian mainland, such as the shift from the ward system of the Tang dynasty to the open cities of the Song. Such cities had always been marked by a tension between cloistering and openness. At the same time, the space began to mirror new structures of power and inequality that were only just emerging. The slow trickle of escapees from the danwei system created an emergent class of urban entrepreneurs (known as getihu), who could be seen travelling the city on motorcycles and even in private cars. Meanwhile, peasants entered urban spaces more regularly, both as small-scale produce vendors and as new migrant workers. This broke down one of the fundamental spatial divides that had existed in the socialist era, beginning the transformation of the hukou system from a method for sealing the cities off from the countryside to a method of segmentation used to enforce labor discipline on a new proletariat. The spaces inhabited by peasants in the city made clear that they didn’t enter on equal terms: the informal character of the street vendors’ carts and the ramshackle quality of new migrant settlements signaled this, and began to stoke fears among urbanites of the possibility of growing urban slums—something rendered in the official literature as a risk of “Latin Americanization.”

For the vast majority of urban workers, who were still dependent on the danwei system, living standards improved only slowly. Meanwhile, the changes led to shifting class formations and alliances that destabilized the urban political scene. Stories and complaints about corruption proliferated. The foreign cars that appeared on the streets, passing urbanites riding slowly to work on buses and bikes, became a particular object of scorn, and stories spread rapidly about leaders driving around the city in Mercedes. Discontent was at first largely held in check by a combination of state repression and improved living standards. But as price reforms and high inflation (especially on food) began to cut into incomes from the mid-1980s, it became increasingly difficult for the state to keep criticism of the party from turning into open protest. When inflation first began to spike in 1985 and 1986, students began a series of protests for political reforms and against corruption. These protests spread from Anhui Province, where they began in early December of 1986, to 17 major cities around China, including Beijing. Yet the protests failed to gain support outside of universities (the largest protests occurred in Shanghai and Beijing, and yet even there only about 30,000 students participated in each) and were quickly suppressed.[1] Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang, seen by other CCP leaders including Deng Xiaoping as too lenient on the movement, resigned a few weeks later in mid-January 1987.

As the old danwei system continued to strain under the reforms, however, dissatisfaction among urbanites erupted into the largest reform-era protests in the spring of 1989, with the participation of up to two million people in Beijing at the peak of the movement in May. This time urban workers joined a stage initially set by student protestors, but the alliance was temporary at best. While there was a diversity of opinions among both groups, interests generally pushed students in one direction and workers in another. As the politics rapidly unfolded, individuals were caught up in a movement that none really controlled. Students—representing a rising class of entrepreneurs and managers in the expanding market economy—were mostly critical of the way that the reforms were being implemented. Workers were more directly critical of the content of the reforms. Following the repression of the movement in June of 1989, students would never again unite with workers in the old socialist industries. The educated class of managers became key beneficiaries of the reforms, while workers lost out, left to protest sporadically and alone, until the remnants of the socialist-era working class were finally extinguished in a wave of deindustrialization at the turn of the century.

At the same time, the weakening of state control over university campuses created a new space for political debate, even as the state added ideological education in the aftermath of the 1986 protests. Students looked for the deep causes behind China’s turbulent political past, especially the Cultural Revolution. Turning to existentialism, liberalism and neo-authoritarian ideas, students tended to argue that Chinese culture itself was to blame for political repression, arbitrary bureaucratic power over daily life, corruption and party factionalism. A new May Fourth movement was necessary, and it had to be led by intellectuals.[2] Ironically, neo-authoritarianism was one of the most popular ideologies among students.[3] Its basic idea was that a single strong leader in the CCP needed to take control of the party to stop the factional fighting and bureaucratic stasis that was holding up the progress of reform. That leader should take advice from intellectuals, who supposedly knew how to reform society. There were also liberal critics of authoritarianism among the students, along with a smaller group who were critical of the direction of the reforms for damaging the living standards of ordinary citizens. For all the vague talk about “freedom” and “democracy” at the time, however, most students seemed enamored with the idea that they alone understood how to solve China’s problems.[4]

When Hu Yaobang died on April 15th, 1989, students immediately began to write posters on campuses and hold discussions. Hu was especially popular among students and intellectuals, as he was tasked with rehabilitating intellectuals and rebuilding the party’s relationship with them at the beginning of the reforms. Seen as incorruptible, Hu was a symbol of correct leadership within the party sidelined by hardline bureaucrats protecting their privileges. Small student groups, especially those with good connections within the party, left wreaths commemorating Hu on the Monument to the People’s Heroes at the center of Tiananmen Square (as urban residents had done for Premier Zhou Enlai following his death in 1976, leading to the April Fifth Movement). The first student protest was a nighttime march of around 10,000 to the square from the university district on April 17th. At the lead, students carried a banner that proclaimed themselves to be the “soul of China”—an elitist formulation that would characterize their politics for the next two months. The monument at the center of the square soon filled up with wreaths left for Hu, and in the first days it became a site where anyone could jump up on the first ledge of the monument to give a speech to hundreds of onlookers. At night, protesters often gathered at the gate of Zhongnanhai, the main compound in which top CCP leaders lived.

Students and intellectuals, however, were quickly joined by young workers and unemployed urbanites, most importantly by forming the Beijing Autonomous Workers’ Federation (北京工人自治联合会).[5] Yet these two social groups did not come together to form a coherent social movement even as they took part in the same events. Momentarily brought together by their shared opposition to corruption in the party, which had been worsened by market reforms, the two groups were divided by much more than what unified them. In terms of protest styles, students claimed exclusive ownership over the movement, in fear that they could not control other groups, who might use violence or provide the state with an excuse for repression. They tried to keep others out of the protests or, failing that, to sideline other groups as mere supporters and not full participants. As students and intellectuals believed that they were the only ones truly able to “save China,” they often blamed “peasants” for leading the country astray during the revolution and the socialist era. In the early days, students set up a coordinating organization in an attempt to control the movement, the Autonomous Student Union of Beijing Universities (北京高校学生自治会) with an elected leadership. The student union organized a widespread boycott of university classes beginning on April 24th. As the protests developed, other student organizations formed and competed for control. The independent Beijing University Student Dialogue Representatives Group (北京高校学生对话代表团) attempted to discuss demands with party leaders, discussions broken up by other students. The occupation of Tiananmen Square was controlled by the Headquarters for Defending the Square (保卫天安门广场总指挥部), yet another independent student organization. The Headquarters’ leadership was elected by those occupying the square, and the main power it enjoyed was control over a loudspeaker system at the center of the protest. Further, students cordoned off the center of the square around the Monument to the People’s Heroes with a hierarchical series of concentric circles. To get into the outer rings of the circles, one had to be a student, deeper towards the center required you to be a student leader with some connection to the Headquarters. The students forced the workers’ organization to set up its tents across the street from the square itself.

Students also had a very different relationship to the reforms compared with workers. Students largely wanted the reforms to move faster, to be better organized and more efficient. They were afraid that corruption was leading to a weakening of the reforms. By the mid-1980s, however, workers had begun to see their interests being undermined. There was new unemployment (as state enterprises, now responsible for profits and losses, were given the right to lay off some workers), stagnating wages, and, most importantly, high inflation, reaching levels of hyperinflation by the end of 1988. For workers, the reforms had to be slowed down or significantly rethought. Price stabilization in particular was crucial, since workers were in the process of losing their guarantee to cheap, state-subsidized grain. While students at first focused largely on mourning the pro-intellectual Premier Hu Yaobang, the workers’ criticism of the party and its reformist policies were more broadly political than those of students early on in the movement. For the workers, corruption was seen as a problem not because it was weakening the reforms, but instead because it indicated the emergence of a new form of class inequality. In handbills, workers asked how much Deng Xiaoping’s son lost in bets at the Hong Kong racetracks, whether Zhao Ziyang paid for playing golf, and how many villas the leaders maintained. They further questioned how much international debt China was taking on in the reform process.

The students and workers also had very different ideas about democracy. Students spoke vaguely about democracy, but often called for intellectuals to have a special relationship to the party. Most were more interested in having Zhao become a more powerful, enlightened leader for whom intellectuals could play the role of advisers, showing him how a market economy should really work. When one talked with workers, they had a much more concrete idea of democracy, one that had emerged over a long period of worker struggles in China, clearly visible, for example, in the strikes of 1956-1957, the Cultural Revolution, and the 1970s.[6] For many workers, democracy entailed workers’ power within the enterprises at which they worked. Workers complained about the policy of “one man rule” in work units, wherein a factory director was a virtual “dictator.”[7]

The students, unlike the workers, were intimately involved in the factional fights going on within the CCP. Students largely took the side of the more radical market reformer, Zhao Ziyang, who headed the party at the time. Zhao wanted to push the reforms through more quickly. On the other hand, the students largely reviled Li Peng, the head of state, well before he became the figurehead of martial law in late May. A moderate reformer, Li was seen as an old style bureaucrat who stood in the way of a rapid and efficient transition to a rational market economy. Workers did not really take part in this factional fight. They’d gained little by participating in factional fights before, specifically during the Cultural Revolution and the Democracy Wall movement of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The workers’ federation warned that “Deng Xiaoping used the April 5th movement [of 1976] to become leader of the Party, but after that he exposed himself as a tyrant.”[8] Party members returned the favor in kind, with the All-China Federation of Trade Unions publicly backing the students but ignoring the workers who participated and their fledgling organization.[9] Party elders, however, shifted away from supporting General Secretary Zhao’s policy of concessions to the students as May developed. At a contentious May 17th meeting of the Standing Committee of the Politburo held at Deng Xiaoping’s residence, Deng and Li Peng criticized Zhao’s approach, claiming he was splitting the party. Deng pushed for the declaration of martial law, which was formally announced on May 20th. In the early morning of May 19th, Zhao went to the square to warn students to leave, saying they should not sacrifice themselves for a movement that was over. Then Zhao left the square, having lost his position within the party, and was soon put under house arrest for the rest of his life. The late May announcement of martial law sharpened the politics of participants, with the workers’ federation announcing that “‘the servants of the people’ [the party] swallow all the surplus value produced by the people’s blood and sweat,” and that “there are only two classes: the rulers and the ruled.”[10] The majority of students, conversely, still held out for support from Zhao’s faction even after martial law was declared. A potential alliance between students and workers never materialized under the pressure of the rapidly changing political context.

Students initially told workers not to strike so the movement’s focus would remain on themselves and their power within it could be retained. After martial law had been declared on May 20th, however, students finally saw the importance of worker participation, though again only in a supporting role, and they finally asked workers to undertake a general strike. By that point, however, participation in the protests had dropped dramatically, and it was too late for workers to fully mobilize their forces. Nonetheless, workers were still able to pull large numbers to resist the implementation of martial law. In fact, workers continued to put more people into the streets even as student numbers dwindled. But by this point, the party had marshaled up to 250,000 soldiers in the outskirts of the city. Workers and other urban residents were initially able to stop the entry of soldiers into the city from the night of June 2nd into the 3rd, blocking roads and surrounding troops in vehicles. This led to only a small amount of violence, with urbanites often feeding the tired soldiers caught up in the crowds for several hours before they gave up and pulled out of the city center. This only encouraged more resistance the following night.

From the night of June 3rd into the 4th, however, the army moved more resolutely towards the square to put an end to the protests. That night it was mainly workers and unemployed youth who attempted to slow the approach of the army in the streets leading up to the square, and many of them paid for it with their lives, with hundreds of civilian deaths (among whom very few were students). Along Chang’anjie—the main east-west avenue bisecting the city at Tiananmen—workers and other Beijing residents built blockades with buses, often setting them afire. Molotov cocktails and rocks were thrown as soldiers approached. The intersection around Muxidi on Chang’anjie to the west of the square was particularly hard hit, with pitched battles between workers and soldiers. Many deaths were concentrated there. As the first soldiers in armored personal carriers (APC) arrived on the square, some students and residents continued to resist, and an APC was set on fire. Several civilians were killed on the edges of the square. Once the main body of the army reached the square they stopped, and by the early morning they were negotiating with the remaining student occupiers, allowing them to leave the square and walk back to their campuses—though not without several being beaten by soldiers first. The protests in the capital were over, but the repression continued. Workers were hit the hardest in terms of prison sentences and executions in the days and weeks that followed, with student participants getting more lenient sentences.

The harsh crackdown on worker participants became a condition for the acceleration of market reforms in the 1990s, most notably the liberalization of the food market in the early 1990s, which the workers clearly would have otherwise continued to resist. As the Chinese economy became increasingly integrated into global capitalism after 1989, the economic interests of students and workers diverged further. The students of the 1980s became the middle and entrepreneurial strata of the 1990s, benefiting from the continuation of the market reforms that the crackdown on the protests enabled.[11] In the late 1990s, workers in many older state-owned enterprises were laid off, rural-to-urban migration increased rapidly, and a class of “new workers” came into being, making low wages and living a precarious existence within the global manufacturing system. As worker and peasant protests increased again from the mid-1990s, they were not joined by students or intellectuals, who had mostly moved to the right when they still had any politics at all, arguing for the protection of property rights and free speech or increasingly taking nationalist positions.

Bureaucracy to Bourgeoisie

The events in Tiananmen were, in retrospect, a key moment in the formation of a domestic capitalist class out of the ruins of the socialist era bureaucracy. The protests and their crushing set the terms for this process in a number of ways. First, it became evident that there was a new, highly-educated faction of urbanites who now sought incorporation into this ruling class, and were, moreover, prone to push for accelerated reforms, expansive privatization, and various new state structures that (they imagined) would best accommodate the operations of a market economy. In this way, the position of students in ’89 would prefigure the position of purely private capitalists who gained their wealth with little help from the state and today remain un- or under-incorporated into the existing party patronage structure.[12] At the same time, the students themselves demonstrated the importance of incorporating new intellectuals (and the new-rich more broadly) into the party, from whence they could also begin to accrue capital in the market economy.

Second, the crushing of the Tiananmen movement also made clear that the nucleus of a new capitalist class would largely be incubated within the party itself. Of course, there were (and still are) a large number of private capitalists who stand entirely outside the party, and throughout the 1980s it seemed to be an open question how much power and political leverage would be allowed newly-rich mainlanders or old capitalist families returning from Hong Kong or overseas. But the events of ’89 made clear the limits of this leverage. There could be no tolerance for reforms that outpaced party control—even if basically all the economic policies advocated by the student groups would eventually be implemented. Meanwhile, the party itself was opened even more to intellectuals and the newly rich. With socialist era class designations officially abolished in 1978, the total numbers of cadre continued to grow and new members would come from increasingly better educated backgrounds. This process was in many ways continuous with trends in the growth of bureaucratic privileges that had long plagued the socialist era. More importantly: the ability to draw from a well-organized, ready-made ruling class exapted from the tops of the tumultuous class structure of the late developmental regime gave the entire process of transition a much more stable, systematic character than that seen elsewhere—particularly for a country lacking the direct military patronage and geopolitical oversight of the reigning hegemon, which had ensured relative stability during industrialization in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan.

We will explore the current character and composition of the Chinese ruling class elsewhere—in the final part of this economic history, as well as in other articles, interviews and translations—but in order to understand the nature of the transition, it’s essential to trace out the precursors to the development of a capitalist class on the mainland, gestated within the party bureaucracy inherited from the developmental regime. This was a process marked by apparent continuity, but also defined by important internal changes to the structure and priorities of the party itself. The crushing of unrest that defined the “short” (’66-’69) cultural revolution gave way to the “long” (’66-’76) cultural revolution, during the latter two thirds of which any potential popular movements had been essentially defeated, but factional conflicts within the upper ranks of the party existed in an uneasy détente—exacerbated by the ossification of the developmental regime, the growing power of the bureaucracy and the direct militarization of production. This détente saw a continual increase in the absolute number of cadres, alongside the maintenance of the power and privileges of those at the top. But the period also saw a number of reforms that, on the one hand, seemed to arise from the recognition that the system was ossifying and needed to be modified, and, on the other, acted as pragmatic tools to stifle the power of particular factions. In order to serve both functions, recruitment was prioritized among those with lower education, and state investment was redirected. The clearest symbol of this process was the closure of universities, the rustification of the highly-educated children of high-ranking officials, and the expansion of primary education, particularly in the countryside. In addition, there were several high-profile promotions, placing figures like Chen Yonggui (a nearly-illiterate peasant leader from the model village Dazhai) into some of the highest positions within the party.

It is not at all unusual for the earliest members of a country’s capitalist class to emerge from the upper echelon of the increasingly archaic class structure that precedes the transition. In some cases, this process took the shape of a forcible subsumption into the global economy imposed by European powers on conquered peoples—where it was common for the colonial apparatus to selectively delegate power to a subset of pre-existing local leaders willing to capitulate to the colonial state, giving the new class structure an appearance of continuity with “indigenous” systems of power. But even outside the colonies, the same phenomenon has been a feature of almost every instance of capitalist transition. This includes the textbook case of England, where the early enclosures that led to enhanced agricultural productivity and the rapid growth of the industrial economy were in fact instigated by landowners already empowered by the aristocracy.[13] The continuity is equally apparent in the first few “late” developers, such as Germany and Japan, where the role of feudal landowners combined with a pre-existing state bureaucracy to facilitate the transition in a way that retained the power of various pre-capitalist ruling classes—but also effectively transformed them into capitalists, or at the very least landlords and rentiers in the sense described by Marx.[14]

None of this implies that such classes had somehow already been capitalist, nor that the state bureaucracy inherited by the Germans or Japanese was in some sense “state capitalist” prior to marketization. The absurdity here is self-evident: just because various feudal, tributary or other indigenous modes of production gave way to capitalism, and many families within old ruling classes retained their power throughout, does not mean that these pre-capitalist systems were actually already capitalist, even if they had been shaped indirectly by competition with the early capitalist powers. But exactly this sort of argument is often made for China. Since so many within the party-state bureaucracy would retain power and effectively bequeath it to their children, it is assumed that there must have been some secret capitalist kernel within the bureaucracy all along, ultimately unleashed by an artful combination of tragedy and betrayal.

Not only is the chain of logic here backwards, there is also an analytic error in conflating class and power. Just because power might span modes of production—embodied in the same families, the same locales, and even in a state that takes the same name—the class relations that generate that power nonetheless undergo a change. Class is not a simple designator for those who have authority and those who don’t, nor is it a sociological tool for cutting a population into brackets of income or education. Class is an immanent polarity generated by the social character of production. It is an emergent property of the way that things are made and basic human needs are met within a given mode of production. Constantly maintained and continually reproduced by this process, the power of a ruling class is largely power over the means of production and the force guaranteeing that production continue, but it is rarely a power over the nature of the mode of production itself. In this sense, not even those at the top of a system can simply choose to change it, as their position is constrained by inertial dynamics largely out of their control.[15] This is particularly true for capitalism, where class emanates continuously from the circuit of capital.

Class conflict, therefore, does not simply designate the tug-of-war between two interest groups but instead a more fundamental conflict over class itself: when the circuit of accumulation begins to break down, the fundamental interest of the bourgeoisie is to restore it by whatever means necessary, while the drive of what used to be called a “class conscious” proletariat is the continual rupture of the circuit, which opens the potential of the proletariat’s self-abolition as a class via revolution. This is an important distinction, because it makes clear that mass movements can still be mobilized in the service of restoring accumulation, even if they have the appearance of class conflict. In fact, the class power of the bourgeoisie requires the participation of the proletariat at almost every stage of its deployment. The defining activity of the bourgeoisie as a class (aside from its everyday compositional activity, as the owners of capital and those who siphon surplus value from the work of the vast majority) is the perpetual maintenance of the material community of capital. It is in this sense that the Chinese Communist Party ultimately became a party of capital, acting as both the attendants of original accumulation and the intra-class managerial organ for the domestic bourgeoisie.

Since class is not static, but instead an emergent process, we can only understand the growth of a capitalist class system in China via its relation to the changing nature of production. Even the many reforms that brought intellectuals and, later, businesspeople into the party could not have secured the existence of a capitalist class without the simultaneous creation of its opposite, mutually-dependent pole: the proletariat. Accounts that overemphasize the early stages of ruling class formation, then, tend to place these internal reforms at the center of the narrative. While it’s true that a heightened concentration of power in the bureaucratic class (combined with the political purging of lower-born leaders starting with the 1976 arrest of the Gang of Four) certainly helped to facilitate the smooth creation of a capitalist class, the mere shifting and concentrating of power within a bureaucracy does not make a bourgeoisie. In reality, such reforms were simply important precursors, which could only be completed alongside the emergence of commodity relations, the proletarianization of the vast majority of the population, and the existence of widespread exposure to the global economy.

The period that we review here is largely the era of such precursors, rather than the era in which a clearly and fully capitalist class would wield full power. This means that factional conflicts continued within the bureaucracy throughout, often helping to facilitate the cyclical process of reform and retrenchment that marked the period. But the process of composing a new capitalist class is highly contingent, and even though the transition is neither caused nor completed by the “betrayal” of the pre-capitalist ruling class, the local character of this class-in-formation can wield a disproportionate influence on the trajectory of the transition itself. Comparing the collapse of the Soviet Union and the subsumption of the Chinese developmental regime should be clear enough evidence of this fact. In the Chinese case, the new ruling class developed its initial form as an alliance, and then fusion, of political and technical elites who had ascended to power somewhat separately within the turbulent class structure of the developmental regime. Before it was a bourgeoisie, then, the capitalist class took its preliminary form as a class of “red engineers” who had ascended to power through the party machinery, giving them a vested interested in ensuring the stability of the party itself. It was this stability that allowed the party to nurse the growth of a new bourgeoisie.[16]

The back and forth of educational reforms were key to this process, but the categories used can often be misleading. Much of the discussion of violence in the Cultural Revolution, for instance, emphasizes attacks on “intellectuals,” or those whose families had “counterrevolutionary” class backgrounds. The turn to reforms, meanwhile, saw the abolition of these official designations (which had de facto become inherited), and a move to re-open universities, offer party membership to previously banned groups, and to return rusticated youth to the city (and often to the newly reopened colleges). In the narrative that sees the reforms as initiated by an act of betrayal, this seems to be a shift whereby those formerly designated “counterrevolutionary” were now regaining power—as if the transition were purely a backward slippage, led by the same forces that had helmed the first, stalled transition in the Republican era. But this is hardly the case. Many of those who held bad class backgrounds under the developmental regime had, by this point, inherited those designations from parents who had little or no way to transmit pre-revolutionary class privileges, the most important of which would of course be intergenerational wealth transfer. This is precisely why the question of education became so central to debates on class power within the late developmental regime.

But even the category of “intellectual” is deceptive. In its current connotation in English, this term seems to imply a certain academic or artistic faction of elites, maybe at most stretching to include the work of think tanks, policy planners and others who act within the political sphere or in an advisory capacity. Today, the term only barely covers the roles played by engineers or others with high-level technical knowledge. Nonetheless, given the educational emphasis of the developmental regime, those with such technical knowledge composed a large fraction of the “intellectuals” who sat at the center of the debates on education policy. And there is no ambiguity to which side those debates ultimately fell: While as late as 1985 “the bulk of party members were still from the poorly educated classes” the composition was changing rapidly, with “new members categorized as intellectuals [growing] from 8 percent in 1979 to 50 percent by 1985.”[17] But this was by no means a new generation of the old, pre-capitalist class of classical intellectuals. Instead, “the heart of the New Class was made up of Red [i.e. those with political power] and expert cadres who had been trained at Tsinghua and other universities during the Communist era.”[18] The same period saw mass retirements from the party, particularly among the now-elderly members who had joined before or just after the revolution—many of them poorly educated peasants or workers at the time—shifting the balance in favor of these newer members.[19]

The influx of “intellectuals” into the party was in reality the influx of those with high-level technical training and pre-existing political influence (often the children of those who had held privileged positions within the developmental regime). On top of this, many had experienced a certain degree of hardship during the Cultural Revolution, such as rustication or attacks on their families—though notably not the massacres, military crackdowns and long prison sentences meted out to radical workers. Though later the educational focus of these new elites would diversify somewhat, in the early years science and engineering dominated. The trend was made evident as these elites graduated into the highest-level positions within the party: “The proportion of the party’s ruling Political Bureau that was made up of individuals with science and engineering degrees had grown dramatically, increasing from none in 1982 to 50 percent in 1987, 75 percent in 1998, and 76 percent in 2002.”[20] During the Sixteenth Party Congress in 2002, “all nine members of the Political Bureau’s Standing Committee, the most powerful men in the country, had been trained as engineers, and four, including Hu [Jintao], were Tsinghua alumni.”[21] Only the last two decades have seen the educational composition of the capitalist class in China begin to shift more toward the global norm—precisely when the bottom of the class structure would take full form through mass privatizations, allowing this precursor class of red engineers to phase into a properly capitalist class.

Prior to this point, however, the preliminary nature of this new class also meant that privileges still accorded much more readily to those with political connections and technical skill than to those who directly controlled production. When large-scale privatization did occur, it was not coincidental that the managers of successful state-owned enterprises and the local and provincial officials in league with them were largely drawn from this class-in-formation. Privatization would entail that “most state-owned and collective enterprises became the property of their managers,” completing the formal transition of power from mere political privilege into direct ownership of the means of production.[22] This also meant that the wealth of such elites was now linked much more directly into the circuit of value production, creating a mutual (albeit uneven and exploitative) dependency of the ruling class and the proletariat.

Nonetheless, the heritage of the “red engineers” would carry a certain inertia. The patronage system established within the party soon proved an efficient way to mobilize capital and prevent destabilizing factional conflicts among members of the ruling class. The disciplinary mechanisms of the developmental regime state, overseen by “red” bureaucrats, would also become useful in establishing and preserving the conditions necessary for continued accumulation. Maybe most directly: the important role that would be accorded to the newly marketized SOEs (transformed into global conglomerates) increased the power of high-level managers and others who had climbed the ladder of industrial engineering in the transition era, producing some of the wealthiest capitalists helming some of the most powerful corporations in the world today. Altogether, this inertia would ultimately result in the divide between these capitalists “inside the establishment” (体制内) and those “outside,” foreshadowing greater conflicts to come.

The Resurrection of the South

The ten years stretching from the early 1990s to the dawn of the new millennium was the period in which China’s domestic economy would begin to be fully and directly integrated within the global capitalist market, no longer insulated by the “air locks” imposed on currency and commodity trade throughout the previous decade.[23] The 1990s would also see the coastal character of China’s new industrial structure take full form, establishing a new geographic divide that both traversed and sharpened the socialist-era inequality between urban and rural. Coastal development and global integration began with a new wave of foreign direct investment following the state’s successful containment of the urban crisis of 1989, which had been marked by rapid inflation and widespread social unrest. When the uprisings in Beijing and elsewhere were crushed and inflation brought down through a period of economic retrenchment, the Chinese state proved its stability, in sharp contrast to the rising tide of popular uprisings throughout the socialist bloc. Even while Western governments sought a series of sanctions in the wake of the widely publicized Tiananmen Square Incident, capital had already begun to pour in from the bamboo network.

A strong signal was given to foreign investors by Deng Xiaoping’s 1992 “Southern Tour” (南巡), which was both a symbolic statement of the administration’s commitment to continued reform and an announcement that a wide array of new sectors, including real estate, would be open to foreign investment. Particularly important in terms of global market integration was a new policy allowing foreign-funded manufacturers the opportunity to sell on the rapidly growing domestic market in exchange for investment. This package of reform policies was ratified at the Fourteenth Party Congress in October 1992, the first time that the party’s highest echelon formally endorsed China’s adoption of a “socialist market economy.”[24] The shift in rhetoric justified renewed support for domestic market forces on multiple fronts: cutting back the remnants of central planning even further, extending market pricing to the majority of the economy, instituting a new tax system that treated private ownership more equitably, and giving state-owned firms far more ability to lay off workers. At the same time, the shift symbolized the end of the conservative retrenchment with regard to foreign investment. Private domestic enterprises were allowed to engage in joint ventures with foreign firms, the Shenzhen and Shanghai stock exchanges (founded and re-opened, respectively, a few years prior) now allowed foreigners to purchase a limited number of shares for the first time, the dual exchange rate was abolished in favor of a unified (heavily regulated) market rate in 1994.[25] All of this opened the door to the fundamental restructuring that would occur throughout the decade, effectively liquidating the old socialist-era class of urban grain-consuming industrial workers.[26]

Export growth had already ensured that China was running a large and growing trade surplus, which helped to dampen the fear of running into the sort of payment problems that had plagued the era of oil-backed trade. Secured by this surplus, reforms where followed by a flood of foreign investment into the new coastal hubs. By 1993, FDI reached $25 billion, which was “almost 20% of domestic fixed investment,” and in the same year foreign-invested firms’ share of domestic industrial production “may have surpassed 10%.”[27] Though the continuing role played by the Chinese state would draw comparisons between the “Chinese Miracle” and its predecessors in Taiwan, South Korea and Japan, this period of rapid growth was far more dependent on foreign investment and far less driven by large state-owned (or simply well-connected) monopolies than in any of the other “miracle” economies. In 1991, with incoming FDI at slightly more than 1 percent of its GDP, China had already matched or surpassed the FDI-to-GDP ratio reached by Japan, South Korea and Taiwan during either their industrial booms or their later periods of internationalization. By 1992, the share had increased to over 2 percent, and by 1994 it reached a staggering 6 percent, making the Chinese boom much more comparable to the similar export-driven growth waves experienced in Southeast Asia, “where inflows around 4%-6% of GDP have been common.”[28] But even this is an understatement, since China’s less developed interior acts as a statistical damper when such figures are averaged for the country as a whole. In Guangdong and Fujian provinces—both comparable in population and land area with most countries in Southeast Asia—the period from 1993 to 2003 would see an average annual FDI to provincial GDP share of 13 and 11 percent, respectively.[29]

The new geography of production was pronounced: between 1994 and 1998, the Southeast Region as a whole (Guangdong, Fujian and Hainan) contributed some 46 percent of all China’s exports, trailed by the Lower Yangtze (Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang) at 21 percent and the socialist-era industrial hub in the Northeast at 23 percent. All other provinces contributed a mere ten percent.[30] This imbalance was not coincidental. On the one hand, it marked the ascendance of seaborne trade and coastal logistics hubs. On the other, it was also a relic of much older, pre-capitalist market networks that dated back to the Ming and Qing dynasties, now revived in the form of the bamboo network. Guangdong and Fujian were the two major home provinces of most overseas Chinese families—and even those who had lived in Southeast Asia for decades often retained some level of linguistic, familial or at least cultural ties to these locations. In many cases, these connections were quite direct, with recent out-migrants in Hong Kong and Taiwan seeking to reconnect with relatives who had remained on the mainland after the revolution. In Dongguan, for instance, residents “had at least 650,000 relatives in Hong Kong and Macao” in 1986, “and another 180,000 (huaqiao) in other foreign countries, mostly North America.” As many as “half of the contracts [local cadres] had signed were with former Dongguan residents now living in Hong Kong.” [31] But even overseas Chinese who had lived several generations in other countries were given extremely favorable terms of investment by the Chinese state, and capital from the bamboo network was frequently treated as if it were domestically sourced. The early ascent of the Pearl River Delta and, to a lesser extent, places like Xiamen in Fujian, were therefore direct results of these global connections. Once these areas had been industrialized, they exerted a massive gravity for both labor and investment, securing their position even as new sources of FDI began to flood into the country over the course of the 1990s.

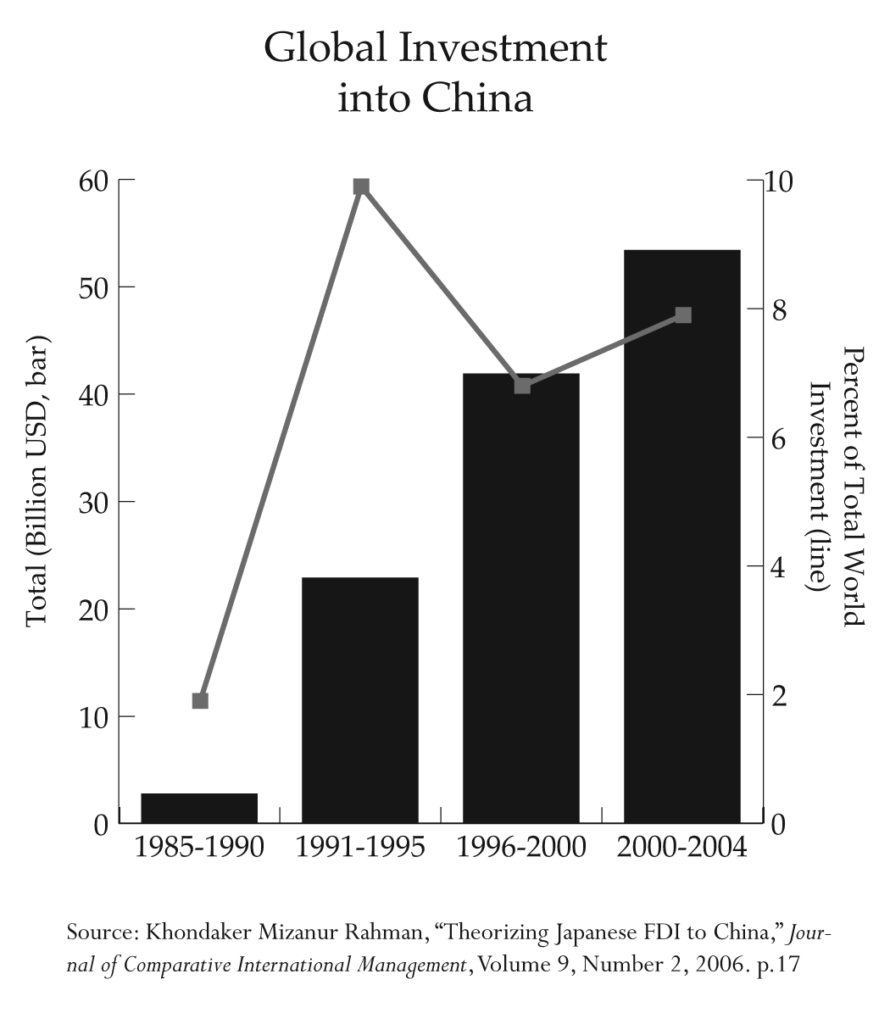

Though Hong Kong and Macao remained dominant as sources of investment, the importance of Taiwan grew rapidly and FDI from the US, EU and Japan (often via tax-free holdings in the Virgin Islands) increased in spurts. The prominence of wholly foreign owned enterprises in total realized investment also began to grow, spiking in the late 1980s and then again in the mid-‘90s.[32] But the role of direct investment on the part of developed countries would remain subdued, with FDI from the US, EU, Japan and Canada composing only a quarter of China’s cumulative inbound FDI between 1985 and 2005. By comparison, “worldwide, developed countries accounted for 92% of FDI in 1998-2002.”[33] Meanwhile, the absolute volume of international investment skyrocketed, reaching record-high levels around the turn of the millennium. Both total investment into China and China’s share of the growing global total increased markedly in this period. Only the US and UK received more incoming FDI in these years, and both were superseded by China in the 21st century. Out of all developing countries, the Chinese share of global FDI fluctuated from between 20 to 50 percent.[34] This signaled not only China’s own reliance of foreign capital and export industries, but also its growing ability to out-compete competitors in Southeast Asia in order to secure this investment.

Figure 7

Recentering East Asia

Trends in the profit rate of the world’s major producers defined this process. It is not coincidental, for instance, that the Chinese investment boom occurred at the same time as the brief recovery of profitability experienced by US industry, particularly manufacturing. The 1990s saw GDP increase continuously in the US for the longest recession-free stretch ever experienced (just under a decade)[35] paired with declining unemployment, low inflation and rising productivity driven by the growth of computerization. Job growth reached record levels, consumer credit continued to expand, and a boom in consumption followed. This was all, in turn, facilitated by the cheapening of consumer goods produced via Pacific Rim supply chains, with China able to secure growing shares of this trade throughout the decade—ultimately at the expense of its Southeast Asian competitors.[36] In this period, the significantly more labor-intensive, lower-tech Chinese manufacturing industry did not threaten higher-tech US producers, since it specialized in goods much farther down the production chain. This sort of production was simply not feasible within the US (due to higher wages) and the profits often accrued in part to US corporations nonetheless through contract hierarchies. But US demand was only part of the picture. In the end, the Chinese ascent could only be secured through crisis.

First, the bursting of the asset bubble saw Japan’s power in the region reduced. The Plaza Accord had severely hindered Japanese domestic production, leading to a rapid outflow of capital beginning in the mid-1980s, alongside speculation at home. When the bubble burst in 1990, it threw the Japanese economy into two decades of relative stagnation. Even prior to the Plaza Accord, profitability had already declined rapidly and most major Japanese firms had responded to this by pouring capital into speculative financial devices and booming real estate markets. After the bubble burst, this left them burdened with a mass of severely deflated assets and large interest payments incurred on credit obtained during the boom. Even where profits remained steady, such firms had to increasingly direct their revenue toward paying down this debt, rather than funding new investment. This was despite the ready availability of extremely low-interest loans offered in the name of stimulating an economic recovery. The traditional monetarist response to crisis (increase liquidity and money supply) stagnated in the face of plummeting demand for new credit as firms sought to rectify their balance sheets. The Japanese state therefore stepped in to keep the economy afloat, providing a base level of demand for the banking system and funneling the money into new infrastructure or other vaguely Keynesian projects. Though this was insufficient to stimulate a full recovery, it did arguably prevent an outright collapse.[37] The result was two Lost Decades of extremely slow growth, persistently high (though not staggering) unemployment, increasing precarity among the workforce and slowly growing nationalist sentiment.

For China, the results of the Japanese decline were clear. Japanese capital was too weak in this period to act as a significant counter to the bamboo network, even though it was Japanese investment that had stimulated much of the network’s early accumulation. At the same time, low growth rates at home still ensured a steady flow of FDI from Japan into China and elsewhere. In contrast to China-bound FDI from the bamboo network, Japanese funds were not as heavily centered on Guangdong and Fujian. China-Japan trade instead helped to stimulate the boom of the central and northern coast, in particular in Shanghai, the largest recipient of Japanese investment in the 1990s. Between 1991 and 1994, Japanese FDI into China grew at a rate of 53 percent per year.[38] It peaked in 1995 at $4.5 billion, or about 8.8 percent of total FDI into China, then declined throughout the latter half of the 1990s, reaching a trough in the years of the Asian Financial Crisis before rebounding in the new millennium.[39] But despite continuing regional prominence as an investor (and dominance in R&D and high-tech patents) Japanese capital was now forced to share influence with the bamboo network, and therefore could not enforce the more rigid, Japan-centric hierarchies experienced elsewhere in the region. Meanwhile, capitalists within the bamboo network (as well as those in South Korea) would soon see increasing economic interdependence with the Chinese mainland as a profitable alternative to reliance on Japan.

The second major turning point was the Asian Financial Crisis, which began in Thailand in 1997. The profit rates of Thai manufacturing, construction and services had all begun to decline as early as 1990. Far more dependent on exports than the Japanese, South Korean or Taiwanese precedents, manufacturing had begun to confront both vertical and horizontal limits due to its position in global trade hierarchies. First, Thai firms were unable to successfully implement labor-saving technology, preventing them from moving up the value chain. Second, they were caught in a “realization crisis” that grew in intensity throughout the 1990s, in which Thai producers were unable to secure sufficient shares of market demand in the face of rising competition, particularly from China. The stagnation in Japan also meant that consumer demand in Asia’s largest economy plummeted. The US and Europe thereby became the most important export markets, and competition for access to these markets increasingly became a zero-sum game. With the Chinese share of the US import market growing from 3.1 percent in 1990 to 7.8 percent in 1998, Thailand’s stagnant, meager share of 1.4 percent throughout the same period was evidence of this “realization crisis,” and, paired with rising wages in manufacturing, led to the rapid growth of speculative investment in banking, insurance and real estate, similar in character to the Japanese asset bubble.[40]

Meanwhile, the Chinese currency reforms of 1994 had the effect of devaluing the yuan but not floating the currency entirely, further enhancing Chinese competitiveness while also retaining a moderate level of insulation from currency speculation. FDI into Thailand hit a trough in the same year, and when it recovered, the bulk of investment was in real estate, rather than manufacturing. All of this was facilitated by a wave of liberalization and deregulation measures encouraged by the Thai state. Restraints on the financial sector were lifted and, most importantly, faced with mounting debt, “the state dismantled most foreign exchange controls and opened the Bangkok International Banking Facility, which allowed offshore borrowing in foreign currencies and reconversion into Thai baht” which was kept “pegged to a basket of currencies favouring the dollar” and then floated in 1997.[41] The end result was the collapse of the real estate bubble followed by a wave of currency speculation that threw the entire region into crisis. In Thailand, real wages fell due to combined devaluation and inflation and unemployment more than doubled. Laid-off workers funneled into the countryside, raising the rural poverty rate and leading to a wave of populist unrest. In Indonesia, inflation grew rapidly, a wave of anti-government and anti-Chinese riots shook the country, and the Suharto regime was forced to resign. In South Korea, the stock market crashed, financial institutions collapsed, a number of chaebols were restructured, bought out or went bankrupt, and the IMF had to step in to bail out the severely indebted government.

Though growth and investment in China also declined, the worst of the crisis was avoided. The US remained a strong export market (and would become even more important after its own dot-com bubble) the yuan was protected from rampant speculation, the profit rate of manufacturing remained robust, and, most importantly, all of China’s major regional competitors were essentially eliminated. The result was that, by the end of the millennium, mainland China would become the center of a new Sinosphere of capital, soon capable of outcompeting the Japanese for economic hegemony in the Pacific Rim. Maybe most importantly, this sequence of Asian financial crises was convincing justification for new experiments in monetary control, finance and the management of major conglomerates, emphasizing the ability of the Chinese capitalist class, coordinated by the party-state, to intervene in dangerous cycles of speculation driven by the parochial interests of smaller fractions of the class. This logic of monetary protection and managerial oversight would define the restructuring of core industries at the turn of the millennium. But China’s integration into the market could never be entirely immune from the same dynamics that had plagued its neighbors.

Debts

Though ultimately key to its success, these regional crises also combined with new domestic limits to threaten the stability of the Chinese transition. Another period of retrenchment had followed the events in Beijing in 1989, as leading reformers were purged from the party, inflation was reigned in and planners sought again to scale back the extent of the market. But the very attempt to restrain the force of the market only created the conditions for it to extend even farther. On the one hand, the suppression of the unrest generated by the unevenness of the transition helped to restore stability to the economy, and this stability would convince international investors that conditions were secure enough to guarantee future returns.[42] On the other hand, the unrest itself was a signal of deeper crises. Throughout the 1980s, local leaders were encouraged to funnel massive amounts of capital into TVEs and commercial real estate development, regardless of risk. In order to facilitate this process, hundreds of unregulated banks sprung up across the country, themselves becoming a seemingly lucrative investment in the process. Non-existent financial policy had paired with booming growth to create a massive TVE bubble, probably the first distinctly capitalist crisis of the new era. By the early 1990s, it had become clear that many TVEs were simply not productive, commercial real estate was often extremely overvalued, and the new banks were mostly composed of bad loans.

Meanwhile, since the events in Tiananmen had seen a brief credit embargo levied against the country, the trade deficit had grown just as access to external funding was temporarily limited. Part of the retrenchment, then, was an intentional attempt to reduce domestic demand for investment by imposing strict quotas and suppressing wage increases. Bank credit slowed, growing only 10.6 percent between 1988 and 1989, compared to almost 30 percent in previous years. A drop in fixed investment followed, declining eight percent in 1989, and plummeting “from 32% of GDP in 1988 to 25% in 1990.”[43] The state again increased its share of total investment, and the demands of urbanites were partially met with a renewed focus on shielding SOEs from the effects of austerity. But aside from a few preferential policies for urbanites, new price controls (especially on producer goods) and some increased planning allocations, the conservatives within the party were now unable to offer any truly extensive plan to scale back reforms or even to solve the many problems that had arisen from the instability of the transition. Instead, they seemed cursed to repeat the same minimal, insufficient program that had been offered whenever reform seemed to get out of hand. And, again, the effects were to induce a recession that helped to clear the market, restore stability, and create the conditions for a new wave of reforms.[44]

The recession saw consumption decline alongside investment, with households withdrawing what money they could from speculative schemes and pouring their income into savings accounts. The drop in demand also eliminated the persistent shortages that had built up in the last years of the 1980s, and this in turn allowed the market to re-orient toward less speculative sources of demand. Despite the credit embargo, foreign markets remained open to Chinese exports and the SEZs to FDI. For the first time, exports began to consistently overtake imports as a share of GDP.[45] Meanwhile, unemployment increased, particularly in rural areas, providing an ever larger reserve army of labor for coastal production hubs. Paired with the collapse of socialist regimes across Eastern Europe (and soon the USSR itself), the growing surplus population seemed to forebode future unrest. But conservatives had no functional plan to reignite growth or to incorporate this population back into the planned economy. Meanwhile, foreign investment had already started to pour in from new locations such as Taiwan, eager to exploit the same factors that had begun to catapult Hong Kong into a hub for global finance.[46]

The attempt to shield urban SOEs from the worst of the recession, though marginally successful at stifling further discontent among workers, ultimately caused a shift from the slow, competition-driven profitability growth seen in the late 1980s to a rapid plunge in profitability in 1989 and 1990. As the share of unprofitable SOEs began to grow, the state sector itself became less and less reliable as a source of funding. This further undercut the state’s potential to act as a stand-in for the market.[47] While such trends continued to erode the basis for any large-scale return to the plan, a new reform agenda was slowly cobbled together in response to the many macroeconomic policies that conservatives seemed unable to address. Central to this agenda was the reform and consolidation of the banking system, which would streamline access to household savings. This was a lynchpin reform, finally cutting through the recurring crises of state investment and placing the financial system on an entirely new foundation. Such a change had only become possible because rising incomes (now more often monetized) had ensured that personal savings had been increasing rapidly from 1978 onward. Soon, this mass of household savings would serve as the single most important source of investment, capable of replacing the declining contributions of the state-owned sector.[48]

At the advent of the transition period, there was no true banking system in China, and the only financial model readily available was a rough blueprint left behind by Soviet advisors in the 1950s. Nominally, there was a single bank: the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), which was a sub-department within the Ministry of Finance, employing only eighty people in 1978 and serving almost none of the functions associated with banking. But the TVE boom in the 1980s both expanded demand for investment and made evident the need for an investment infrastructure outside the planning apparatus that would be capable of dealing with the dispersion and complexity of the emerging industrial structure. The result was a rapid, largely uncontrolled proliferation of financial institutions over the course of the 1980s, including everything from banks to pawn shops: “By 1988, there were 20 banking institutions, 745 trust and investment companies, 34 securities companies, 180 pawn shops, and an unknowable number of finance companies [including local ‘banks’ and credit unions] spread haphazardly across the nation.”[49] All of this was done in the name of financial “modernization,” with new financial institutions emerging at every level of government and thereby mirroring the decentralization of the planning infrastructure that had taken place in the middle of the socialist era.

Throughout this boom, it was actually local-level party cadres who held institutional power over the banking system and drove its rapid expansion. Throughout the decade, the PBOC, for instance, had its senior branch managers appointed by the local party organs, rather than the central state. Just as in the decentralized planning apparatus of the socialist era, the structural interest of local party committees was to stimulate growth, since their political performance was measured by the economic output of their district. Now, however, growth was no longer measured in just sheer output, but often in value, and specifically “value-added” for export. At the same time, there was the added benefit of embezzling funds, signing lucrative contracts with Hong Kong (denominated in valuable HKD or USD), and profiting directly off the labor of workers within the new enterprises. In the past, similar structural pressures had encouraged cadres to exaggerate output, particularly in key industrial or agricultural products, in order to secure more material from the central state’s investment apparatus. The same sort of exaggeration occurred in the 1980s, but now it had a more distinctly speculative sheen: every district’s real estate and TVEs sectors were portrayed as unassailable growth industries, with each new wave of investors gaining an interest in maintaining the illusion, at least until they could sell their own shares. Rather than exaggerating output in order to secure additional investment from the central state, local governments set up their own inconsistent, speculative and extremely volatile financial infrastructure in order to attract the growing bulk of floating, non-plan profits and personal investment funds. Between 1984 and 1986, the number of loans grew more than 30 percent each year, then lowered slightly to just over 20 percent per year from 1987 through 1991. This, in turn, stimulated rampant inflation, and when the state attempted to impose some administrative control on the new financial system the result was a run on local bank branches, helping to stoke building unrest in the final year of the decade.[50]

The conservative retrenchment, however, simply sought to clamp down on credit, stifling total investment in the hopes of shifting the economy back onto the planning infrastructure. But the state-owned sector was already far too dependent on the non-plan economy, and the attempt only accelerated its atrophy. Aside from the anemic plan and the volatile new banking system, there was simply no other infrastructure for investment. The initial revival of reform that followed the retrenchment, then, was both dependent on this extremely unregulated financial system and tasked with forcing it through a painful period of restructuring. Ironically, it was the new reformist regime that would burst the bubble. The events of 1989 had already proven how volatile rampant inflation and uncontrolled speculation could be. Now, with the SOEs falling into deficit and the banks that had financed them holding more and more bad loans, the need for widespread financial reforms became evident. In the same year as Deng’s Southern Tour, a global recession hit and inflation again skyrocketed, threatening the revival of the reform agenda. But unlike in the ‘80s, reformists had at least formulated a rough solution to the problem. Now, rather than the vague blueprints left by Soviet advisors, the state turned to the American financial system as a model. The effort was led by Zhu Rongji, the former mayor of Shanghai who was promoted to vice-premier in 1991 for his successful management of the city. Concurrent to his term, Zhu also served as governor of the People’s Bank, where he oversaw monetary policy. In this dual capacity, he began to impose nationwide financial reforms beginning in 1993, just when annual inflation in large cities had again surpassed twenty percent. The economy was pushed into another period of austerity—but this time it was imposed by the reformist faction, rather than by the conservatives.[51]

First, decentralization was addressed at multiple levels. The tax system, which had become a mess of locally negotiated tax rates, often specific to each enterprise, underwent sweeping reforms in 1994. These reforms were modeled on the federalist systems used in many Western countries, with tax categories clearly defined and apportioned between central and local governments. Given the level of decentralization that had become the norm both politically (from the 1960s onward) and financially (from the 1980s), the net effect of these fiscal reforms was to begin to recentralize fiscal authority, and thereby increase the ability of the central state to actually carry out its own policies.[52] At the same time, the financial system itself was centralized, with the proliferation of unregulated, vaguely-defined small investment mechanisms consolidated into a more coherent infrastructure dominated by the “Big Four” state-owned commercial banks: Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC), Agricultural Bank of China (ABC), Construction Bank (CCB) and Bank of China (BOC). Each of the Big Four were given a slightly different mandate, ICBC dominating lending and deposits in the cities, ABC doing so in the countryside, CCB providing project financing and BOC handling foreign trade and foreign-exchange transactions. Alongside the Big Four, three major policy banks were formed: China Development Bank, Export-Import Bank and the Agricultural Development Bank. These banks were tasked with implementing policy projects announced by the central state, such as large-scale infrastructure construction or the international promotion of Chinese exports. By the turn of the century, the Big Four alone would control more than half of all capital held by all banking institutions and the policy banks another quarter. The remainder was composed of smaller credit unions, the postal savings system, and joint-stock commercial banks, all of which were dependent on the Big Four, which still today dominate interbank lending.[53]

The double-collapse of the Hainan real estate bubble in 1993 and the Guangdong International Trust & Investment Company (GITIC) in 1998 illustrates the general arc of the era: severed from Guangdong and made into both a province and an SEZ in 1988, the poor tropical island province of Hainan saw a sudden influx of young speculators, with investment coordinated by twenty-one unregulated trust companies, the largest of which were effectively the financial wings of provincial governments. Though modeled on Shenzhen, the Hainain SEZ seemed to always push the development of export industry (and exploitation of local natural resources) off into the near future. Instead, the SEZ’s policy permitting the sale of land-use rights encouraged the bulk of these speculators to go straight into real estate. In the space of a few years, “20,000 real estate companies materialized—one for every 80 people on the island.” Even the port was purchased (by a Japanese developer) and turned into massive condo towers, since industrial land sold for far less than residential. After Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour in 1992, reaffirming commitment to the reform project and the importance of Southern China in this process, it seemed that nothing could stop the ascent of Hainan’s real estate values.[54]

But in reality, the very beginnings of Zhu Rongji’s financial consolidation destroyed investor confidence in the Hainan bubble, which began to collapse as early as 1993. The burst bubble left a mass of bad debt that amounted to some ten percent of the national budget, accrued in a single SEZ over the course of five years—and Hainan was soon stripped of its SEZ status as well.[55] But despite this one collapse early in the decade, most of the country’s larger financial problems persisted: the deficits in the SOEs had never been resolved and the accumulation of non-performing loans simply could not be ignored much longer. This became strikingly clear with the bankruptcy of the GITIC in 1998, during the Asian Financial crisis. This was “the first and only formal bankruptcy of a major financial entity in China,” and GITIC had controlled much of the international borrowing that went into Guangdong, by then the country’s richest province.[56] Compared to the national crises that struck most of its neighbors in Southeast Asia, the GITIC collapse was relatively contained. Nonetheless, the dual failure of Hainan and GITIC proved that a financial system driven these volatile trust and investment companies could threaten a similar financial crisis in China.

This further stimulated the centralization of the Big Four into the hands of the central government, but it also led directly to the implementation of the second major component of financial reform, again spearheaded by Zhu (though formulated by Zhou Xiaochuan, head of the CCB), and again modeled on the American system: the plan was to spin-off all the bad loans now held by the Big Four into a series of asset-management companies, which would then salvage what could be salvaged from the original investments over a number of years—essentially the exact same method used by the US in dealing with the Savings & Loan Crisis. This would repair the balance sheets of the Big Four and bring the Chinese financial system more generally in line with international standards. The process, however, was never completed, and its failure would leave the Chinese financial system both dependent on bank financing, backed by consumer deposits, and particularly prone to inflating ever-larger speculative bubbles for the sake of maintaining investment.[57]

Rural Boom & Crash

These national financial reforms had an equally devastating effect on the countryside, where a bubble had long been building. Initiated in the 1980s by rising rural incomes, the rapid growth of rural industry and the resurrection of rural markets, the 1990s would see the final stage of this rural bubble, capped by its collapse. The integration of the TVEs with the rapidly restructuring urban industrial sector (the SOE-TVE nexus, explored above), was one factor in this collapse. But beyond such external dependency, the rural bubble was riven with entirely endogenous contradictions that all but guaranteed an ultimate crash. Throughout, agriculture remained heavily shielded from the pressures of the global market and rural land remained nominally communal. These very protections provided the basis for rising incomes and relative stability. Paired with the rapid, largely unregulated growth of competitive rural industry, however, these conditions would create a boom and crash that would definitively destroy the socialist countryside.

After the wake of 1989’s urban protests had settled somewhat, the state began re-implementing serious market reforms for urban food subsidies. These food subsidies, a holdover of the socialist developmental regime, had acted to reduce the cost of living of the urban working class. But attempts to restructure these programs had been put on hold because of the rampant inflation caused by price reforms in 1988 and 1989 and the unrest that followed. Ironically, then, it was the violent and decisive suppression of these urban protests that made the unpopular reforms possible. The new reform package was a continuation of earlier attempts to reduce the impact of subsidies on state expenditures, which had risen again in response to late 1980s inflation. But, unlike in the early 1980s, this time the state attacked urban food prices instead of rural procurement prices. Urban grain prices were liberalized in 1991 (raising the urban price of grain by 35 percent) and 1992 (raising it by 25 percent), and by 1993 the official system for urban food rationing was ended. Rising agricultural prices likewise stimulated production, feeding into growing rural incomes and the expanding rural economy. Farm product prices, rural incomes, and rural purchasing power grew.[58] The loosening of credit in late 1990, following a period of retrenchment after the inflation and protests of the late 1980s, began a period of rapid rural economic growth.[59]