Lu Yuyu and Li Tingyu met me for dinner at a hole-in-the wall restaurant on a quiet street. Lu wore a ball cap, something he was rarely seen without, and a faint smile. He was hunched over the table, no doubt in the same manner that he bent over his laptop each night during hours of scouring social media for fresh news of protest before it had been scrubbed by the censors. Li beamed with a wide, playful grin, wearing sunglasses though we were indoors. She was not used to so much light, as the couple kept shades drawn at all times to keep prying eyes from spying on their sensitive work. As we sat down, they casually glanced around the room checking for plain-clothed cops. The couple had spent the past three years documenting the protests, strikes and riots that take place across China every day, and they’d been run out of several towns by state security forces over the years. This was why they’d moved to this rustic tourist town in Yunnan, thinking the police might be more lax here. But, not long after, they would be snatched from the streets of that very town and imprisoned for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” (寻衅滋事)—the default charge used to keep dissidents in custody until the police are able to build a more specific case—and their short-lived but important project would come to an end.

Li was born into a well-off urban family, but had inherited no wealth or social favors after she dropped out of school and severed nearly all communication with her relatives. Lu, more than ten years her senior, started out as a migrant worker from a poor village in the mountains of the southwestern province of Guizhou. Together they committed to a covert project that changed names over the years to avoid the attention of censors, but which became most widely known as “Wickedonna.” Starting officially in 2013, the couple conducted daily searches on Chinese social media platforms for news of “mass incidents” (群体事件)—the state’s catch-all term for any unwanted gathering—and published them on foreign internet platforms, beyond the reach of state censorship. Their project recorded the first-hand experiences of those directly engaged in struggle, saving their pictures, video and words, and then categorizing the events by scale, participants and demands.

The pair was dedicated to capturing the widest possible spectrum of social unrest available, rather than focusing on any particular segment of society. The blog itself was little known, but their nearly real-time records became the primary source for sinophone dissident websites (ranging from mainland Maoist factions to overseas anti-CCP news sites), as well as mainstream English news media, foreign academic projects, and international NGOs such as China Labour Bulletin and its “strike map.” Lu and Li have been lauded as “human rights defenders” and award-winning “citizen journalists,” titles all bestowed only after their arrest. But their own political intentions, and the political implications of their work, have never been seriously considered. They not only aspired to expose the wide spectrum of struggles occurring across society, but also wished their readers would learn practical lessons from the experiences they documented.

The two were much more than activists fascinated with street protests. They had developed their own political ideas through interactions with various political circles, mostly online, over the years spent huddled indoors. Beyond the vast data they gathered, the pair studied the networks that enabled the protests and ideas that drove them, and they had become involved in discussions taking place within networks of radicals, dissidents and activists of all types. They followed the work of labor NGOs in the factory zones, the political debates swirling in online forums and microblogs where various Maoists, liberal and left-wing academics, and the odd Trotskyist analyzed China’s unrest and jockeyed over the direction of social movements. The two considered themselves leftists of a sort, thought Marx was worth studying, and expressed an interest in anarchism. But their approach was markedly different to that of the normal online leftist: While the ideas floating through political circles were important, Lu and Li were primarily concerned with the mechanics of the phenomena they recorded every day, including modes of organization, changing trends of struggle, methods of state repression, and techniques of resistance. Above all, Lu said, “I hope that they study (学习)[1] these events, and understand their successes, failures and limitations.”

They survived on donations from supporters, some of whom gave but a few yuan when they could, while others donated several thousand each year. In a post from January 2014, the couple said they’d received some 20,000 yuan (about 3,000 USD) over a five-month period. The small flow of funds was enough to keep the lights on and sustain the eight-hour searching sessions they performed each evening. Most of these social media posts were made in the evening, they explained, so they often worked deep into the night to catch posts before the censors could begin scrubbing the internet.

The two were familiar with the revolutionary programs of multiple left-wing groups, both inside and outside China, though they didn’t ascribe to any clear position themselves. The breadth of their work, engaging with all sectors of society from urban homeowners to ruralites clashing with police over land confiscation, seemed to confound any orientation that prioritized a particular social group. They supported Chinese Trotskyist blogger Autumn Fire’s (秋火) independent analysis of strikes and worker organization, but were critical of Trotskyism. They studied the statistics of liberal sociologist Yu Jianrong, a famous academic studying China’s mass incidents, but were wary of how closely he collaborated with the government. The changing trends of struggles demanded constant attention and reevaluation that many of these theorists seemed uninterested in. In 2016, the pair were amazed by the growing number of homeowner protests, which, to their surprise, outnumbered labor struggles. The point was to show the real trends as they existed at any given moment, rather than fit them into a theoretical box filled with hopes and dreams about where things ought to go. When our conversation shifted to protests by religious groups, for example, my quip about the futility of religion was not taken lightly: “Well whatever you think, you must remember, they’re organized, so it’s important to understand,” remarked Lu.

Though all forms of struggle and organization were significant, Lu’s preference was for militant action, particularly against the police arm of the state. “If only people had guns in China, the police would never dare to mess with us,” Lu surmised. He admired the struggles of “ruralites” (农民), as the blog categorized them—residents of villages far from urban centers—and their courage to stand up to police and corrupt government officials with improvised weapons. The Wukan incident of 2011[2] made international headlines when the whole village attacked their local government building and withstood weeks of siege by armed police forces, but Lu knew that there were countless similar struggles developing nearly every day across the country, where ruralites might flip and burn police cars and stand down state security forces with farming implements.

Lu’s background is not very clear, and even his own story conflicts with court records. He said he was born in 1979, though records from his sentencing say he was born in 1977. The documents show he was born in 1977 in rural Guizhou, which has, by most measures, retained its status as China’s poorest province throughout the intervening forty years. As a child he walked an hour or more to school on mountain paths, though he never liked school, attending when he had to and skipping class when he could. He and his friends would often steal food from home, running off into the woods to form “brotherhood clubs” (兄弟会), living in the forest for days before their food ran out and forced them home. When they returned they were always beaten, but when the punishment faded they would elope again. Lu loved the idea of belonging to a wandering band of friends aligned against the world. He liked the Canadian television show Vikings for its depiction of close-knit clans that survive together, wander where they may, and take what they want. Court documents say he was imprisoned for “hooliganism” (流氓罪) in 1996, serving all of his seven-year sentence before being released in 2002.[3] Lu did not mention this stint in prison or the specific crime he was accused of, though he did say some of his friends in Guizhou had been killed by firing squad in the 1990s for stealing, when that form of punishment was still common. He said they stole to survive, rather than beg, because “they still had their pride.”

He left Guizhou to work in the coastal factories, briefly attended and dropped out of college, and then began spending his time after work on China’s budding internet platforms. It was through the latter that he became fascinated with reports about dissident activities and the world censored by the regime. In 2010 he was arrested in Shanghai for taking to the street by himself with a sign demanding publication of the wealth of top party officials. This was the first of his several years of participation in the short-lived “Southern Street Movement,” named after the large number of events in Guangzhou and Shenzhen around 2011, attempting to bring internet activism into the real world by hosting public discussions about political issues with ordinary people.[4] The failure of the movement forced Lu to reconsider his strategy. He scoured the internet for other signs of protest, and discovered that, with a few tricks to bypass filters and censorship, he was quite good at finding news of disparate collective actions across the country. He soon began dedicating all his spare time to documenting and transmitting as much of this information as he could.

Li Tingyu was born in Foshan in 1991, where she gradually became aware of the poverty, resistance and repression around her relatively privileged upbringing. She attended the prestigious Sun Yat-Sen University in Guangzhou, majoring in English and, outside of class, devouring all kinds of foreign literature, music, film and philosophy. Before long she grew disillusioned. She worked for the school’s foreign exchange program for a while, helping students get into academic programs overseas, but she discovered that her English teachers were being paid by rich students to write their entrance essays and fill out applications. Meanwhile, she had become fascinated with things hidden by the Great Firewall, such as struggles in Tibet, and with ways of circumventing censorship. All of this eventually attracted the attention of school authorities. She realized that students were working as informants in every classroom, and even her teachers ultimately turned against her. The administration gave Li a choice: if she put aside her troublemaking and graduated like the rest, she would find a good job and live out a good life. Otherwise, the university would make sure she would never have those things. Faced with this threat, she decided to drop out in the final year of her undergraduate program. Soon after her arrest years later, Li, speaking to her lawyer during a visit to her prison cell, recalled a discussion she had had with a friend attending Peking University, who had bragged about unrestricted internet access at the university and his plans to emigrate after graduation. In disgust, Li remarked, “Do you think there is dignity in living a good life in this country?”[5]

Lu and Li first met online. Lu gained notoriety in the online dissident subculture when he decided to quit his job and dedicate all his time to seeking out and reposting protest news, but his efforts only lasted a few months before he out of money and told his followers that he’d have to quit. It was Li who reached out, convincing him that perhaps, with a little effort and organization, his efforts could be turned into a long-term project supported by his network of fans. The two became friends, then partners, and before long embarked on the three-year journey that became the Wickedonna blog.

The Avalanche of History

Lu and Li came from different segments of an increasingly fragmented class: Lu was 39 years old at the time of his arrest, precisely the average age of China’s 280 million migrant workers. He represents the mass of rural migrants bouncing from construction sites to factory jobs for the last two decades.[6] Li, by contrast, represents the more highly educated urban millennial, inheriting only a small fraction of the massive wealth generated in China over her lifetime but placed in a social position directly proximate to it. In this position, skill and education is confronted with an absent future, as over-trained youths look ahead to the slow unfolding of a dead-end service economy, where they’ll be paid half of what they expected to perform mundane tasks far below their competence. These two dedicated themselves to examining the resistance around them and from this real movement trying to understand what might be rising on the horizon of struggle. Theory emerges from the unending avalanche of history. Any attempt to understand the greater organizational potentials foreboded by existing struggles must retain this relationship to reality. Lu and Li’s project originated in an often out-of-touch scene of online dissidents and leftists, where “theory” was little more than the pure play of ideas, as forum-dwellers sought to suture the dead flesh of century-old orthodoxies about workers’ movements and peasant armies onto the living muscle of struggles today. But their work very quickly ascended beyond this insubstantial sphere, documenting real events in a rigorous and systematic way and thereby becoming a threat to the state. It is this type of documentation that makes their project into an invaluable contribution to theory, since it gives us a clear sightline into the real movement of history. Among the most important of their findings is the fact that only a small portion of collective actions in China take the form of strikes. There doesn’t appear to be an industrial workers’ movement emerging in China—at least not in the form advertised by foreign leftists or China’s own online theorists, both of whose ideas are often modeled on a convoluted picture of the historical workers’ movement itself.

Instead, something else might sit on the horizon. But in order to trace out its distant silhouette, we must have a clear view of current trends. The data so meticulously compiled by Lu and Li, dangerous enough to cast them into prison, is equally threatening to conventional theories of the Chinese “labor movement.” From this data, it is clear that strikes by workers at industrial facilities, aimed at fighting for better wages and working conditions, do not seem to be gaining the momentum required to become the core of a broader mass movement. Using Lu and Li’s data we can instead identify the general trends of unrest in contemporary China: non-workplace struggles far outnumber those in workplaces, strikes themselves are only a small portion of all labor actions, and other forms are far more common, including riots, blockades and street demonstrations. These trends are produced by several convergent economic trends, including deindustrialization and a ballooning service economy, the stratification of the proletariat according to income and interests, and a general inability on the part of enterprises to afford net wage increases.

This does not mean that striking workers, industrial or otherwise, are unimportant in these overall dynamics. In fact, the continuing economic downturn will likely be accompanied by modest increases in industrial actions, as automation and factory relocation continue apace and strikes among service workers become more common. But in China today, as in many other countries, there is no existing or imminently emerging trend of militant industrial working-class identity that could become hegemonic among broader social movements. Instead, we see continuing decomposition of the proletariat into a broad array of waged, unpaid, self-employed or unemployed fractions, and a deeper stratification between high and low income strata. In such conditions, little common ground is in sight and no single class fraction appears to be capable of unifying the others. This is important because it signals the deeper resemblance between conditions in China and those in evidence elsewhere. Theorists in these other places to tend to project onto China a mirage of the very mass movements missing in their own high-income countries. This allows them to disavow any attempt to push their own local movements beyond current limits, immobilizing left-wing forces in local political contexts from formulating any alternative to identitarianism, electoralism or right-wing populism, since they presume that the real fight is elsewhere. The ultimate political result is deeply conservative. At its most mundane, it results in microscopic activist scenes constantly organizing “solidarity” campaigns to raise awareness and provide support to struggles elsewhere, succeeding in neither goal. At its most tragically ironic, it produces a situation in which Hong Kong activists and left-wing theorists pour all their energy and resources into relatively toothless worker centers across the border, completely ceding the increasingly riotous terrain of Hong Kong politics to the far right while doing little to stimulate the growth of a true mass movement on the mainland.

Rather than coalescing under an affirmative “worker” identity, subjectivities of a different kind are forming in relation to the present structure of the Chinese economy. A communist prospect, if possible at all, must be collectively constructed, rather than imported from insular activist or academic circles. Moreover, it must stretch across deeply fractured segments of the proletariat despite their conflicting interests, and today seems unable to rely on a single, hegemonic subject said to represent the interests of the class as a whole, as the mass industrial worker did (briefly and with questionable results) for the labor movement of old. If this communist horizon arrives, it will almost certainly take on a form initially alien to our expectations, adapting pre-existing identities in unpredictable and even unpalatable ways. Phenomena like the rapid popularization of the term “low-end population” (低端人口) in the aftermath of the 2017 Daxing fire in the southern outskirts of Beijing offer some hint of a possible future. Though not inherently revolutionary in nature, the term gathered together diverse fractions of otherwise isolated segments of the proletariat, from delivery drivers to factory workers, small shopkeepers and white-collar workers all living in the slums of the nation’s capital, and all facing mass eviction—notably a housing dilemma rather than one centered on the workplace. For a brief moment these groups were forced to reconsider their relationship to one another and their collective future in China’s increasingly fragmented society.

But an attempt to understand the real movement of history today also means coming to terms with distasteful facts. Today, as Lu and Li’s data reveals, struggles over housing are the single most common form of protest in China, and these are driven by largely reactionary interests in defense of property rights. This alone shows the political risks involved in China’s changing class structure, where the culture of the affluent few takes hold of a society whose immiserated majority lack a common emancipatory vision.

Strikes, Riots and the Rest

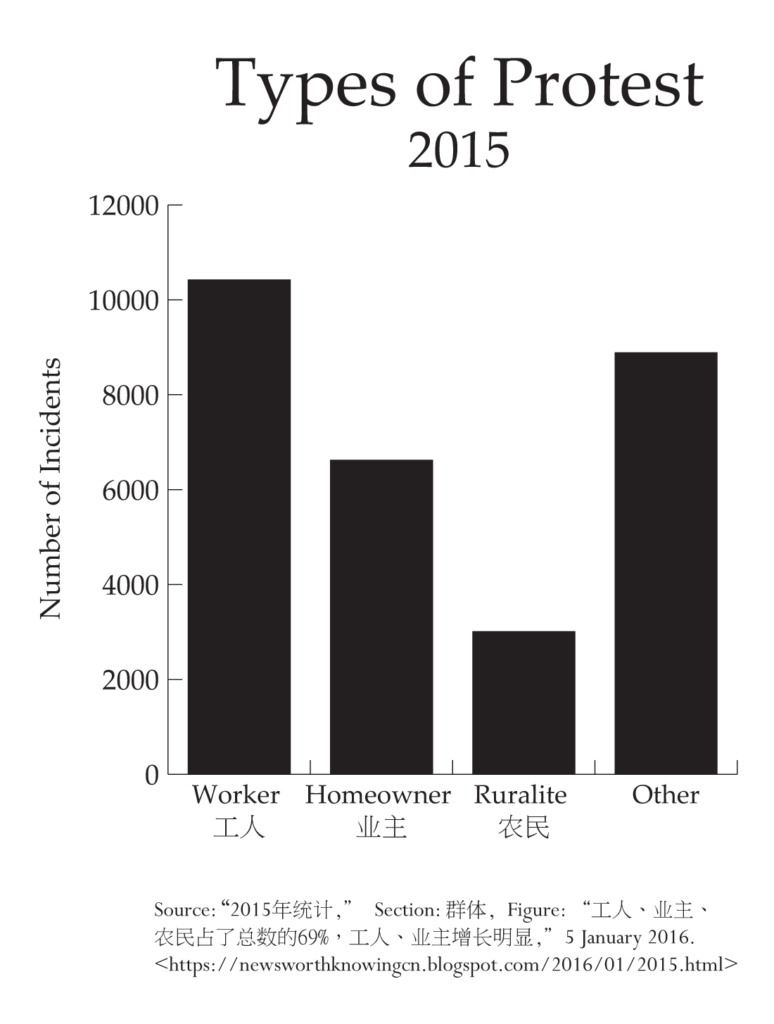

Lu and Li’s records searched for any and all social unrest within China, and the pair gradually constructed their own methods for categorizing events and actors. They collected more than 70,000 incidents between 2013 the time of their capture in 2016. In 2015, their last full year of data, they collected some 28,000 mass incidents, an average of 78 per day, with three main groups of actors: “workers” (工人) “property owners” (业主) and “rural residents” (农民). These three groups together account for some seventy percent of the protests, while the remaining thirty percent were a mix of around two dozen kinds of social unrest, ranging from retired army veterans demanding unpaid benefits to conflicts stemming from families who lost loved ones to a corrupt and overburdened health care system.

The data confirms assertions we have made elsewhere, using different sources. Lu and Li’s data, however, is very different from one of the key statistical sources of data on social unrest in China that we drew on previously, the Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone (GDELT).[7] GDELT uses media citations from major news services to catalogue daily records of incidents, stretching back over decades for both China and the world as a whole. The records provide great consistency over a decades-long timescale, though the data points are limited to describing a single node—a strike, a riot, or a demonstration—and lack the extreme detail of each incident logged on Lu and Li’s blog. The GDELT data allowed for a comparison of two main types of incidents (what GDELT categorized as “strikes” and “violent protests”), showing that riotous protests greatly outnumbered strikes over the thirty-year sample period. While strikes did become more frequent in the 2000s and 2010s, riots still increased faster. GDELT, however, is an imperfect tool, used in the absence of superior alternatives. Among its imperfections is its inability to provide a reliable number of specific incidents. Instead, it proved more feasible to measure the relative number of incidents as a portion of total events, capturing their social impact but making it difficult to understand the true volume of strikes or riots without supplementary measures. Working with GDELT data, then, is largely limited to descriptive statistics about this mass of media reports and cannot be usefully mobilized for inferential purposes.

More detail is offered by Lu and Li’s data, which confirms the more general picture we obtained from GDELT. Workplace struggles compose around forty percent of the total incidents, and are less common than non-workplace struggles, which make up the other roughly sixty percent. Strikes, in turn, account for only around ten percent of all workplace struggles, and are but one kind of action in a much wider array of resistance. Lu and Li don’t use a category that can be easily equated with “riots,” but their data has included a consistent category for “strikes” throughout the years of its operation, allowing for some longitudinal comparison. Though the categorization of incidents changed slightly over time, each period reflects a similar picture, in which strikes play a minor role in the broader picture of unrest.

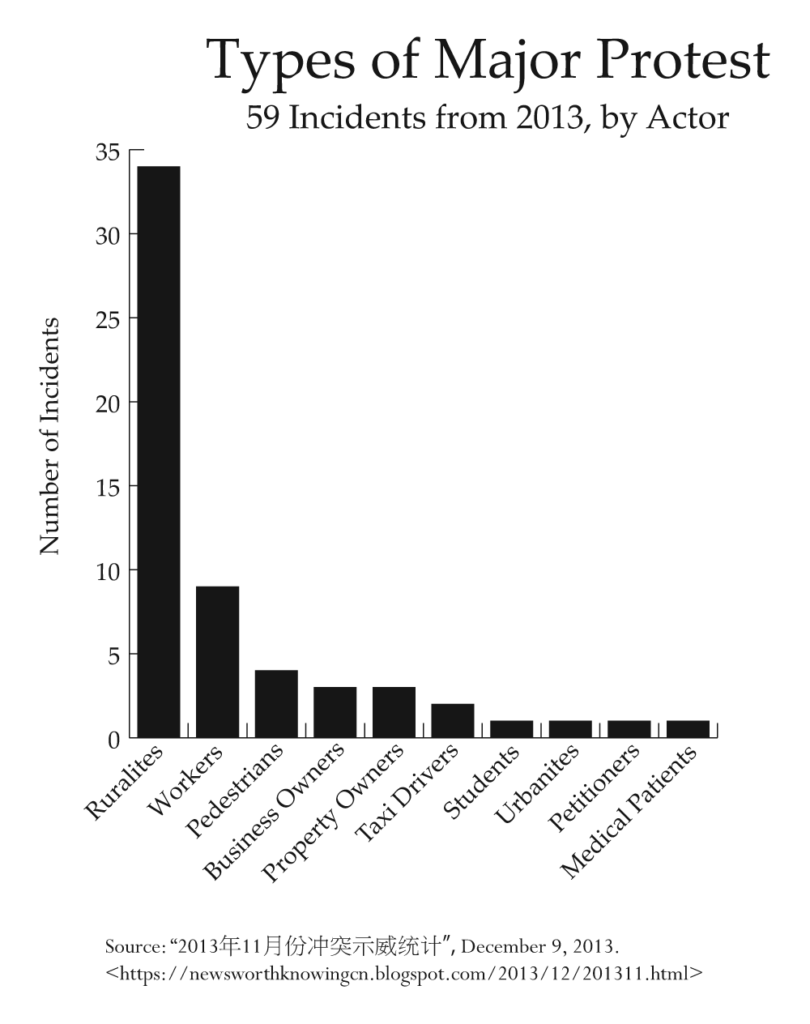

When the blog first began in 2013, for example, Lu and Li organized primarily by type of action, rather than by actor, and did not perform much statistical analysis on their total data. They did occasionally describe trends in the biggest, most significant events that occurred over a particular time period. For example, in November of 2013, the blog highlighted 59 major conflicts out of the hundreds that occurred that month.[8] The incidents were divided into two major categories, “clashes” (冲突) and “demonstrations” (示威). The thirty clashes were similar to what is normally referred to as a riot in English, in that they were violent non-workplace protests. For example:

1 November: Government sent police to forcefully expropriate land in Liucheng Village, Nanjing. Many villagers beaten.

7 November: Several hundred people in Guiyang, Guizhou surround chengguan[9] who had assaulted a street vendor. Many police on the scene.

9 November: In Longgang District, Shenzhen, homeowners from the Kangqiao Residential Complex demonstrated against a factory emitting poisonous gas into the air. Protesters beaten by police, several people injured.

26 November: Government sent three hundred chengguan and police to the Dali Pedestrian Street in Foshan, Guangdong to expel street vendors, resulting in a clash. Many vendors were injured, including pregnant women, and nearly a thousand people gathered at the scene. Afterwards, the vendors who had been beaten gathered at the government [building] to demand an explanation, but were repressed, with over ten arrested.

The other 29 were called “demonstrations,” among which ten were actually strikes—just seventeen percent of total major incidents. The two most frequent causes of all 59 disputes were “land confiscation and demolitions” (at 30%), and “environmental destruction” (at 25%). Labor conflicts only slightly outnumbered incidents against chengguan violence. One third of the incidents occurred in Guangdong province.

Later, Lu and Li began categorizing incidents primarily by actor, rather than by the type of action. Nonetheless, it’s clear that non-workplace resistance outnumbers that in the workplace for every year measured. In 2015, the last full year of data, those whom Lu and Li called “workers” accounted for 36 percent of the total incidents.[10] The final number of workplace-related incidents is slightly higher (at 39%), when adding groups like taxi drivers and teachers who were categorized separately. Only around ten to fifteen percent of these workplace incidents were strikes, however, with other forms of action including road blockages, demonstrations, marches and clashes with police tending to dominate. This more coherent picture from Lu and Li’s work in its final full year helps put workplace-related incidents in their rightful context amid the wider array of social unrest.

Trends in the Data

In 2015, the last full year of data, Lu and Li recorded over 28,000 mass incidents, including 10,000 by workers, 6,600 by homeowners and 3,000 by rural residents. In some respects, the figures are similar to other reports on the social composition of mass incidents in China, and while their records showed tens of thousands, there are surely tens of thousands more incidents that actually occur but never leave a trace on social media, or are scrubbed before anyone gets a chance to record them. The composition observed in Lu and Li’s data is, however, confirmed in other sources. Sociologist Yu Jianrong, who has released some of the few relatively comprehensive statistics about mass incidents in China, said as late in 2015 that the top three categories of actors were “workers,” “rural residents” and “homeowners,” though he did not provide a breakdown of the proportions, or the number of incidents.[11] A decade earlier, however, Yu said there were around 87,000 mass incidents (in 2005), and he did provide a more detailed breakdown of social groups: rural residents accounted for 35 percent, workers for 30 percent, “urbanites” for 15 percent, and 20 percent for other kinds of “social unrest” and crime, by his reckoning.[12] In Lu and Li’s data, workers are the largest category annually because of a massive surge in construction worker protests in the two or three months leading up to the Lunar New Year. We will, however, describe the categories according to their day-to-day prevalence instead. In this sense, the order is modified slightly: homeowner protests come first, followed by workplace-related struggles, and, finally, those of rural residents.

The data initially baffled the couple, since it exhibited trends that neither Lu nor Li expected. In their own notes about the major changes in 2015’s struggles compared to the previous year, they noted that real estate-related struggles, both by homeowners on the one hand and the construction workers who built the homes on the other, had grown the most.[13] Day to day protest logs showed homeowner protests outnumbered worker protests by some 20 to 30 percent on an average day. While Lu and Li could only manage to provide monthly or annual analysis of their own data, one academic, Christian Goebel, has extracted statistics from the blog down to the day, categorizing them by actor and action, and subjecting the blog, with its 74,452 events collected over three years, to rigorous quantitative analysis.[14] Goebel notes that the “overwhelming majority of protests in China is very small, mustering less than 50 participants. Still, more than 2,000 events were believed by participants to have been attended by 1000 persons or more,” averaging around two such protests per day over the three-year period.[15] His analysis shows that homeowner protests rose dramatically as a portion of the total, while land, labor and other common forms of protest fell.

Homeowner protests have existed in China since the opening of the housing market in the 1990s, but have intensified rapidly over the past decade or so. One major driver has clearly been the housing boom, and it is notable that most housing protests are located in second- and third-tier cities in places like Henan, Sichuan and Shaanxi, away from the coastal economic hubs. The events tracked by Lu and Li appear to be the fallout of a building spree that occurred in these cities as businesses fled rising wages for the cheaper labor of the interior beginning in the early 2010s. What began as a trickle of angry homeowner protests in 2013 (when Lu and Li began collecting data) became what is probably the most common form of protest in China today. It’s important, then, to understand the character of these struggles: Typically, homeowners protest against real estate projects that fail to deliver on their promises. Many homes in new developments are bought far in advance of their completion. These complexes come with promises that schools, parks and other facilities will soon be built to serve them, and agents ensure buyers of the future property values expected when houses are handed over. Quite often, however, projects run into problems. Planned schools fall through, facilities are less lavish than promised, and the overall quality of housing is far below buyers’ expectations, leading to organizing and protest among the new owners. Most often, buyers complain of shoddy construction or late handovers of their properties when developers run into complications, such as the bankruptcy of a subcontractor or changes in the local government’s zoning plans. In the end, buyers are left with a breach of contract and millions of yuan, often their life savings, on the line.

The most common grievance of homeowners, according to the categories constructed by Lu and Li, is that they were “cheated” by real estate companies in the process of building, or that the homes were delivered to them late or in incomplete condition. Ten percent of homeowner incidents involve residents who organize against property management firms for raising rents or fees, or for mismanaging the complex. Homeowner actions are distinct in the level of organization and amount of resources made possible by the participants’ greater overall income relative to rural residents or migrant workers. They often wear coordinated, custom-made t-shirts, for example. Homeowners are also more open about their organizing: Photos archived by Lu and Li show public events featuring full Powerpoint presentations. This may demonstrate the relative confidence among owners (as opposed to factory workers, for instance) that their efforts are legal and will find widespread support in society and even among state officials. Homeowners often target government buildings, an action framed as “petitioning” (上访),[16] although sometimes this evolves into the obstruction of gates or roads (堵门、堵路)—forms associated elsewhere with such struggles in the spheres of circulation and social reproduction. Overall, homeowner protests have been depicted as more “rational” and less “violent” than rural land disputes or worker strikes in industrial zones, but statistically speaking, homeowners are no less likely to experience police intervention, assault and arrests, according to Lu and Li’s data.

On an average day, worker protests are the second largest category of protest, though as already mentioned they compose the largest category annually due to their seasonality. The pre-New Year wave of protests, rising to their climax in December through January or February (depending on the date of the lunar holiday), is dominated by construction workers demanding unpaid wages owed for projects they had been working on for months, or sometimes even years. In China’s construction industry, workers are typically paid a small daily stipend, with the vast majority of payment postponed until the project is completed, or just before the workers return to their distant homes for New Year. The pressure of the approaching holiday pushes workers to demand payment in a variety of extreme ways that don’t, and usually cannot, include a work stoppage of any kind, since most of the projects have either been completed or gone bankrupt. Collective actions include road blockages, demonstrations at government buildings, and threats of suicide often made by workers standing atop the structures they’ve built, displaying banners and threatening to jump if they’re not given what they’re owed. Beyond the New Year surge, everyday actions by construction workers occur in the same fashion. Altogether this sector accounts for forty percent of China’s labor actions each year.

Even most worker actions outside the construction sector appear, at least on the surface, as a kind of protest with no sign of a work stoppage: holding a demonstration at a local government office, or raising a banner outside the workplace and posting pictures of it on social media. Of course, each collective action involves many unseen layers of activity: days, months or even years of communications among workers, confrontation or mediation with bosses or the authorities, or lawsuits, lawyers and bureaucratic procedures with government bodies. Only a fraction of these struggles escalate into the sort of public demonstrations that break into social media and records such as Lu and Li’s blog. Among these, about fifteen percent have police involvement, and five to ten percent involve arrests, according to 2014-2016 statistics from the China Labour Bulletin—which used Lu and Li’s data as a key source.

According to the same statistics, strikes account for only ten to fifteen percent of all labor actions across the board, and growth in the service sector seems to have intensified this trend. Work stoppages are particularly rare in the service industries, though the portion of workers employed there is the largest and growing rapidly. While this marks a real shift away from the type of mass strikes that are possible in large factory complexes, we should also note that work stoppages are almost surely higher than what is shown by publicly available records. Careful on-the-ground research shows that small, hidden stoppages of production occur quite often without ever entering a government stat book or appearing on social media.[17] This is only to say that we should neither romanticize nor completely discount the potential of workers’ direct experience of the strike as a form of resistance. Demonstrations nonetheless comprise the most common type of labor struggles.

Actions by rural residents are the third largest category, though they are gradually declining in number. Goebel’s analysis, for example, shows that land grabs and evictions, the primary causes of rural struggles, were declining as a share of all incidents throughout the period covered by Lu and Li’s data. Rural struggles as a whole accounted for a third of all incidents in 2008, according to Yu Jianrong’s findings, whereas now they comprise only ten percent, though they are still among the largest and most explosive conflicts in China.[18] Rural struggles center on land grabs and forced demolitions, in which local officials force residents out of their homes with little to no compensation for real estate projects or other more lucrative ventures. By association, these protests often focus on the corruption of local officials, as well as environmental issues. Environmental conflicts, another major protest category, often arise in such areas because environmentally destructive industrial activities are integral to the local government’s development policies. While smaller in number than incidents centered on labor disputes or urban homeowners, unrest among rural residents is often the most violent, involving both brutal attacks by police and highly organized, sometimes armed, resistance by rural residents.

Where is the Labor Movement?

In the same way that China acts as a disavowed dumping ground for many of the dirty realities of industrial society, it has also proved to be a sort of junkyard for obsolete political programs. The most familiar, of course, is the mirage of a workers’ movement amassing somewhere just beyond the horizon, its silhouette a faithful reproduction of the (equally mythical) summit of industrial organizing in the West. Such an eternally delayed Chinese labor movement has been predicted for decades by figures across the political spectrum, both inside and outside of China. Lying along the spectrum from liberal to Leninist, these theorists all draw on a more or less common understanding of their foundational myth, derived from an extremely brief period in the much broader and more diverse historical workers’ movements of Europe and North America. This myth reduces that experience to a few key elements that wielded hegemony only temporarily, if at all: wage workers, led chiefly by the core industrial workers in large Fordist factories, fighting strategically for better wages and working conditions (though perhaps also harboring political goals of revolution or reform), using the strike as their primary weapon of struggle, and the union as their essential form of organization. In reality, this view simultaneously bastardizes history and mutilates any understanding of present potentials.[19] It is marginally important, however, as an ideological foundation for what are essentially conservative positions arguing that politics be contained through displacement: if the real movement is occurring in China, politics elsewhere is reduced to mere activism or academic analysis, conducted from a distance. It is not purely coincidental that such analysis thrives on prophecy, since its basic structure is similar in nature to the displacement of political desire into religion. Despite the persistent absence of such a labor movement in China, then, onlookers have on different occasions hailed “turning points” that might bring about such a movement, from the mass layoffs of state-owned enterprise workers in the late 1990s to the wildcat strike waves of the early 2000s in the sweatshops of the Pearl River Delta. Among the most recent of these failed prophecies was the 2010 strike wave, sparked by the iconic strike at Honda’s four main automobile production bases in China.

The Honda strike illustrates the misplaced hopes of those who saw in it the potential re-emergence of the historical workers movement in China, led by fiery industrial workers aggressively demanding wage and benefit increases all wrapped together in demands for greater trade union representation and collective bargaining. The strikes of May 2010—the largest involving two thousand workers at the Honda parts plant in Nanhai, Guangdong[20]—were seen as a turning point for workers’ unrest in China. Young workers, reacting against years of inflation alongside stagnant wages, won significant pay increases, inspiring a wave of strikes at about sixty other auto plants and other types of factories across the country, followed by nationwide wage increases.[21] Representatives of the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) opposed the workers, attempting to break up their demonstrations and compel them to return to their posts. The strike became a sensation in both domestic and international media, with intellectuals, activists and reporters flocking to the Nanhai plant. Their influence was not just symbolic: One high-profile labor academic, Chang Kai, was instrumental in mediating a deal for the workers, but he also reshaped their demands, convincing them to add a process of collective bargaining to the list. The incident was soon resolved, and workers gained a 35 percent pay increase. Meanwhile, reformers within Guangdong’s provincial level of the ACFTU seized upon the strike as an opportunity to push for greater union involvement in labor disputes. To this end, they increased the number of pilot projects for plant-level union elections, establishing a version of tripartite labor relations (i.e. meetings between representatives of labor, capital and government to reach agreements on wages and conditions), curbing strike actions and labor disputes, stabilizing wages and working conditions, and attempting to create new relevance for the long-ossified ACFTU.

Some onlookers, like world labor historian Beverly Silver, felt that the striking Honda workers would resurrect the labor movement, which had been “prematurely” pronounced dead by the end of the 20th century.[22] In reality, the superficial appearance of a domestic debate on building a new workers’ movement actually disguised deeper machinations within the state’s apparatus for controlling dissent. The ACFTU’s reformist wing, propelled by the strike’s energy and bolstered by the international attention, drew on the language and even support of academics and NGOs to make their own case for a better, softer method of suppressing unrest. Silver and others presumed that the autoworkers’ strike wave was a sign of an organized, militant labor movement on the rise, citing the examples of the US in the 1930s and Western Europe in the ‘60s, and then force-fitting events in South Korea, South Africa and Brazil into this same model, as if history had produced no novelties since the middle of last century.[23] In this myth, rapid industrialization always lead to predictable sequences of militant worker resistance and unionization, leading the working class to push for more general reforms and revolutionary demands. On its own, this is simply a case of underwhelming scholarship. But in the larger picture, the rudiments of this work have been mobilized for conservative purposes.

In reality, the Honda strike was notable for two main reasons. First, it marked a major attempt to reorient the ways in which the state suppresses dissent in China, and thereby played an important role in continuing factional conflict within the capitalist class. In that way, it can be seen as the urban-industrial counterpart to Wukan village’s 2011 experiment in democracy, which was mobilized in a similar way.[24] Secondly, 2010 heralded the beginning of the end of a particular era in which coastal factory strikes had risen to prominence among the variety of collective actions taking place in China every day. It was, then, a peak of sorts, beyond which lay a descent into another vast hellscape marked by changing geographic and sectoral patterns of labor actions, shifts in the national composition of employment, and new trends in investment and state policy.

After Honda, many expected a generalization of the turn from “defensive” to “offensive” actions, in which workers would strike for wage increases beyond existing laws and norms rather than “merely reacting” when bosses pushed them too far and failed to meet legal standards.[25] In the years that followed, however, these “reactive” demands (for unpaid wages, social insurance, etc.) remained dominant in labor struggles. Wages did in fact rise for workers across China, but not necessarily in response to fear of worker rebellion: other, probably more determinate causes were inflation, policy changes raising minimum wages as part of an effort to restructure the basic geography of industry and, most importantly, competition over a slowly shrinking pool of able-bodied workers, driven by the final exhaustion of the rural labor surplus and a shrinking demographic dividend caused by the lower birth rates that accompany urbanization. While average wages have risen steadily since the Honda strikes, in many cases, especially in recent years as China’s growth rate has begun to slow, low-wage workers have made few gains or have even seen their real incomes decline as inflation has continued to climb. Guangdong province, the heart of the 2010 strike wave, instituted a three-year freeze on minimum wage increases between 2015 and 2018. Meanwhile, workers themselves rarely pushed for wage increases beyond their legal entitlements, instead usually fighting to achieve bare minimum standards like their legally required social insurance payments or wage arrears.

In the years following the Honda strike between 2011 and 2018, two thirds of all manufacturing demands were related to wage arrears, while only nine percent involved calls for wage increases. Records of workers’ demands during these changes help to signal this general trend, also hinting at the waves of relocation and closures that began just a few years after Honda. In 2011-2014, demands for wage increases in manufacturing occurred in around nineteen percent of the cases, while the most common demand was still wage arrears, at forty percent. Then, from 2015 to 2018, wage arrears demands jumped to 76 percent while calls for pay increases actually dropped to a mere 3.3 percent. Also during this period, strikes and protests in response to factory relocations and closures rose significantly, accounting for 15.7 percent of the incidents.[26] In 2015, even the famed workers of the 2010 Nanhai Honda strike were still struggling against rapid increases in the cost of living.[27] While in 2010 workers had won a 35 percent increase and greater participation in the plant-level union structure, they found themselves striking again in 2013, this time against the union, when offered an annual raise of only ten percent. A one-day strike brought the level to 14.4 percent, but in the following years, even this proved insufficient to meet the rising costs of housing, food and other goods. China’s leading industrial workers found themselves fighting just to keep up with inflation in an environment that is quickly becoming unable to provide even the most basic concessions a labor movement would ask of it.

All these changes—from the prevalence of defensive demands to the relocation of factories and the falling size and frequency of manufacturing-related strikes—correspond to the changing structure of the economy. In 2010, just when some expected striking factory workers to lead the way for China’s proletariat, employment in manufacturing was nearing its historical peak. Plateauing in 2013-2014, it has since begun a steady decline, measured as a share of total employment.[28] This decline was concurrent with mass factory closures and relocations beginning in 2013, which caused some of the largest and most contentious strikes in recent history.[29] Nearly all of them fit a pattern: these strikes did not involve demands for significant wage increases at enterprises with healthy profit margins. Instead, they consisted mainly of pitched battles for unpaid wages and benefits at factories facing closure, relocation or downsizing, sometimes requiring the company to liquidate assets simply in order to pay off what it owed. Labor NGOs intervened in many of these strikes, hoping to put traditional “labor movement” ideology into practice by directing workers toward collective bargaining and union reform. Workers at these factories, along with the NGO organizations involved, put together some extraordinary long-term campaigns involving strike actions, bargaining with employers, petitioning of the government and sometimes clashes with the police, only to find in most cases that their bosses had very little to offer them due to the shrinking profit margins that had given rise to the disputes in the first place.

The period was by no means empty of major strikes, some even winning fairly large victories: In 2014, around a thousand workers at garment manufacturer Artigas in Shenzhen began a series of strikes for unpaid overtime and social insurance contributions.[30] Between 2014 and 2015, workers at the Lide Footwear factory in Guangzhou took part in multiple strikes, demonstrations and negotiations with management.[31] With the aid of local labor NGOs, they won over 120 million yuan in severance pay and unpaid wages and benefits. The 2014 Yue Yuen Footwear strike in Dongguan, involving 40,000 workers (making it probably the largest industrial action in recent Chinese history), took place amid fears of the factory’s long-term plans to downsize and shift production to Southeast Asia.[32] Further strikes occurred at that and other Yue Yuen plants the following year when the company continued to consolidate production. But, altogether, the strikes in these years were hardly offensive, and rarely demanded wage increases, instead focusing on unpaid wages, severance pay, social insurance and other demands that accompany the downsizing and relocation of factories. Thus, though large, the strikes that did occur were essentially a fading echo. And in the years after Yue Yuen, the overall trend has been a general decrease in the size of labor actions.

Deindustrialization

These trends in worker protests track changes in the industrial composition of the country more generally, which has begun to shed labor in a manufacturing sector stricken by an ever-building overaccumulation crisis. Though official policies are now geared toward building a “consumer-led economy,” this vision is largely a mirage generated by the faulty presuppositions of mainstream economics. In reality, the subsequent shift of employment into services is more the result of diminishing returns to investment in manufacturing in the context of a tenuous macroeconomic stability secured by similarly diminishing returns to state-led stimulus. The result is an enormous amount of surplus capital with nowhere to go. On the surface, this appears to be driving a boom in consumption and catapulting the coastal cities into service and high-tech industries, mirroring the ladder of industrial upgrading already experienced in Japan and the other East Asian late developers. But these other developmental stories were predicated on the outward movement of capital as well, with Japanese, South Korean and Taiwanese firms passing through a series of trade wars to ultimately secure their status as intermediaries in the new productive chain stretching from mainland China to the consumer cores of the West, with Hong Kong and Singapore acting as new shipping and finance hubs. Throughout, this process was marked by severe domestic crises and capped by an unambiguous capitulation to US interests.[33] It is not yet evident, however, that a new nucleus of production has even been found. Strained by thinning profit margins, capital began to move to the Chinese interior in the wake of the 2008 crisis, but the gains of this relocation have been minimal compared to the earlier industrial boom in the coastal sunbelt. Meanwhile, production has been moving overseas, to South and Southeast Asia, as well as parts of Africa, but the returns of such outward investment are not yet clear, even while they’ve already triggered a new round of jostling within the global political-economic hierarchy.[34]

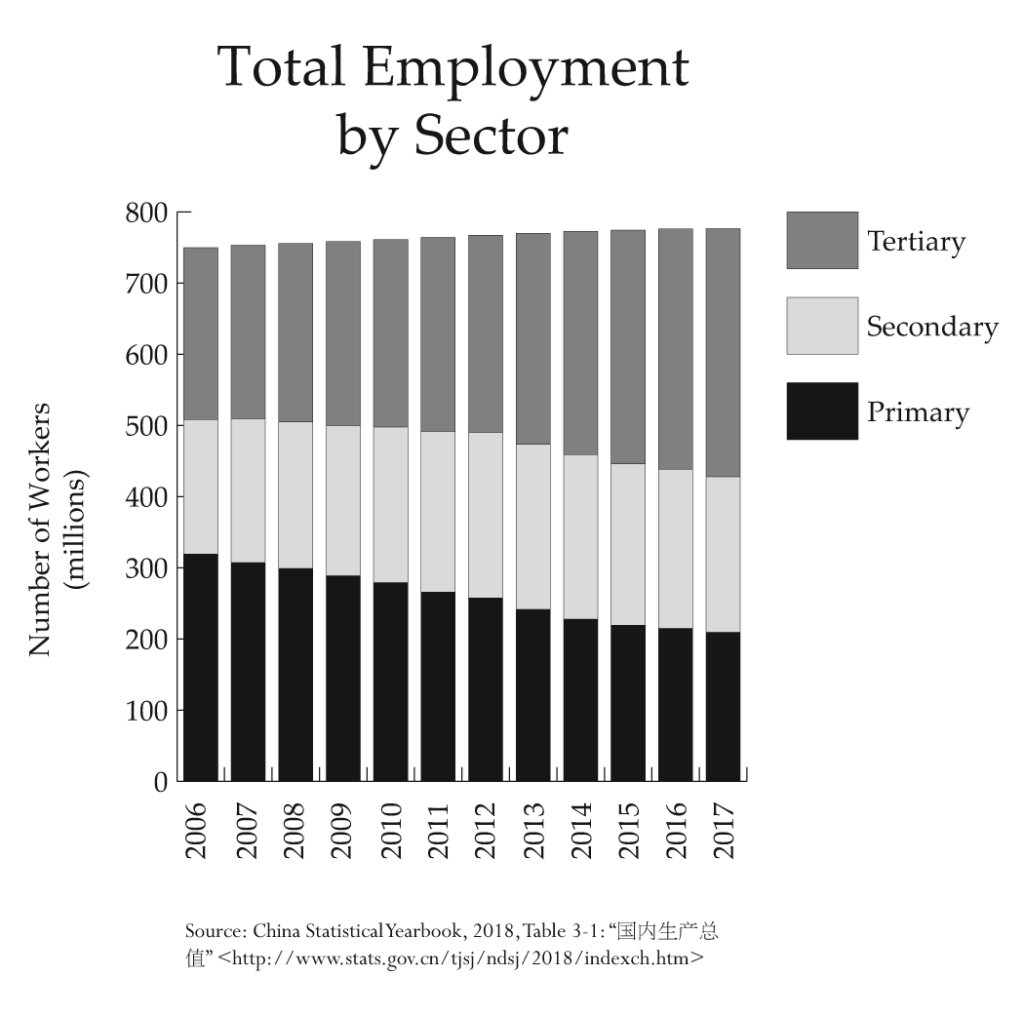

The basic Chinese macroeconomic picture can be seen from government statistics. The data lacks detail, and recent scandals around false reporting of provincial GDP data act as a continued reminder of the danger of relying exclusively on official figures, but they nonetheless capture in broad strokes the unmistakable movement of deindustrialization and the rapid expansion of the service sector.[35] Employment in the primary sector (limited to agriculture and forestry by Chinese reckoning) has been falling as a portion of total employment for decades, and declining in the absolute number employed since a peak in the early nineties.[36] The secondary sector (construction and “industry” in a narrow sense including manufacturing, mining and power), peaked in relative employment in 2012 when it accounted for thirty percent of the total before beginning a steady decline. This was matched by a similar, albeit slightly more moderate, trend in absolute employment. The tertiary sector (“services” and “circulation”) has, in turn, exploded and is fast approaching half of total employment. In terms of contribution to GDP, China’s secondary and tertiary sectors have switched places since the Honda strike. In 2010, secondary sector contribution hit a twelve-year high of 57.4 percent of the country’s GDP, while the tertiary sector stood at 39 percent. The latest statistics show that by 2017, secondary sector contribution fell steadily to 36.3 percent, while the tertiary sector climbed to 58.8 percent, by far the highest share in the country’s history.

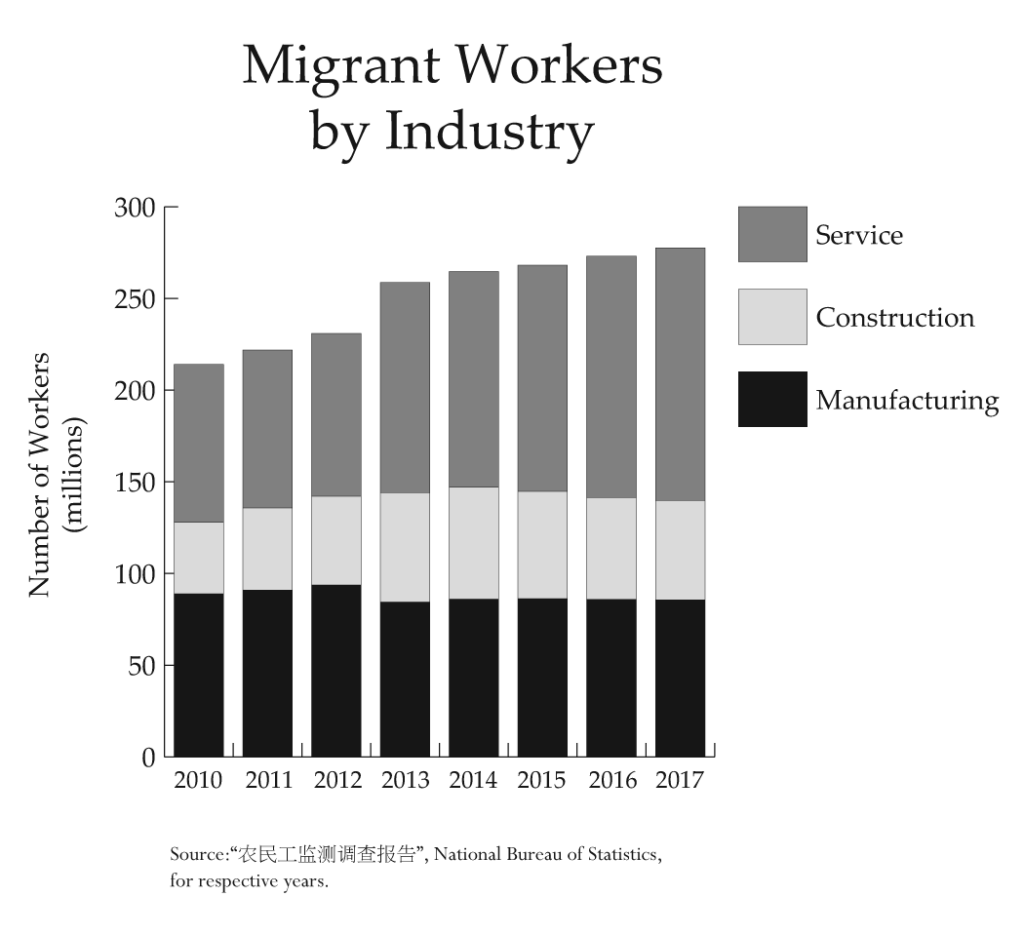

Other official statistics, like the government’s annual survey of “peasant-workers” (农民工)—those with a rural hukou working outside of their home county—show that today almost half of China’s nearly three hundred million migrant workers from the countryside now work in tertiary industries like retail, transportation, food services, etc., and the numbers are growing. The figure is almost on par with secondary industries, in particular construction and manufacturing—inflated by the fact that declines in manufacturing employment were countered with massive public works investment paired with the continuing housing bubble, all creating construction jobs ultimately dependent on either state investment or speculative real estate deals. Soon, no doubt, services will overtake manufacturing and construction as the primary employer of this segment of the population, especially as infrastructure and real estate investment reach a point of saturation.

Even in Guangdong province, the heartland of China’s export-oriented industries, manufacturing peaked as a share of employment in 2011, and has been falling ever since.[37] Still, output and profits in Guangdong appeared to be rising in data available from 2010 to 2015, even as the number of workers in manufacturing fell, a “natural” product of industrial upgrading, automation and increases in productivity.[38] While squat “sweatshops” pumping out textile piecework or plastic parts still chug along in pockets of the province, vast swaths of Guangdong are transforming rapidly away from what they looked like a decade ago. Wave after wave of closures have been welcomed by government bureaucrats, pushing out low-end, labor-intensive industries in favor of higher tech factories in an effort to upscale. Factory districts have been converted into logistics centers, and sometimes even flashy new “tech and innovation hubs,” in an effort to revive industrial production. The apex of industrial worker struggles has passed with the deterioration of their employment base. Nonetheless, the hope for a labor movement, projected from afar, has followed factories to inland provinces, with academics and NGOs arguing that relocation might cause a “new wave of worker protests” closer to migrants’ homes that would mark some kind of qualitative advancement over the coastal struggles of the past two decades.[39] On the one hand, it is true that provinces like Guangdong are no longer the center of gravity for labor unrest.[40] So far, however, local research has found that inland factory struggles have mainly exhibited weak echoes of those on the coast.[41]

No Room for a Raise

If the post-Honda era has proven anything, it has been the growing “illegitimacy of the wage demand,”[42] rather than a renewed era of offensive trade unionism. Take, for example, the inability to provide legally mandated social insurance coverage to workers. Landmark labor legislation in the late 2000s and early 2010s was expected to stabilize wage relations and provide a social insurance scheme for China. In part, this was meant as a final replacement for the cradle-to-grave benefits of the “iron rice bowl” offered to state-owned enterprise workers that had been lost over decades of reform. At the same time, the goal was similar to state welfare policies in the high-income countries, intended to enforce a basic stability in the labor market by securing the reproduction of labor-power through maternity leave, pensions, medical benefits, etc. The Labor Contract Law of 2008 sought to guarantee a labor contract and shared employer-employee funded social insurance program for all workers, and the social insurance network was further clarified in the 2011 Social Insurance Law, which guaranteed “five insurances and one fund” to workers: a pension, unemployment, medical and work-related injury insurances were to be paired with the housing provident fund, which is meant to allow workers to save money toward buying a home, but is often used as a second pension. All of this was to be paid for by joint contributions from employer and employee at given rates set in slight variation according to local municipal regulations and paid into local government coffers.

Workers’ social insurance entitlements, however, are as a rule actively pushed aside by local officials and employers, who both know that enforcement would constrain, and in some cases decimate, profits. In fact, despite years of promotion of social insurance laws and efforts to build a more “social-democratic” state apparatus based on shared contributions from state, worker and employer, social insurance contribution adherence remains at abysmal lows. Moreover, benefits paid by migrant workers into local government accounts are notoriously difficult to transfer across administrative borders, or even to withdraw within the same province, causing many workers to ignore the system entirely. A government report from 2015 showed that only one third of the total workforce had a basic pension, while even fewer had basic medical insurance.[43] Things have not improved since. In January of 2018, the Ministry of Social Security revealed that migrant worker coverage of the various social insurance accounts ranged from 17 to 27 percent of China’s nearly 300 million migrant workers.

Tight profit margins restrict the capacity of enterprises to feasibly fulfill even the most basic material demands of workers, including their legally mandated social insurance commitments. Conditions in the Pearl River Delta city of Dongguan provide a good case study of the double bind that workers find themselves in. Dongguan, long a major hub in the “world’s factory,” has one of the highest concentrations of migrant workers in the country, and is also one of the few cities that has published government statistics on its migrant population, including the specific industries they work in, making it possible to approximate the total cost of unpaid social insurance both in a particular locality and across various industries. In 2015, the most recent data available, Dongguan had around four million migrant workers (probably a very conservative figure), 3.1 million of whom were in industrial manufacturing jobs.[44] Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security (MoHRSS) figures showed that, in the same year, out of the country’s 277 million migrant workers, only 20 percent had a basic pension, 19 percent had medical insurance, 27 percent had work accident insurance, and around 15 percent had unemployment insurance.[45] They provided no data on maternity insurance or the housing fund, but contributions for these funds is also exceptionally poor, if not lower, so an estimate of 20 percent for each of them would be optimistic.

Extrapolating from these figures, if manufacturers actually paid the social insurance contributions they still owed to Dongguan’s migrant factory workers in 2015, it would conservatively cost them at least 24 billion yuan.[46] According to government data, Dongguan’s “industrial” profits in enterprises over a certain size for 2015 was around 41 billion yuan, and this includes the construction industry, where average profit is likely higher. Nonetheless, such a massive payout would cut industrial profits in half. Paying workers a 35 percent wage increase alone, the percentage won by the Honda workers, would by itself cost 40 billion yuan across the industrial sector, effectively eliminating all profits. Adding unpaid social insurance at this new pay rate would hurl Dongguan firms deeply into the red, at a total cost of 76 billion yuan.

Modest increases in labor costs would be disastrous not only for China’s industrial core, but also for the brave new world of ecommerce, into which China’s elite have been investing a great deal of hope for a new wave of growth. Here we see fledgling industries move through what liberal economists call the “product cycle” at a breakneck pace: phases of expansion, homogenization and monopolization, followed ever more quickly by decline. Workers chase the relatively high wages of expansion, through stagnation, and then downward pressure on their pay and outright layoffs, followed by the search for another job—if one can be found at all. The dawn of China’s ecommerce “revolution” saw brands like Alibaba grow at incredible speed, though this “growth” simply chewed up and reconfigured older brick and mortar retail. The growth of online shops, and the associated industry of express parcel delivery, soaked up both unemployed college graduates and laid-off industrial workers in droves. During the phase of expansion, express delivery drivers—though predominantly men in an industry that almost universally excludes women—could make good money, taking home around 4,000 yuan per month on average in 2010[47] when the average industrial wage was around half as much.[48] Alibaba grew to a virtual monopoly in the market with an 80 percent market share by 2013.[49] In that year, the same that the total number of industrial workers reached its climax before declining, Premier Li Keqiang praised Alibaba’s CEO for “creating jobs” for countless drivers and online shop owners, and for “freeing” the productive power of the old economy.[50] However, these new industries have a bad habit of exhibiting many of the same problems as the old ones. For example, JD.com CEO Liu Qiangdong famously estimated that 90 percent of his company’s full-time drivers had social insurance, but like many others companies, JD relies heavily on outsourcing, independent contractors and part-time drivers.[51] When the express delivery industry became saturated, wages began to stagnate and eventually to fall, just as companies began dumping capital into a sea of different contenders in the rising food delivery industry. A study from 2016 showed that around half of delivery workers made between 2,000 and 4,000 yuan per month, with long hours and no social insurance.[52] Drivers soon began jumping ship to food delivery, where wages were twice as high.[53] But again wage growth eventually stalled and cuts began, just as the market became dominated by two major players: Meituan-Dianping and Ele.me.[54]

But the context here is important. These companies, and others in ecommerce, have been engaged for years in a nearly endless spending war, never turning a profit. Meituan-Dianping, now the largest food delivery company, has clawed its way to the top of the industry through years of losses, and has yet to turn a profit as of late 2018.[55] Stocks plummeted shortly after the company’s IPO as its losses continued to grow, leading to layoffs.[56] To place this in context: the company employs roughly 500,000 drivers.[57] And a major restructuring at JD.com in the same year saw the company finally move into the black after years of losses.[58] Many of these companies are simply riding another bubble, similar in character to the US tech bubble of the late 1990s, sustained by enormous sums of speculative investment funds that cannot be profitably poured into the productive economy. Instead, “unicorn” companies are buoyed by successive waves of venture capital, creating new monopoly-scale conglomerates that wield enormous power in the stock market—where they also funnel regular dividend payouts to shareholders—all in the expectation that their crucial market positions cannot help but result in profitable returns. This expectation, however, is a speculative gamble, and every stock market bust threatens to bring the whole edifice tumbling down.

The Proletariat and the Myth of the Middle

The conditions in Dongguan represent just one particularly manufacturing-heavy microcosm of macroeconomic dynamics in China as a whole. The country is now experiencing the simultaneous stagnation of GDP growth, slowing wage increases, and ballooning inequality between a rich population that is only growing more secure in its wealth and an increasingly vulnerable, informal and fractured working class. All of these trends are driven by the oversaturation of investment in productive industries, which in turn has forced the state to divert resources into large stimulus projects that only result in the accumulation of greater amounts of underperforming fixed capital in newly developed cities and industrial zones in the interior. These new developments tend to attract just a fraction of the productive investment they were intended for. In part, this is due to automation in places like Guangdong, which helps retain output and diminishes the need for new workers elsewhere. But, on the other hand, the labor costs of the interior are not as low as those in nearby coastal production hubs like Vietnam or Cambodia. On top of this, China’s vast interior simply has too many locales competing to absorb the industries priced out of the coast—even if a few succeed, the majority will be losers. Meanwhile, since all of these areas are under a single, unified currency, the effects of inflation move more readily across the national economy, and a strong yuan in the coast leads to a stronger yuan in the interior, despite wage differentials. On one hand, this does lead to capital spilling over into the development of other industries, including services. The growth of the service sector and a “consumer economy” is the official policy goal of the state. But this language obscures the real machinations of a capitalist economy.

It’s true that deindustrialization has already taken hold, growth rates across the country are beginning to slow and services are proliferating. But this is also taking place while wages are beginning to stagnate. In 2012, the year Xi Jinping came to power, China’s growth rate began dropping rapidly after a brief, stimulus-driven recovery following the crisis of 2008. By 2014, lower growth rates had been officially declared the “new normal,” with consumption-driven spending to be the new source of growth, rather than export-oriented manufacturing. This announcement was paired with the intentional closure of factories in cities like Beijing in an effort to drive down pollution and force industrial relocation to the less developed interior. At the time, it was imagined that new, consumer-oriented service industries would flood into the breach, helping to build a middle class and thereby catapult such cities into conditions resembling the imagined ideal of the high-income countries. In reality, this change simply put an even heavier strain on poorer workers (those who would soon be designated the “low-end population”) and further secured the gains of the hyper-rich.

The trajectory of struggles, as shown by Lu and Li’s data, is not trending in the direction of a labor movement, but is instead following these changes in class composition. Clinging to the image of the factory worker only obscures the real topography of proletarian conditions. As anywhere else, China’s proletariat consists of those who have nothing but their capacity to work for a wage to survive, while capitalists control means of production and live off income from capital. But it’s often impossible to cleanly divide individuals’ class positions in the fashion of sociologists, who often substitute proxies like income brackets or education for actual class. Class is a society-wide polarity that emanates from the process of production. Individuals will always have a messy relationship to this overall polarity, since even those who own factories and live off dividends likely also have a wage income, just as those who predominantly live off of the wage may also own some stocks.

Despite this, a sliver of stocks does not make someone, in part, a capitalist, just as a CEO’s wage does not make them, in part, a proletarian. A true “middle stratum” stretched between the two only exists among better-off managers and smallholders or in conditions of general social prosperity, in which some larger portion of mid-income wage-earners may also receive substantial returns on privately-held investments. Even this segment of the population is so internally differentiated that we speak of the “middle strata” rather than a single stratum, which might be mistaken for something like a “middle class” with some presumed homogeneity. In reality, these middle strata are simply people who could reasonably live off of the profits of their small business or investments without working themselves, their waged income simply a means to propel them into a higher income bracket—but beyond this, the actual conditions of life afforded by their investments are wildly different, as are their waged incomes.

What, then, of the much publicized growth of the Chinese “middle class?” China’s class structure has, in fact, changed rapidly, but not in the ways claimed by the state. If we examine this illusion of the middle class in detail, we instead find a slowly growing minority of extraordinarily wealthy individuals, a narrow upper stratum of affluent white-collar workers, and a vast majority who compose the increasingly diverse working class of white and blue collar workers, sitting just above the growing population of the unemployed and semi-employed. Within this majority, there exists substantial internal stratification, but it is important not to mistake this for the existence of an expansive, homogenous middle stratum. The same is true of widely publicized cases of rapid upward mobility: while the jump to affluence is probably more feasible for workers in China than in the US, for example, it is by no means a common occurrence. Insofar as we speak of the “middle strata,” then, it is important to note its extreme internal differentiation, as well as the simple fact that the bulk of the “middle strata” lies in its bottom rungs and is still effectively proletarian, though additional sources of income and managerial roles within production contribute to an ideological divergence that often does not match their material conditions.[59]

An in-depth study of income inequality since 1978 showed income distribution in China was among the most equal in the world in the late 1970s and is now among the most unequal, currently near the level of the United States.[60] In 2015, the bottom half of the population (over 500 million people) took just 14.8 percent of the annual national income, a per capita average of 17,150 yuan (around US $2,500) per year, while the top one percent possessed nearly the same amount, 13.9 percent of the national income, averaging 804,886 yuan ($117,000) per person per year. In terms of wealth, those with the most saw their wealth grow most rapidly since 1978, with the top one percent and top 0.01 percent growing the fastest, at 8.4 and 9.1 percent per year on average respectively. The wealth of the lowest half of the population grew at only around 4 percent per year over the same time period—slower than the economy as a whole, which grew at an average of 6.2 percent.[61] Even government figures confirm that the gap between the lower strata and the top has continued to widen at an alarming rate, particularly in rural areas. The disposable income of the lowest 20 percent of the rural population grew by just 3.5 percent per year on average between 2013 and 2017, while the highest 20 percent of rural households grew by 10 percent per year. These figures only emphasize that the rich continue to get richer—and at a faster rate—while the poorest remain locked into increasingly unchanging conditions, barely keeping ahead of inflation.

Middle Strata

Since inequality in China is today similar to that of the United States, it will be helpful to detour here into a brief comparison of the two countries’ class structures. This isn’t meant as a systematic study, but instead as an attempt to compare in broad strokes: Among the best existing attempts to quantify a Marxist definition of class for the population over time for the US is a detailed empirical study of income levels performed by Simon Mohun, who decomposes income into that gained from waged labor and that gained from other sources (i.e., capital income and rent).[62] Derived from tax data, these numbers certainly underestimate the lowest rungs of the proletariat, such as the growing homeless population, and the actual income levels of the highest rung of capitalists, who tend to make use of tax-free offshore accounts. Nonetheless, the general shape of the country’s class structure is clearly visible, and, perhaps surprisingly, the overall class distribution of the United States has changed little for nearly a century, despite radical changes in technology, employment and the basic geography of production.

According to Mohun’s calculations, those who are unambiguously capitalists, capable of surviving wholly off income from capital in the form of rent, dividends and interest, made up two percent of the (tax-paying) population in the US in 2011, while the working class accounted for eighty-four percent. Meanwhile, between the bulk of workers and the small fraction of capitalists lay a stratum of “managers,” defined as those who take at least some substantial portion of their income from capital, but still require their wage income (more specifically, they do not make at least the average workers’ wage from their non-wage income). There have been a few changes in the time period examined by Mohun, most of them slight. The share of capitalists shrank marginally (from 3.8% of tax-payers in 1918), as did the share of workers (from 88% in 1918). Making up the difference has been the oscillating growth of the wage-dependent managerial strata, which composed a larger share of the total in the years leading up to the Great Depression (6%-12% in the 1920s), then troughed in the 1940s at about four percent of taxpayers before rapidly and continuously ascending in the postwar period, peaking in the 1980s at about 19 percent before experiencing a moderate fall, accounting for about 14 percent of the population in 2011. The growth of this managerial grouping has clearly been related to changes in the structure of production, but also defies any simple association with “neoliberalism” or “globalization” since it spans both the early and later postwar periods, and was fairly high throughout the 1920s. If anything, more recent economic restructuring seems to be associated with only a moderate decline in managers since the early 1990s, as the lowest rungs of this strata were pushed back into the working class.

The Marxist understanding of the “middle strata” does not correlate directly with this managerial group, who might be understood as “upper-middle class” in everyday parlance. But the growth of this segment does reflect the disintegrating effect of technical changes on the proletariat more broadly. At the same time, the other substantial change noted in Mohun’s study has been the notable re-polarization of the class structure, particularly after the 1980s. The income of the definitively capitalist grouping has increased relative to both the managerial strata and the vast majority of those who subsist primarily on the wage. Managers’ wages have also increased relative to workers’, but this has been concurrent with the decline of the share of taxpayers in this category.[63] In general, inequality has grown to mirror and in some cases surpass the conditions that prevailed prior to the Great Depression. If we take a more expansive view of the “middle strata” to include non-managerial workers within higher income brackets, the current period is marked by fragmentation across the board: increasing general polarization is accompanied by the disintegration and polarization of the middle strata—fragmenting into even more substrata, which mostly orbit the bottom of the “middle class,” while the richest managers and technicians grow fewer and wealthier, even if they are still not quite capitalists. Coupled with the disintegration of the proletariat (its “unity in separation”), the picture is one of proliferating stratification in the midst of a more extreme economy-wide polarization.

It is difficult to say where exactly these same lines lie in China, but what seems clear is that the prophesied middle class is not in the process of forming as a coherent, stabilizing social force. Some hint of what is going on can be inferred from data on housing, since homeownership is usually the central category used in mainstream economics to define inclusion within a middle class, at least in the US. Viewed through this lens, we see a young Chinese proletariat largely divided into two large groups: roughly half scrape by in low paying jobs, renting for a living; the other half have higher wages and may even own a home, but only resemble the mythical middle class on the surface, since even these higher-income workers face stagnant wages, rising costs and crippling debt. This is in stark contrast with the popular idea of middle-class life, defined by secure homeownership, rising income and sufficient savings.