Overview: Faultlines

These international crises would soon create an opening for the incorporation of China into global circuits of accumulation. But this would only be made possible after a series of deep faultlines that had cut across both the developmental regime and the socialist bloc more generally finally fissured, throwing China into alliance with the opposing camp in the course of the Cold War. In this section, we detail the nature of these building crises and explain how, exactly, a developmental regime that had stalled the transition to capitalism could ultimately become a vehicle for that very transition. We dig deeply into the evidence detailing these crises and the various makeshift attempts to solve them, and at various points it may be easy to lose sight of the larger theoretical picture. But these bigger questions are actually the heart of the story.

Central to these theoretical concerns is the question of the transition from pre-existing societies into a capitalist mode of production. Below, we emphasize both the nature of the capitalist system (in order to properly frame what a transition into it entails), and the various mechanisms that undergird the process. Our framework draws specifically from Marx’s understanding of capital’s logic and various debates among subsequent scholars informed by Marx concerning the history of capitalism, especially the “Brenner Debate” about the agrarian roots of capital in England. More generally, in order to understand the nature of change in industrial systems (which is both punctuated and gradual) we draw several important tools from the attempt to theorize large-scale systemic change within evolutionary theory, specifically as developed by Stephen Jay Gould. This story is not meant, however, to be an academic account, but instead a readable narrative that emphasizes historical processes rather than theories about them. We therefore do not pose this narrative in the meta-historical language of disembodied academic voices debating one another. Though obviously informed by these discussions, the names and egos of all scholars are largely confined to footnotes, where they can be properly subordinated to the masses of people who actually make history, rather than those who merely speak of it.

The history of the transition is complex, but major trends can be identified in retrospect. Below, we review the details of the developmental regime’s ossification and explain the early moves toward reform as makeshift responses to this deeper social and economic crisis. Central to this story is the problem of stagnant agricultural production and the slow growth of rural industry after the Great Leap. Moves to modernize agriculture, implement new green revolution technologies and funnel surplus rural labor into light industrial activity began to link together in a self-reinforcing dynamic that tended toward increasing marketization and greater dependence on outside inputs, which would open the door to increasing economic ties with the capitalist world. This was all occurring, meanwhile, in the midst of deeper crises within the socialist bloc. As tensions between China and the Soviet Union grew, the developmental regime lost its most important source of imports and technical training just as it was brought to the brink of war on all fronts. This led to a period of isolation that exacerbated the autarchy and ossification of the late developmental regime, ultimately deepening the crisis and forcing the state to look elsewhere for key external inputs. It was in this context that the diplomatic rapprochement between China and the United States took place, pivoting the course of the Cold War and laying the groundwork for a possible (but at that point far from certain) entry of China into the capitalist economy.

Though the main events in this story are fairly straightforward, we take a different approach to its retelling. We emphasize, first and foremost, that policy decisions and the strategies of statesmen largely follow from more fundamental historical conditions, produced by systemic dynamics, including inertia, on the one hand, and the momentum of masses of people, on the other. Great leaders are not the authors of history, but merely annotate and offer minor edits. Just as we argued, then, that the socialist era was not “Mao’s China,” we maintain that the period of transition in no way belonged to Deng Xiaoping. The “Reform and Opening” (改革开放) was never a systematic strategy for marketization. In fact, it was never even a coherent strategy. Its narration as such has taken place only years later, as a congratulatory story meant to uphold the mandate of the state. In reality, it was a haphazard and makeshift process, utterly contingent and often extremely uncontrolled. This also means that the transition could not have been the result of a “betrayal” undertaken by one faction within the party. Even if such a conspiracy were to have existed, the balkanization of production and the ossification of the state machinery would have ensured that it could never be carried out. Instead, all the major reforms tended to be after-the-fact official stamps given to much more local experiments.

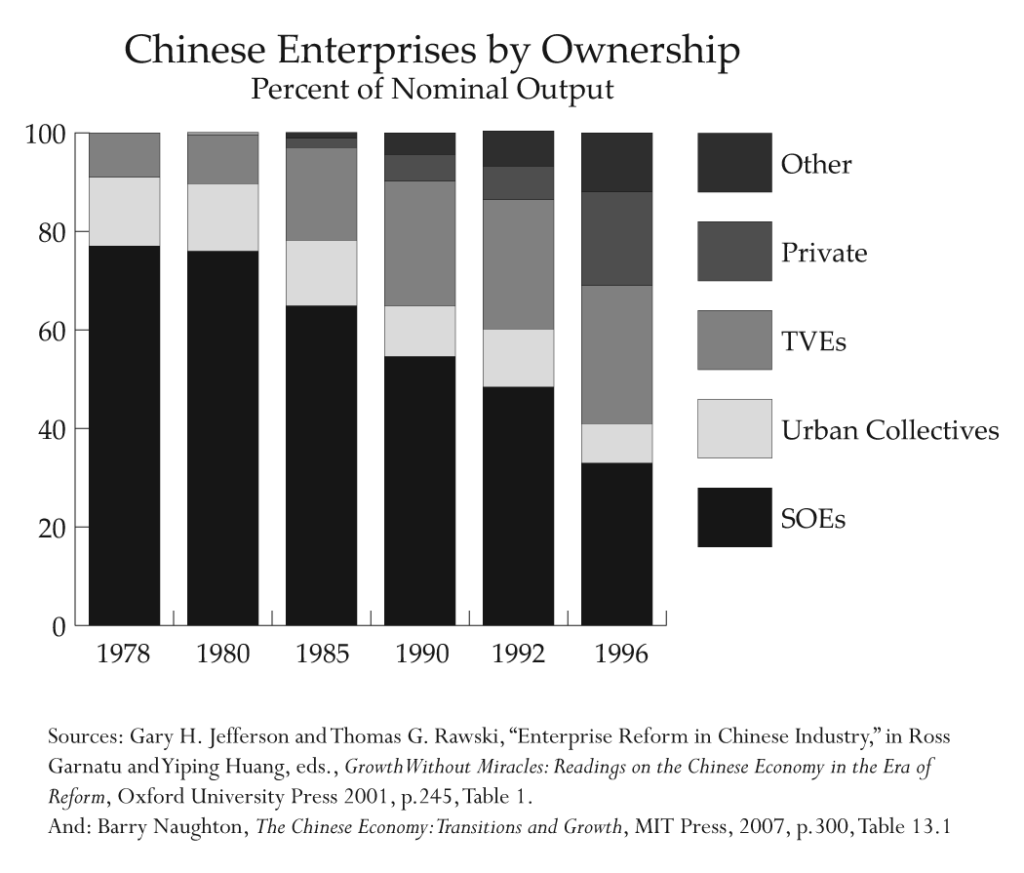

Secondly, we maintain that China’s developmental regime was not able to cohere as a true mode of production, nor was it a “state capitalist” or a “bureaucratic capitalist” country. The attempt to adorn capitalism with adjectives is simply a smokescreen obscuring a poor understanding of its fundamental dynamics. And the socialist developmental regime was not capitalist. Those who argue that the end result of the transition somehow proves the pre-existing capitalist essence of the socialist era make a bizarre logical presumption that would hardly be tolerated in any discipline outside theology: conflating the ultimate end of a process with its preceding forms, as if the germ of the human species were present at the dawn of life. Instead, we offer a theory of how a developmental regime that was not a mode of production slowly broke down, overtaken by the self-reinforcing dynamics of marketization that would ultimately cohere into a mode of production ruled by the law of value.

Finally, we neither claim that capitalism was a wholly domestic product, generated by the unleashed entrepreneurial energies of the peasantry, nor a wholly invasive system, forced upon China by an alliance between local bureaucrats and the international bourgeoisie. It’s true that the law of value had begun its gestation in the Chinese countryside, and specifically within rural industry. In the cities, a proto-proletariat had already taken shape, and even the largest state-owned enterprises had begun to market some of their products and, most importantly, to subcontract work to smaller urban and rural industrial firms largely operating within the market. But strong non-market forces also existed, shielding agriculture and protecting the privileges of the state industrial sector well into the new millennium. The development of this domestic law of value could only be completed by the simultaneous incursion of the global economy in the form of imported capital equipment, increasing the state deficit, and the newly opened zones for export. This export economy and the capital networks that drove it are the subject of the subsequent section.

The Geography of Capitalist Accumulation

The global conditions outlined above would soon converge with a domestic crisis in the Chinese developmental regime. Before detailing this domestic crisis, however, it will be helpful to outline the laws of motion that determine the geography of production under capitalism. The compounding accumulation of value is accompanied by spatial expansion. At an abstract level, the basic logic of capitalist production has, from its inception, had a global character: it has oriented itself as if it were a global system, even when its actual productive infrastructure was geographically delimited. But the subsumption of the Asian Pacific Rim, begun in Japan and completed by the transition in China, would for the first time see the majority of the world’s population subject to the direct rule of capital.

Though often formulated in the abstract, with an emphasis on its ability to reshape and domesticate culture, society and the non-human world, the material community of capital is first and foremost defined by its ability to reshape territory to suit its needs. On one end, this entails the systematic destruction of non-market subsistence, and the perpetual maintenance of various, seemingly extra-economic systems that prevent such subsistence from again becoming possible. Of these, property law is the most obvious, but equally important is the “historical and moral element” that enters into the determination of the value of labor-power, signaling the various ways that the material community restructures the fundamental components of human existence, thereby domesticating humanity in accord with the inhuman imperative of accumulation.

On the other end, however, the expansion of the material community also entails the construction of entirely new sorts of territories, such as the logistics complexes that defined the shift of capital across the Pacific Rim. The exact character of these territorial-industrial complexes has changed in each expansionary wave, but their defining feature is one of spatial inequality. Capitalist production is defined by the extreme geographical concentration of industry. Paired with the destruction and continual prevention of alternative forms of subsistence, this results in rapid urbanization, and cities themselves are severed from their historic limits of climate, geography and soil fertility. The archipelago of logistics infrastructure encircling the Pacific Rim was therefore a sort of vanguard of global capitalist production, pushed eastward by declining profitability in the world economy and by the geopolitical calculations of the United States, as the reigning hegemonic power tasked with addressing this crisis. As we detail above, the import of advanced capital goods from the US, Europe and, later, Japan triggered a series of economic booms in the region, facilitated by wartime expenditures in a series of anti-communist conflicts. While many of these wars were either lost (as in Indochina) or reached a stalemate (as in Korea), it was ultimately their economic side-effects that would breach the divide between the capitalist and socialist blocs.

The Countryside in the Socialist Developmental Regime

Returning now to the domestic situation, it will be helpful to start by reviewing the general conditions of the socialist developmental regime as we left it at the close of “Sorghum & Steel.” This regime was not a mode of production because it never developed an internal logic capable of reproducing itself independently from continuous managerial oversight. This meant that it could not sustain itself at the social scale, resulting in a balkanization of society defined by the borders between autarkic production units. It also meant that the regime could not reliably ensure its reproduction over time, leading to rapid ossification. Nonetheless, in the course of this ossification the developmental regime did form its own local class structure, defined first by the extraction of grain from the countryside and, second, by proximity to the central organs of the state. This class structure was inherently contingent on the character of the developmental regime, and was therefore both chaotic and doomed to rapid obsolescence.

The rural-urban divide defined the developmental regime and was regulated by a high accumulation rate, in which consumption was kept low so that investments in heavy industry particular could be kept high. The increase in consumption was consistently kept below the GDP growth rate, so that industry’s share of GDP rose from 25.9 percent of GDP during the First Five Year Plan (FYP), begun in 1953, to 43.2 percent by the end of the Fourth FYP in 1975.[1] Another way to look at this is that, although over 80 percent of the population worked in agriculture, that sector received less than 10 percent of investment over three decades, from 1953 to 1985,[2] while 45 percent went to heavy industry over the same period.[3] Agriculture fed industry. As a percentage of GDP, industry had already surpassed agriculture by the late 1960s. This strategy would begin to shift with the reforms of the early 1980s, however, when the rate of consumption was allowed to rise, slowing the industrialization process.[4] In this sense, industrialization’s relationship to agriculture was quite different in China than it was in the Soviet Union, which had a far higher per capita grain production in the 1920s and 1930s than China had in the 1950s.[5] Thus, while the Chinese state attempted to rapidly develop heavy industry, agricultural production remained a much more severe limit on industrialization. The state had to increase both its relative share of agricultural surplus as well as its overall agricultural output.

The land reform undertaken in the first years of the developmental regime removed the main rural consumer capable of competing with the state for agricultural surplus: the rural elite (including landlords, local officials, merchants and relatively well-off peasants). In late 1953, the state put in place a mechanism to extract this surplus. Called “unified purchasing and marketing” (统购统销), the system entailed complete state control over the grain market, squeezing out all private merchants. This was seen as the best of several imperfect options at the time, necessary if the developmental regime were to remain independent from a postwar global market firmly in the hands of the United States. As Chen Yun, who sat on the drafting committee of the first FYP, explained the logic behind state control over grain at the time: “Are there shortcomings? Yes. It might dampen production enthusiasm, hound people to death […] and cause insurrections in certain areas. But it would be worse if we do not implement it. That would mean going down the old road of old China importing grain.”[6] After the implementation of the state monopoly, political debates between 1955 and 1980 shifted to the question of how to develop agricultural production in order to produce a larger surplus. Of particular importance was how to avoid the risk of reigniting a local transition to capitalism via the development of rural markets.

The Great Leap Forward (GLF) of 1958-1961 was one attempt to answer this question. Self-reliance and the mobilization of rural surplus labor (focusing particularly on slack season labor, but also inefficiently utilized reproductive labor) would make up for the lack of state investment in agricultural production through collective participation in agricultural capital construction. Meanwhile, this would allow for a high accumulation rate, without risking a revival of rural markets. Such a developmental policy relied on large-scale, rapid collectivization, egalitarianism, successful rural industrialization, and political motivation. On many of these accounts, the attempt was a clear failure. Conversely, a policy of agricultural modernization that relied on more substantial investment from the state, creating the conditions for scientific, mechanized, large-scale farming was another option. Yet this would initially slow the industrialization process, as state investment in agriculture would be much higher, constraining the funds available for heavy industry. Ultimately, the pressure to rapidly industrialize within the context of an often hot Cold War pushed the leadership in this former direction, though not without disagreements.

Gender and Rural Industry in the Great Leap

Changes in rural industry over time provide an important lens for observing shifts in China’s economy as a whole. In the late imperial economy, rural handicrafts such as textiles and papermaking generally functioned as an “organic link between growing and processing agricultural product.”[7] Handicraft production coupled peasant households or lineage “patricorporations”[8] with local and regional networks of consumers via an expansive system of “market-towns.” The nineteenth century onslaught of imperialist invasions, bringing the capitalist world market and a century of civil wars in tow, disrupted this system profoundly, but not terminally.

At the dawn of the developmental regime in 1949, the output value of rural “sideline production” (mainly traditional handicrafts) totaled 1.16 billion yuan in 1957 prices.[9] The land reform movement helped such industries recover somewhat and even grow on a household basis, with over ten million peasants working part time in commercial handicrafts as of 1954, yielding an almost-doubled output worth 2.2 billion yuan. The 1953 introduction of the unified purchasing and marketing system severed these sidelines’ “organic link” between farming and the marketing of processed agricultural products, causing rural incomes to fall in areas that had specialized in handicraft production.[10] When the state established monopsony over agricultural products, rural processing businesses were inevitably cut off from their supplies. Grain, cotton, silk, peanuts, and soybeans—the staple supplies of nonagricultural businesses—were taken by the state immediately after the harvest. In fact, during the 1950s the countryside became deindustrialized.[11]

In 1955, the cooperative movement began organizing handicrafts into “sideline production teams” (副业生产队) under the agricultural co-ops. At first, the movement’s emphasis on agriculture further damaged the situation of sideline industries, with virtually all manufacturing taken over by state enterprises, but by the end of 1957 rural industry had recovered to just above 1954’s output value, equaling 4.3 percent of that year’s agricultural output.[12] Then in 1958, the Great Leap Forward incorporated and reorganized both these village-based sideline production teams and over 30,000 town-based handicraft co-ops under “Commune and Brigade Enterprises” (CBEs). Those CBEs that survived into the 1980s would go on to become “Township and Village Enterprises” (TVEs). In a prime example of capitalist exaption of socialist institutions, the CBEs would pass from being a central component of the GLF’s envisioned “transition to communism” to becoming the first private enterprises and a key vehicle of the transition to capitalism. But even prior to that watershed, CBEs would undergo several earlier changes reflecting shifts in national economic policy.

The creation of the CBEs marked the state’s first systematic attempt to promote rural industry as such. If handicrafts had previously intertwined peasant familial economies with local and regional markets through the processing of agricultural goods, the CBEs fundamentally transformed rural industry by making it subservient to the changing dictates of state policy—policy that was responding in turn to changing international conditions. Initially, during the GLF, this centered on diverting “surplus” rural labor from agriculture to contribute directly to the national race to “surpass Britain and catch up with the US” in heavy industries such as steel. This was coupled with the goal of establishing a self-reliant alternative to the import of capital goods for agricultural modernization, now that tensions with the USSR were complicating the latter, more conventional strategy. This second goal would rise to the forefront after the first was abandoned along with the GLF as a whole in 1961.[13]

In practice the diversion of “surplus labor” into non-agricultural production meant transferring primarily young male peasants from the fields into the 7.5 million new factories set up in 1958 and, more commonly, into the hills where they built roads, brought new land under cultivation, laid railroad tracks, and dug mines and irrigation ditches.[14] And by the end of 1958, the newly established CBEs already employed 18 million people, yielding about three times as much output in 1958 as they had in 1954, and almost five times by the following year.[15] As a result, agricultural labor as a percentage of total rural labor dropped from between 90 and 93 percent in the early to mid-1950s to 71 percent in 1958.[16] This sudden transfer of primarily male rural labor into non-agricultural activities was made possible by pulling women out of the home to become the main source of agricultural labor, reversing the traditional gendered division that had prevailed for centuries, memorialized in the phrase “men till while the women weave” (男耕女织). At first, this reversal was facilitated by the socialization of some of the reproductive work that women would otherwise have done at home in addition to farming. The newly established, village-sized “production brigades” set up public dining halls, facilities to care for children and the elderly, and “other collective welfare measures to emancipate women from the drudgery of the kitchen, and presently men and women began to receive wages for their labor, supplemented by free supply of such items as rice, oil, salt, soya sauce, vinegar and vegetables,” along with free clothing, medicine, child-delivery, and even haircuts.[17]

Such experiments did not really challenge the gendered division of labor as such, since this socialized reproductive labor was mainly performed by elderly women, but it did free up younger women to spend more time doing farmwork for the collective. This brief arrangement collapsed when the famine hit and many institutions of the GLF were dismantled, including both these facilities for socialized reproductive work and most of the CBEs. Henceforth, young women were expected to shoulder the double burden of collective farmwork, for which they received fewer workpoints than men, and domestic work in the household, which now became unremunerated and invisible. Ironically, then, this experiment aimed partially (in rhetoric, at least) at decreasing the disparities between gender roles, between the city and the countryside and between industry and agriculture actually ended up imposing modern versions of those distinctions upon rural society for the first time. The original socialist goal of reducing and ultimately eliminating all gendered disparities and even the family itself was definitively abandoned: “Women’s handicraft labor, which had brought in money for the household in earlier times, was now more invisible than ever,” and this invisible, unpaid labor became “foundational to the state accumulation strategy.”[18]

As famine ravaged the country for three years starting in 1959, central leaders identified not only public dining halls and backyard steel furnaces but also the turn toward non-agricultural activities in general as the essential causes of the disaster, rather than the state’s continued seizure of grain and its export to the USSR even after the famine had become apparent. In 1960, the Eighth Central Committee began a series of calls to close most existing CBEs and prohibit the opening of new ones. Their number fell from 117,000 in 1960 to 11,000 in 1963,[19] and the percentage of the national workforce employed outside of agriculture dropped even lower than it had been in 1957.[20] As a percentage of total rural labor, agricultural work rose from 71 percent in 1958 to 97 in 1962, remaining between 96 and 97 percent until 1973.[21] This nearly decade-long reversal of rural industrialization obtained stable policy articulation in the Tenth Plenum’s “Sixty Articles” (“Regulations on the Work of the Rural People’s Communes”) of 1961-1962, which stated, “The commune administrative committees shall generally not run new enterprises for years to come.” Another Central Committee announcement two months later went further by prohibiting communes and brigades from establishing not only new enterprises but also any new sideline teams.[22] Despite this, CBEs would gradually recover throughout the decade, and by 1970 were ready to receive a sudden push—this time with an exclusive focus on agricultural modernization.

Fraught Efforts at Agricultural Recovery

By the early 1960s, the subsistence situation was grave, and the focus was on reviving agricultural production. Without raising state agricultural investment, however, the only way to increase agricultural production was to intensify labor inputs. While the more flexible, post-Leap organizational form of the commune and rising rural population brought increased labor inputs and higher per-acre yields, agricultural labor productivity rose only very slowly until the late 1970s, when state investment in agriculture finally began to increase significantly. In the 1960s and 1970s, in other words, agricultural modernization was again postponed as a future goal, too costly during a time of rising tensions with the Soviet Union, when rapid industrialization—and therefore a focus on industrial investment—was seen as a strategic necessity. Throughout this period, various methods of encouraging greater rural labor investments were attempted via both local experimentation and central state policy. Each form was at best only temporarily successful, as discussed in “Sorghum and Steel.” This process began with the state attempting to rebuild the basic rural institutional structure that had broken down in the Great Leap Forward.

In 1961 and 1962, a new commune structure was adopted. With accounting at the commune level during the Leap, it was difficult for anyone to see how their own work affected their consumption. Communes held tens of thousands of people comprising many villages. The post-Leap structure, by contrast, reduced the importance of the commune in organizing production. The lower levels of the production brigade (the size of a village and containing up to a couple thousand people) and the production team (usually containing between 25 and 40 households) became the center of decision-making about production. Under this new system, communes would act as a “union” of brigades, needing agreements from the lower levels to undertake large projects. Brigades would be responsible for collective profits and losses and would now act as the basic “owner” of rural land. But brigades were also not supposed to enforce egalitarianism among the production teams below them. Brigades had to bargain with their teams for resources and in order to undertake collective projects, and teams could refuse labor to the brigade and above. The team became the basic level of accounting, planning production and small-scale capital construction, deciding remuneration rates, and managing agricultural machinery. Overall, this amounted to an attempt to stop the rapid disintegration of rural institutions following the Leap. At the time, the shift to teams as the basic level of accounting was seen as temporary. The now-postponed, longer-term goal of agricultural modernization implied an increase in the scale of production and organization of labor. Debates about when to raise the level of accounting back to the brigade repeatedly flared up within the party leadership, but they failed to have an effect in most areas due to lack of support.[23]

After two years of sharp declines in agricultural production (1959 and 1960), agriculture began to grow again from 1961, when state agricultural purchasing prices were raised by well over twenty percent, incentivizing labor investments. Yet from the early 1960s through to the late 1970s, one system of labor remuneration after another was tried in order to maintain the intense labor inputs necessary to raise yields. With a policy of local self-reliance remaining strong throughout the 1960s and early 1970s at the expense of agricultural modernization, however, state investment in agriculture and farmland capital construction remained largely stagnant, 1964 being the only year with a significant increase in investment. The mobilization of labor together with new seed varieties did result in relatively high agricultural growth rates between 1962 and 1966,[24] but this growth was not sustained through the late 1960s, with 1968 actually recording a decline. Nor did labor productivity increase significantly throughout this period.

Popularized in the early to mid-1960s, indigenous green revolution technologies, especially new seed varieties and hybrid rice plants, gave a boost to agricultural production, but they also necessitated greater chemical inputs, especially fertilizers, which were still in short supply. By the early 1970s, many of the initial benefits of new seeds began to wear off. It was only with significantly increased state agricultural investments at the end of the 1970s that such technologies really began to pay dividends. Likewise, egalitarian systems of remuneration had begun to show signs of strain as well. Village studies show that monthly meetings to decide remuneration by the use of workpoints began to be taken less seriously, and workpoints that had been decided by group assessment now became almost a set wage as peasants no longer came to meetings. The effects of ideological motivation, so crucial to the socialist developmental regime, were waning. The quality and intensity of work suffered, as did yields.

Falling growth rates from the late 1960s into the early 1970s led to rapid shifts in rural policy, as the state looked for ways to increase agricultural production without raising state investments dramatically. While the production of agricultural chemicals, in particular fertilizers, grew in the 1970s, its sharpest growth did not come until the end of the decade. All of these problems led to a slow and uneven process of agricultural modernization in the 1970s, with absolute agricultural production suffering as a result. National grain production grew unevenly from 240 million tons in 1971 to 284 million in 1975, then it stagnated for the next two years.[25] It wasn’t until after Mao’s death in 1976 that agricultural policy took on a much clearer direction, as discussed below, reacting to the stagnation of the mid-1970s.

Rural Industry after the Leap

Despite the mass closure of CBEs and the restrictions that the Tenth Plenum had imposed after the famine, rural industry began a gradual recovery in 1964, now with a more exclusive focus on industries serving the increasingly necessary but still de-prioritized goal of agricultural modernization—with the idea that rural enterprises could play this role instead of state-run enterprises, which were to remain focused on heavy industry. On the one hand, this reflected an increasing recognition that the mere rearrangement of labor, combined with ideological mobilization, was losing its ability to increase agricultural output (especially now that many peasants had lost faith in the party following the failure of the GLF). On the other, the import of capital goods for agricultural modernization had now become nearly impossible, given the deterioration of China’s relations with the USSR and its allies. The hostile international environment also meant it would be risky to rely on China’s few existing industrial centers for this task, as they either abutted the border with the Soviet Union or sat along the coast, where they were susceptible to US military power. The solution that emerged was a specific form of rural industrialization: the combination of (a) the “Third Front” strategy of establishing new bases for heavy industry scattered throughout China’s underdeveloped southwestern provinces and (b) the revival and expansion of CBEs and county-level state enterprises producing modern agricultural inputs and machinery along with cement, iron and energy. The latter, in particular, would help to create the conditions for marketization in the countryside, prefiguring the rapid rural industrialization of subsequent decades.

This second round of CBE development started gradually, as fears receded about the association between famine and the promotion of rural industry. In 1964 (the same year the Third Front was launched), the Central Committee formulated a policy of promoting the “the five small industries” (五小工业) deemed crucial to agricultural modernization: power (small coal mines and hydroelectric plants), small iron and steel mills, small fertilizer plants, small cement plants and small factories producing agricultural machinery.[26] At first, three of these “five smalls” (steel, fertilizer and cement) were limited to enterprises operated at the county level, that being the lowest level of the state apparatus whose officials were directly appointed by the central government. The other two “small industries” could also be operated at the commune level, but none could be operated at the still lower brigade or team levels. This was the first time since the GLF that rural governments were authorized to set up their own independent sectors of industry.[27]

It would not be until 1970, however, that the Fourth FYP would clearly shift emphasis to both the commune and brigade levels, promoting the development of CBEs in all five of the “five smalls.” This outline was fleshed out at that year’s North China Agricultural Conference and the following year’s National Conference on Rural Mechanization, which declared that “a key purpose in developing rural industry was to further the cause of agricultural mechanization over a ten year period and which made rural industry eligible for bank loans and fiscal support.”[28] It was now also emphasized that the five smalls should operate according to the principle of “the three locals” (三就地): the use of local inputs, on-site production, and the sale of output to local markets. This national policy direction was then given a boost by some underdeveloped provinces such as Hunan, which immediately launched a campaign called “Construct an Industrialized Province within Ten Years” and, in 1972, established a provincial bureau specifically for supporting CBEs.[29] By the end of that year, CBEs had surpassed county-level enterprises to become the major engine of rural industrialization throughout China. CBE output value grew from 9.25 billion yuan in 1970 to 27.2 billion in 1976, averaging 25.7 percent per year.[30] By 1978, nearly half of China’s industrial workforce would be employed by rural enterprises at either the county, commune or brigade level.[31]

Aside from the dire international situation and the persistent problem of stagnant output, another factor contributing to the expansion of CBEs around 1970 was the Cultural Revolution. The mass struggles of 1967-1968 seriously disrupted urban production in many parts of China, creating demand for certain CBE-produced goods. Cadres in some communes near big cities took the initiative of retooling CBE production to serve neighboring urban markets when their own production was strangled by strikes and constant political mobilization.[32] Then, from 1968 onward many urban cadres, workers and technicians began to be “sent down” to the countryside, all contributing to CBE development.[33] Meanwhile, changes in the local investment structure undergirded these changes. All this would have come to nothing, for example, if the new CBEs did not receive generous financing from local banks—at the time all technically branches of the People’s Bank of China or, in some cases, local co-operative savings institutions that didn’t take personal deposits. In Sichuan’s Mianyang Prefecture, for example, “lending to collective industries increased by 58 percent in 1970, and by a further 75 percent in 1971; between 1969 and 1978, the total increase in lending was 5.7 fold.”[34] This in turn was made possible by China’s financial decentralization in the early 1970s, which gradually began to mimic market allocations of investment funds in some rural areas.[35]

Despite these national and sometimes provincial pushes, the lingering association of rural industry in general and CBEs in particular with the famine stalled their development in many locales. This was especially true in Sichuan and Anhui, the two provinces hit hardest by the famine. They did not recover the CBE output level of the Leap years until as late as 1978 and 1980, respectively.[36] By contrast, most provinces regained their 1958 peak by the late 1960s, even before the national push launched in 1970. In fact, commune enterprises grew at a national average of 16 percent between 1962 and 1971—even higher than China’s 11 percent overall rate of industrial growth.[37] This means that local cadres were taking the initiative to support such enterprises despite the central government’s restrictions. Up until 1978, however, the state officially continued to prohibit both communes and brigades from engaging in most industries, and “any commune discovered engaging in industry on more than a commune scale was penalised.”[38] One rural cadre in Sichuan reports being punished for starting a commune-level brick kiln in the late 1960s, and being repeatedly denied loans and authorization for operating the commune’s few enterprises that had survived the Great Leap.[39] Official policy had now clearly begun to diverge from the reality of industrial growth, contributing to the massive shift in rural policy that would begin in 1978.

Class and Crisis in the Late Developmental Regime

Over the course of the 1960s and ‘70s, the developmental gap between China and many neighboring countries had begun to widen. Overall, after the GLF, the socialist developmental regime was able to secure only stalling bursts of growth and marginal improvements in general livelihood. Primary education and access to basic healthcare unarguably improved throughout this period, but these victories were won against a backdrop of pervasive stagnation. Incomes essentially plateaued in both city and countryside—whether measured by wages, estimates of wages plus non-wage subsidies or simply calorie consumption.[40] Meanwhile, urbanization halted entirely. Throughout the last two decades of the developmental regime, the population living in cities was held at under 20 percent of the total, only growing an average of 1.4 percent per year after around 1960, almost entirely due to natural increase.[41] But even this proved too much, as the demographic boom of the 1950s began to flood the saturated urban job market with a new generation looking for work. The result was a wave of layoffs and rustication programs during the Cultural Revolution that funneled even more people into rural and peri-urban areas.

The class structure of the developmental regime, shaped in the 1950s and hardened over the course of the following decade, was defined by the rural-urban divide between the peasant class of grain producers and the urban class of grain consumers. Urbanites were themselves subdivided according to their level of access to the grain surplus—which obviously translated into numerous, often substantial privileges aside from simply eating more—ordered via political status and employment in state-owned industrial enterprises of various sizes and importance. But by the middle of the 1970s, the class structure of the developmental regime had begun to strain. Industrial production continued to grow (despite a brief dip in the most tumultuous years of the Cultural Revolution), but the returns on this growth were funneled into even larger investment drives. In the countryside, an expansion of primary education and noticeable healthcare improvements (all facilitated by the rustification of skilled young urbanites) helped to suppress further unrest, but ruralites remained at the bottom of the developmental regime’s class system, with very little chance at upward mobility. In the cities, a loosening of restrictions on sideline production allowed foodgrain and meat consumption to increase somewhat, but incomes (including subsidies) stagnated. Despite pervasive autarky and geographic unevenness, the general pattern was an increase in the rural-urban divide throughout these decades, with the urban, grain-consuming class commanding incomes somewhere between three and six times that of grain-producing ruralites.[42]

Meanwhile, the black market had begun to grow as the state ossified and production became more militarized: the army had stepped in to directly administer industry after the unrest of 1969, and cadre numbers began to skyrocket as early as 1965. By 1980, the total number of cadre would reach a peak of 18 million, nearly 2 percent of the total population and 4 percent of the total labor force.[43] In the cities, the sub-divisions within the class of grain consumers multiplied alongside corruption, with cadres and even many state workers hoarding ration coupons, embezzling enterprise funds and running illegal private businesses on the side.[44] At the bottom of this urban hierarchy sat a growing proto-proletariat of lower-paid temporaries, returned rusticates, “worker-peasants,” “lane labor” and apprentices, all working precarious jobs at small collective firms subcontracting for the large state-owned enterprises. This proto-proletariat had grown to more than ten million by the 1970s, or about 3 percent of the total labor force. Such workers were disproportionately young and female, and largely concentrated in cities like Shanghai and Guangzhou, where they made up a much larger share.[45]

These later years of the developmental regime saw continuing decentralization and local autarky, combined with the Third Front investment drive initiated after the unrest of 1969. This investment drive was defined by its isolationist military logic: the emphasis was on construction of massive industrial projects in the mountainous regions of China’s interior provinces, the goal being to build an industrial structure secure from US military incursions along the coast and Soviet incursions along the land border to the north.[46] Though similar in size and character to the GLF, this new development burst did not divert unsustainable amounts of resources from the countryside, instead distributing austerity more evenly across the population. Wages stalled, material incentives (bonuses, piece-rates, etc.) were suppressed, and the autarkic nature of production meant that those in larger, better-equipped enterprises or more climatically sound rural collectives tended to fare better than others. Many popular images of quotidian life in the Cultural Revolution (and the socialist era more generally) derive from this period, when material incentives were replaced with ideological rewards (red scarves, pictures of Mao, copies of the Little Red Book) and scarcity was met with essentially spiritual exhortations to sacrifice for the building of socialism.

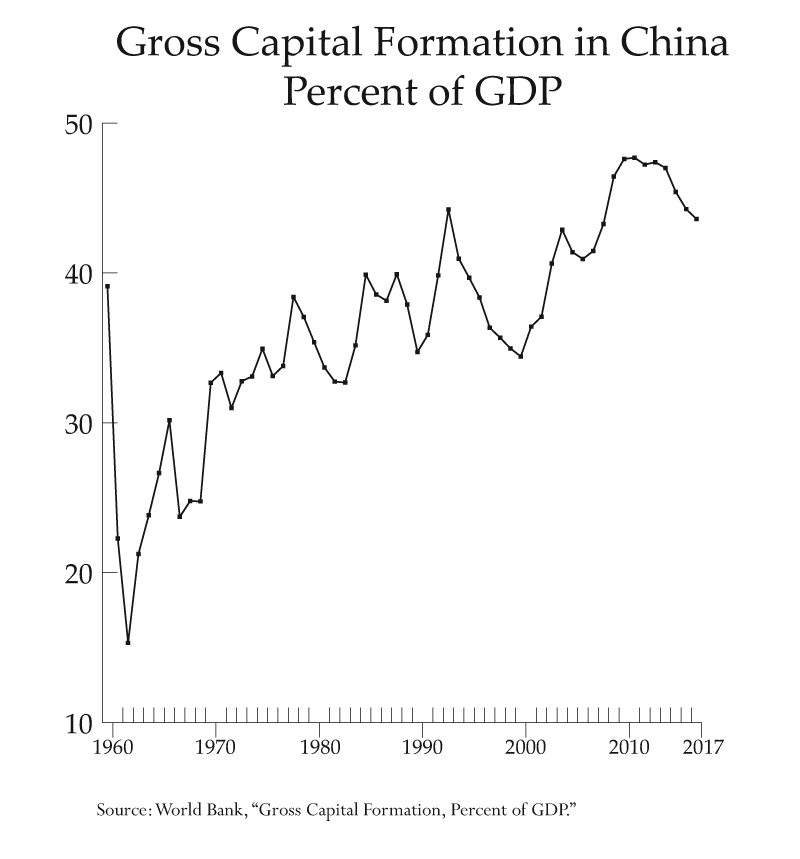

But scarcity in this era was markedly different than that experienced in the immediate aftermath of the GLF, where recovery was characterized by comparatively low levels of investment. Prior to the Leap, investment as a share of GDP had sat around 25 percent, and immediately afterward it troughed at a mere 15 percent. Following this, investment not only recovered, but would never again experience such a severe trough. Despite a brief dip during the Cultural Revolution, investment as a share of GDP has undergone a secular increase from the post-Leap trough to today.[47] Continual, expanding “big push” investment drives would become a central characteristic of Chinese development, continuing well after the socialist era. The need to sustain these drives in order to avoid the pitfalls of absolute scarcity experienced in the earlier years of the developmental regime would, in fact, provide one important justification for the opening of the economy.

Figure 2

Breaking the Bloc

As the postwar boom in the capitalist world gave way to the long downturn, a series of qualitatively different crises had spread throughout the socialist bloc. China’s developmental regime, though initially successful in preventing the transition to capitalism, was only capable of coordinating production and distribution through an increasingly ossified, militarized and zealous fusion of party, state and society. In other socialist countries, a similar decay had long been evident. The root of this decay has been among the most heated topics debated within Marxist scholarship, with polemics and counter-polemics spilled across nearly the entirety of the last century, often written by political factions stranded in the cold world that came after the insurrectionary era and therefore desperate to clothe themselves in the costumes of long-dead revolutions. There’s no need to repeat these debates, and our inquiry into this question as it relates to China has been made evident already.[48] Nonetheless, it is contextually important to note that this more general crisis of the socialist bloc passed through a certain watershed with the shifts in policy and popular activity that followed the death of Stalin in 1953. But in the same way that Chinese policy changes were often makeshift responses to specific crises and local limits to the developmental project, the conflicts within the socialist bloc that were beginning to peak were not in any direct way “caused” by Stalin’s death, nor were Khrushchev’s policy shifts a simple matter of political whim. Instead, both the popular revolts that followed (in East Germany in 1953, Hungary in 1956 and Czechoslovakia in 1968) and the reforms implemented by Khrushchev were responses to deep-seated crises that had long been building within individual countries and within the hierarchies built into the USSR and the bloc more broadly. In each instance, this process of bureaucratization, revolt, reform and, in some cases, collapse, was shaped by local conditions.

Each socialist nation, whether federated within the Soviet Union or sitting outside of it, would therefore experience this period of tumult in its own fashion. Nonetheless, the global scale of the Cold War helped to sculpt certain regional trends within this broader crisis. The two major geographical fronts of the war lay across Europe and along the Asian Pacific coastline, and these were the areas that would experience some of the harshest effects.[49] In Eastern Europe, treated as a military buffer between the Russian core of the USSR and the capitalist world, this came in the form of thorough domestic repression and widespread militarization of society, justified by the threat posed by NATO. These conditions, combined with the troubled histories of many countries’ incorporation into the socialist bloc, ultimately stoked a series of popular revolts that were met with more repression, a cycle that would culminate in the overthrow of most of the region’s national governments in 1989. Along the Pacific, however, the crisis was defined by open warfare on the Korean Peninsula and across Indochina, as well as continual guerilla war in the Philippines and repeated conflicts across the Taiwan Straits. While Russia was somewhat insulated, China had no such luxury.

The continuing active involvement of the United States in ongoing military conflicts bordering China led to a situation in which Chinese national imperatives had begun to contradict those of the USSR which, under Khrushchev, had started to lay the framework for a détente with the US as early as the late 1950s. Many of China’s critiques of the USSR in this period focus on elements of this détente, particularly the attempts to curtail the proliferation of nuclear weaponry via agreements such as the Partial Test Ban Treaty. By the end of the Great Leap, the USSR had ceased all material support for the Chinese nuclear program. This was despite the fact that the US had recently moved long-range nuclear missiles into Taiwan. But even if China could no longer secure military support from the USSR, its leadership could ensure that the interests of the Soviets and the Americans would not be united against it. Soon after, an artillery battle started by the Chinese initiated the Second Taiwan Straits Crisis, undercutting Khrushchev’s overtures for “peaceful cooperation,” and Chinese propaganda began to publicly emphasize the weakness of Khrushchev in the face of US imperialism, even while Chinese diplomats privately sought to secure talks with the US in the hopes of gaining formal acknowledgment (and thereby a seat on the UN, long held by Taiwan).[50]

Also involved in these conflicts, however, was an intentional strategy on the part of the US security apparatus to drive a wedge between the two major players in the socialist bloc. Well aware of the long-standing tensions between the Chinese and the Soviets, the new round of tensions would soon become an opportunity for the Nixon administration to pursue a triangular strategy of Cold War diplomacy that sought to trigger the increasingly volatile fault lines that had long divided the world’s two largest socialist countries. Over the course of the 1960s, these fault lines had already begun to buckle, and an increasingly autarkic China found itself faced with the prospect of simultaneous war against the world’s two great superpowers. By the end of the Cultural Revolution, the faults finally slipped, causing a tectonic shift within the socialist bloc that would ultimately define the shape of the second half of the Cold War.

Though sparked by the death of Stalin and the subsequent policies pursued by Khrushchev in the USSR, all driven by local processes of ossification, the historical roots of what would come to be known as the “Sino-Soviet Split” lay much deeper. Fundamental disagreements on theory, tactics and revolutionary strategy had existed between the CCP and the Soviet Union since the 1920s, when the Comintern-backed strategy of allying with Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Party had resulted in a disastrous period of white terror that very nearly extinguished the revolutionary movement. It was in these years (beginning with the Shanghai massacre of 1927) that the leadership of the CCP had shifted decisively from the party’s orthodox, urban wing, represented by the Soviet-educated “28 Bolsheviks” to its more populist, peasant-oriented wing, represented by Mao. Though maintaining strong relations with the USSR throughout decades of foreign invasion, civil war and reconstruction, these years of white terror had both ensured the CCP’s rural turn and made it wary of overreliance on Soviet guidance.

Nonetheless, Soviet aid had become integral to the early years of the developmental regime, particularly in the Manchurian industrial complex, which saw a massive influx of Russian technicians, managers and engineers in the early 1950s. As tensions increased after 1956, this flow of aid and skill-sharing slowed to a trickle. By the end of the 1960s, it had dried up entirely. Isolated from both the socialist and capitalist blocs, the domestic economy grew increasingly autarkic. This situation was portrayed in domestic propaganda as a proud form of self-reliance, simultaneously anti-imperialist and opposed to the bureaucratic ossification of the Soviet Union. In reality, autarky was paired with a volatile international policy that resulted in support for brutal governments such as the Khmer Rouge and a series of risky military engagements in neighboring countries such as India in 1962.

The most definitive of these was the 1969 Zhenbao Island Incident, a seven-month period of open (though undeclared) military conflict between China and the USSR. This conflict essentially condensed the previous decade of declining economic relations and political controversy into a single symbol of open hostility. Its exact cause (a border dispute over a patch of land in the middle of a river) was not particularly important, nor, in retrospect, was its conclusion (maybe a hundred or so dead soldiers on both sides, no solution to the border question, and an inconclusive ceasefire). What was important was the scale assumed by the crisis, clearly signaling that more was at stake than a few simple tracts of land. Though initiated by a sequence of attacks and counterattacks on Zhenbao Island, located in the Ussuri (Wusili) River, the official border between Russia and China in western Heilongjiang, the conflict would soon see an unprecedented military build-up along the entirety of the two countries’ 4,380 km border. The fighting in Heilongjiang had not only reignited simmering disagreements in the Northeast, but also raised a number of latent border issues and ethnic tensions in Xinjiang, abutting the Soviet Republics of Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan. In reality, the border had never been well-demarcated in the first place, both revolutionary regimes inheriting long-disputed territories defined by century-old treaties signed by the Tsarist and Qing states. China’s far west was particularly amorphous, only fully incorporated into the Qing in 1884 after more than a century of intermittent warfare. It was an ethnically diverse region, the majority of its population drawn from an array of Turkic-speaking nomadic steppe tribes, many of which held strong ties on both sides of the border.

When the Zhenbao Island Incident ignited a simmering border conflict in the Pamir Mountains, in Southern Xinjiang, bordering Tajikistan, the Soviets were able to use these long-standing ethnic tensions in the area to their advantage. Military build-up along the border had been occurring since failed border talks in 1964:

In 1965 the Soviets had 14 combat divisions along the border, only 2 of which were combat-ready; by 1969, Soviet forces had increased to between 27 and 34 divisions in the border areas (about half of which were combat-ready), totaling 270,000-290,000 men.[51]

Alongside this, the Soviets threatened to stoke a separatist insurrection within China, all backed by the possibility of nuclear conflict. As early as 1967, the USSR had deployed a long-range mobile nuclear platform to the border, within striking distance of China’s own nascent nuclear program, which used the Lop Nur desert in Xinjiang for testing. The same year had seen the detonation of China’s first hydrogen bomb at Lop Nur, and by 1969 the Russians would begin contemplating the idea of a joint strike with the US to eliminate China’s nuclear capacity. The Chinese, meanwhile, saw the Soviet Union’s nuclear parity with the United States as a threat to national security, since China was now dependent on being included within the “umbrella” of Soviet deterrence at the very moment when relations between the two states had become increasingly volatile. In 1968, the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia set a concerning precedent, with the “Brezhnev Doctrine” arguing that the USSR had the right to intervene in other socialist countries if necessary.[52]

Faced with these threats, the Chinese military turned to a strategy of “active defense,” defined by small-scale ambush attacks along the border, justified as last-resort defensive actions meant to deter future aggression.[53] It was just such an ambush that ignited the Zhenbao Island Incident in early 1969. The USSR perceived the attacks to be simple acts of aggression, rather than an attempt at defensive deterrence—the very logic of “active defense” symbolic of the increasing unpredictability of Chinese military policy. The same year saw the height of the Cultural Revolution, capped by dissension within the ranks of the PLA, and the risk of civil war. By the spring, the conflict over Zhenbao had escalated to involve thousands of troops and by the end of summer a similarly violent battle had taken place in Tielieketi in Xinjiang, along the border with Kazakhstan. Throughout, the Soviets had been threatening nuclear action against China, and the growing tensions began to risk the real possibility of a widespread nuclear conflict for the first time since the conclusion of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Official war preparations in China began in August, including renewed military mobilization and the formulation of plans for the mass evacuation of major cities.[54]

China’s counter to the threat of nuclear conflict was a “people’s war,” to be conducted via an overland invasion of the Soviet Union. Though technologically inferior, with only a handful of deployable nukes, the bulk of the Chinese threat came through the sheer size of its military, capable of flooding into the USSR and fighting a protracted conflict at home and abroad. The relatively low levels of urbanization within China also muted the threat of nuclear conflict itself—with a decentralized population, nuclear strikes on key urban centers would not have the same crippling effect as in Europe or the United States. The Soviets had no good plan to deal with such a threat. If war were to break out, key strategic centers in the Russian East could be lost to the invasion, and the Trans-Siberian railroad easily crippled. At one point, the idea of deploying nuclear mines along the border was considered, though Soviet military strategists understood, in the end, that any substantial nuclear attack would risk a world war.[55] The conflict was resolved inconclusively, ending as haphazardly as it had begun.

Triangles

Though the threat of open war with the USSR ultimately subsided, the militarization of the developmental regime did not. The risk of the war itself offered a justification for the disbanding of the more radical Cultural Revolution organizations, a process capped by the use of the military to quell the factional battles that flared into local armed conflicts in 1968 to 1969. Meanwhile, in order to ensure uninterrupted production, much of the country’s industrial infrastructure was turned over to military administration.[56] Domestically, this only ensured further stagnation. At the geopolitical level, however, the end result of this military brinksmanship was a rapprochement between China and the United States, spearheaded by the Nixon administration but actively sought by many within the upper rungs of the Chinese state, foremost among them Zhou Enlai.

Over the course of the 1960s, it had become increasingly clear that both autarky and military isolation were fundamentally unsustainable. Economic isolation led to increasing demand for capital goods that could not be produced domestically, and this demand encouraged the opening of diplomatic ties in the hopes of obtaining these capital goods. At the same time, isolation had led to the risk of simultaneous warfare on all possible military fronts—a coastal war with the US, an overland war in Manchuria and Central Asia with the USSR, mountain warfare with India in the Himalayas (following the Sino-Indian war in 1962), and both direct and proxy conflicts with Soviet-aligned governments in the jungles of Indochina. These threats had already led to a major shift in the geography of investment within China itself, with the Third Front development drive focusing on large military-infrastructural projects in China’s least-accessible interior provinces.[57] The political symbolism of the Third Front was stark and militaristic: after the Japanese invasion, the Nationalists had made a similar retreat to the interior, making Chongqing the wartime capital and building much of the basic infrastructure now used in the Third Front industrialization drive.

Following the border conflict in 1969, mending ties with the USSR was unlikely. Instead, China’s only real way out of isolation was to slowly warm to the overtures made by the Nixon administration. This process was spearheaded by Zhou Enlai, an ally of Deng Xiaoping who had long been China’s premiere diplomat. But the opening cannot be attributed to a single faction within the CCP leadership. First, it was more a response to the building domestic crisis than a political whim, driven in particular by demands for capital goods in the petroleum and fertilizer industries, both considered absolutely essential for the success of the industrial programs of the 1970s. Second, there was clear, if tacit, support for this opening among rival factions within the CCP leadership. In fact, diplomatic contact was initiated in the midst of the Cultural Revolution (albeit after the peak of 1969), and if Mao or the Gang of Four had opposed it outright it simply could not have happened. At first, this opening came via informal channels, beginning with the exchange of table tennis players in 1971, endorsed by Mao, in what would later be termed “ping pong diplomacy.” These informal overtures were followed by a series of secret meetings between Zhou and Kissinger later that year.

The US embargo against China was lifted by the end of 1971, and the next year Nixon and Kissinger formally visited China, the first time a sitting US president had ever visited the country. During the visit, Nixon and Kissinger had a single, brief meeting with Mao, during which the main outlines of Chinese policy were established. The remainder of their trip was composed of a series of meetings with Zhou Enlai, interspersed with gift exchanges and scenic photo-ops, and concluded with the issuing of the Shanghai Communiqué, to this day the foundational document of Sino-American bilateral diplomacy. Alongside the lifting of the embargo a year prior, the Communiqué provided the rudiments for future policy in the region. Though ambiguous in its wording, the document proposed the normalization of relations between the two countries, stated that the US was not seeking “hegemony” in the region (and implied that the USSR would not be allowed to seek the same, leaving open the possibility of US support in future border conflicts), and, most importantly, stated US recognition of the mainland government, including formal endorsement of a variant of the “One China” policy, accompanied by the commitment to close a number of US military installations in Taiwan. With the end of the embargo and the possibility for a peaceful resolution to the Taiwan conflict left open, this ambiguous diplomatic statement had opened the door for the growth of a much more substantial economic relationship with the capitalist sphere.

At this point, it cannot be said that there was any real long-term plan to “open” China to large sums of foreign investment. The intention of the Nixon administration was largely geopolitical, attempting to drive a wedge between the two centers of gravity within the socialist bloc. Alongside the end of the Vietnam War, the establishment of this “Triangular Diplomacy” was among the major achievements of Nixon’s long-term Cold War strategy. The strategic aim of the rapprochement was to gain flexibility and leverage in future interaction with the USSR while neutralizing a large potential military threat to the US (which had no interest in becoming bogged down in yet another war in the Pacific) and preventing the formation of any new Sino-Soviet bloc.[58] On the domestic side, even the pro-reform faction within the CCP saw this early diplomacy as part of an extremely limited program of liberalization aimed at solving a series of immediate domestic crises that had proved intractable within the autarkic conditions of the 1960s. But the reforms were intended to preserve and in fact revitalize the developmental regime itself. There was simply never any long-term strategy for market transition.[59] Instead, the transition was the emergent product of confluent crises, as a series of haphazard domestic reforms led to local marketization and rural industrialization at roughly the same time that the diplomatic opening converged with the long downturn in profitability in the capitalist sphere, driving a massive spike in trade (beginning in the 1980s) and foreign investment (beginning in the 1990s).

Nation, State and Family

Though it seems self-evident, it’s important to note here that the sort of international diplomacy engaged in by the Nixon administration presupposes coherent nations, and the capitalist world is necessarily a world of states that administer, cultivate and propagandize such national difference. In the end, the developmental regime’s success in forging the culturally diverse, politically fragmented East Asian mainland into a Chinese nation-state proved to be the necessary scaffolding required for relatively smooth entry into the capitalist world. This precondition is not a mere accident of geopolitics, however. The nation and the modern state, alongside older institutions of local power—most importantly the patriarchal family—have proven again and again to be essential to accumulation. China was no exception, and the completion of the nation-building process, one of the main goals of the developmental regime, would thereby become a key enabling factor in the transition. Meanwhile, the perpetuation of gender inequalities within the developmental regime—despite both propaganda to the contrary and real, substantial advances compared to life before the revolution—would ultimately provide the social space for the growth of a proletarian class, dominated in the first few decades by women.[60]

It is necessary here to take a step back and consider how, exactly, the abstract drive of accumulation is enforced in the flesh. Though the innermost logic of the material community of capital is oriented as if it were a smoothly-linked, fully global system, with no obstruction to the fundamental circuits of accumulation, the reality is that accumulation can happen only through the production of value in the real world, and this is an inherently messy process, constantly obstructed and constantly forced through. The law of value does not descend from heaven. It arrives on the back of gunships, in crashing waves of inflation, or like a spear poised behind the paper of treaties and loan agreements. Its baseline condition is that both resources and human labor capacity, initially exterior to the commodity system, be made and kept available to it as commodities. This means that areas outside the system must be absorbed into it, but it also entails that, despite repeated crises that cast labor out of the production process and leave rings of fallow rust-belt ruins, the commodity form of both land and labor must be maintained by any means necessary. When we discuss the subsumption of China into the material community of capital, then, we are discussing both a specific historical period, and the nature of the local mechanisms that assisted the transition. But, in many cases, these are also the means used by capitalism today to maintain the baseline conditions for the production of value.

A fundamentally economic imperative thereby takes on a myriad of extra-economic forms, often exapted from pre-existing power structures, and almost always carrying their own inertia into the new system. This results in mechanisms of oppression that are inherently in excess of the baseline economic needs of the system as a whole. In China specifically, this includes the general operation of the state (police, prisons, property law), but also specific tools such as the hukou system and the dang’an (档案)—ostensibly a mere administrative “record,” but in reality an individualized system of surveillance overseen by the Public Security Bureau. Both are exaptations that originated in the socialist era. Similarly, the role of national identity and its relationship to the concept of a distinct “Han” culture and ethnicity have been essential to both the general credibility of the state and the violent assertion of territorial dominance in places like Xinjiang and Tibet.[61] Meanwhile, the perpetuation of the family and widespread gender inequalities has been key in the creation and maintenance of a capitalist class system: marketization in the countryside took as its essential unit the productive capacity of individual households—the shift to the “household responsibility system” would not have been possible without the ability to mobilize labor through patriarchal family units. In addition, the early proletariat in China was dominated by women because of pre-existing inequalities in rural work-point allocation and urban employment, and the earliest private capital to flood into places like the Pearl River Delta was mobilized via clan networks.

Even though mechanisms such as these are dependent on and ultimately employed in service of these economic needs (within the circuit of value accumulation, they are not in any way truly “autonomous” or “semi-autonomous”), they cannot be reduced to mere economic causes. This is because their inertial quality gives them both an extra-economic character and a degree of internal consistency which generates the illusion that the state, nation, race, family, etc. are capable of surviving in their current form beyond the potential death of the economy. Such mechanisms are dimensions of what Marx called “original accumulation.” But these are also not leftovers from a certain “stage” of history, as many classical misinterpretations of “primitive” or original accumulation would have us believe,[62] nor are they a method of plundering a not-yet-subsumed “commons” that somehow persists after the transition, as is imagined in theories that recast original accumulation as “accumulation by dispossession.”[63] Original accumulation is not a mere phase in history—and history is, after all, a sort of living, writhing avalanche that tends to shake off any stages saddled onto it—nor is it dependent upon the persistence of a periphery (internal or external) to the capitalist system. Maybe most importantly, these processes are not simply defined by dispossession. The only essential feature of original accumulation is the act of establishing and maintaining the framework necessary for accumulation to continue—not the enclosure of some sort of interstitial commons, but now the perpetual maintenance of the material community of capital, which entails instead the foreclosure of the potential for communism.[64]

What this means for our purposes is that the very creation of the Chinese state—defined by the supposedly continuous and coherent culture of the Han ethnic group—and the persistence of the patriarchal family were necessary preconditions for a relatively smooth entry into the global capitalist system. But the contingency of this process is often disguised in hindsight. Since China did complete the capitalist transition as a nation, and since its government and familial infrastructure was exapted to serve the needs of continual accumulation, we can say that the creation of this infrastructure in the socialist era was, in fact, the birth of mechanisms for original accumulation, even though the developmental regime was not capitalist. This is equivalent to arguing that the pre-existing states and clans of Tokugawa Japan or Prussia under Frederick the Great would become essential to the formation of capitalist states, even while their own economies were by no means capitalist. This doesn’t mean that the very existence of the nation-state guaranteed the transition. Such states can and have collapsed in the midst of changing modes of production or in the face of opposing military powers (as the Chinese state itself experienced earlier in the century), and the transition to capitalism can be carried out in the midst of this balkanization, or on the basis of a new political center—in conditions of statelessness, one of the first acts of subsumption into capitalism was always cartographic, colonial powers drawing arbitrary borders and defining nations where none existed before. The most basic ideological presumption in a capitalist society is the willingness to project capitalism back into the past as if it were both perpetual and inevitable. Portraying the socialist developmental regime as if it were somehow secretly capitalist all along—or a mere stage of primitive accumulation clearing the way for capitalism—simply repeats this procedure, removing the contingency from history and reinforcing the myth of capitalism’s immortality.[65]

In reality, the creation of China as a nation state simply provided an opening into the international capitalist system, at best predisposing the array of probable outcomes in the general direction of transition. But if China had remained in a state of balkanization, it’s equally likely that invasion, colonization and debt-bondage would have had much the same result. Historical counterfactuals can only illuminate so much, however, and there is simply no function to inking out a potential path beyond capitalism that may or may not have existed last century. What we can conclude is that the infrastructure of government created during the developmental regime would, in the end, help to create and continually maintain a system for the commodification of land and labor-power. Similarly, the maintenance of the family unit would undergird marketization, proletarianization and the inward flow of capital. The exact paths by which such features were exapted in the process of transition will be explored below. But it is important to note here that, rather than a hindrance, the existence of an extensive state and pre-capitalist filial traditions were important mechanisms for the introduction of capitalism on the East Asian mainland.

The Limits of Spirit

In addition to geopolitical isolation, Chinese reformers were also responding to a slowly growing wave of domestic discontent. In part, this was an after-effect of the tumultuous peak of the Cultural Revolution, but it was also a novel type of late-socialist disillusionment generated by the ever-lengthening period of austerity alongside high investment. Early on, the new forms of quasi-religious communalism offered by the state, codified in campaigns such as the Socialist Education Movement, had some, albeit unpredictable, success in rationalizing continuing scarcity and rendering sacrifice for the sake of the socialist project into its own spiritual reward. But spirit always meets its limit in the flesh. Numerous ethnographies of the period document the process at the personal level: the model worker becomes caught up in the enthusiasm of the early Cultural Revolution, sacrifices the material incentives introduced following the Great Leap, and is rewarded with quasi-religious symbols of state patronage, which at first seem to have a true social weight to them—the picture of Mao is framed, the red book placed on a shelf, pins and red scarves affixed to outfits. But as the years stretch on these symbols grow hollow. Copies of the Little Red Book pile up next to stacks of Mao photos, too many to frame. The spiritual communalism of the era seems now to accrete nothing but these masses of useless tokens, and the symbolic framework of the state’s ideology begins to break down. Even the most model of workers cannot stave off the growing cynicism. At the mass scale, it manifests first in black markets, illicit businesses, hoarding, work slowdowns—all measures to satisfy the material at the expense of superior virtue. In the end, such cynicism will always begin to take on a more public character, and by the middle of the 1970s open unrest had again begun to grow. [66]

There had already been some retrenchment from the height of the heavily militarized Third Front investment push. Following the Lin Biao incident in 1971, the fear of a military coup encouraged the regime to scale back the army’s involvement in production, and reformers successfully secured cutbacks to bloated construction projects in the West in favor of more immediately productive investment being funneled back to coastal regions. Meanwhile, the early meetings with Nixon and Kissinger resulted in an agreement “to spend US$4.3 billion to import industrial equipment,” with a focus on “11 very-large-scale fertilizer plants from a U.S.-Dutch consortium.”[67] The immediate strategic goal was to preserve the developmental regime, not to implement wide-ranging market reforms, and certainly not to become fully incorporated into the global capitalist economy. But the reforms also had a tactical dimension, aimed at quelling the latent unrest building across the population.

In 1974 a new wave of industrial actions swept through the cities, more subdued than that seen in the late 1960s, but nonetheless widespread enough to signal that many of the same economic issues (stagnant wages, deteriorating welfare services) had persisted despite the rhetoric of the era.[68] Maybe more importantly, explicit critiques of the regime resurfaced in this period, but with much of the ultra-left suppressed in 1969, these critiques were now fused to a more openly liberal program demanding democratization and, increasingly, marketization. In Guangzhou in 1974, a series of big-character posters went up with the first major public statements by the Li Yizhe group, a loose coalition of young dissidents (led by Li Zhengtian, Chen Yiyang and Wang Xizhe) who had been briefly jailed at the height of the Cultural Revolution. Though falling short of the more radical propositions made by the ultra-left factions several years prior, the Li Yizhe group articulated a vaguely humanist-Marxist position, similar in character to that advanced by Eastern European dissidents, and notable for its ability (largely via Wang Xizhe) to justify this vision through an elaborate engagement with Marxist theory. The most impactful of their essays, titled “On Socialist Democracy and the Legal System,” was (indirectly but very clearly) critical of the regime, including the “new nobility” of the bureaucratic class, the Gang of Four and the cult of personality. Alongside an end to the mass arrest and imprisonment of dissidents, it advocated increased democratization, and some of its key authors would go on to become leaders in the Democracy Wall Movement of the late 1970s. The Li Yizhe document was tacitly allowed to spread by Zhao Ziyang (who would later become one of China’s key leaders in the reform era), at the time serving as Guangdong’s Party Secretary. Popular discontent was thereby, at least in part, cultivated and directed by some reformists within the party, who hoped that the political message contained in such critiques could be usefully mobilized against opposing factions.[69]