The following was written at the request of Reignite Press. A Chinese version from Reignite is now available here. In addition, a second translation partially based on the first, but in a different style can be found here.

–Chuang

Since the Arab Spring in 2011, the world has been riven by abrupt tectonic shifts in the landscape of political potential. The certainty that once embroidered every discussion of the global economy has, after a decade of crisis, become a laughable afterthought. In retrospect, we might argue that the “Rebirth of History” began in Algeria or Egypt, but now history is beginning to shake loose even in the wealthy countries, beneath the sprawling, shining cities built on decades of speculation. Places once considered stable ground—requiring little more than periodic tending by the technocratic management of central banks and think tanks—have now shown themselves to be founded on fault lines.

So what does history look like when it reawakens in Hong Kong? You have a better vantage than us, certainly—eyes weeping in the teargas, blood on the teeth, the grit of cement and asphalt, dust and sweat. This proximity has benefits, and no one who has not felt it can truly communicate what you all have felt and done and suffered in the past half year. But there’s also a certain claustrophobia: bodies pressed together, police shields pushing forward, tangled brawls on the MTR. Sometimes, proximity can strangle perspective. In the midst of something like this, the smallest battles loom like wars and the most petty arguments can take the form of epic confrontations. Sometimes receiving an outside view helps refocus the terrain, like glancing at a crowdsourced streetmap of police positions when you’re trying to outmaneuver the enemy.

Seen from afar, the logic behind events is often opaque. But the intensity of the struggles also means that those in the distance will invariably turn an opportunistic eye toward your movement, wielding it like a bludgeon in their own local battles. This is often passed off as “solidarity” by activists, and is largely harmless, insofar as it remains a social media performance—since such people have little power and can offer nothing in the way of material support or opposition. This attention takes a more dangerous shape, however, when it originates from politicians and businesspeople who have the capacity to set the machinery of the state working in different directions. Thus, a visit to Hong Kong by a politician like Ted Cruz has compounding implications, as do the various protests by Hong Kongers waving American flags and seeking more or less direct intervention by the US—even going so far as to appeal to Trump himself. Now that the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act has passed through the US legislature and received its endorsement from the president, the complications of these tactics are becoming evident.

Such events have had mixed reception in the US, and certainly elsewhere. On the one hand, those who consider themselves a part of “the left” have scorned images of Joshua Wong testifying before congress or Ted Cruz standing with protestors in the Hong Kong airport. The points of their critique are banal, and basically amount to a scolding of naïve Hong Kongers for reaching out to the morally compromised rightwing of the US government. Maybe some of you are idiots (in which case your feelings might be hurt), and maybe some of you are the enemy (in which case, who cares). But, otherwise, it’s safe to assume that you—like basically anyone else in the world—know that America is not your friend. The leftist critique thereby tends to miss the point entirely. Sometimes, however, a more nuanced version of this critique does gesture in the correct direction, emphasizing that US intervention may not be as feasible or as desirable as might be assumed. This is an angle that we will return to below.

Joshua Wong and Denise Ho testify before the US Congress in support of the legislation that would become the Hong Kong Human Right sand Democracy Act [Olivier Douliery/Getty Images]

On the other hand, it’s safe to say that the general reception in the US has been largely positive. In part, this is due to the stoking of a new Cold War discourse by the American rightwing, which tries to disguise its own increasingly authoritarian character by pointing again at the Peril approaching from the East. This at least accounts for the widely supportive reaction the struggle has received in the Western media—something never afforded to the near-insurrection in Ecuador, or the burning of Paris, and certainly not to our own domestic unrest. This often exuberant support given to the protests (even when violent) by the massive media monopolies has provided a test case where we are able to see some of the real popular support that exists for such events. It’s not possible, in this sense, to reduce the support for Hong Kong among regular people in the US to a simple matter of rightwing brainwashing. Instead, we might argue that the positive reception has given us a glimpse into what conditions look like when, for once, the media are not alternately obscuring or condemning events on the ground but are, in fact, reporting on them.

It is informative, then, to look at how events in Hong Kong have been portrayed in the West, and in the US in particular, and how Hong Kongers have sought to appeal broadly to the US public (or specifically to US politicians) in the hope of some sort of intervention. In the Western media, we see an unending emphasis on the vague “democratic” aspect of the movement, which is never defined nor delved into. This helps to craft the presumption among the audience that people in Hong Kong are simply protesting in the hopes of obtaining something that looks more or less like the US political system. Certainly this is the case for some Hong Kongers, for whom the logic of the “enemy of my enemy” has penetrated deep into the blood—resulting in an incurable degradation of the mental faculties. But we suspect that those who wave the American flag with any earnest belief in their hearts are fewer than either the media or “the left” might presume.

Ted Cruz visiting Hong Kong in October, 2019 [Credit: CNN]

The simple fact is that, due to the city’s structural position in the chain of global power, it’s hard to imagine any version of the Hong Kong protests that wouldn’t be forced to dirty its hands with geopolitical appeals to some degree. It’s a basic gambit against the worst repression: good press in the US, and favor among US politicians (who cares which side of the one-sided political machine they’re on, anyways?) both tip the scales ever so slightly against a mainland military deployment. The one drawback is that it becomes much easier for the Chinese state to draw on such appeals as evidence of foreign influence. This might be inevitable, in the end, but it does drive a subtle wedge between Hong Kongers and potential allies on the mainland. The blatant way in which most protestors have thus far ignored the prospect of such alliances is, by the way, the clearest weakness of the movement. But, in the end, even if we attribute the Westward appeals to necessity, it’s easy to get too full of oneself, talking about the hard sacrifices of Real Politik as if every protestor were a Henry Kissinger in miniature. To do so, however, is also to forget that the competing interests of national polities envisioned by “Real Politik” has always been a myth obscuring the brazen, unilateral deployment of American power across the globe.

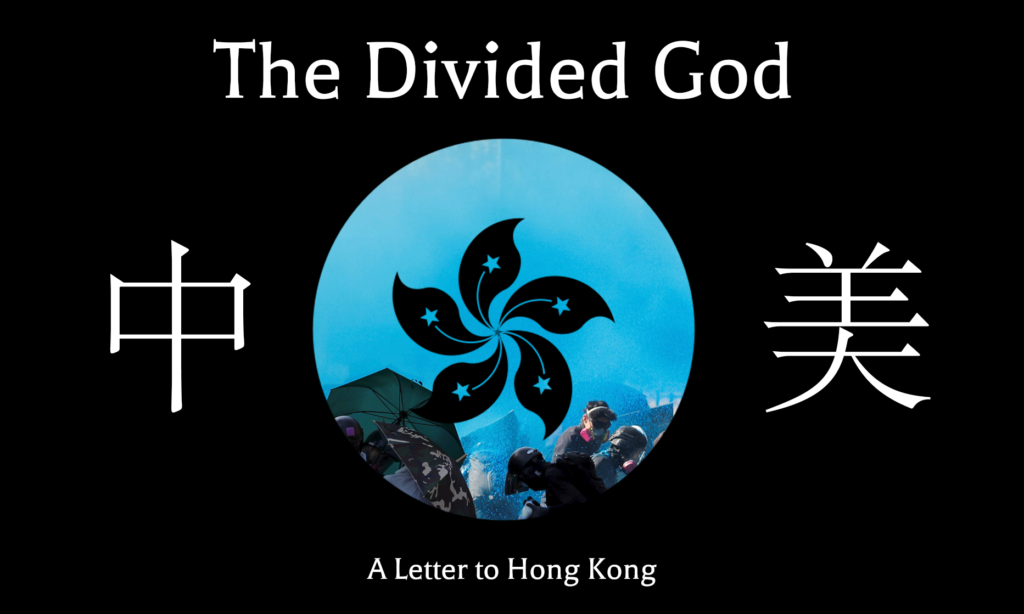

It’s true that Hong Kongers have a very narrow territory on which to maneuver. But this only makes it more essential that the actual terrain be as clear as possible. And right now the landscape is becoming more and more obscured in a fog of geopolitical fantasies, blinding protestors to the potentials that lie on the mainland while also drawing them toward the false light cast by the distant American behemoth. What does this mean? Let’s use a simple metaphor: right now, Hong Kongers talk about the US and China as if they are two gods standing atop a mountain, locked in combat. The hope is that, in order to avoid being crushed under the feet of China, Hong Kongers must petition the opposing god for protection. Maybe America will reach down from the clouds to cradle Hong Kong in its hands, or maybe it will simply shield the island from some of China’s stomping wrath. Maybe not even this much. For years, protests in the city have declared that Hong Kong is dying, or that it’s already dead. So maybe the hope is just that Hong Kong’s blood debt be repaid—and what god is more suited for such an appeal than the bloodiest and most vengeful?

[Credit: Justin Chin/Bloomberg]

But the two countries are not gods, of course. In fact, they are not even two countries in the sense presumed by geopolitics. China and America are merely two of the major portions of a single global economy riven with contradictions. When these contradictions intensify, it appears that these two parts of a single body, turned against one another, are two distinct bodies in conflict. It’s easy to make the mistake. As the gods battle in the clouds we rarely dare to look up, busy as we are trying not to be crushed. But if you do glance above into the darkness, you can begin to see the outline of something different: instead of two gods in political combat, a single, monstrous deity emerges through the mist, its body knit together not by statecraft but by economics. Even more horrific is the realization that you yourself—your country, your city, no matter where—are a miniscule, subordinate part of this single deity spanning the earth. Only once you glimpse its face do you realize that there were never two gods battling on the mountaintop, but always one, divided against itself, claws ripping across its own chest, sharp teeth snapping at its own ankles, dancing wildly as it tears its body apart and the world with it. Right now we are witnessing only the initial steps in this dance, a few specks of blood that foretell the still-distant future. But gazing upon the reality of the god of the global economy, united in division, nonetheless leads us to conclude that neither China nor America can win, and if Hong Kong bets on either one it is betting on failure. As if it weren’t clear already: you are all already part of the body of the global economy, even while you are crushed beneath its weight.

The point is this: Never trust anyone who speaks of the world in purely geopolitical terms, as if there are simply “nations” that have “interests” which sometimes conflict. Geopolitics is a hologram projected over the harsh reality of the economy, disguising its globe-spanning mutually-assured evisceration in the melodrama of political leaders and public sentiment. The position of Hong Kong is certainly precarious. But this means that it is absolutely essential to see through the mirage of geopolitics and perceive the true terrain of global power, which is fundamentally economic. Specifically: economic in the sense of the social organization of our collective capacity to produce things, not in the limited sense of “economics” that we’ve become acclimated to, in which the economy appears as little more than the Manichean forces of supply and demand playing out on abstract markets, with no attention to production or society at large. What appears to be a geopolitical conflict between two distinct groups of political leaders can then be accurately perceived as a contradiction between two fractions of a single class of economic elites who control society’s capacity to produce and distribute goods.

Contradiction is a vague term, so let’s be more explicit about what an “economic contradiction” is, exactly. When we say that there is a single global economy, but that it is riven by contradiction, what we’re saying is that, contrary to mainstream economics, there is no “equilibrium” in a capitalist system. Capitalism is the name for the presently existing social and economic system in every country of the world, because each of these national economies is a) linked in a chain of dependencies to the others and b) all are fundamentally driven by profit. This is a simplification, of course, but only one detail is necessary here: the drive for profit is administered by the small minority of people in each country who own the majority of things in that country—but especially the land, the factories, the farms, the stores and warehouses and the myriad machines that are used to make things. This minority of elites exercise their ownership through the industrial, commercial and financial firms that they are invested in, each of which is in competition with others in order to secure larger shares of the market and thereby make a profit. As firms fail, they are eliminated or absorbed into others, tending to create larger monopolies as time goes on. These monopolies are then often loosely united along national lines, even while they are international in scope, because they all suffer the fiercest competition from newer firms with better technology and cheaper labor in other countries. It is this competition between clusters of large companies in different countries, each yoked to national currency systems valued on international markets, that composes the nature of a “trade war,” as countries each seek preferential treatment of their own national industries and preferential movements in the value of their own national currencies. This is what is meant by “economic contradiction” in this context.

One strategy to confront this competition is for larger, older companies from the richer countries to outsource more of their production to the new competitor countries, creating a compact that supersedes the more vicious forms of competition. Hong Kong is of course familiar with this, since it was the site of such a compact between the US and China: as US (alongside European and Japanese) firms sought to outsource low-end production to the Chinese mainland, Hong Kong became an essential interface, providing the financial and cultural networks necessary to mediate between the two. This was possible because of Hong Kong’s physical and cultural proximity, which had allowed the city to rapidly deindustrialize by outsourcing its own production to the mainland far before the US began to follow suit, as well as its distinct legal-political status, which allowed it to act as a sort of airlock protecting the mainland from the turbulence of global markets in the process of its transition to capitalism. But such compacts are based on pre-existing inequalities in industrial capacity. The US outsourced to the mainland because it was being confronted by rising costs elsewhere in East Asia. Not only had wages begun to rise in Taiwan and South Korea, but in certain industries (like microchip fabrication), these countries had risen to join Japan and Germany as direct competitors in the markets that mattered most. Today’s trade war is simply the result of this compact slowly dissolving as China exceeds its subordinate position. No longer a poor country that can funnel seemingly infinite cheap labor into value chains helmed by US monopolies, China now has less to offer the US and more to threaten it with. Meanwhile, the wealth accrued to Chinese elites in the years of the US-China compact makes reliance on foreign capital less essential, though not yet unnecessary. Again: what we are calling a “trade war” today is really just a foreshock of the US-China compact beginning to dissolve. It is certainly not a signal that the relationship has already splintered into total antagonism.

But what does this mean for Hong Kong? What are the practical consequences? The first harsh conclusion is that you have never had and can never have “one country, two systems.” The illusion of relative autonomy that persisted after the handover was fundamentally a result of the US-China compact, which required the autonomy of Hong Kong in order for the city to be able to turn RMB into dollars and route foreign investment into the mainland. This is the basic structural fact that sustained the brief illusion of “one country, two systems.” Now, with the mainland more directly open to global markets, Hong Kong is simply one of many potential sites for financial services, preferable to others only because of its existing infrastructure, experience and established relationships. This isn’t to say it is unimportant to the global division of power, however—in fact, the mainland’s attempt to effectively replace the Hong Kong financial hub with producer services offered in Shanghai has thus far been much less successful than the state desires.

But this also means that the apparent invasion of the mainland into every corner of the city is not the replacing of Hong Kong’s colonial-heritage system of liberal capitalism with some sort of “authoritarian socialism” or, if you want to sound like a real idiot, “Communism.” What is happening in Hong Kong is happening basically everywhere: cities are becoming unaffordable for everyone but a small elite, surveillance is expanding onto every street and more and more people are being imprisoned in ever-growing jails, prisons and “detention centers.” It’s happening in America, where it takes on a racial character; and it’s happening in mainland China, where it’s justified in the bare terms of national unity and a crackdown on extremism. There are no “two systems” left. There is only one: capitalism. The crisis in Hong Kong is not a crisis of mainland invasion, then. It’s a crisis in which the face of capitalism has been clothed in the Chinese flag just as the financial position of the city has begun to erode, forcing people to realize that serving the needs of the economy produces an increasingly unlivable world. Hong Kong is gradually becoming unnecessary for mediation between the mainland and the rest of the global economy. It survives through inertia, and this means that more and more of the city’s economy is sustained on growing speculation. In these conditions, do you really think that the real estate investments of Xi’s family have a different effect on your life than those of Li Ka-Shing? Of course not. Contracts written in Cantonese read the same as those written in Mandarin.

Second, this means that appeals to US power by Hong Kongers, while not necessarily useless, can have only a limited effect. Since there is a single global system helmed by American power, it is impossible for Hong Kong to secede from the mainland and join a different sphere of influence. The mainland is itself well within the American global power structure, even if its increasing competition with US industry forces it to pose itself as something starkly separate. Similarly, it is impossible for Hong Kong to leverage its position as a free port to participate in and profit from the global economy without having to integrate itself with the mainland—which is where the bulk of goods passing through the port originate, after all. This is also precisely why the Chinese state has been fast-tracking integration with the “Greater Bay Area” of the Pearl River Delta, since Chinese policymakers accurately perceive that the only hope for Hong Kong’s economic prosperity under the status quo requires more thorough connections with the mega-urban complex across the water. As the divided god tears itself apart, an appeal to either of its halves will do nothing to save this island extremity crushed beneath the weight of the conflict.

What would such a scenario look like in China, though? The results are hard to imagine, since these events would be taking place at a much larger scale. Additionally, Japan’s submission to American power occurred in an entirely different context: already part of a thoroughly US-centric military-economic alliance, Japanese industry was never as central to the entire global economy as Chinese industry is today. Meanwhile, when Japan’s crisis occurred, it was softened by the emergence of other East Asian manufacturing hubs, including China, which took up the slack in global production. When the divided god struck against its Japanese portions, it was like cutting off an arm, knowing full well that it could grow back. But striking against China today is more akin to the global economy stabbing itself in the heart.

The results might be slow and subtle, China falling further into a middle-income trap, growth slowing even more in the high-income countries, new small wars breaking out in the global hinterland. In this case, Hong Kong largely remains in the same situation, dying of attrition. But, albeit less probable, the results might be more spectacular: a balkanization in China like that experienced by the Soviet Union, each faction of elites ruling as disunited oligarchs, new military incursions by an American empire hoping to rejuvenate itself. In this scenario, it seems as if Hong Kong could gain independence. But political independence is predicated on economic independence—and what could Hong Kong do or produce in such circumstances? It could only survive by cultivating the exact same sort of corrupt ties it currently holds with the exact same mainland oligarchs, but now on a province-by-province basis. Is it really that much better to pay tribute to the warlord rather than the Emperor?

The Chinese Navy engages in a drill in the waters near Hong Kong.

The second possible scenario is hardly more desirable. The size, scale and situation of China’s economy is not comparable to that of Japan. China retains much stronger control over its own currency, much greater capital controls, and, most importantly, is not and never has been part of the US Pacific military complex. In fact, it has largely been the object targeted by that complex, placing it in an antagonistic submissive position, rather than the collaborative submission of Japan. This means that if China refuses to submit to a Japanese-style defeat, the competition between these two fractions of the global capitalist class could well escalate to a level of antagonism not seen for half a century. In many ways, this would be the return of “classical” imperialist rivalry, and it would involve the formation of currency, capital, trade and military blocs aligned with different powers. However, it is an utter mistake to think that such blocs already exist, and that it is therefore possible to side with a US bloc against a Chinese one. As already argued above, this is not at all the case today. And, were such blocs to form over the next ten to twenty years, it really doesn’t matter whether Hong Kong would be forcibly integrated with the mainland, or if some version of “one country, two systems” could survive in the shorter term—the only salient fact is that a Hong Kong too closely allied with the US would be a city doomed to destruction. In this sense, a strong diplomatic intervention by the US in today’s struggle could, in fact, be a much worse option than it appears.

In such conditions, the least violent outcome might be a true return to Cold War conditions, with the world split between two superpowers threatening it with military destruction. This differs in significant ways from the hyperbolic presumption that we exist in such conditions already: The divided god could split down its middle, both sides suffering and lashing out at the other more viciously because of it. But in this war, unlike the Cold War, each side would be the economic twin of the other—two sides of the same capitalist system severed from itself, with each side starving as it seeks to strangle its sibling. In such conditions, Hong Kong would remain the site of a protracted proxy war, before its eventual occupation by the mainland. Some today hope that, in such conditions, Hong Kong might become an independent city-state, similar to Singapore but backed by the direct protection of the US military, like a Taiwan in miniature. Geography and history, however, are major limits to such a possibility. The existence of the Taiwan strait is and always was crucial to the deployment of US naval power, as was the context of the unified Sino-Soviet threat. Without such a strong geographic divide or powerful military enemy, it’s not at all probable that the same level of US force could be deployed in the defense of Hong Kong. And it certainly isn’t possible anytime in the next few years, exempting an unimaginably reckless turn within the American electorate.

But even the idea that we are entering a new Cold War is a hopeful presumption, since the Cold War itself was premised on two loosely equivalent military superpowers locked in slow, strategic combat. Today, the US has no equivalent. China is weaker in every respect, capable of fighting and maybe winning a defensive war, but utterly incapable of threatening an offensive one. Were tensions to escalate in this direction, the result would be less a slow strategic battle between two equivalents and more the sequenced outbreak of a kind of global civil war, as region-scale conflicts break out in the face of a waning US hegemony strained by the conflict with China. This option—of a third World War that somehow avoids nuclear annihilation—is hardly something to cheer on. But, combined with the vast destruction wrought by climate change, it is the only thing capable of restoring profitability to the global economy in the long term. How would Hong Kong fare in such a conflict? So many conditions would have to change for this to even be possible that it is hard to speculate. But, frankly, it seems most probable that the city would likely be burned to the ground—maybe by China, ousting “infiltrators” and those who “provoke quarrels,” or maybe by the US attempting to “liberate” the city in the same way that they “liberated” Baghdad.

It seems that we are out of options, then, simultaneously welded to and crushed beneath the feet of the mad god in its world-rending dance. But history is not made by gods. It is made by people, and this is a lesson that you in Hong Kong are learning quickly. Whether you like it or not, the city is no longer just an island. Instead, it has become part of a global archipelago of class conflicts, as a new outbreak of struggles encircles the world—from Haiti to Ecuador to Chile, then across the ocean to Catalonia, Algeria, Lebanon, Iraq and, of course, the many hopes and tragedies of Kurdistan, before moving farther east to Indonesia and finally, Hong Kong. The participants in this archipelago of struggle may not be connected in any direct way, but all have risen in fire to stand above the sea of the status quo. Islands of struggle like this form because the deep tectonic forces of history do not press evenly on the world, nor do they press in one direction only. The earth buckles first in some places and later in others, and too often these fiery islands are just as quickly submerged. They drive in different directions and seem essentially unconnected because, for the most part, they are. The only force connecting them is the fact that they are all products of the rebirth of history and thereby act as windows into the future. More islands will form and, to survive, they must eventually converge. These struggles open a different kind of wound in the body of the global economy—a sort of mutation, we might say, which threatens to transform the fundamental ways that society organizes production.

Meanwhile, the old political positions are being eroded under this onslaught of struggle and repression. In Hong Kong, people might try to cling to the terms inherited from smaller, more limited events in the past, calling themselves (or others) pan-democrats, localists, advocates of semi-autonomy or city-state status. But the reality is that all of these terms are obsolete, because they have not arisen from the historical movement—talk to any of the young people on the street and only a miniscule fraction would identify with any of these designations. This does not mean that politics as such is obsolete, though it always appears this way when something of truly historic scale occurs. Slowly, distinct positions will form from the new conditions. They will first arise to try and answer the question of “what to do” in the long term of the movement, and then the initial, broad answers will subdivide before being able to gain more purchase. The strongest subdivisions will not be based on the largest analytic differences (i.e. independence vs. one-country-two-systems) but on the largest tactical disagreements since these tactical divides help to focus the relevance of theoretical differences (i.e. should only mainland and police property be attacked, or should the property of local capitalists begin to be included as well—and what happens when previously supportive Hong Kong elites say enough is enough and call for an end to the protests?). The evolution of the city into Yellow versus Blue is the first stage of this process—supporters of the movement against its enemies, and then subdivision into Red and/or Black to designate the most direct outlets of mainland power, and Green for more ambiguous institutions. But eventually there will be a need for more detailed articulation of why and how this power should be opposed, and this will require analysis.

Graffiti reading ‘I’d rather be ashes than dust’

From this analysis, more coherent political positions will arise. Those that adopt the limited geopolitical view outlined above will be setting themselves on a course for disaster. The tactical choice to wave American flags is attractive in the short term, and maybe has been essential to gaining the minor protection offered by large-scale global media coverage. But in the long term, such tactics sorely misinterpret the terrain. More dangerously, they tend to widen the gap that lies between the Hong Kong protestors and their potential allies among dissatisfied workers on the mainland, whose prospects are stagnating as the economy slows. This enables the mainland government to use events in Hong Kong to stoke nationalist passions, which helps to redirect domestic dissatisfaction toward an “outside” enemy. Though it seems that this hatred is fully internalized, it is very clearly a result of a large-scale mainland media apparatus displacing hatred of the wealthy as such onto hatred of the relatively wealthier youth of Hong Kong—a subtle but essential difference. The types of alliance that are most threatening to the power structure always tend to be those that are both most natural and most difficult to actually build, because so much effort is put into making such alliances appear unnatural or impossible. In this way, it is just as likely that aggressive appeals to the United States will have exactly the opposite effect as that intended, doing little to garner American intervention but ensuring a hardening of nationalist reaction to the movement on the mainland.

Meanwhile, those who try to cling to Hong Kong’s old political coordinates will be rapidly surpassed. Regardless of whether they are pan-democrats, localists or something else, such positions will either be abandoned or transformed into something previously unrecognizable. It seems, by contrast, that the most accurate picture of the terrain has been grasped by the protestors who at first appear the most nihilistic—those who tear the bricks from the sidewalks of Argyle Street and scrawl “if we burn, you burn with us,” or “I’d rather be ashes than dust” onto the walls of flame-hollowed MTR stations. How is it possible that the least overtly political grouping—the one that seems to want nothing more than for the city to burn—is, in fact, the only one with an accurate intuition of the real political terrain? This is because, on the one hand, their very lack of political coordinates is itself an accurate reflection of the state of the movement’s collective consciousness. Their literal act of tearing apart the city is also a figurative unmaking of the city’s political and ideological foundation.

On the other hand, these young nihilists have a true grasp of both the necessity of power in political struggle as well as the fact that essentially all the existing powers are aligned against them and therefore need to be destroyed. Such a realization can of course develop into a reactionary, suicidal nihilism, which only wishes to see pain inflicted on others and, for the sake of this, is capable of accepting the logic of terrorism, total war and extermination of the enemy. But, at its core, this nihilism is in fact the seed of an accurate understanding of the global economic terrain which underlies the mirage of geopolitics. It is the realization that there is no way to “save” Hong Kong, because Hong Kong as it currently exists can only survive within a global capitalist system with China at its center. They recognize that whatever kind of Hong Kong everyone thinks they’re fighting for is already dead. The real question is not how to save it, then, but instead what sort of spaces they themselves will build on the sand beneath the paving stones. Maybe Hong Kong is not the name of a city slowly being killed. Maybe it is instead the name of a city that has not yet been built.

Notes

[i] For more detail on the role of the Japanese crisis in regional economic development, see our economic history of the era: “Red Dust: The Transition to Capitalism in China,” Chuang, Issue 2, 2019. <https://chuangcn.org/journal/two/red-dust>

French translation: https://dndf.org/?p=18246

Portuguese translation: https://coletivoponte.noblogs.org/post/2020/01/06/o-deus-dividido

”Hong Kong: a struggle for bourgeois freedoms trapped within the limits of capitalism and political submission to us/uk imperialism’:

https://mouvement-communiste.com/documents/MC/Letters/LTMC1947ENvF.pdf

Chinese translation from Reignite (壞火)

分裂的天神——給香港的一封信

https://www.reignitepress.com/post/divided-god

Revised Chinese translation:

身体分裂的神灵:致香港的一封信

https://chuangcn.org/2020/06/divided-zh/